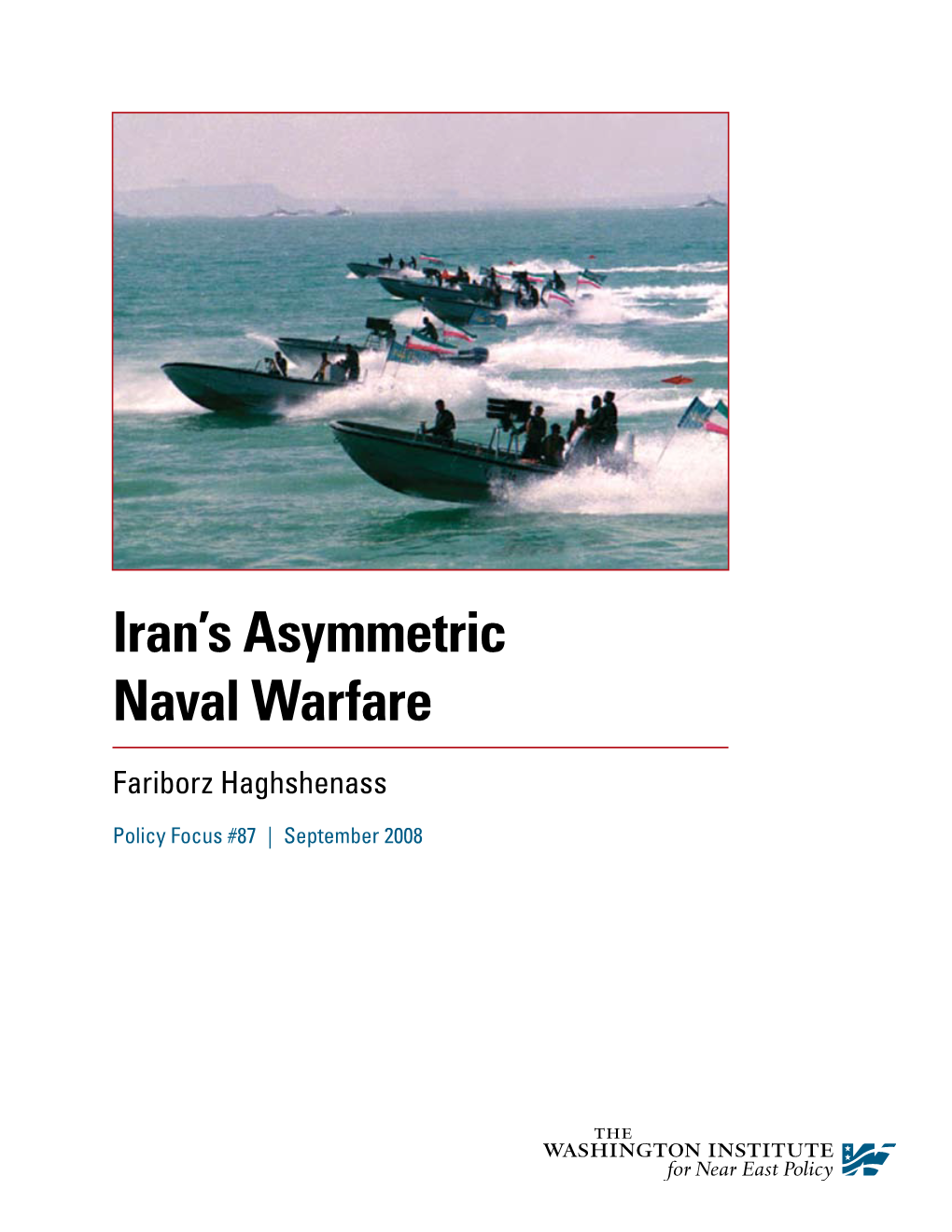

Iran's Asymmetric Naval Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Warfare in World War II

Coastal Warfare in World War II Christopher P. Carlson Cold Wars 2003 Admiralty Trilogy Seminar Introduction Coastal Warfare in WWII ♦ What is Coastal Warfare? ♦ Lioral/Coastal Environment ♦ Background ♦ Mighty Midgets - “Small Craft” ♦ Roles and Missions ♦ Tactics Overview ♦ National Development ♦ Post-WWII ♦ Coastal Warfare and CaS ♦ Some Good Books What is Coastal Warfare? Coastal Warfare in WWII ♦ “Lioral” or Coastal waters ♦ Shallow water, often sheltered waters • Sometimes too shallow for larger naval vessels ♦ Not seagoing ships • Can’t operate in Sea State 4-5, even then it’s unpleasant ♦ More than just PTs and other high-speed craft • Motor launches for minesweeping, ASW, rescue (e.g. British MLs) • Small minesweepers (e.g. German R-boats) • Barges for transporting cargo (e.g. Japanese Daihatsus) • Landing craft ♦ Common factor is small size • Limited endurance • Light armament • Low damage capacity !! Littoral/Coastal Environment Coastal Warfare in WWII ♦ Difficult environment due to the close proximity of land ♦ Detection Issue - Heavy clu1er ♦ Classification Issue - Many false contacts ♦ Reduced operation space - Restricted maneuverability ♦ All combine to reduce a ship’s reaction time Coastal waters Background Coastal Warfare in WWII ♦ WWI - These are distinct from the “Torpedo Boat” • Seagoing vessel intended for fleet action ♦ Who built coastal combatants? • Britain: Built a dozen Coastal Motor Boats (CMBs) ■ 40 ft long, single rearward launched torpedo & a few MGs ■ Several dozen motor launches, 76ft long, 3 pdr, general-purpose -

Iran Vies for More Influence in Iraq at a Budget Price by Farzin Nadimi

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3405 Iran Vies for More Influence in Iraq at a Budget Price by Farzin Nadimi Dec 3, 2020 Also available in Arabic / Farsi ABOUT THE AUTHORS Farzin Nadimi Farzin Nadimi, an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, is a Washington-based analyst specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Persian Gulf region. Brief Analysis Tehran aims to earn hard currency for its relatively cheap military hardware, ideally boosting its leverage in Baghdad at a fraction of the cost that the United States has been spending there. n November 14, a large Iraqi defense delegation began a four-day visit to Tehran as a follow-up to previous O exchanges with Iranian officials. The trip was led by Sunni defense minister Juma Saadoun al-Jubouri and included the commanders of each Iraqi military branch. According to Jubouri, its main goal was to “deepen” bilateral military and security cooperation. Three days later, the commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF), Brig. Gen. Esmail Qaani, reportedly paid a secret visit to Baghdad. These exchanges are all the more notable because they came after the UN ban on arms deals with Iran expired in October. Tehran is now free to market and sell its weapons abroad, and several potential customers have already shown interest—not just Iraq, but also Syria, Venezuela, and other players. To be sure, all of these governments are financially constrained, and the United States will likely continue disrupting such deals via existing secondary sanctions, most of them based on UN Security Council resolutions adopted between 2006 and 2015. -

Why China Has Not Caught Up

Why China Has Not Caught Up Yet Why China Has Not Andrea Gilli and Caught Up Yet Mauro Gilli Military-Technological Superiority and the Limits of Imitation, Reverse Engineering, and Cyber Espionage Can adversaries of the United States easily imitate its most advanced weapon systems and thus erode its military-technological superiority? Do reverse engineering, industrial espi- onage, and, in particular, cyber espionage facilitate and accelerate this process? China’s decades-long economic boom, military modernization program, mas- sive reliance on cyber espionage, and assertive foreign policy have made these questions increasingly salient. Yet, almost everything known about this topic draws from the past. As we explain in this article, the conclusions that the ex- isting literature has reached by studying prior eras have no applicability to the current day. Scholarship in international relations theory generally assumes that ris- ing states beneªt from the “advantage of backwardness,” as described by Andrea Gilli is a senior researcher at the NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) Defense College in Rome, Italy. Mauro Gilli is a senior researcher at the Center for Security Studies at the Swiss Federal Insti- tute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. The authors are listed in alphabetical order to reºect their equal contributions to this article. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of NATO, the NATO Defense College, or any other institution with which the authors are or have been -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES CSC 28 / CCEM 28 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES (MDS) THESIS THE CORVETTE - A SHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY CANADIAN NAVY LA CORVETTE - UN NAVIRE POUR LA MARINE CANADIENNE DU 21E SIÈCLE By/par LCdr/capc Pierre Bédard This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. The paper is a scholastic document, and thus L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au contains facts and opinions, which the author cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and correct for que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et the subject. -

King and Karabell BS

k o No. 3 • March 2008 o l Iran’s Global Ambition t By Michael Rubin u While the United States has focused its attention on Iranian activities in the greater Middle East, Iran has worked O assiduously to expand its influence in Latin America and Africa. Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s out- reach in both areas has been deliberate and generously funded. He has made significant strides in Latin America, helping to embolden the anti-American bloc of Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nicaragua. In Africa, he is forging strong n ties as well. The United States ignores these developments at its peril, and efforts need to be undertaken to reverse r Iran’s recent gains. e t Both before and after the Islamic Revolution, Iran Iranian officials have pursued a coordinated has aspired to be a regional power. Prior to 1979, diplomatic, economic, and military strategy to s Washington supported Tehran’s ambitions—after expand their influence in Latin America and a all, the shah provided a bulwark against both Africa. They have found success not only in communist and radical Arab nationalism. Follow- Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia, but also in E ing the Islamic Revolution, however, U.S. officials Senegal, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. These new viewed Iranian visions of grandeur warily. alliances will together challenge U.S. interests in e This wariness has grown as the Islamic Repub- these states and in the wider region, especially if l lic pursues nuclear technology in contravention Tehran pursues an inkblot strategy to expand its d to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty safe- influence to other regional states. -

The South China Sea and the Persian Gulf

Revista de Estudos Constitucionais, Hermenêutica e Teoria do Direito (RECHTD) 12(2):239-262, maio-agosto 2020 Unisinos - doi: 10.4013/rechtd.2020.122.05 A New Maritime Security Architecture for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: The South China Sea and the Persian Gulf Uma nova arquitetura de segurança marítima para a Rota da Seda Marítima do Século XXI: o Mar do Sul da China e o Golfo Pérsico Mohammad Ali Zohourian1 Xiamen University (China) [email protected] Resumo China e Irã possuem o antigo portão da Rota Marítima da Seda, além de duas novas vias nessa mesma rota, a saber, o Estreito de Ormuz e o Estreito de Malaca. Ao contrário do Estreito de Ormuz, a segurança marítima no Estreito de Malaca precisa ser redesenhada e restabelecida pelos Estados do litoral para o corredor de segurança. O objetivo deste estudo é descobrir o novo conceito e classificação de segurança marítima, notadamente os elementos de insegurança direta e indireta. Este estudo ilustra que os elementos diretos e indiretos mais notáveis são, respectivamente, pirataria, assalto à mão armada e presença de um Estado externo. Reconhece-se que a presença contínua e perigosa de um Estado externo é um elemento indireto de insegurança. À luz das atividades de violação e desestabilização por parte dos EUA no Golfo Pérsico e no Mar da China Meridional, sua presença e passagem são consideradas atividades não-inocentes, pois são prejudiciais à boa ordem, paz e segurança dos Estados localizados ao longo da costa. Portanto, uma nova proposta chamada Doutrina do “No Sheriff" é oferecida neste artigo para possivelmente impedir a formação de hegemonias em todas as regiões no futuro. -

High-Tech, Innovative Naval Solutions and Global Excellence

HIGH-TECH, INNOVATIVE NAVAL SOLUTIONS AND GLOBAL EXCELLENCE NAVAL PRODUCTS EXPERT AND INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS IN NAVAL SHIPBUILDING TAIS is established by the owners of the leading shipyards of Turkey with the objective to offer expert and innovative solutions in naval ship building for demanding customers all over the world. Located in the core of Turkey's shipbuilding industry in Tuzla and Yalova, TAIS partners have acquired a leading position by using the best know-how and state of art technologies and aspire to be among the world leaders in all segments that demand the advanced navy solutions. The group has completed a series of projects for Turkish Ministry of Defense for Turkish Navy which has achieved a contemporary, powerful and modern force structure. Besides shipbuilding TAIS offers a total solution of customer support and after-sales services at the start-up, deployment phases and through her entire life cycle. LET TAIS BE THE PARTNER FOR YOUR SUCCESS AND POWER! TURKISH NAVAL SHIPBUILDING KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERTISE WORKING TOGETHER Tuzla Tersaneler Caddesi No: 22 Tuzla Tersaneler Caddesi No: 14 Hersek Mah. İpekyolu Caddesi No:7 34944 Tuzla İstanbul Turkey 34940 Tuzla İstanbul Turkey 77700 Altinova Yalova Turkey Tel : 0216 446 61 14 Tel : 0216 581 77 00 Tel : 0226 815 36 36 Fax : 0216 446 60 82 Fax : 0216 581 77 01 Fax : 0226 815 36 37 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] TAIS OFFERS YOU A COMPLETE SET OF SOLUTIONS, KNOW-HOW AND EXPERTISE CONTRACTOR SHIP PROGRAMME MANAGEMENT • Program Management plans -

IRGC Navy Leadership Change May Not Signal Imminent Behavior Change | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3011 IRGC Navy Leadership Change May Not Signal Imminent Behavior Change by Farzin Nadimi Sep 5, 2018 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Farzin Nadimi Farzin Nadimi, an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, is a Washington-based analyst specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Persian Gulf region. Brief Analysis Despite the appointment of a radical anti-American commander, Iran’s naval forces are unlikely to resume frequent provocations without a strategic shift at the very top of the regime. n August 23, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei promoted the acting commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary O Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN), Alireza Tangsiri, to full commander, replacing Ali Fadavi, who was appointed as the wider IRGC’s deputy commander for coordination. In his appointment letter, Tangsiri was instructed to build an “agile and growing naval arm on par with [the demands of the] Islamic Republic” by carrying out three main objectives: making use of “religious manpower,” improving the navy’s “training, skills, intelligence dominance, and interoperability with other IRGC branches,” and “expanding its arsenal even further.” Yet his promotion does not necessarily signal a shift back to tense naval provocations in Persian Gulf waters, depending on how Khamenei decides to respond to forthcoming oil sanctions. WHO IS TANGSIRI? A naval brigade commander during the Iran-Iraq War, Tangsiri headed the IRGCN’s 1st Naval District in Bandar Abbas before becoming Fadavi’s deputy in 2010. He is known for his staunchly anti-American views and his vocal support for detaining Western naval personnel whose vessels stray into Iranian waters. -

Shipbuilding Industry 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Shipbuilding Industry Content

UKRINMASH SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY CONTENT 24 М15-V Marine Powerplant CONTENT М15-A Marine Powerplant 25 М35 Marine Powerplant М10/M16 Marine Powerplant 4 PROJECT 958 Amphibious Assault Hovercraft 26 UGT 3000R Gas-Turbine Engine KALKAN-МP Patrol Water-Jet Boat UGT 6000 Gas-Turbine Engine 5 GAYDUK-M Multipurpose Corvette 27 UGT 6000+ Gas-Turbine Engine GYURZA Armored River Gunboat UGT 15000 Gas-Turbine Engine 6 PROJECT 58130S Fast Patrol Boat 28 UGT 15000+ Gas-Turbine Engine CORAL Patrol Water-Jet Boat UGT 16000R Gas-Turbine Engine 7 BOBR Landing Craft/Military Transport 29 UGT 25000 Gas-Turbine Engine TRITON Landing Ship Tank 457KM Diesel Engine 8 BRIZ-40М Fast Patrol Boat 30 NAVAL AUTOMATED TACTICAL DATA SYSTEM BRIZ-40P Fast Coast Guard Boat MULTIBEAM ACTIVE ARRAY SURVEILLANCE RADAR STATION 9 PC655 Multipurpose Fast Corvette MUSSON Multipurpose Corvette 31 SENS-2 Optical Electronic System Of Gun Mount Fire Control 10 CARACAL Fast Attack Craft SAGA Optical Electronic System Of The Provision Corvette 58250 PROJECT Of Helicopter Take-Off, Homing And Ship Landing 11 GURZA-M Small Armored Boat 32 SARMAT Marine Optoelectronic Fire Control System Offshore Patrol Vessel DOZOR Of Small And Middle Artillery Caliber 12 KENTAVR Fast Assault Craft SONAR STATION MG – 361 (“CENTAUR”) PEARL-FAC Attack Craft-Missile 33 TRONKA-MK Hydroacoustic Station For Searching 13 NON-SELF-PROPELLED INTEGRATED SUPPORT VESSEL Of Saboteur Underwater Swimmers FOR COAST GUARD BOATS HYDROACOUSTIC STATION KONAN 750BR Fast Armored -

The Iranian Missile Challenge

The Iranian Missile Challenge By Anthony H. Cordesman Working Draft: June 4, 2019 Please provide comments to [email protected] SHAIGAN/AFP/Getty Images The Iranian Missile Challenge Anthony H. Cordesman There is no doubt that Iran and North Korea present serious security challenges to the U.S. and its strategic partners, and that their missile forces already present a major threat within their respective regions. It is, however, important to put this challenge in context. Both nations have reason to see the U.S. and America's strategic partners as threats, and reasons that go far beyond any strategic ambitions. Iran is only half this story, but its missile developments show all too clearly why both countries lack the ability to modernize their air forces, which has made them extremely dependent on missiles for both deterrence and war fighting. They also show that the missile threat goes far beyond the delivery of nuclear weapons, and is already becoming far more lethal and effective at a regional level. This analysis examines Iran's view of the threat, the problems in military modernization that have led to its focus on missile forces, the limits to its air capabilities, the developments in its missile forces, and the war fighting capabilities provided by its current missile forces, its ability to develop conventionally armed precision-strike forces, and its options for deploying nuclear-armed missiles. IRAN'S PERCEPTIONS OF THE THREAT ...................................................................................................... 2 IRAN'S INFERIORITY IN ARMS IMPORTS ................................................................................................... 3 THE AIR BALANCE OVERWHELMINGLY FAVORS THE OTHER SIDES ........................................................... 4 IRAN (AND NORTH KOREA'S) DEPENDENCE ON MISSILES ........................................................................ -

A Linguistic Analysis of Errors in News Agencies and Websites of Iran

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 5, No. 11, pp. 2340-2347, November 2015 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0511.19 A Linguistic Analysis of Errors in News Agencies and Websites of Iran Elham Akbari Department of General Linguistics, Shahroud Science and Researches Pardis, Iran Reza Kheirabadi Organization for Educational Research and Planning, Iran Abstract—In this research, we analyzed the common errors of three highly visited news websites of Iran within three syntactic, morphological and typographic-orthographic level to scrutinize the pitfalls of news websites. The data was gathered from three news websites of ALEF, ASRE-IRAN AND TABNAK which are listed among the most visited news websites in Iran based on Alexa ranking site. The findings showed that in studying the syntactic level of the materials on the news sites, one can face with a breach in the unmarked constituent order of Persian language and asymmetrical verbs deletion. Furthermore, the writing errors in the news are more of the typographical errors, and lack of using punctuations in the news and the commonest linguistic errors in morphological level in news sites are lexical redundancy Index Terms—errors, discourse, linguistic analysis, linguistic analysis of errors, news I. INTRODUCTION In new theories, “discourse” is a social and communicative act. In fact, discourse analysis is the analysis of the text in context. Text can be used in a broad sense by discourse analysis. Sometimes text can be news, a radio program, a page of the newspaper, a TV series, or a TV program, a simple talk, a social interaction and so on. -

WIFR Did Battleship Bismarck Try to Surrender?

WIFR OCT 2010 FRONT COVER _WIFR OCT 2010 FRONT COVER 15/09/2010 13:28 Page 1 INTERNATIONAL FLEET REVIEW www.warshipsifr.com UK DEFENCE REVIEW & THE RN SPECIAL DID BATTLESHIP BISMARCK TRY TO SURRENDER? CHINA RISES AS USA FALTERS? WHY THE October 2010 £3.95 AUSTRALIANS NEED A SSTTRROONNGG RRAANN DANISH FLEET REVIEW...PORTUGAL’S PIRACY WAR...NAVIES LOOK NORTH...PAKISTAN’S FLOODS writing, alters perspective, and is Lef t , main image: ‘The End of therefore potentially controversial. the Bismarck’ by leading UK maritime artist Paul Wright RSMA. Having found the surrender angle I © Paul Wright. asked myself what else had gone For further information e-mail: untold? [email protected] In looking at already published Lef t , inset : HMS Rodney’s accounts of the Bismarck Action I Tommy Byers, w ho saw signs t hat realised that, while they covered Bismarck sailors w ere t rying t o DID BATTLESHIP surrender. the final battle - some quite vividly - none of them, in my opinion, quite Photo: Byers Collection. conveyed the full horror. When Tommy Byers wrote to Baron von Müllenheim-Rechberg, the senior mind by the time they had been BISMARCK TRY TO surviving German officer, in the chased and harassed by the Royal early 1990s to ask if any Bismarck Navy for several days. On the day of survivors had seen signs of battle it only took 40 minutes, or surrender attempts aboard their less, to reduce Bismarck to a own ship, the Baron could not floating hell. It was understandable help. Nobody among those who that while some of the German could have revealed the truth had battleship’s crew fought on - being survived.