Historical Officers Report March 2019 Taken from Wikipedia in the Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commemorating the Overseas-Born Victoria Cross Heroes a First World War Centenary Event

Commemorating the overseas-born Victoria Cross heroes A First World War Centenary event National Memorial Arboretum 5 March 2015 Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, David Cameron The First World War saw unprecedented sacrifice that changed – and claimed – the lives of millions of people. Even during the darkest of days, Britain was not alone. Our soldiers stood shoulder-to-shoulder with allies from around the Commonwealth and beyond. Today’s event marks the extraordinary sacrifices made by 145 soldiers from around the globe who received the Victoria Cross in recognition of their remarkable valour and devotion to duty fighting with the British forces. These soldiers came from every corner of the globe and all walks of life but were bound together by their courage and determination. The laying of these memorial stones at the National Memorial Arboretum will create a lasting, peaceful and moving monument to these men, who were united in their valiant fight for liberty and civilization. Their sacrifice shall never be forgotten. Foreword Foreword Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles The Centenary of the First World War allows us an opportunity to reflect on and remember a generation which sacrificed so much. Men and boys went off to war for Britain and in every town and village across our country cenotaphs are testimony to the heavy price that so many paid for the freedoms we enjoy today. And Britain did not stand alone, millions came forward to be counted and volunteered from countries around the globe, some of which now make up the Commonwealth. These men fought for a country and a society which spanned continents and places that in many ways could not have been more different. -

Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2013–2014

EPORT 2013–2014 EPORT R L A L ANNU A ORI M R ME A N W A LI A AUSTR AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2013–2014 AUSTR A LI A N W A R ME M ORI A L ANNU A L R EPORT 2013–2014 EPORT AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2013–2014 Annual report for the year ended 30 June 2014, together with the financial statements and the report of the Auditor-General Images produced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra Cover: Their Royal Highness The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in a moment of private reflection at the Roll of Honour. PAIU2014/078.14 Title page: ANZAC Day National Ceremony 2014. PAIU2014/073.13 Copyright © Australian War Memorial ISSN 1441 4198 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. Australian War Memorial GPO Box 345 Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia www.awm.gov.au ii AUSTR A LI A N W A R ME M ORI A L ANNU A L R EPORT 2013–2014 EPORT Her Excellency the Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, on her final visit to the Australian War Memorial as Governor-General. His Excellency General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK MC (Retd), Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, and His Royal Highness The Duke of Cambridge KG KT during the Anzac Day National Ceremony 2014 commemorating the 99th anniversary of the Anzac landings. -

War Heritage Published by the Southern Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust November 2017 Springvale, Victoria, Australia 2017 1

The Rich War History of Springvale War Cemetery and Springvale Botanical Cemetery Victorian War Heritage Published by the Southern Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust November 2017 Springvale, Victoria, Australia 2017 1 The Southern Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust (SMCT) is a purposed, not-for- profit organisation that respects traditions, rites and rituals in relation to death, grief and mourning, and is honoured to be a custodian of significant cultural heritage for the Victorian Community. Caring for eight cemeteries and memorial parks within Melbourne, SMCT is committed to ensuring that the community is able to Honour and Celebrate the lives of not only those they have loved, but also those who have gone before us. SMCT’s Springvale Botanical Cemetery and the Springvale War Cemetery have a rich war graves history which will be shared through this publication with school children within the Springvale and Dandenong district and members of our community. It is through sharing the stories of the brave servicemen and service women resting peacefully at Springvale Botanical Cemetery and the Springvale War Cemetery that we begin to understand the significant sacrifices that were made for our country. We are grateful to the Victorian Veterans Council of the Department of Premier and Cabinet for funding this publication, which will encourage visitation and appreciation of Springvale Botanical Cemetery and the Springvale War Cemetery, precious community assets formed over time by our community’s rich cultural history. Jane Grover, CEO, Southern Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust 2 Introduction Victorian citizens have been involved in wars since the injury or illness. Some perished on home soil through nineteenth century and this booklet commemorates accidents and others struggled to survive back here the war service of so many individuals who participated in civilian life. -

The Report of the Inquiry Into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour

Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR This publication has been published by the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Copies of this publication are available on the Tribunal’s website: www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Editing and design by Biotext, Canberra. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR Senator The Hon. David Feeney Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Parliamentary Secretary, I am pleased to present the report of the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal’s Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour. The Inquiry was conducted in accordance with the Terms of Reference. The Tribunal that conducted the Inquiry arrived unanimously at the findings and recommendations set out in this report. In accordance with the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal Procedural Rules 2011, this report will be published on the Tribunal’s website — www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au — 20 working days after -

The Gallipoli Vcs, This Company of the Exhibition Will Contain the Memorial’S Complete Collection of Victoria Crosses from the Gallipoli Campaign

ICONS n March 20 the Australian War Memorial is launching a landmark travelling exhi- bition. For the first time ever, nine Victoria Crosses from its Ocollection will tour the country. Titled This company of brave men: the Gallipoli VCs, THIS COMPANY OF the exhibition will contain the Memorial’s complete collection of Victoria Crosses from the Gallipoli campaign. The tour is being held to mark the 95th anniversary of the Gallipoli campaign, and is made pos- sible through the generous sponsorship BRAVE MEN: of Mr Kerry Stokes AC and Seven Network Limited. The Victoria Cross is the highest form of recognition that can be bestowed on THE GALLIPOLI an Australian soldier for remarkable and unselfish courage in the service of others. It is a rare award, given when the nation Portrait of Captain Hugo Vivien Hope Throssell VC of the is at war, facing peril or a great test of na- 10th Australian Light Horse Regiment Australian War Memorial Director Steve Gower and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs Alan Griffin, tional commitment. All ranks of the serv- showing some of the Australian War Memorial’s collection of medals which include the Victoria Cross ices are eligible for the Victoria Cross. It is democratic in its nature and its distribu- tion reflects great integrity. The award has its origins in the mid-nineteenth century, when Queen Victoria instituted the medal Post, Gallipoli, on May 19, 1915. On that day in the early hours of the 29th. Throssell and as a special tribute to recognise acts of out- he and four other men were holding a por- his men became involved in a fierce bomb standing courage. -

Gerry Mccarthy Victoria Cross Medals in Darwin For

Gerry McCarthy MINISTER FOR ARTS & MUSEUMS 7 May 2010 Victoria Cross Medals In Darwin For The First Time Arts and Museums Minister Gerry McCarthy today viewed the complete set of Gallipoli Victoria Cross medals that are currently on display at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory. Mr McCarthy encouraged Territorians and tourists to view the medals which are part of the Australian War Memorial’s touring exhibition This company of brave men: the Gallipoli VCs . “The Victoria Cross is an integral part of Australia’s identity as a nation as it represents the remarkable acts of courage and sacrifice our soldiers have made in armed conflict,” Mr McCarthy said. “The battle at Gallipoli and the bravery of the ANZACs during World War I has united our nation to value unselfish courage in the service of others. “The nine Victoria Cross medals on display were awarded to soldiers who landed at Gallipoli in World War I, seven of which were awarded for bravery during the battle of Lone Pine.” The exhibition features the medals of: • Corporal Alexander Burton; • Corporal William Dunstan; • Private John Hamilton; • Lance Corporal Albert Jacka; • Lance Corporal Leonard Keysor; • Captain Alfred Shout; • Lieutenant William Symons; • Second Lieutenant Hugo Throssell; and • Lieutenant Frederick Tubb. “This is the first time these rare medals have been part of a national touring exhibition which provides people visiting MAGNT over the coming weeks with a valuable opportunity to learn about these ANZACs,” Mr McCarthy said. “I thank the Australian War Memorial and the generous support of Mr Kerry Stokes AC and the Seven Network Limited for making this unique exhibition possible. -

April 25Th, 2012

Walpole Weekly April 25th, 2012 Community News of Walpole, Nornalup, Peaceful Bay & Bow Bridge Proudly published in Litter Free Walpole Let us remember them ... Today is the anniversary of the Gallipoli landings, the day when we honour our fallen from all of the conflicts our nation has been involved in. We live in a country free to choose for ourselves what, when and where. A Nation where our rights as individuals are as important and as recognized as those of any organization be it private or government. We stand together as a nation proud of the sacrifices made by our forefathers and today ANZAC services held around the world acknowledge them. At 2.30 am on 25 April 1915, as the men of the Anzac Corps approached the west coast of Gallipoli in the ships of the invasion fleet, the Australian submarine AE2 entered the Dardanelles to disrupt Turkish sea communication. This is just one example of the heroism that happened that is not always acknowledged in the media. Many men died defending our way of life; for those who made it home to Australian soil (and New Zealand turf) their lives were never to be the same. Bearing the scars of war both physically and emotionally many never recovered from the horror and hardships they faced. Mates fought beside each other, brothers in arms heros to the generations that followed and yet many of these brave men themselves believe they just did their duty for their country. Victoria Crosses were hard earned. They stand out as official recognition of an act, or in some cases a series of acts, of outstanding courage. -

Brothers in Arms Enough Rope's

ENOUGH Rope’s GALLIPOLI: BROTHERS IN ARMS A STUDYGUIDE BY ROBERT LEWIS www.metromagazine.com.au www.theeducationshop.com.au OVERVIEW NOUGH ROPE’s Gallipoli: Brothers in Arms, (Andrew E Denton, 2007, 54 minutes) is the result of a visit by Andrew Denton to Gallipoli in 2006 for ANZAC Day, 25 April. The documentary uses historical footage and photographs, extracts from soldiers’ letters and diaries, and modern-day on-site interviews with Australian and Turkish experts, family members of ANZACs, and young backpackers. It explores two major ideas: FIONA GARDINER, ANDREW DENTON AND ALF GARDINER • What we can learn from the soldiers themselves about the • What Gallipoli means to Gallipoli in 2006, and through the experience of Gallipoli, using Australians today, explored occasional comments of Australian extracts from the letters of three through the memories, emotions pilgrims to the site. sets of brothers at Gallipoli in and values of relatives of those 1915; and three sets of men, present at CURRICULUM APPLICABILITY NOUGH ROPE’S Gallipoli: the war from the soldiers’ letters and of other evidence. Brothers in Arms is suitable diary entries) and page 12 (for the » Meanings of Gallipoli: Comparing E for use by students at middle- reactions and feelings of the modern the meanings and significance of upper secondary levels in Australian day visitors). Gallipoli for Australians over time. History and English. » Commemorating the event: Step 3 Then, when students have Comparing and analysing the ways In exploring the film, students need to finished watching the film, they can Gallipoli is commemorated on the focus on both the extracts from the work their way through the questions site and in Australia. -

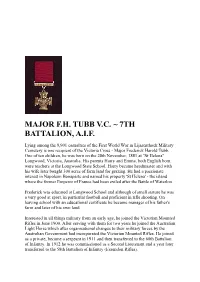

Major F.H. Tubb V.C. ~ 7Th Battalion, A.I.F

MAJOR F.H. TUBB V.C. ~ 7TH BATTALION, A.I.F. Lying among the 9,901 casualties of the First World War in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery is one recipient of the Victoria Cross - Major Frederick Harold Tubb. One of ten children, he was born on the 28th November, 1881 at "St Helena" Longwood, Victoria, Australia. His parents Harry and Emma, both English born were teachers at the Longwood State School. Harry became headmaster and with his wife later bought 300 acres of farm land for grazing. He had a passionate interest in Napoleon Bonaparte and named his property 'St Helena' - the island where the former Emperor of France had been exiled after the Battle of Waterloo. Frederick was educated at Longwood School and although of small stature he was a very good at sport, in particular football and proficient in rifle shooting. On leaving school with an educational certificate he became manager of his father's farm and later of his own land. Interested in all things military from an early age, he joined the Victorian Mounted Rifles in June 1900. After serving with them for two years he joined the Australian Light Horse which after organisational changes to their military forces by the Australian Government had incorporated the Victorian Mounted Rifles. He joined as a private, became a sergeant in 1911 and then transferred to the 60th Battalion of Infantry. In 1912 he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant and a year later transferred to the 58th Battalion of Infantry (Essendon Rifles). After the outbreak of the First World War he attested for overseas service with the Australian Imperial Force on the 12th August, 1914. -

Recipients of the Victoria Cross

Recipients of the Victoria Cross Recipients of the Victoria Cross The following 26 stories are about outstanding valour on the battlefields of the Great War. They tell the story of those men, either born or resident of Victoria, or who enlisted here, who were recipients of the Victoria Cross, the British Empire’s highest award for bravery in wartime, and now Australia’s pre-eminent award for conspicuous gallantry in combat. he award dates back to 1856 when it was instituted by Queen Not surprisingly most of the exploits occurred at Gallipoli and on TVictoria after the Crimean War and made retrospective to cover that the various battlefields of France; this includes the first Australian soldier conflict. It is an award that from the outset could be awarded to a soldier of the war to receive the Victoria Cross, Albert Jacka. of any rank, providing the action could be attested by witnesses and But other actions occurred in further fields. William Dartnell, born took place ‘in the face of the enemy’. in Collingwood in 1885 and buried in Kenya, was awarded his Victoria When hostilities broke out between the great powers of Europe Cross posthumously, after dying in September 1915 while fighting one hundred years ago, Australia had been a nation for only 14 years. against the German army in East Africa. The colony of Victoria had been established in 1851, only five years Samuel Pearse was born in Wales, migrated to Mildura, joined up before the introduction of the Victoria Cross, and the Queen had given when he was 17 and survived France, but received his posthumous her name to both. -

Record of Proceedings

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT Page Tuesday, 5 October 2010 ASSENT TO BILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3473 Tabled paper: Letter, dated 21 September 2010, from Her Excellency the Governor advising of assent to bills.......................................................................................................................................................... 3473 PRIVILEGE ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 3473 Comments by Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and Minister for Trade ................................................ 3473 Tabled paper: Annotated copy of register of interest of the Hon. Stephen Robertson MP..................................... 3473 Tabled paper: Annotated copy of register of interest of Mr Michael Wai-Man Choi MP......................................... 3473 Tabled paper: Copy of page 55 of the standing orders. ......................................................................................... 3473 PRIVILEGE .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

The SERVICEMAN

Official Magazine of WODEN VALLEY SUB-BRANCH R.S.L. The SERVICEMAN First Published in January 1962 WINTER EDITION AUGUST 2016 12 Metres underground and hand carved into the Sandstone inside the ‘Chambers of the Black Hand’ Opal mine in Lightning Ridge, NSW, along with hundreds of other carvings by local artist Ron Canlin. 1 CONTENTS Office Bearers 2015-16 Page 3 From the Editor’s Desk Page 4 From the President Page 5-6 Fall In & Invitation from ACT RSL Page 7 Message from the Prime Minister Page 8 Sub-Branch Annual Report 2015 Page 9-10 Vietnam Vets Events Program Page 11 Canberra Hospital ANZAC Service Page 12 Private Barry Francis Howarth Page 13 Seymour Baths Page 14 Chief Minister Award Ceremony Page 15-16 The Molonglo Mystery Page 17 Timor-Leste Veterans Page 18 Remembering Brigadier Bill Rolfe Page 19 2016 ANZAC & Peace Ceremony Page 20 Essay Competition 1st Place Page 23 “Last Post” and 2016 Poppy Appeal Page 24 Essay Competition 2nd Place Page 25 Essay Competitioin Equal 3rd Place Page 26 Essay Competition Equal 3rd Place Page 27 Gallipoli Rest Area - Holbrook NSW Page 28 World War I Nurses Project Page 29 ANZAC Eve Dinner Page 31 Eddson Day Club Report Page 32 Battle of the Somme & Words Page 33 A Tribute to Jan Szpunar Page 34 Bungendore Mental Health Forum Page 35 Leongatha - Avenue of Honour Page 37 Heidelberg Repat Hospital Page 38-39 Diary notes, Hospital Visiting Page 40 From a Dane to a Digger - Twice Page 41-42 ADVERTISERS RSL Money Page 21-22 Southern Cross Club Page 30 RSLSHOP Products Page 36 Legacy Badge Week Page 40 Grantley Perry & Sons Page 43 Note: Unless specifically stated otherwise, the experiences and opinions expressed in any article are those of the author and do not represent the official position of, or endorsement by the RSL, or by ‘The Serviceman’ as a journal.