Logic & Propositions: Chapter 3.1 –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Elementary Set Theory

1 Elementary Set Theory Notation: fg enclose a set. f1; 2; 3g = f3; 2; 2; 1; 3g because a set is not defined by order or multiplicity. f0; 2; 4;:::g = fxjx is an even natural numberg because two ways of writing a set are equivalent. ; is the empty set. x 2 A denotes x is an element of A. N = f0; 1; 2;:::g are the natural numbers. Z = f:::; −2; −1; 0; 1; 2;:::g are the integers. m Q = f n jm; n 2 Z and n 6= 0g are the rational numbers. R are the real numbers. Axiom 1.1. Axiom of Extensionality Let A; B be sets. If (8x)x 2 A iff x 2 B then A = B. Definition 1.1 (Subset). Let A; B be sets. Then A is a subset of B, written A ⊆ B iff (8x) if x 2 A then x 2 B. Theorem 1.1. If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A = B. Proof. Let x be arbitrary. Because A ⊆ B if x 2 A then x 2 B Because B ⊆ A if x 2 B then x 2 A Hence, x 2 A iff x 2 B, thus A = B. Definition 1.2 (Union). Let A; B be sets. The Union A [ B of A and B is defined by x 2 A [ B if x 2 A or x 2 B. Theorem 1.2. A [ (B [ C) = (A [ B) [ C Proof. Let x be arbitrary. x 2 A [ (B [ C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B [ C iff x 2 A or (x 2 B or x 2 C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B or x 2 C iff (x 2 A or x 2 B) or x 2 C iff x 2 A [ B or x 2 C iff x 2 (A [ B) [ C Definition 1.3 (Intersection). -

Propositional Logic, Modal Logic, Propo- Sitional Dynamic Logic and first-Order Logic

A I L Madhavan Mukund Chennai Mathematical Institute E-mail: [email protected] Abstract ese are lecture notes for an introductory course on logic aimed at graduate students in Com- puter Science. e notes cover techniques and results from propositional logic, modal logic, propo- sitional dynamic logic and first-order logic. e notes are based on a course taught to first year PhD students at SPIC Mathematical Institute, Madras, during August–December, . Contents Propositional Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Axiomatisations . . Maximal Consistent Sets and Completeness . . Compactness and Strong Completeness . Modal Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Correspondence eory . . Axiomatising valid formulas . . Bisimulations and expressiveness . . Decidability: Filtrations and the finite model property . . Labelled transition systems and multi-modal logic . Dynamic Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Axiomatising valid formulas . First-Order Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Formalisations in first-order logic . . Satisfiability: Henkin’s reduction to propositional logic . . Compactness and the L¨owenheim-Skolem eorem . . A Complete Axiomatisation . . Variants of the L¨owenheim-Skolem eorem . . Elementary Classes . . Elementarily Equivalent Structures . . An Algebraic Characterisation of Elementary Equivalence . . Decidability . Propositional Logic . Syntax P = f g We begin with a countably infinite set of atomic propositions p0, p1,... and two logical con- nectives : (read as not) and _ (read as or). e set Φ of formulas of propositional logic is the smallest set satisfying the following conditions: • Every atomic proposition p is a member of Φ. • If α is a member of Φ, so is (:α). • If α and β are members of Φ, so is (α _ β). We shall normally omit parentheses unless we need to explicitly clarify the structure of a formula. -

On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities †

mathematics Article On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities † Marija Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Jove Ili´ca154, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] † The conclusions given in this paper were partially presented at the European Summer Meetings of the Association for Symbolic Logic, Logic Colloquium 2012, held in Manchester on 12–18 July 2012. Abstract: We give some simple examples of applying some of the well-known elementary probability theory inequalities and properties in the field of logical argumentation. A probabilistic version of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule is as follows: if propositions A, B, C, A ! B, and B ! C have probabilities a, b, c, r, and s, respectively, then for probability p of A ! C, we have f (a, b, c, r, s) ≤ p ≤ g(a, b, c, r, s), for some functions f and g of given parameters. In this paper, after a short overview of known rules related to conjunction and disjunction, we proposed some probabilized forms of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule, with the best possible bounds for the probability of conclusion, covering simultaneously the probabilistic versions of both modus ponens and modus tollens rules, as already considered by Suppes, Hailperin, and Wagner. Keywords: inequality; probability logic; inference rule MSC: 03B48; 03B05; 60E15; 26D20; 60A05 1. Introduction The main part of probabilization of logical inference rules is defining the correspond- Citation: Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c,M. On ing best possible bounds for probabilities of propositions. Some of them, connected with Basic Probability Logic Inequalities. conjunction and disjunction, can be obtained immediately from the well-known Boole’s Mathematics 2021, 9, 1409. -

Propositional Logic - Basics

Outline Propositional Logic - Basics K. Subramani1 1Lane Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering West Virginia University 14 January and 16 January, 2013 Subramani Propositonal Logic Outline Outline 1 Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Subramani Propositonal Logic (i) The Law! (ii) Mathematics. (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. (Paradox). Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Motivation Why Logic? Subramani Propositonal Logic (ii) Mathematics. (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. (Paradox). Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Motivation Why Logic? (i) The Law! Subramani Propositonal Logic (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. (Paradox). Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Motivation Why Logic? (i) The Law! (ii) Mathematics. Subramani Propositonal Logic (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. -

Logic in Computer Science

P. Madhusudan Logic in Computer Science Rough course notes November 5, 2020 Draft. Copyright P. Madhusudan Contents 1 Logic over Structures: A Single Known Structure, Classes of Structures, and All Structures ................................... 1 1.1 Logic on a Fixed Known Structure . .1 1.2 Logic on a Fixed Class of Structures . .3 1.3 Logic on All Structures . .5 1.4 Logics over structures: Theories and Questions . .7 2 Propositional Logic ............................................. 11 2.1 Propositional Logic . 11 2.1.1 Syntax . 11 2.1.2 What does the above mean with ::=, etc? . 11 2.2 Some definitions and theorems . 14 2.3 Compactness Theorem . 15 2.4 Resolution . 18 3 Quantifier Elimination and Decidability .......................... 23 3.1 Quantifiier Elimination . 23 3.2 Dense Linear Orders without Endpoints . 24 3.3 Quantifier Elimination for rationals with addition: ¹Q, 0, 1, ¸, −, <, =º ......................................... 27 3.4 The Theory of Reals with Addition . 30 3.4.1 Aside: Axiomatizations . 30 3.4.2 Other theories that admit quantifier elimination . 31 4 Validity of FOL is undecidable and is r.e.-hard .................... 33 4.1 Validity of FOL is r.e.-hard . 34 4.2 Trakhtenbrot’s theorem: Validity of FOL over finite models is undecidable, and co-r.e. hard . 39 5 Quantifier-free theory of equality ................................ 43 5.1 Decidability using Bounded Models . 43 v vi Contents 5.2 An Algorithm for Conjunctive Formulas . 44 5.2.1 Computing ¹º ................................... 47 5.3 Axioms for The Theory of Equality . 49 6 Completeness Theorem: FO Validity is r.e. ........................ 53 6.1 Prenex Normal Form . -

Propositional Logic (PDF)

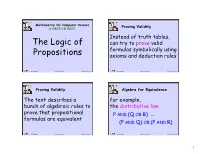

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

Sets, Propositional Logic, Predicates, and Quantifiers

COMP 182 Algorithmic Thinking Sets, Propositional Logic, Luay Nakhleh Computer Science Predicates, and Quantifiers Rice University !1 Reading Material ❖ Chapter 1, Sections 1, 4, 5 ❖ Chapter 2, Sections 1, 2 !2 ❖ Mathematics is about statements that are either true or false. ❖ Such statements are called propositions. ❖ We use logic to describe them, and proof techniques to prove whether they are true or false. !3 Propositions ❖ 5>7 ❖ The square root of 2 is irrational. ❖ A graph is bipartite if and only if it doesn’t have a cycle of odd length. ❖ For n>1, the sum of the numbers 1,2,3,…,n is n2. !4 Propositions? ❖ E=mc2 ❖ The sun rises from the East every day. ❖ All species on Earth evolved from a common ancestor. ❖ God does not exist. ❖ Everyone eventually dies. !5 ❖ And some of you might already be wondering: “If I wanted to study mathematics, I would have majored in Math. I came here to study computer science.” !6 ❖ Computer Science is mathematics, but we almost exclusively focus on aspects of mathematics that relate to computation (that can be implemented in software and/or hardware). !7 ❖Logic is the language of computer science and, mathematics is the computer scientist’s most essential toolbox. !8 Examples of “CS-relevant” Math ❖ Algorithm A correctly solves problem P. ❖ Algorithm A has a worst-case running time of O(n3). ❖ Problem P has no solution. ❖ Using comparison between two elements as the basic operation, we cannot sort a list of n elements in less than O(n log n) time. ❖ Problem A is NP-Complete. -

CS245 Logic and Computation

CS245 Logic and Computation Alice Gao December 9, 2019 Contents 1 Propositional Logic 3 1.1 Translations .................................... 3 1.2 Structural Induction ............................... 8 1.2.1 A template for structural induction on well-formed propositional for- mulas ................................... 8 1.3 The Semantics of an Implication ........................ 12 1.4 Tautology, Contradiction, and Satisfiable but Not a Tautology ........ 13 1.5 Logical Equivalence ................................ 14 1.6 Analyzing Conditional Code ........................... 16 1.7 Circuit Design ................................... 17 1.8 Tautological Consequence ............................ 18 1.9 Formal Deduction ................................. 21 1.9.1 Rules of Formal Deduction ........................ 21 1.9.2 Format of a Formal Deduction Proof .................. 23 1.9.3 Strategies for writing a formal deduction proof ............ 23 1.9.4 And elimination and introduction .................... 25 1.9.5 Implication introduction and elimination ................ 26 1.9.6 Or introduction and elimination ..................... 28 1.9.7 Negation introduction and elimination ................. 30 1.9.8 Putting them together! .......................... 33 1.9.9 Putting them together: Additional exercises .............. 37 1.9.10 Other problems .............................. 38 1.10 Soundness and Completeness of Formal Deduction ............... 39 1.10.1 The soundness of inference rules ..................... 39 1.10.2 Soundness and Completeness -

From Fuzzy Sets to Crisp Truth Tables1 Charles C. Ragin

From Fuzzy Sets to Crisp Truth Tables1 Charles C. Ragin Department of Sociology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721 USA [email protected] Version: April 2005 1. Overview One limitation of the truth table approach is that it is designed for causal conditions are simple presence/absence dichotomies (i.e., Boolean or "crisp" sets). Many of the causal conditions that interest social scientists, however, vary by level or degree. For example, while it is clear that some countries are democracies and some are not, there are many in-between cases. These countries are not fully in the set of democracies, nor are they fully excluded from this set. Fortunately, there is a well-developed mathematical system for addressing partial membership in sets, fuzzy-set theory. Section 2 of this paper provides a brief introduction to the fuzzy-set approach, building on Ragin (2000). Fuzzy sets are especially powerful because they allow researchers to calibrate partial membership in sets using values in the interval between 0 (nonmembership) and 1 (full membership) without abandoning core set theoretic principles, for example, the subset relation. Ragin (2000) demonstrates that the subset relation is central to the analysis of multiple conjunctural causation, where several different combinations of conditions are sufficient for the same outcome. While fuzzy sets solve the problem of trying to force-fit cases into one of two categories (membership versus nonmembership in a set), they are not well suited for conventional truth table analysis. With fuzzy sets, there is no simple way to sort cases according to the combinations of causal conditions they display because each case's array of membership scores may be unique. -

12 Propositional Logic

CHAPTER 12 ✦ ✦ ✦ ✦ Propositional Logic In this chapter, we introduce propositional logic, an algebra whose original purpose, dating back to Aristotle, was to model reasoning. In more recent times, this algebra, like many algebras, has proved useful as a design tool. For example, Chapter 13 shows how propositional logic can be used in computer circuit design. A third use of logic is as a data model for programming languages and systems, such as the language Prolog. Many systems for reasoning by computer, including theorem provers, program verifiers, and applications in the field of artificial intelligence, have been implemented in logic-based programming languages. These languages generally use “predicate logic,” a more powerful form of logic that extends the capabilities of propositional logic. We shall meet predicate logic in Chapter 14. ✦ ✦ ✦ ✦ 12.1 What This Chapter Is About Section 12.2 gives an intuitive explanation of what propositional logic is, and why it is useful. The next section, 12,3, introduces an algebra for logical expressions with Boolean-valued operands and with logical operators such as AND, OR, and NOT that Boolean algebra operate on Boolean (true/false) values. This algebra is often called Boolean algebra after George Boole, the logician who first framed logic as an algebra. We then learn the following ideas. ✦ Truth tables are a useful way to represent the meaning of an expression in logic (Section 12.4). ✦ We can convert a truth table to a logical expression for the same logical function (Section 12.5). ✦ The Karnaugh map is a useful tabular technique for simplifying logical expres- sions (Section 12.6). -

Logic, Proofs

CHAPTER 1 Logic, Proofs 1.1. Propositions A proposition is a declarative sentence that is either true or false (but not both). For instance, the following are propositions: “Paris is in France” (true), “London is in Denmark” (false), “2 < 4” (true), “4 = 7 (false)”. However the following are not propositions: “what is your name?” (this is a question), “do your homework” (this is a command), “this sentence is false” (neither true nor false), “x is an even number” (it depends on what x represents), “Socrates” (it is not even a sentence). The truth or falsehood of a proposition is called its truth value. 1.1.1. Connectives, Truth Tables. Connectives are used for making compound propositions. The main ones are the following (p and q represent given propositions): Name Represented Meaning Negation p “not p” Conjunction p¬ q “p and q” Disjunction p ∧ q “p or q (or both)” Exclusive Or p ∨ q “either p or q, but not both” Implication p ⊕ q “if p then q” Biconditional p → q “p if and only if q” ↔ The truth value of a compound proposition depends only on the value of its components. Writing F for “false” and T for “true”, we can summarize the meaning of the connectives in the following way: 6 1.1. PROPOSITIONS 7 p q p p q p q p q p q p q T T ¬F T∧ T∨ ⊕F →T ↔T T F F F T T F F F T T F T T T F F F T F F F T T Note that represents a non-exclusive or, i.e., p q is true when any of p, q is true∨ and also when both are true. -

Logic, Sets, and Proofs David A

Logic, Sets, and Proofs David A. Cox and Catherine C. McGeoch Amherst College 1 Logic Logical Statements. A logical statement is a mathematical statement that is either true or false. Here we denote logical statements with capital letters A; B. Logical statements be combined to form new logical statements as follows: Name Notation Conjunction A and B Disjunction A or B Negation not A :A Implication A implies B if A, then B A ) B Equivalence A if and only if B A , B Here are some examples of conjunction, disjunction and negation: x > 1 and x < 3: This is true when x is in the open interval (1; 3). x > 1 or x < 3: This is true for all real numbers x. :(x > 1): This is the same as x ≤ 1. Here are two logical statements that are true: x > 4 ) x > 2. x2 = 1 , (x = 1 or x = −1). Note that \x = 1 or x = −1" is usually written x = ±1. Converses, Contrapositives, and Tautologies. We begin with converses and contrapositives: • The converse of \A implies B" is \B implies A". • The contrapositive of \A implies B" is \:B implies :A" Thus the statement \x > 4 ) x > 2" has: • Converse: x > 2 ) x > 4. • Contrapositive: x ≤ 2 ) x ≤ 4. 1 Some logical statements are guaranteed to always be true. These are tautologies. Here are two tautologies that involve converses and contrapositives: • (A if and only if B) , ((A implies B) and (B implies A)). In other words, A and B are equivalent exactly when both A ) B and its converse are true.