Logic, Proofs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialetheists' Lies About the Liar

PRINCIPIA 22(1): 59–85 (2018) doi: 10.5007/1808-1711.2018v22n1p59 Published by NEL — Epistemology and Logic Research Group, Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), Brazil. DIALETHEISTS’LIES ABOUT THE LIAR JONAS R. BECKER ARENHART Departamento de Filosofia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, BRAZIL [email protected] EDERSON SAFRA MELO Departamento de Filosofia, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, BRAZIL [email protected] Abstract. Liar-like paradoxes are typically arguments that, by using very intuitive resources of natural language, end up in contradiction. Consistent solutions to those paradoxes usually have difficulties either because they restrict the expressive power of the language, orelse because they fall prey to extended versions of the paradox. Dialetheists, like Graham Priest, propose that we should take the Liar at face value and accept the contradictory conclusion as true. A logical treatment of such contradictions is also put forward, with the Logic of Para- dox (LP), which should account for the manifestations of the Liar. In this paper we shall argue that such a formal approach, as advanced by Priest, is unsatisfactory. In order to make contradictions acceptable, Priest has to distinguish between two kinds of contradictions, in- ternal and external, corresponding, respectively, to the conclusions of the simple and of the extended Liar. Given that, we argue that while the natural interpretation of LP was intended to account for true and false sentences, dealing with internal contradictions, it lacks the re- sources to tame external contradictions. Also, the negation sign of LP is unable to represent internal contradictions adequately, precisely because of its allowance of sentences that may be true and false. -

1 Elementary Set Theory

1 Elementary Set Theory Notation: fg enclose a set. f1; 2; 3g = f3; 2; 2; 1; 3g because a set is not defined by order or multiplicity. f0; 2; 4;:::g = fxjx is an even natural numberg because two ways of writing a set are equivalent. ; is the empty set. x 2 A denotes x is an element of A. N = f0; 1; 2;:::g are the natural numbers. Z = f:::; −2; −1; 0; 1; 2;:::g are the integers. m Q = f n jm; n 2 Z and n 6= 0g are the rational numbers. R are the real numbers. Axiom 1.1. Axiom of Extensionality Let A; B be sets. If (8x)x 2 A iff x 2 B then A = B. Definition 1.1 (Subset). Let A; B be sets. Then A is a subset of B, written A ⊆ B iff (8x) if x 2 A then x 2 B. Theorem 1.1. If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A = B. Proof. Let x be arbitrary. Because A ⊆ B if x 2 A then x 2 B Because B ⊆ A if x 2 B then x 2 A Hence, x 2 A iff x 2 B, thus A = B. Definition 1.2 (Union). Let A; B be sets. The Union A [ B of A and B is defined by x 2 A [ B if x 2 A or x 2 B. Theorem 1.2. A [ (B [ C) = (A [ B) [ C Proof. Let x be arbitrary. x 2 A [ (B [ C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B [ C iff x 2 A or (x 2 B or x 2 C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B or x 2 C iff (x 2 A or x 2 B) or x 2 C iff x 2 A [ B or x 2 C iff x 2 (A [ B) [ C Definition 1.3 (Intersection). -

Chapter 5: Methods of Proof for Boolean Logic

Chapter 5: Methods of Proof for Boolean Logic § 5.1 Valid inference steps Conjunction elimination Sometimes called simplification. From a conjunction, infer any of the conjuncts. • From P ∧ Q, infer P (or infer Q). Conjunction introduction Sometimes called conjunction. From a pair of sentences, infer their conjunction. • From P and Q, infer P ∧ Q. § 5.2 Proof by cases This is another valid inference step (it will form the rule of disjunction elimination in our formal deductive system and in Fitch), but it is also a powerful proof strategy. In a proof by cases, one begins with a disjunction (as a premise, or as an intermediate conclusion already proved). One then shows that a certain consequence may be deduced from each of the disjuncts taken separately. One concludes that that same sentence is a consequence of the entire disjunction. • From P ∨ Q, and from the fact that S follows from P and S also follows from Q, infer S. The general proof strategy looks like this: if you have a disjunction, then you know that at least one of the disjuncts is true—you just don’t know which one. So you consider the individual “cases” (i.e., disjuncts), one at a time. You assume the first disjunct, and then derive your conclusion from it. You repeat this process for each disjunct. So it doesn’t matter which disjunct is true—you get the same conclusion in any case. Hence you may infer that it follows from the entire disjunction. In practice, this method of proof requires the use of “subproofs”—we will take these up in the next chapter when we look at formal proofs. -

In Defence of Constructive Empiricism: Metaphysics Versus Science

To appear in Journal for General Philosophy of Science (2004) In Defence of Constructive Empiricism: Metaphysics versus Science F.A. Muller Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Mathematics Utrecht University, P.O. Box 80.000 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] August 2003 Summary Over the past years, in books and journals (this journal included), N. Maxwell launched a ferocious attack on B.C. van Fraassen's view of science called Con- structive Empiricism (CE). This attack has been totally ignored. Must we con- clude from this silence that no defence is possible against the attack and that a fortiori Maxwell has buried CE once and for all, or is the attack too obviously flawed as not to merit exposure? We believe that neither is the case and hope that a careful dissection of Maxwell's reasoning will make this clear. This dis- section includes an analysis of Maxwell's `aberrance-argument' (omnipresent in his many writings) for the contentious claim that science implicitly and per- manently accepts a substantial, metaphysical thesis about the universe. This claim generally has been ignored too, for more than a quarter of a century. Our con- clusions will be that, first, Maxwell's attacks on CE can be beaten off; secondly, his `aberrance-arguments' do not establish what Maxwell believes they estab- lish; but, thirdly, we can draw a number of valuable lessons from these attacks about the nature of science and of the libertarian nature of CE. Table of Contents on other side −! Contents 1 Exordium: What is Maxwell's Argument? 1 2 Does Science Implicitly Accept Metaphysics? 3 2.1 Aberrant Theories . -

CSE Yet, Please Do Well! Logical Connectives

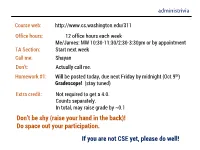

administrivia Course web: http://www.cs.washington.edu/311 Office hours: 12 office hours each week Me/James: MW 10:30-11:30/2:30-3:30pm or by appointment TA Section: Start next week Call me: Shayan Don’t: Actually call me. Homework #1: Will be posted today, due next Friday by midnight (Oct 9th) Gradescope! (stay tuned) Extra credit: Not required to get a 4.0. Counts separately. In total, may raise grade by ~0.1 Don’t be shy (raise your hand in the back)! Do space out your participation. If you are not CSE yet, please do well! logical connectives p q p q p p T T T T F T F F F T F T F NOT F F F AND p q p q p q p q T T T T T F T F T T F T F T T F T T F F F F F F OR XOR 푝 → 푞 • “If p, then q” is a promise: p q p q F F T • Whenever p is true, then q is true F T T • Ask “has the promise been broken” T F F T T T If it’s raining, then I have my umbrella. related implications • Implication: p q • Converse: q p • Contrapositive: q p • Inverse: p q How do these relate to each other? How to see this? 푝 ↔ 푞 • p iff q • p is equivalent to q • p implies q and q implies p p q p q Let’s think about fruits A fruit is an apple only if it is either red or green and a fruit is not red and green. -

Conditional Statement/Implication Converse and Contrapositive

Conditional Statement/Implication CSCI 1900 Discrete Structures •"ifp then q" • Denoted p ⇒ q – p is called the antecedent or hypothesis Conditional Statements – q is called the consequent or conclusion Reading: Kolman, Section 2.2 • Example: – p: I am hungry q: I will eat – p: It is snowing q: 3+5 = 8 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 1 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 2 Conditional Statement/Implication Truth Table Representing Implication (continued) • In English, we would assume a cause- • If viewed as a logic operation, p ⇒ q can only be and-effect relationship, i.e., the fact that p evaluated as false if p is true and q is false is true would force q to be true. • This does not say that p causes q • If “it is snowing,” then “3+5=8” is • Truth table meaningless in this regard since p has no p q p ⇒ q effect at all on q T T T • At this point it may be easiest to view the T F F operator “⇒” as a logic operationsimilar to F T T AND or OR (conjunction or disjunction). F F T CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 3 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 4 Examples where p ⇒ q is viewed Converse and contrapositive as a logic operation •Ifp is false, then any q supports p ⇒ q is • The converse of p ⇒ q is the implication true. that q ⇒ p – False ⇒ True = True • The contrapositive of p ⇒ q is the –False⇒ False = True implication that ~q ⇒ ~p • If “2+2=5” then “I am the king of England” is true CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 5 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 6 1 Converse and Contrapositive Equivalence or biconditional Example Example: What is the converse and •Ifp and q are statements, the compound contrapositive of p: "it is raining" and q: I statement p if and only if q is called an get wet? equivalence or biconditional – Implication: If it is raining, then I get wet. -

Automated Unbounded Verification of Stateful Cryptographic Protocols

Automated Unbounded Verification of Stateful Cryptographic Protocols with Exclusive OR Jannik Dreier Lucca Hirschi Sasaˇ Radomirovic´ Ralf Sasse Universite´ de Lorraine Department of School of Department of CNRS, Inria, LORIA Computer Science Science and Engineering Computer Science F-54000 Nancy ETH Zurich University of Dundee ETH Zurich France Switzerland UK Switzerland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Exclusive-or (XOR) operations are common in cryp- on widening the scope of automated protocol verification tographic protocols, in particular in RFID protocols and elec- by extending the class of properties that can be verified to tronic payment protocols. Although there are numerous appli- include, e.g., equivalence properties [19], [24], [27], [51], cations, due to the inherent complexity of faithful models of XOR, there is only limited tool support for the verification of [14], extending the adversary model with complex forms of cryptographic protocols using XOR. compromise [13], or extending the expressiveness of protocols, The TAMARIN prover is a state-of-the-art verification tool e.g., by allowing different sessions to update a global, mutable for cryptographic protocols in the symbolic model. In this state [6], [43]. paper, we improve the underlying theory and the tool to deal with an equational theory modeling XOR operations. The XOR Perhaps most significant is the support for user-specified theory can be freely combined with all equational theories equational theories allowing for the modeling of particular previously supported, including user-defined equational theories. cryptographic primitives [21], [37], [48], [24], [35]. -

Boolean Satisfiability Solvers: Techniques and Extensions

Boolean Satisfiability Solvers: Techniques and Extensions Georg WEISSENBACHER a and Sharad MALIK a a Princeton University Abstract. Contemporary satisfiability solvers are the corner-stone of many suc- cessful applications in domains such as automated verification and artificial intelli- gence. The impressive advances of SAT solvers, achieved by clever engineering and sophisticated algorithms, enable us to tackle Boolean Satisfiability (SAT) problem instances with millions of variables – which was previously conceived as a hope- less problem. We provide an introduction to contemporary SAT-solving algorithms, covering the fundamental techniques that made this revolution possible. Further, we present a number of extensions of the SAT problem, such as the enumeration of all satisfying assignments (ALL-SAT) and determining the maximum number of clauses that can be satisfied by an assignment (MAX-SAT). We demonstrate how SAT solvers can be leveraged to solve these problems. We conclude the chapter with an overview of applications of SAT solvers and their extensions in automated verification. Keywords. Satisfiability solving, Propositional logic, Automated decision procedures 1. Introduction Boolean Satisfibility (SAT) is the problem of checking if a propositional logic formula can ever evaluate to true. This problem has long enjoyed a special status in computer science. On the theoretical side, it was the first problem to be classified as being NP- complete. NP-complete problems are notorious for being hard to solve; in particular, in the worst case, the computation time of any known solution for a problem in this class increases exponentially with the size of the problem instance. On the practical side, SAT manifests itself in several important application domains such as the design and verification of hardware and software systems, as well as applications in artificial intelligence. -

CS 50010 Module 1

CS 50010 Module 1 Ben Harsha Apr 12, 2017 Course details ● Course is split into 2 modules ○ Module 1 (this one): Covers basic data structures and algorithms, along with math review. ○ Module 2: Probability, Statistics, Crypto ● Goal for module 1: Review basics needed for CS and specifically Information Security ○ Review topics you may not have seen in awhile ○ Cover relevant topics you may not have seen before IMPORTANT This course cannot be used on a plan of study except for the IS Professional Masters program Administrative details ● Office: HAAS G60 ● Office Hours: 1:00-2:00pm in my office ○ Can also email for an appointment, I’ll be in there often ● Course website ○ cs.purdue.edu/homes/bharsha/cs50010.html ○ Contains syllabus, homeworks, and projects Grading ● Module 1 and module are each 50% of the grade for CS 50010 ● Module 1 ○ 55% final ○ 20% projects ○ 20% assignments ○ 5% participation Boolean Logic ● Variables/Symbols: Can only be used to represent 1 or 0 ● Operations: ○ Negation ○ Conjunction (AND) ○ Disjunction (OR) ○ Exclusive or (XOR) ○ Implication ○ Double Implication ● Truth Tables: Can be defined for all of these functions Operations ● Negation (¬p, p, pC, not p) - inverts the symbol. 1 becomes 0, 0 becomes 1 ● Conjunction (p ∧ q, p && q, p and q) - true when both p and q are true. False otherwise ● Disjunction (p v q, p || q, p or q) - True if at least one of p or q is true ● Exclusive Or (p xor q, p ⊻ q, p ⊕ q) - True if exactly one of p or q is true ● Implication (p → q) - True if p is false or q is true (q v ¬p) ● -

Logical Connectives Good Problems: March 25, 2008

Logical Connectives Good Problems: March 25, 2008 Mathematics has its own language. As with any language, effective communication depends on logically connecting components. Even the simplest “real” mathematical problems require at least a small amount of reasoning, so it is very important that you develop a feeling for formal (mathematical) logic. Consider, for example, the two sentences “There are 10 people waiting for the bus” and “The bus is late.” What, if anything, is the logical connection between these two sentences? Does one logically imply the other? Similarly, the two mathematical statements “r2 + r − 2 = 0” and “r = 1 or r = −2” need to be connected, otherwise they are merely two random statements that convey no useful information. Warning: when mathematicians talk about implication, it means that one thing must be true as a consequence of another; not that it can be true, or might be true sometimes. Words and symbols that tie statements together logically are called logical connectives. They allow you to communicate the reasoning that has led you to your conclusion. Possibly the most important of these is implication — the idea that the next statement is a logical consequence of the previous one. This concept can be conveyed by the use of words such as: therefore, hence, and so, thus, since, if . then . , this implies, etc. In the middle of mathematical calculations, we can represent these by the implication symbol (⇒). For example 3 − x x + 7y2 = 3 ⇒ y = ± ; (1) r 7 x ∈ (0, ∞) ⇒ cos(x) ∈ [−1, 1]. (2) Converse Note that “statement A ⇒ statement B” does not necessarily mean that the logical converse — “statement B ⇒ statement A” — is also true. -

Deduction (I) Tautologies, Contradictions And

D (I) T, & L L October , Tautologies, contradictions and contingencies Consider the truth table of the following formula: p (p ∨ p) () If you look at the final column, you will notice that the truth value of the whole formula depends on the way a truth value is assigned to p: the whole formula is true if p is true and false if p is false. Contrast the truth table of (p ∨ p) in () with the truth table of (p ∨ ¬p) below: p ¬p (p ∨ ¬p) () If you look at the final column, you will notice that the truth value of the whole formula does not depend on the way a truth value is assigned to p. The formula is always true because of the meaning of the connectives. Finally, consider the truth table table of (p ∧ ¬p): p ¬p (p ∧ ¬p) () This time the formula is always false no matter what truth value p has. Tautology A statement is called a tautology if the final column in its truth table contains only ’s. Contradiction A statement is called a contradiction if the final column in its truth table contains only ’s. Contingency A statement is called a contingency or contingent if the final column in its truth table contains both ’s and ’s. Let’s consider some examples from the book. Can you figure out which of the following sentences are tautologies, which are contradictions and which contingencies? Hint: the answer is the same for all the formulas with a single row. () a. (p ∨ ¬p), (p → p), (p → (q → p)), ¬(p ∧ ¬p) b. -

Sets, Propositional Logic, Predicates, and Quantifiers

COMP 182 Algorithmic Thinking Sets, Propositional Logic, Luay Nakhleh Computer Science Predicates, and Quantifiers Rice University !1 Reading Material ❖ Chapter 1, Sections 1, 4, 5 ❖ Chapter 2, Sections 1, 2 !2 ❖ Mathematics is about statements that are either true or false. ❖ Such statements are called propositions. ❖ We use logic to describe them, and proof techniques to prove whether they are true or false. !3 Propositions ❖ 5>7 ❖ The square root of 2 is irrational. ❖ A graph is bipartite if and only if it doesn’t have a cycle of odd length. ❖ For n>1, the sum of the numbers 1,2,3,…,n is n2. !4 Propositions? ❖ E=mc2 ❖ The sun rises from the East every day. ❖ All species on Earth evolved from a common ancestor. ❖ God does not exist. ❖ Everyone eventually dies. !5 ❖ And some of you might already be wondering: “If I wanted to study mathematics, I would have majored in Math. I came here to study computer science.” !6 ❖ Computer Science is mathematics, but we almost exclusively focus on aspects of mathematics that relate to computation (that can be implemented in software and/or hardware). !7 ❖Logic is the language of computer science and, mathematics is the computer scientist’s most essential toolbox. !8 Examples of “CS-relevant” Math ❖ Algorithm A correctly solves problem P. ❖ Algorithm A has a worst-case running time of O(n3). ❖ Problem P has no solution. ❖ Using comparison between two elements as the basic operation, we cannot sort a list of n elements in less than O(n log n) time. ❖ Problem A is NP-Complete.