On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities †

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classifying Material Implications Over Minimal Logic

Classifying Material Implications over Minimal Logic Hannes Diener and Maarten McKubre-Jordens March 28, 2018 Abstract The so-called paradoxes of material implication have motivated the development of many non- classical logics over the years [2–5, 11]. In this note, we investigate some of these paradoxes and classify them, over minimal logic. We provide proofs of equivalence and semantic models separating the paradoxes where appropriate. A number of equivalent groups arise, all of which collapse with unrestricted use of double negation elimination. Interestingly, the principle ex falso quodlibet, and several weaker principles, turn out to be distinguishable, giving perhaps supporting motivation for adopting minimal logic as the ambient logic for reasoning in the possible presence of inconsistency. Keywords: reverse mathematics; minimal logic; ex falso quodlibet; implication; paraconsistent logic; Peirce’s principle. 1 Introduction The project of constructive reverse mathematics [6] has given rise to a wide literature where various the- orems of mathematics and principles of logic have been classified over intuitionistic logic. What is less well-known is that the subtle difference that arises when the principle of explosion, ex falso quodlibet, is dropped from intuitionistic logic (thus giving (Johansson’s) minimal logic) enables the distinction of many more principles. The focus of the present paper are a range of principles known collectively (but not exhaustively) as the paradoxes of material implication; paradoxes because they illustrate that the usual interpretation of formal statements of the form “. → . .” as informal statements of the form “if. then. ” produces counter-intuitive results. Some of these principles were hinted at in [9]. Here we present a carefully worked-out chart, classifying a number of such principles over minimal logic. -

Propositional Logic, Modal Logic, Propo- Sitional Dynamic Logic and first-Order Logic

A I L Madhavan Mukund Chennai Mathematical Institute E-mail: [email protected] Abstract ese are lecture notes for an introductory course on logic aimed at graduate students in Com- puter Science. e notes cover techniques and results from propositional logic, modal logic, propo- sitional dynamic logic and first-order logic. e notes are based on a course taught to first year PhD students at SPIC Mathematical Institute, Madras, during August–December, . Contents Propositional Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Axiomatisations . . Maximal Consistent Sets and Completeness . . Compactness and Strong Completeness . Modal Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Correspondence eory . . Axiomatising valid formulas . . Bisimulations and expressiveness . . Decidability: Filtrations and the finite model property . . Labelled transition systems and multi-modal logic . Dynamic Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Axiomatising valid formulas . First-Order Logic . Syntax . . Semantics . . Formalisations in first-order logic . . Satisfiability: Henkin’s reduction to propositional logic . . Compactness and the L¨owenheim-Skolem eorem . . A Complete Axiomatisation . . Variants of the L¨owenheim-Skolem eorem . . Elementary Classes . . Elementarily Equivalent Structures . . An Algebraic Characterisation of Elementary Equivalence . . Decidability . Propositional Logic . Syntax P = f g We begin with a countably infinite set of atomic propositions p0, p1,... and two logical con- nectives : (read as not) and _ (read as or). e set Φ of formulas of propositional logic is the smallest set satisfying the following conditions: • Every atomic proposition p is a member of Φ. • If α is a member of Φ, so is (:α). • If α and β are members of Φ, so is (α _ β). We shall normally omit parentheses unless we need to explicitly clarify the structure of a formula. -

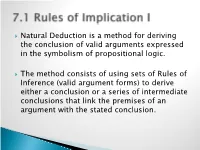

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

Propositional Logic - Basics

Outline Propositional Logic - Basics K. Subramani1 1Lane Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering West Virginia University 14 January and 16 January, 2013 Subramani Propositonal Logic Outline Outline 1 Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Subramani Propositonal Logic (i) The Law! (ii) Mathematics. (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. (Paradox). Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Motivation Why Logic? Subramani Propositonal Logic (ii) Mathematics. (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. (Paradox). Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Motivation Why Logic? (i) The Law! Subramani Propositonal Logic (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. (Paradox). Statements, Symbolic Representations and Semantics Boolean Connectives and Semantics Motivation Why Logic? (i) The Law! (ii) Mathematics. Subramani Propositonal Logic (iii) Computer Science. Definition Statement (or Atomic Proposition) - A sentence that is either true or false. Example (i) The board is black. (ii) Are you John? (iii) The moon is made of green cheese. (iv) This statement is false. -

Logic in Computer Science

P. Madhusudan Logic in Computer Science Rough course notes November 5, 2020 Draft. Copyright P. Madhusudan Contents 1 Logic over Structures: A Single Known Structure, Classes of Structures, and All Structures ................................... 1 1.1 Logic on a Fixed Known Structure . .1 1.2 Logic on a Fixed Class of Structures . .3 1.3 Logic on All Structures . .5 1.4 Logics over structures: Theories and Questions . .7 2 Propositional Logic ............................................. 11 2.1 Propositional Logic . 11 2.1.1 Syntax . 11 2.1.2 What does the above mean with ::=, etc? . 11 2.2 Some definitions and theorems . 14 2.3 Compactness Theorem . 15 2.4 Resolution . 18 3 Quantifier Elimination and Decidability .......................... 23 3.1 Quantifiier Elimination . 23 3.2 Dense Linear Orders without Endpoints . 24 3.3 Quantifier Elimination for rationals with addition: ¹Q, 0, 1, ¸, −, <, =º ......................................... 27 3.4 The Theory of Reals with Addition . 30 3.4.1 Aside: Axiomatizations . 30 3.4.2 Other theories that admit quantifier elimination . 31 4 Validity of FOL is undecidable and is r.e.-hard .................... 33 4.1 Validity of FOL is r.e.-hard . 34 4.2 Trakhtenbrot’s theorem: Validity of FOL over finite models is undecidable, and co-r.e. hard . 39 5 Quantifier-free theory of equality ................................ 43 5.1 Decidability using Bounded Models . 43 v vi Contents 5.2 An Algorithm for Conjunctive Formulas . 44 5.2.1 Computing ¹º ................................... 47 5.3 Axioms for The Theory of Equality . 49 6 Completeness Theorem: FO Validity is r.e. ........................ 53 6.1 Prenex Normal Form . -

Methods of Proof Direct Direct Contrapositive Contradiction Pc P→ C ¬ P ∨ C ¬ C → ¬ Pp ∧ ¬ C

Proof Methods Methods of proof Direct Direct Contrapositive Contradiction pc p→ c ¬ p ∨ c ¬ c → ¬ pp ∧ ¬ c TT T T T F Section 1.6 & 1.7 T F F F F T FT T T T F FF T T T F MSU/CSE 260 Fall 2009 1 MSU/CSE 260 Fall 2009 2 How are these questions related? Proof Methods h1 ∧ h2 ∧ … ∧ hn ⇒ c ? 1. Does p logically imply c ? Let p = h ∧ h ∧ … ∧ h . The following 2. Is the proposition (p → c) a tautology? 1 2 n propositions are equivalent: 3. Is the proposition (¬ p ∨ c) is a tautology? 1. p ⇒ c 4. Is the proposition (¬ c → ¬ p) is a tautology? 2. (p → c) is a tautology. Direct 5. Is the proposition (p ∧ ¬ c) is a contradiction? 3. (¬ p ∨ c) is a tautology. Direct 4. (¬ c → ¬ p)is a tautology. Contrapositive 5. (p ∧ ¬ c) is a contradiction. Contradiction MSU/CSE 260 Fall 2009 3 MSU/CSE 260 Fall 2009 4 © 2006 by A-H. Esfahanian. All Rights Reserved. 1- Formal Proofs Formal Proof A proof is equivalent to establishing a logical To prove: implication chain h1 ∧ h2 ∧ … ∧ hn ⇒ c p1 Premise p Tautology Given premises (hypotheses) h1 , h2 , … , hn and Produce a series of wffs, 2 conclusion c, to give a formal proof that the … . p1 , p2 , pn, c . p k, k’, Inf. Rule hypotheses imply the conclusion, entails such that each wff pr is: r . establishing one of the premises or . a tautology, or pn _____ h1 ∧ h2 ∧ … ∧ hn ⇒ c an axiom/law of the domain (e.g., 1+3=4 or x > x+1 ) ∴ c justified by definition, or logically equivalent to or implied by one or more propositions pk where 1 ≤ k < r. -

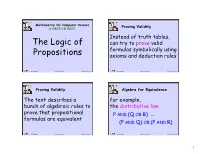

Propositional Logic (PDF)

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See Textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus P

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus Ponens. 6. Simplification. 7. X -- A very common student mistake; can't use Simplification unless the major con- nective of the premise is a conjunction. 8. Disjunctive Syllogism. 9. X -- Fallacy of Denying the Antecedent. 10. X 11. Constructive Dilemma. 12. See textbook. 13. Hypothetical Syllogism. 14. Hypothetical Syllogism. 15. Conjunction. 16. See textbook. 17. Addition. 18. Modus Ponens. 19. X -- Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent. 20. Disjunctive Syllogism. 21. X -- not HS, the (D v G) does not match (D v C). This is deliberate to make sure you don't just focus on generalities, and make sure the entire form fits. 22. Constructive Dilemma. 23. See textbook. 24. Simplification. 25. Modus Ponens. 26. Modus Tollens. 27. See textbook. 28. Disjunctive Syllogism. 29. Modus Ponens. 30. Disjunctive Syllogism. Step 2 Exercises #1 1 Z A 2. (Z v B) C / Z C 3. Z (1)Simp. 4. Z v B (3) Add. 5. C (2)(4)MP 6. Z C (3)(5) Conj. For line 4 it is easy to get locked into line 2 and strategy 1. But they do not work. #2 1. K (B v I) 2. K 3. ~B 4. I (~T N) 5. N T / ~N 6. B v I (1)(2) MP 7. I (6)(3) DS 8. ~T N (4)(7) MP 9. ~T (8) Simp. 10. ~N (5)(9) MT #3 See textbook. #4 1. H I 2. I J 3. -

CS245 Logic and Computation

CS245 Logic and Computation Alice Gao December 9, 2019 Contents 1 Propositional Logic 3 1.1 Translations .................................... 3 1.2 Structural Induction ............................... 8 1.2.1 A template for structural induction on well-formed propositional for- mulas ................................... 8 1.3 The Semantics of an Implication ........................ 12 1.4 Tautology, Contradiction, and Satisfiable but Not a Tautology ........ 13 1.5 Logical Equivalence ................................ 14 1.6 Analyzing Conditional Code ........................... 16 1.7 Circuit Design ................................... 17 1.8 Tautological Consequence ............................ 18 1.9 Formal Deduction ................................. 21 1.9.1 Rules of Formal Deduction ........................ 21 1.9.2 Format of a Formal Deduction Proof .................. 23 1.9.3 Strategies for writing a formal deduction proof ............ 23 1.9.4 And elimination and introduction .................... 25 1.9.5 Implication introduction and elimination ................ 26 1.9.6 Or introduction and elimination ..................... 28 1.9.7 Negation introduction and elimination ................. 30 1.9.8 Putting them together! .......................... 33 1.9.9 Putting them together: Additional exercises .............. 37 1.9.10 Other problems .............................. 38 1.10 Soundness and Completeness of Formal Deduction ............... 39 1.10.1 The soundness of inference rules ..................... 39 1.10.2 Soundness and Completeness -

Argument Forms and Fallacies

6.6 Common Argument Forms and Fallacies 1. Common Valid Argument Forms: In the previous section (6.4), we learned how to determine whether or not an argument is valid using truth tables. There are certain forms of valid and invalid argument that are extremely common. If we memorize some of these common argument forms, it will save us time because we will be able to immediately recognize whether or not certain arguments are valid or invalid without having to draw out a truth table. Let’s begin: 1. Disjunctive Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “The coin is either in my right hand or my left hand. It’s not in my right hand. So, it must be in my left hand.” Let “R”=”The coin is in my right hand” and let “L”=”The coin is in my left hand”. The argument in symbolic form is this: R ˅ L ~R __________________________________________________ L Any argument with the form just stated is valid. This form of argument is called a disjunctive syllogism. Basically, the argument gives you two options and says that, since one option is FALSE, the other option must be TRUE. 2. Pure Hypothetical Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “If you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll get a hole in one; and if you get a hole in one you’ll win the game. So, if you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll win the game.” Let “B”=”You hit the ball in on this turn”, “H”=”You get a hole in one”, and “W”=”you win the game”. -

Philosophy 109, Modern Logic Russell Marcus

Philosophy 240: Symbolic Logic Hamilton College Fall 2014 Russell Marcus Reference Sheeet for What Follows Names of Languages PL: Propositional Logic M: Monadic (First-Order) Predicate Logic F: Full (First-Order) Predicate Logic FF: Full (First-Order) Predicate Logic with functors S: Second-Order Predicate Logic Basic Truth Tables - á á @ â á w â á e â á / â 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 Rules of Inference Modus Ponens (MP) Conjunction (Conj) á e â á á / â â / á A â Modus Tollens (MT) Addition (Add) á e â á / á w â -â / -á Simplification (Simp) Disjunctive Syllogism (DS) á A â / á á w â -á / â Constructive Dilemma (CD) (á e â) Hypothetical Syllogism (HS) (ã e ä) á e â á w ã / â w ä â e ã / á e ã Philosophy 240: Symbolic Logic, Prof. Marcus; Reference Sheet for What Follows, page 2 Rules of Equivalence DeMorgan’s Laws (DM) Contraposition (Cont) -(á A â) W -á w -â á e â W -â e -á -(á w â) W -á A -â Material Implication (Impl) Association (Assoc) á e â W -á w â á w (â w ã) W (á w â) w ã á A (â A ã) W (á A â) A ã Material Equivalence (Equiv) á / â W (á e â) A (â e á) Distribution (Dist) á / â W (á A â) w (-á A -â) á A (â w ã) W (á A â) w (á A ã) á w (â A ã) W (á w â) A (á w ã) Exportation (Exp) á e (â e ã) W (á A â) e ã Commutativity (Com) á w â W â w á Tautology (Taut) á A â W â A á á W á A á á W á w á Double Negation (DN) á W --á Six Derived Rules for the Biconditional Rules of Inference Rules of Equivalence Biconditional Modus Ponens (BMP) Biconditional DeMorgan’s Law (BDM) á / â -(á / â) W -á / â á / â Biconditional Modus Tollens (BMT) Biconditional Commutativity (BCom) á / â á / â W â / á -á / -â Biconditional Hypothetical Syllogism (BHS) Biconditional Contraposition (BCont) á / â á / â W -á / -â â / ã / á / ã Philosophy 240: Symbolic Logic, Prof. -

The Development of Modus Ponens in Antiquity: from Aristotle to the 2Nd Century AD Author(S): Susanne Bobzien Source: Phronesis, Vol

The Development of Modus Ponens in Antiquity: From Aristotle to the 2nd Century AD Author(s): Susanne Bobzien Source: Phronesis, Vol. 47, No. 4 (2002), pp. 359-394 Published by: BRILL Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4182708 Accessed: 02/10/2009 22:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bap. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. BRILL is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Phronesis. http://www.jstor.org The Development of Modus Ponens in Antiquity:' From Aristotle to the 2nd Century AD SUSANNE BOBZIEN ABSTRACT 'Aristotelian logic', as it was taught from late antiquity until the 20th century, commonly included a short presentationof the argumentforms modus (ponendo) ponens, modus (tollendo) tollens, modus ponendo tollens, and modus tollendo ponens.