The Limits of the Global Village: Globalization, Nations and the State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interventionism in the Era of Globalization

Pratical theory 9 Stanisław Kowalczyk, Roman Sobiecki Interventionism in the era of globalization Interventionism is a system of influ- entities, weakening of their competitive- ence of a nation state or an integration ness, which consequently can translate group on the economy as a whole or on into deterioration of the macroeconomic separate sectors, whose role is to allevi- situation in the long run. A manifesta- ate contradictions between the micro- tion of unreliability of interventionism and macroeconomic objectives. can also be the temptation to overuse the tools of interventionism to achieve strictly The tools used for this purpose are of political, party or electoral goals. There- economic, legal and administrative na- fore, the trick is to find the right relations ture (Sobiecki, 2015). More specifically between interventionism and the market – economic and legal, as well as admin- activity. istrative and legal, and sometimes persua- The beginnings of interventionism sive. Thus, interventionism is not an oc- date back to ancient times, when Athens casional and accidental influence of a state was fully supplied with the goods of for- through its institutions, but an ordered eign origin, which was the reason for the system subordinated to the achievement collapse of the domestic production. This of specified objectives. situation forced the introduction of duties Interventionism is necessary to achieve on imported goods to protect its own pro- reasonableness on a macroeconomic scale duction. It can, therefore, be concluded and to alleviate contradictions with the that it was a little taste of interventionism, approach to the reasonableness from the so it is as old as the institution of the state. -

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: the Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: The Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises A report by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital With the support of: Ross Baird Lily Bowles Saurabh Lall The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and busi- ness support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs will create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits. Ultimately, we believe that SGBS can help lift countries out of poverty. ANDE is part of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization. For more information please visit www.aspeninstitute.org/ande. Village Capital Village Capital sources, trains, and invests in impactful seed-stage enter- prises worldwide. Inspired by the “village bank” model in microfinance, Village Capital programs leverage the power of peer support to provide opportunity to entrepreneurs that change the world. Our investment pro- cess democratizes entrepreneurship by putting funding decisions into the hands of entrepreneurs themselves. Since 2009, Village Capital has served over 300 ventures on five continents building disruptive innovations in agriculture, education, energy, environmental sustainability, financial services, and health. For more information, please visit www.vilcap.com. Report released June 2013 Cover photo by TechnoServe Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Background a. Incubators and Accelerators in Traditional Business Sectors b. Incubators and Accelerators in the Impact Investing Sector III. Data and Methodology IV. -

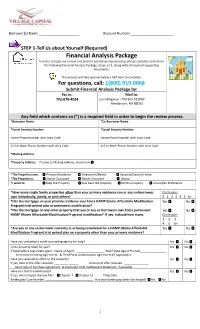

Financial Analysis Package in Order to Begin Our Review and Prevent Any Delays in Processing, Please Complete and Return

Borrower(s) Name Account Number STEP 1-Tell Us about Yourself (Required) Financial Analysis Package In order to begin our review and prevent any delays in processing, please complete and return the following Financial Analysis Package, Steps 1-11, along with all required supporting documents. This process will take approximately a half hour to complete. For questions, call: 1(800) 919-0068 Submit Financial Analysis Package by: Fax to: Mail to: 702-670-4024 Loss Mitigation – PO Box 531667 Henderson, NV 89053 Any field which contains an (*) is a required field in order to begin the review process. *Borrower Name *Co-Borrower Name *Social Security Number *Social Security Number Home Phone Number with Area Code Home Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code *Mailing Address *Property Address If same as Mailing Address, check here *The Property is my: Primary Residence Investment/Rental Seasonal/Second Home *The Property is: Owner Occupied Renter Occupied Vacant *I want to: Keep the Property Give back the property Sell the property Unsure/No Preference *How many single family properties other than your primary residence you or any co-borrowers Circle one: own individually, jointly, or with others? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6+ *Has the mortgage on your primary residence ever had a HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Yes No Program) trial period plan or permanent modification? *Has the mortgage on any other property that you or any co-borrowers own had a permanent Yes No HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Program) modification? If yes, indicate how many. -

Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa

sustainability Article Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa Jytte Agergaard * , Susanne Kirkegaard and Torben Birch-Thomsen Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 13, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (T.B.-T.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the next twenty years, urban populations in Africa are expected to double, while urban land cover could triple. An often-overlooked dimension of this urban transformation is the growth of small towns and medium-sized cities. In this paper, we explore the ways in which small towns are straddling rural and urban life, and consider how insights into this in-betweenness can contribute to our understanding of Africa’s urban transformation. In particular, we examine the ways in which urbanism is produced and expressed in places where urban living is emerging but the administrative label for such locations is still ‘village’. For this purpose, we draw on case-study material from two small towns in Tanzania, comprising both qualitative and quantitative data, including analyses of photographs and maps collected in 2010–2018. First, we explore the dwindling role of agriculture and the importance of farming, businesses and services for the diversification of livelihoods. However, income diversification varies substantially among population groups, depending on economic and migrant status, gender, and age. Second, we show the ways in which institutions, buildings, and transport infrastructure display the material dimensions of urbanism, and how urbanism is planned and aspired to. Third, we describe how well-established middle-aged households, independent women (some of whom are mothers), and young people, mostly living in single-person households, explain their visions and values of the ways in which urbanism is expressed in small towns. -

Mill's "Very Simple Principle": Liberty, Utilitarianism And

MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE": LIBERTY, UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM MICHAEL GRENFELL submitted for degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048607 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048607 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H^S £ S F 6SI6 ABSTRACT OF THESIS MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE'*: LIBERTY. UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM 1 The thesis aims to examine the political consequences of applying J.S. Mill's "very simple principle" of liberty in practice: whether the result would be free-market liberalism or socialism, and to what extent a society governed in accordance with the principle would be free. 2 Contrary to Mill's claims for the principle, it fails to provide a clear or coherent answer to this "practical question". This is largely because of three essential ambiguities in Mill's formulation of the principle, examined in turn in the three chapters of the thesis. 3 First, Mill is ambivalent about whether liberty is to be promoted for its intrinsic value, or because it is instrumental to the achievement of other objectives, principally the utilitarian objective of "general welfare". -

Village Officers Handbook

OHIO VILLAGE OFFICER’S HANDBOOK ____________________________________ March 2017 Dear Village Official: Public service is both an honor and challenge. In the current environment, service at the local level may be more challenging than ever before. This handbook is one small way my office seeks to assist you in meeting that challenge. To that end, this handbook is designed to be updated easily to ensure you have the latest information at your fingertips. Please feel free to forward questions, concerns or suggestions to my office so that the information we provide is accurate, timely and relevant. Of course, a manual of this nature is not to be confused with legal advice. Should you have concerns or questions of a legal nature, please consult your statutory legal counsel, the county prosecutor’s office or your private legal counsel, as appropriate. I understand the importance of local government and want to make sure we are serving you in ways that meet your needs and further our shared goals. If my office can be of further assistance, please let us know. I look forward to working with you as we face the unique challenges before us and deliver on our promises to the great citizens of Ohio. Thank you for your service. Sincerely, Dave Yost Auditor of State 88 East Broad Street, Fifth Floor, Columbus, Ohio 43215-3506 Phone: 614-466-4514 or 800-282-0370 Fax: 614-466-4490 www.ohioauditor.gov This page is intentionally left blank. Village Officer’s Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Home Rule I. Definition ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 II. -

The Need for State in the Economy- Epistemological Approach

Annals of the University of Petroşani, Economics, 10(3), 2010, 291-300 291 THE NEED FOR STATE IN THE ECONOMY- EPISTEMOLOGICAL APPROACH ANCA-ŞTEFANIA SAVA * ABSTRACT: The aim of this paper is to discuss the need for state in the economy, in an epistemological viewpoint. It presents in a critical manner the ideas on the state of the mercantilism and physiocracy representatives, of the classical and Keynesian economists and of the so-called current „the new liberal orthodoxy”. It is noticed that the need for a minimal state, as a condition of proper functioning of the society, has been justified even by those who have criticized it (classical liberals), being recognized that a society can not be conceived anarchic and utopian. If during ’29-’33s, the philosophy of laisser-faire was replaced by the Keynesian doctrine, and ’70s have placed the welfare state in a crisis of legitimacy, starting from 2008 we can talk of a resurgence of the Keynesian paradigm, according to which government intervention is seen as a way to stimulate the economic recovery. KEY WORDS: Welfare-state; the minimal state; Keynesianism; macroeconomic policy; School of economic thought; classicism; monetarism JEL CLASSIFICATION: I38, H10, E12, E61, B10, B12, B52, E61 1. THE NEED FOR STATE INTERVENTION IN THE ECONOMY FROM THE MERCANTILISTS AND PHYSIOCRATS’ PERSPECTIVE Mercantilists were the first which made reference to the role of the state in the economy, paving the way for the assertion of physiocracy and classical liberalism doctrine. This particular school of thought specific for the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries has dominated the economic life in the theoretical and practical matter, until the mid-XVIII century. -

Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: a Case Study of Guangzhou

sustainability Case Report Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: A Case Study of Guangzhou Fan Wu 1, Ling-Hin Li 2,* ID and Sue Yurim Han 2 1 Department of Construction Management, School of Civil Engineering and Transportation, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510630, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Real Estate and Construction, Faculty of Architecture, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-2859-2128 Received: 21 May 2018; Accepted: 19 June 2018; Published: 21 June 2018 Abstract: Rapid economic development in China has generated substantial demand for urban land for development, resulting in an unprecedented urbanization process. The expansion of urbanized cities has started to engulf rural areas, making the urban–rural boundary less and less conspicuous in China. Urban encroachment has led to a rapid shrinkage of the rural territory as the rural–urban migration has increased due to better job opportunities and living standards in the urban cities. Urban villages, governed by a rural property rights mechanism, have started to emerge sporadically within urbanised areas. Various approaches, such as state-led, developer-led, or collective-led approaches, to redevelop these urban villages have been adopted with varying degrees of success. This paper uses a case-study framework to analyse the state–market interplay in two very different urban village redevelopment cases in Guangzhou. By an in-depth comparative analysis of the two regeneration cases in Guangzhou, which started within close proximity in terms of geographical location and timing, we are able to shed light on how completely different outcomes may result from different forms of state–market interplay. -

The Shifting of Village Autonomy Concept in Indonesia

THE SHIFTING OF VILLAGE AUTONOMY CONCEPT IN INDONESIA Abstract This research tries to examine comprehensively about the different concepts about village autonomy in Law No. 5 of 1979 and Law No. 6 of 2014. The results supposed to be contributed as scientific journal and other scientific work, which is valuable for scientific improvement in provincial autonomy law. Itsurely could be used by the local governments in Indonesia and hopefully in Asia as a framework to construct a strategic procedure of the village development. This study uses the conceptual approach and analysis approach as methods. The conceptual approach directed to examine the first legal issue related to differ autonomy concept in Law No. 5 of 1979 and Law No. 6 of 2014 while the analytical approach is used for assessing the alignment of the concept of village autonomy in Law No. 6 of 2014 with a constitutional mandate. The results found, there is improvements in the draft of Law No. 6 Year 2014 by increasing the funding source for the village, and guarantee the right to determine her village. A village, in Law No. 6 Year 2014, is possible to switch into a custom village. Keywords: village, village governance, village autonomy I. Introduction Enactment of the Law No. 6 Year 2014, constantly ended the village government setting in Law No. 32 Year 2004,1and a sign of the village model setting within a different law. Such condition had ever occurred in the New Order era by the emerging of Law No. 5 Year 1979 on Village (“Village Law”). This concept of Village Government may cause a lot of problems such as weakening the capacity of the village administration, policy form and the village unique 2. -

New Labour, Globalization, and the Competition State" by Philip G

Centerfor European Studies Working Paper Series #70 New Labour, Globalization, and the Competition State" by Philip G. Cemy** Mark Evans" Department of Politics Department of Politics University of Leeds University of York Leeds LS2 9JT, UK York YOlO SDD, U.K Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] • Will also be published in Econonry andSocitD' - We would like to thank the Nuffield Foundation, the Center for European Studies, Harvard University,and the Max-Planck-Institut fur Gesellschaftsforshung, Cologne, for their support during the writing of this paper. Abstract The concept of the Competition State differs from the "Post-Fordist State" of Regulation Theory, which asserts that the contemporary restructuring of the state is aimed at maintaining its generic function of stabilizing the national polity and promoting the domestic economy in the public interest In contrast, the Competition State focuses on disempowering the state from within with regard to a range of key tasks, roles, and activities, in the face of processes of globalization . The state does not merely adapt to exogenous structural constraints; in addition, domestic political actors take a proactive and preemptive lead in this process through both policy entrepreneurship and the rearticulation of domestic political and social coalitions, on both right and left, as alternatives are incrementally eroded. State intervention itself is aimed at not only adjusting to but also sustaining, promoting, and expanding an open global economy in order to capture its perceived -

The Castle and the Village: the Many Faces of Limited Access

01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 3 1 The Castle and the Village: The Many Faces of Limited Access jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi Access Denied No author in world literature has done more to give shape to the nightmarish challenges posed to access by modern bureaucracies than Franz Kafka. In his novel The Castle, “K.,” a land surveyor, arrives in a village ruled by a castle on a hill (see Kafka 1998). He is under the impression that he is to report for duty to a castle authority. As a result of a bureaucratic mix-up in communications between the cas- tle officials and the villagers, K. is stuck in the village at the foot of the hill and fails to gain access to the authorities. The villagers, who hold the castle officials in high regard, elaborately justify the rules and procedures to K. The more K. learns about the castle, its officials, and the way they relate to the village and its inhabitants, the less he understands his own position. The Byzantine codes and formalities gov- erning the exchanges between castle and village seem to have only one purpose: to exclude K. from the castle. Not only is there no way for him to reach the castle, but there is also no way for him to leave the village. The villagers tolerate him, but his tireless struggle to clarify his place there only emphasizes his quasi-legal status. Given K.’s belief that he had been summoned for an assignment by the authorities, he remains convinced that he has not only a right but also a duty to go to the cas- tle! How can a bureaucracy operate in direct opposition to its own stated pur- poses? How can a rule-driven institution be so unaccountable? And how can the “obedient subordinates” in the village wield so much power to act in their own self- 3 01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 4 4 jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi interest? But because everyone seems to find the castle bureaucracy flawless, it is K. -

Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Stephen, Matthew D. Article — Accepted Manuscript (Postprint) Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance Global Governance Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Stephen, Matthew D. (2017) : Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance, Global Governance, ISSN 1942-6720, Brill Nijhoff, Leiden, Vol. 23, Iss. 3, pp. 483-502, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02303009 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215866 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu This article was published by Brill in Global Governance, Vol. 23 (2017), Iss. 3, pp. 483–502 (2017/08/19): https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02303009.