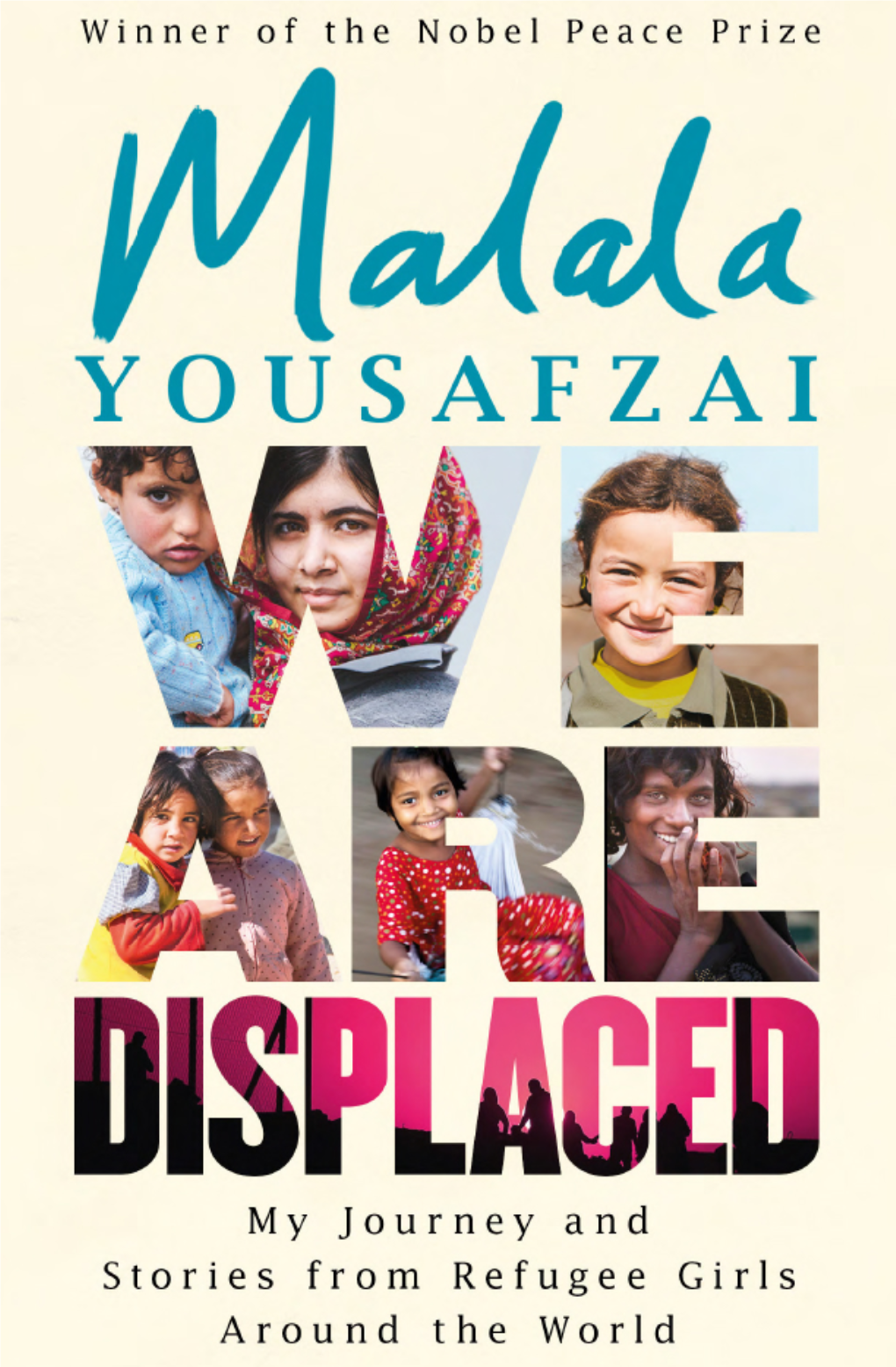

We Are Displaced V1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reading List for Refugee Week 2020

Living in Limbo: a reading list for Refugee Week 2020 Cover illustration: 'LandEscape' created by Jal Kong age 15 from South Sudan, currently living in Kakuma refugee camp. Contents Fiction for Younger Readers ...................................................................................................... 2 Fiction for Young Adults ............................................................................................................. 7 Adult Fiction ............................................................................................................................. 12 Non-Fiction ............................................................................................................................... 16 1 | P a g e Fiction for Younger Readers Nadine Dreams of Home by Bernard Ashley Age recommendation 7+ A touching yet serious story with an ultimately uplifting ending. Nadine doesn't like her new life. She doesn't speak the language, she can't understand what's going on, and more than anything, it's just not home. Especially since her father isn't here with them in the UK. But it just wasn't safe in Goma anymore, not with the uprising and the violence of the rebel soldiers. So, Nadine tries to find something in her new life that will remind her of the happy memories of Africa. Particularly suitable for struggling, reluctant and dyslexic readers aged 7+ Give Me Shelter edited by Tony Bradman Age recommendation 9+ The phrase 'asylum-seeker' is one we see in the media all the time. It stimulates fierce and controversial debate, in arguments about migration, race and religion. The movement of people from poor or struggling countries to those where there may be opportunities for a better life is a constant in human history, but it is something with particular relevance in our own time. This collection of short stories shows us people who have been forced to leave their homes or families to seek help and shelter elsewhere. -

Building Back Better – Gender

Building back better: Gender-responsive strategies to address the impact of COVID-19 on girls’ education According to UNESCO almost 1.8 billion students around the world have been affected by school closures as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Around 320 million of them are in India.1 New research suggests that increased rates of poverty, household responsibilities, child labour, teenage pregnancy may prevent as many as 20 million secondary school-aged girls around the world from ever returning to the classroom.2 RISKS TO GIRLS’ EDUCATION Just a few months of interruption in learning has a greater impact on girls than boys, and will disproportionately affect marginalised girls from scheduled castes and tribes, religious minorities or those from families who have lost their livelihoods during the pandemic in India: Government online learning Prior to the pandemic, girls were provisions are likely to deepen already twice as likely as boys education inequity, given that to have less than four years of under half of urban households education.3 and 14.9% of rural households 2X 4 have internet access. Prevailing norms mean that girls Media reporting suggests that are often the least likely members the economic impact of Covid-19 of the household to access the on families may increase the risk internet, and the unequal burden of early dropout from education, of domestic and care work that as girls become more vulnerable girls shoulder creates additional to child marriage, child labour, barriers to access distance trafficking, violence or sexual learning. abuse.5 The pressure on teachers may ultimately exacerbate India’s teacher shortage once the pandemic passes: • Teachers have not been trained to develop online learning alternatives, increasing stress and reducing the quality of distance learning provisions. -

Bell Ringers for the Week of October 28, 2019 UNIT 3: Cultural Patterns

Bell Ringers for the week of October 28, 2019 UNIT 3: Cultural Patterns and Processes (Halloween, GenDer, Toponymy) PrepareD by Ken Keller [email protected] *Students should always be prompted, probed, so to speak, to answer the WHY question when responding to geographic inquiry J Question #1: What criteria are useD to Determine the quality of life of women in a country? With those variables in minD, preDict the best anD worst places in the world for women to live. ID variables Elaboration of quality of life variables The Best and Worst places to be a woman, 2019@ https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2019/10/peril-progress-prosperity-womens-well-being- around-the-world-feature/ One geographic theme here is the battle between local/indigenous cultural traditions and modern/global cultural values. What role, if any, do global forces and interactions have on traditional societies with respect to women? From March 2018. Saudi women unveiled. How Saudi society has changed in relation to the life of women @ https://www.cbsnews.com/news/saudi-women-unveiled/ From June, 2018. Six things that Saudi women still can’t do @? http://www.theweek.co.uk/60339/things-women-cant-do-in-saudi-arabia Saudi Women unveiled. How life is changing for women in Saudi Arabia from 60 Minutes, 2018 @ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNFNxFlLzrc (7:41) The countries where Muslim women can’t wear veils (2017) @ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/life/burka-bans-the-countries-where-muslim-women-cant-wear- veils/ From May, 2015. Eight Things Women Are Banned From Wearing Around the World: http://www.theweek.co.uk/63244/seven-things-women-are-banned-from-wearing-around-the-world Different Hijab styles for Muslim women in different parts of the world: http://www.hijabiworld.com/different-hijab-styles-for-muslim-woman-around-the-world/ Ex. -

Malala Fund Calculated the Potential Impact of the Current School Closures on Girls’ Dropout Numbers in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries

Almost 90% of the world’s countries have shut their schools in efforts to slow the transmission of COVID-19.1 Alongside school closures, governments are also imposing social distancing measures and restricting the movement of people, goods and services, leading to stalled economies. While this disruption to education and the expected reduction in global growth have far-reaching effects for all, their impact will be particularly detrimental to the most disadvantaged students and their families, especially in poorer countries. The educational consequences of COVID-19 will last beyond the period of school closures, disproportionately affecting marginalised girls. This paper uses insights from previous health and financial shocks to understand how the current global pandemic could affect girls’ education outcomes for years to come. It details how governments and international institutions can mitigate the immediate and longer-term effects of the pandemic on the most marginalised girls. The paper considers the 2014- 15 Ebola epidemic and the 2008 global financial crisis, which both have some parallels to the impact of COVID-19. We find that marginalised girls are more at risk than boys of dropping out of school altogether following school closures and that women and girls are more vulnerable to the worst effects of the current pandemic. Drawing on data from the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone, we estimate that approximately 20 million more secondary school-aged girls could be out of school after the crisis has passed2, if dropouts increase by the same rate. Longer-term, poorer countries may struggle to provide sufficient financing for education, especially to support schools, teachers and students to fight reemergence of the virus and stay safe from indirect effects of further outbreaks. -

IRC Ambassador Book List

IRC Ambassador Book List Refugee by Alan Gratz Young Adult (8+) All three young people will go on harrowing journeys in search of refuge. All will face unimaginable dangers–from drownings to bombings to betrayals. But for each of them, there is always the hope of tomorrow. And although Josef, Isabel, and Mahmoud are separated by continents and decades, surprising connections will tie their stories together in the end. The Lightless Sky: A Twelve-Year-Old Refugee’s Harrowing Escape from Afghanistan and His Extraordinary Journey Across Half the World by Gulwali Passarlay Young Adult (8+) A gripping, inspiring, and eye-opening memoir of fortitude and survival—of a twelve-year-old boy’s traumatic flight from Afghanistan to the West—that puts a face to one of the most shocking and devastating humanitarian crises of our time. Escape From Aleppo by N.H Senzai Young Adult (8+) It is December 17, 2010: Nadia’s twelfth birthday and the beginning of the Arab Spring. Soon anti-government protests erupt across the Middle East and, one by one, countries are thrown into turmoil. As civil war flares in Syria and bombs fall across Nadia’s home city of Aleppo, her family decides to flee to safety. Inspired by current events, this novel sheds light on the complicated situation in Syria that has led to an international refugee crisis, and tells the story of one girl’s journey to safety I Lived on Butterfly Hill by Marjorie Agosín Young Adult (8+) Celeste Marconi is a dreamer. She lives peacefully among friends and neighbors and family in the idyllic town of Valparaiso, Chile, until the time comes when even Celeste, with her head in the clouds, can”t deny the political unrest that is sweeping through the country. -

519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190

GIRLS-2019/10/15 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION GIRLS’ EDUCATION RESEARCH AND POLICY SYMPOSIUM: LEARNING ACROSS A LIFETIME Washington, D.C. Tuesday, October 15, 2019 Opening Remarks and Panel: MODERATOR: CHRISTINA KWAUK Fellow, Center for Universal Education The Brookings Institution BHAGYASHRI DENGLE Regional Director, Asia Plan International HUGO GORST-WILLIAMS Team Leader, Girls’ Education UK DFID ROBERT JENKINS Chief, Education Associate Director, Programme Division, UNICEF LEANNA MARR Director, Office of Education USAID MARTHA MUHWEZI Executive Director, FAWE Africa Intervening Early: Bringing Gender Into Early Childhood Education: MODERATOR: DANA SCHMIDT Senior Program Officer Echidna Giving PRESENTER: SAMYUKTA SUBRAMANIAN 2019 Echidna Global Scholar The Brookings Institution VRINDA DATTA Director of the Centre for Early Childhood Education Development Ambedkar University, Delhi ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 GIRLS-2019/10/15 2 SUMAN SACHDEVA 2015 Echidna Global Scholar The Brookings Institution Empowerment at Adolescence: STEM Skills for Girls’ Leadership and Innovation: MODERATOR: SARAH GAMMAGE Director of Gender, Economic Empowerment, and Livelihoods ICRW NASRIN SIDDIQA 2019 Echidna Global Scholar The Brookings Institution MALIHA KHAN Chief Programs Officer Malala Fund MEIGHAN STONE Senior Fellow, Women and Foreign Policy Program Council on Foreign Relations Entering Adulthood: Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and Girls’ Transitions -

Asian American Pacific Islander Booklist

Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 5-2021 Asian American Pacific Islander Booklist Children's Book Committee. Bank Street College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Children's Book Committee. Bank Street College of Education (2021). Asian American Pacific Islander Booklist. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recently-Published Recommended Books by and/or about the AAPI Community Arranged by Age Published from 2015 to early 2021 May 2021 Background A month ago, we formed a subcommittee to produce a short list of recommended books, from our Best Books List archives, centered on AAPI characters, authors, and illustrators. This was in direct response to spikes in unprovoked anti-Asian violence in the past year. That process sparked many debates over which ones to include. After that experience, the subcommittee returned to our archives for a closer inspection. We wanted to create a larger resource for readers from infancy to age 18.We also wanted to be able to deliver it within a reasonable timeframe, so here is how we created the list you see below. Methodology 1. First, we combed our recent Best Books list (BBL) archives for books that we have recommended, from our most recently published list (2020) back to the 2016 edition (meaning, books published from 2015 to 2019). -

Refugee Children's and YA Literature

Kathy G. Short, 2021 Children’s & Adolescent Literature on Refugee Experiences Displacement Due to Violence and War Picturebooks Beckwith, Kathy (2005). Playing War. Illus. Lea Lyon. Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House. RF Friends like to play war on the playground until a refugee child tells of losing his family in a real war. Hinojosa, Victor. (2020). A Journey toward Hope. Illus. Susan Guevara. Six Foot Press. RF The paths of four unaccompanied children from Central America through Mexico toward the U.S., and their reasons for their perilous journeys. Kaadan, Nadine (2018). Tomorrow. London: Lantana. RF A young boy in Syria is forced to stay inside due to the war around him. Lord, Michelle (2008). A Song for Cambodia. Illus. Shino Arihara. New York: Lee & Low. Bio True story of a young boy and musician who survives the Khmer Rouge killing fields and work camp. Robinson, Anthony (2009). Hamzat's Journey: A Refugee Diary. Illus. June Allan. London: Frances Lincoln. NF True story of a boy who lost his leg in a land mine during the Russia/Chechyna war and became a refugee. Smith, Icy (2010). Half Spoon of Rice: A Survival Story of the Cambodian Genocide. Illus. Sopaul Nhem. Manhattan Beach, CA: East West HF A boy separated from his family by the Khmer Rouge tries to survive when forced to work in the fields. Vander Zee, Ruth (2008). Always with You. Illus. Ronald Himler. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. HF A girl is orphaned when her village in Vietnam is bombed, comforted by her mother’s final words. Chapter Books Anderson, Natalie (2019). -

A Discussion Guide for Faithful Americans on Immigration Policies and Practices Table of Contents

OFFERING REFUGE: A DISCUSSION GUIDE FOR FAITHFUL AMERICANS ON IMMIGRATION POLICIES AND PRACTICES TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE Welcome from the Executive Director of Religions for Peace USA.............................................1 Welcome from the Moderator of Religions for Peace USA.........................................................2 Introduction from the Editors of “Offering Refuge”......................................................................3 About Religions for Peace USA...................................................................................................5 A Joint Statement from U.S. Religious Leaders and Communities Regarding U.S. Immigration and Refugee Policies and Practices............................................................................................8 Member Religious Communities of Religions for Peace USA...................................................10 ORIENTATION Week 1 Background and Definitions of Immigration Terms....................................................................11 Key United States Agencies That Deal With Immigration..........................................................14 Creating Some Ground Rules for Respectful Dialogue..............................................................15 Discerning the Sources That We Use........................................................................................17 THE DISCUSSION GUIDE Week 2 | Introduction..................................................................................................................21 -

A Mid-March Haggadah

COLOMBIA SOLIDARITY SEDER HAGGADDAH Letter to those about to begin a Seder in Solidarity with Colombia. Dear Brothers and Sisters, For me it is an honor and a great pleasure for us to be strengthening ties of friendship, solidarity and social commitment to work together for the resistance and sovereignty of the people. Thank you so much for sharing with us this moment in which food converts into symbols, representing the process that we put forward to continue walking together. We will be holding a Seder April 7th from 4-7PM, and it’s good to know that on an international level we will be able to gather, unite, and strengthen each other spiritually. The Seder is a space to share the historic memory of one people with another, which is important in order to not forget what has happened. If one does not know of the past, how can one resolve the present or future? That’s what memory is for. And history is not something dead on the pages of a book, but rather something alive, something living within ourselves. And we must tell it, show it. Just like with art...if I know how to sing but don’t sing, how do I show who I am? Thus memory is something that preserves one’s identity, and also serves to feed movements of resistance. It gives us knowledge, and with that information we can deepen our studies, and begin to understand another reality—the reality that the people live, but which isn’t published— and with that we are able to build a resistance. -

Education, Whether at Home Or in the Classroom, Has the Power to Promote Acceptance of Others’ Views and to Challenge Biases and Bigotry

I AM MALALA: A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS For more information about the resource guide, visit malala.gwu.edu or www.malala.org. A PREFACE FROM MALALA’S FATHER It is the elder generation’s duty to teach children the universal human values of truth, fairness, justice and equality. For this purpose, we have two institutions: families and schools. Education, whether at home or in the classroom, has the power to promote acceptance of others’ views and to challenge biases and bigotry. In patriarchal societies, women are expected to be obedient. A good girl should be quiet, humble and submissive. She is told not to question her elders, even if she feels that they are wrong or unjust. As a father, I did not silence Malala’s voice. I encouraged her to ask questions and to demand answers. As a teacher, I also imparted these values to the students at my school. I taught my female students to unlearn the lesson of obedience. I taught the boys to unlearn the lesson of so-called pseudo-honor. It is similarly the obligation of schools and universities to instill the principles of love, respect, dignity and universal humanism in their students. Girls and boys alike must learn to think critically, to stand up for what they believe is right and build an effective and healthy society. And these lessons are taught at schools through curriculum. Curricula teach young people how to be confident individuals and responsible citizens. I Am Malala is a story about a young girl’s campaign for human rights, especially a woman’s right to education. -

Early Marriages Among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon - a Case Study from the Old City of Saida

Early Marriages Among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon - A Case Study from the Old City of Saida Bahar Mahzooni Table of Content Introduction 3 Method 4 Ethical challenges 6 The Syrian refugees in Lebanon 7 Refugee right in Lebanon 8 Saida and the political division in Lebanon 10 The war in Syria and its impact on gender roles 12 Early marriage and regional variations in Syria 13 Early marriage and the continuous cycle of poverty 14 Marriage as a survival strategy 15 Protection as an incentive for early marriage 16 Early marriage and conflict-affected families 17 Loss of education 18 Conclusion 20 Bibliography 22 2 Bahar Mahzooni Introduction Globally, 12 million girls get married before they reach the age of 18 every year.1 The practice of early marriage affects young girls in several ways, such as their physical and mental health, education, financial status and their vocational opportunities. Moreover, early marriage is more common in countries with high levels of poverty and conflict; “Child marriage and teen pregnancy appear to be particularly high in insecure environments. Nine of the top 10 countries with the highest rates of child marriage are considered fragile states,”2 according to Rima Mourtada et al. in their qualitative study about the incentives that motivate early marriage among Syrian refugee communities in Lebanon. A report by Save the Children from 2014 concludes that the practice of early marriage drives many girls into depression, particularly if they are separated from family and friends and end up living a life in isolation after the marriage. Domestic violence is also more likely to occur within early marriages.