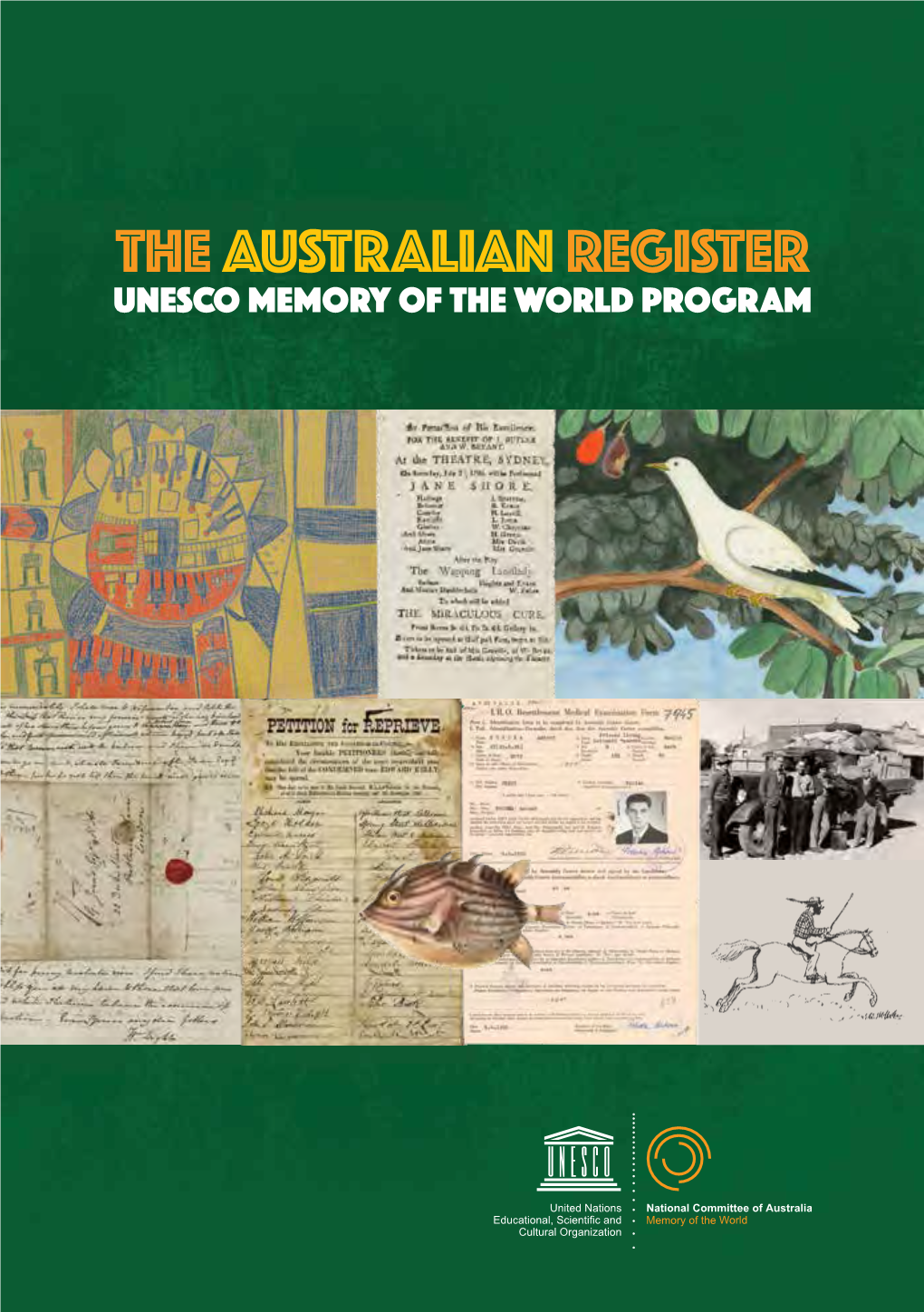

The Australian Register Unesco Memory of the World Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07 July 1980, No 3

AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER 1980/3 July 1980 •• • • • •• • •••: •.:• THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER ISSN 0156.8019 The Australiana Society P.O. Box A 378 Sydney South NSW 2000 1980/3, July 1980 SOCIETY INFORMATION p. k NOTES AND NEWS P-5 EXHIBITIONS P.7 ARTICLES - John Wade: James Cunningham, Sydney Woodcarver p.10 James Broadbent: The Mint and Hyde Park Barracks P.15 Kevin Fahy: Who was Australia's First Silversmith p.20 Ian Rumsey: A Guide to the Later Works of William Kerr and J. M. Wendt p.22 John Wade: Birds in a Basket p.24 NEW BOOKS P.25 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS p.14 OUR CONTRIBUTORS p.28 MEMBERSHIP FORM P.30 Registered for posting as a publication - category B Copyright C 1980 The Australiana Society. All material written or illustrative, credited to an author, is copyright. pfwdaction - aJLbmvt Kzmkaw (02) 816 U46 it Society information NEXT MEETING The next meeting of the Society will be at the Kirribilli Neighbourhood Centre, 16 Fitzroy Street, Kirribilli, at 7-30 pm on Thursday, 7th August, 1980. This will be the Annual General Meeting of the Society when all positions will be declared vacant and new office bearers elected. The positions are President, two Vice-Presidents, Secretary, Treasurer, Editor, and two Committee Members. Nominations will be accepted on the night. The Annual General Meeting will be followed by an AUCTION SALE. All vendors are asked to get there early to ensure that items can be catalogued and be available for inspection by all present. Refreshments will be available at a moderate cost. -

AUSTRALIA: COLONIAL LIFE and SETTLEMENT Parts 1 to 3

AUSTRALIA: COLONIAL LIFE AND SETTLEMENT Parts 1 to 3 AUSTRALIA: COLONIAL LIFE AND SETTLEMENT The Colonial Secretary's Papers, 1788-1825, from the State Records Authority of New South Wales Part 1: Letters sent, 1808-1825 Part 2: Special bundles (topic collections), proclamations, orders and related records, 1789-1825 Part 3: Letters received, 1788-1825 Contents listing PUBLISHER'S NOTE TECHNICAL NOTE CONTENTS OF REELS - PART 1 CONTENTS OF REELS - PART 2 CONTENTS OF REELS - PART 3 AUSTRALIA: COLONIAL LIFE AND SETTLEMENT Parts 1 to 3 AUSTRALIA: COLONIAL LIFE AND SETTLEMENT The Colonial Secretary's Papers, 1788-1825, from the State Records Authority of New South Wales Part 1: Letters sent, 1808-1825 Part 2: Special bundles (topic collections), proclamations, orders and related records, 1789-1825 Part 3: Letters received, 1788-1825 Publisher's Note "The Papers are the foremost collection of public records which relate to the early years of the first settlement and are an invaluable source of information on all aspects of its history." Peter Collins, former Minister for the Arts in New South Wales From the First Fleet in 1788 to the establishment of settlements across eastern Australia (New South Wales then encompassed Tasmania and Queensland as well), this project describes the transformation of Australia from a prison settlement to a new frontier which attracted farmers, businessmen and prospectors. The Colonial Secretary's Papers are a unique source for information on: Conditions on the prison hulks Starvation and disease in early Australia -

Emancipists and Escaped Convicts

Emancipists and escaped convicts Convicts who finished their sentence or were pardoned by the Governor were freed and given the same rights as free settlers. They were called emancipists. Other convicts tried to gain their freedom by escaping. Emancipists Although many emancipists became successful citizens, free settlers looked down on them because of their convict backgrounds. The emancipists believed they had the natural right to live in the colonies, because the colonies had been set up especially for them. Many emancipists owned large properties and made fortunes from the thriving wool industry. When she was 13 years old, Mary Reibey aussie fact stole a horse. As punishment, she was transported to Australia for seven years. Because there were very few Mary married a free settler and was women in the colonies, women “ emancipated. When her husband died, convicts were emancipated if “Mary took over his shipping business. they married free settlers. She had seven children to care for, but she ran the business successfully by herself. Over time, she made a fortune. 14 2SET_WAA_TXT_2pp.indd 14 5/12/08 1:43:44 PM A police magistrate could offer a ticket of leave to convicts who worked hard and behaved themselves. Convicts with tickets of leave Some convicts who behaved well qualified for a ‘ticket of leave’ or ‘certificate of freedom’. They became emancipists and could earn their own living. They were watched, however, for the rest of their sentence. If they misbehaved, their ticket could be cancelled. Escaped convicts Convict William Buckley escaped in 1803. In the penal colonies, convicts were not kept behind bars. -

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

William Buelow Gould--Convict Artist in Van Diemen's Land

PAP~:<:Rs AND PRoCE::8DJNGS OF THE ROYAL Sf.tf"IETY oF TASMANIA, VoLUME 9:3 WILLIAM BUELOW GOULD--CONVICT ARTIST IN VAN DIEMEN'S LAND By !SABELLA MEAD* (With 1 Plate) When I came first to the Launceston Museum I brought William Buelow Gould to Van Diemen's found very many paintings by a convict named Land. He writes of him:- Gould. Very soon visitors were asking me questions about him and I proceeded to read what had been " This poor wretch is another example of the written. It seemed very little. In fact, it amounted baneful effects produced by gambling. He to the notes that had been put together by Mr. has been a pupil of Mulreadys-his true name Henry Allport for an exhibition of Tasmanian art is Holland-his friends residing in Stafford are held in Hobart in 1931. These notes were published chinaware manufacturers. in the " Mercury " newspaper and then put together He got into a gambling set in Liverpool, lost in pamphlet form. Every subsequent writer on his money and to redeem it and being fond Gould has used them. of play he got initiated and became a regular When people said, however," vVhen was he born? member of the set of sharpers. When did he die? Was he marri.ed? Did he leave In the course of his practices he came to any family? Did he paint only in oil?", I had to London and was at one time intimate with reply, "I do not know." I am still not certain when the notorious Thurthill, the murderer, and he was born, but I know when he died. -

Susan Courtney – Middlesex

Bond of Friendship Susan Courtney – Middlesex Susan Courtney Date of Trial: 16 April 1817 Where Tried: Middlesex Gaol Delivery Crime: Having forged bank notes Sentence: 14 years Est YOB: 1793 Stated Age on Arrival: 25 Native Place: London Occupation: Servant Alias/AKA: Susannah Courtney, Susan Peck (m) Marital Status (UK): Children on Board: Surgeon’s Remarks: A common prostitute, insolent and mutinous Assigned NSW or VDL VDL On 8 April 1817 Susan (alternatively Susannah) Courtney was remanded in custody on two charges which were heard at the Old Bailey on 16 April 1817. Susan Courtney, 24, from New Prison, committed by R. Baker, Esq. charged on oath, with feloniously disposing of and putting away to John Austen the younger, a false, forged and counterfeited Bank note, purporting to be a note of the Governor and Company of the Bank of England, for payment of five pounds, knowing the same to be forged, with intent to defraud the said Governor and Company. Detained charged on oath, for putting away to John Austen, a counterfeit Bank-note, for Two pounds, knowing the same to be counterfeited, with intent to defraud the said Governor and Company.1 For the charge of feloniously and knowingly having a forged Bank of England note in her custody and possession, she pleaded guilty and was sentenced to transportation for fourteen years. No evidence was presented for the second charge and she was therefore found not guilty of this offence.2 Following the trial she was taken to Newgate Prison to await embarkation on the convict vessel which would transport her to the other side of the world. -

Tasmanian Creativity and Innovation Tasmanian Historical Studies. Volume 8. No 2 (2003): 28-39

Tasmanian Creativity and Innovation Tasmanian Historical Studies. Volume 8. No 2 (2003): 28-39. Rambling in Overdrive: Travelling Through Tasmanian Literature CA Cranston Two years ago I published an anthology of original and published writings about Tasmania titled Along these lines: From Trowenna to Tasmania1 — a mistake it turns out (as far as the title goes) as readers generally assume that Trowenna is some other place, rather than some other time. The idea was to situate various texts about Tasmania into context, so that when traveling the arterial highways of the heart- shaped island one was presented with stories and histories (time) that live on the sides of the road (place). This paper will address the theme of the conference (‘Originally Tasmanian. Creativity and Innovation in the Island State’) with a methodology similar to that ‘driving’ the anthology. It will examine the relationship between context (the origin) and text (the representation), and by implication, the relationship between natural and symbolic worlds. The ramble, which textually refers to the discursive — ideas, like automobiles, that ‘run about’ — will be accommodated, and as such will occasionally disrupt normal expectations of chronology, the historian’s purview. The motivation for the anthology came out of a need to experience at first hand niggling doubts about the textual construction of the island. I was a migrant so (in terms of the conference theme) I’m not ‘Originally Tasmanian’. I was living in a biotic community I knew nothing about and for which I had no language. I was presented with a textual culture I knew little about, and I was hungry for island stories. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Time Booksellers September 2020 Latestacquisitions

Time Booksellers September 2020 Latest Acquisitions Uploaded on our website on September 1st some 467 titles. To view a Larger image click on the actual image then the back arrow. To order a book, click on 'Click here to ORDER' and then the ORDER button. If you wish to continue viewing books, click the back arrow. You will return to the list of books you were viewing. To continue adding books to your order simply repeat on the next book you want. When you have finished viewing or searching click on 'View shopping cart'. Your list of books will be shown. To remove any unwanted books from the shopping cart simply click 'Remove the item'. When satisfied with your order click "Proceed with order" follow the prompts, this takes you to the Books and Collectibles secure ordering page. To search our entire database of books (over 30000 titles), go to our website. www.timebookseller.com.au 111933 A'BECKETT, GILBERT ABBOTT; CRUIKSHANK, GEORGE. The Comic Blackstone. Part II.- of Real Property. Post 12mo; pp. xiv, 92 - 252; engraved title page, text illustrated with one other engraving, bound in contemporary half leather with marbled boards, good copy.London; Published at The Punch Office, 92 Fleet Street; 1856. Click here to Order $50 98279 ADAMS, JOHN D. The Victorian Historical Journal. Index to Volumes. 51 to 60. Issues Nos. 199 to 233 1980 - 1989. Firs Edition; Demy 8vo; pp. xi, 203; original stiff wrapper, minor browning to edges of wrapper, volume numbers written in ink on spine, otherwise a very good copy. -

Genealogical Society of Tasmania Inc

GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF TASMANIA INC. Volume 18 Number 1—June 1997 GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF TASMANIA INC. PO Box 60 Prospect Tasmania 7250 Patron: Emeritus Professor Michael Roe Executive: President Mr David Harris (03) 6424 5328 Vice President Mrs Anne Bartlett (03) 6344 5258 Vice President Mr Rex Collins (03) 6431 1113 Executive Secretary Mrs Dawn Collins (03) 6431 1113 Executive Treasurer Ms Sharalyn Walters (03) 6452 2845 Committee: Mrs Betty Calverley Miss Betty Fletcher Mr Doug Forrest Mrs Isobel Harris Mrs Pat Harris Mr Ray Hyland Mrs Denise McNeice Mrs Christine Morris Mrs Colleen Read Mrs Rosalie Riley Exchange Journal Coordinator Mrs Thelma McKay (03) 6229 3149 Journal Editor Mrs Rosemary Davidson (03) 6278 2464 Journal Coordinator Mr David Hodgson (03) 6229 7185 Library Coordinator Huon Branch (03) 6264 1335 Members’ Interests and AGCI Mr Allen Wilson (03) 6244 1837 Membership Secretary Ms Vee Maddock (03) 6243 9592 Publications Coordinator Mrs Anne Bartlett (03) 6344 5258 Public Officer Mr Jim Wall (03) 6248 1773 Research Coordinator Mr John Dare (03) 6424 7889 Sales Coordinator Mrs Pat Harris (03) 6344 3951 TAMIOT Coordinator Mrs Betty Calverley (03) 6344 5608 VDL Heritage Index Mr Neil Chick (03) 6228 2083 Branches of the Society Burnie: PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 Devonport: PO Box 587 Devonport Tasmania 7310 Hobart: GPO Box 640 Hobart Tasmania 7001 Huon: PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 Launceston: PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 Volume 18 Number 1 June 1997 ISSN 0159 0677 Journal Committee Rosemary Davidson, Cynthia O’Neill, Maurice Appleyard, Jeannine Connors, David Freestun, David Hodgson, Charles Hunt, Lucy Knott, Vee Maddock, Denise McNeice and Kate Ramsay. -

Science Do Australian and New Zealand Newspapers Publish?

Australian Journalism Review 25 (1) July 2003: 129-143 How much ‘real’ science do Australian and New Zealand newspapers publish? By Steve McIlwaine ABSTRACT Ten metropolitan or national newspapers – nine Australian and one New Zealand – were analysed over either seven or six years for their content of science stories according to strict criteria aimed at filtering out “non-core” science, such as computer technology, as well as what was considered non-science and pseudo- science. The study sought to establish the proportions of “real” science to total editorial content in these newspapers. Results were compared with similar content in US, UK, European and South-East Asian dailies. Introduction Although quite rigorous surveys by science-based organisations in Britain, the United States and Australia (Saulwick poll 1989, AGB McNair poll 1997) have shown uniformly that news consumers want to see or hear much more about science in news media, significantly above their appetite for sport and politics, news media appear not to have responded. Despite a substantial increase from a very low base in what is described as science news in the past 30 years (Arkin 1990, DITAC 1991, p.35-43, Harris, 1993, McCleneghan, 1994) and especially in the 1990s (Metcalfe and Gascoigne 1995), the increase seems not to have kept pace with apparent demand. The “blame” for such responses – or non-responses – to audience data have been studied previously (Riffe and Belbase 1983, Culbertson and Stempel 1984, Thurlow and Milo 1993, Beam 1995) in relation to such areas as overseas and medical news and appear to indicate in part an inertia, conservatism or hostility among senior news executives. -

THOTKG Production Notes Final REVISED FINAL

SCREEN AUSTRALIA, LA CINEFACTURE and FILM4 Present In association with FILM VICTORIA ASIA FILM INVESTMENT GROUP and MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL A PORCHLIGHT FILMS and DAYBREAK PICTURES production true history of the Kelly Gang. GEORGE MACKAY ESSIE DAVIS NICHOLAS HOULT ORLANDO SCHWERDT THOMASIN MCKENZIE SEAN KEENAN EARL CAVE MARLON WILLIAMS LOUIS HEWISON with CHARLIE HUNNAM and RUSSELL CROWE Directed by JUSTIN KURZEL Produced by HAL VOGEL, LIZ WATTS JUSTN KURZEL, PAUL RANFORD Screenplay by SHAUN GRANT Based on the Novel by PETER CAREY Executive Producers DAVID AUKIN, VINCENT SHEEHAN, PETER CAREY, DANIEL BATTSEK, SUE BRUCE-SMITH, SAMLAVENDER, EMILIE GEORGES, NAIMA ABED, RAPHAËL PERCHET, BRAD FEINSTEIN, DAVID GROSS, SHAUN GRANT Director of Photography ARI WEGNER ACS Editor NICK FENTON Production Designer KAREN MURPHY Composer JED KURZEL Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Sound Designer FRANK LIPSON M.P.S.E. Hair and Make-up Designer KIRSTEN VEYSEY Casting Director NIKKI BARRETT CSA, CGA SHORT SYNOPSIS Inspired by Peter Carey’s Man Booker prize winning novel, Justin Kurzel’s TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG shatters the mythology of the notorious icon to reveal the essence behind the Life of Ned KeLLy and force a country to stare back into the ashes of its brutal past. Spanning the younger years of Ned’s Life to the time Leading up to his death, the fiLm expLores the bLurred boundaries between what is bad and what is good, and the motivations for the demise of its hero. Youth and tragedy colLide in the KeLLy Gang, and at the beating heart of this tale is the fractured and powerful Love story between a mother and a son.