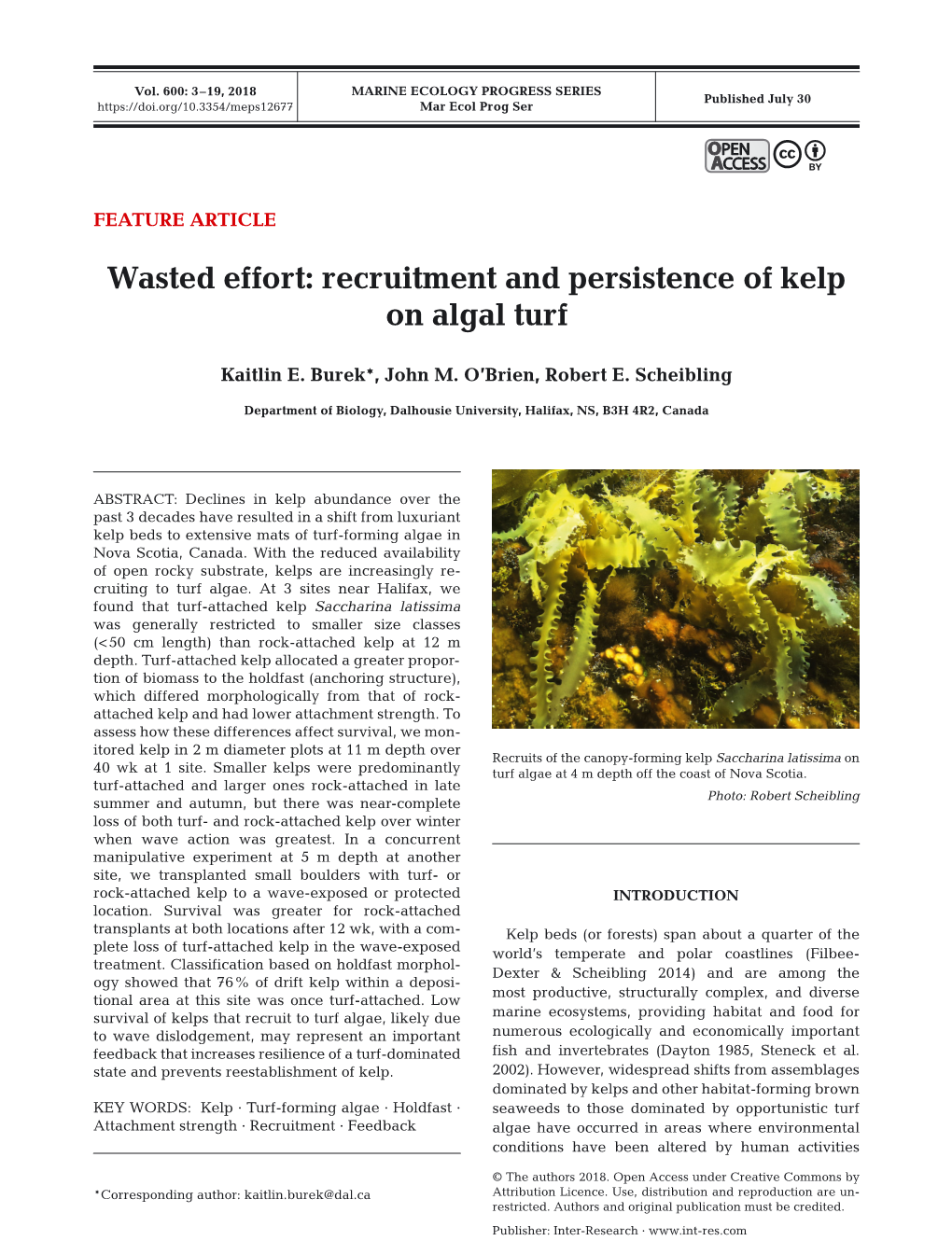

Wasted Effort: Recruitment and Persistence of Kelp on Algal Turf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

Fucus Vesiculosus Populations?

l MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 133: 191-201.1996 Published March 28 1 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Are neighbours harmful or helpful in Fucus vesiculosus populations? Joel C. Creed*,T. A. Norton, Joanna M. Kain (Jones) Port Erin Marine Laboratory, Port Erin. Isle of Man IM9 6JA, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: In order to investigate the effect of density on Fucus vesjculosus L. at all stages of its development, 2 experiments were carried out. A culture study in the laboratory found that increased density resulted in depressed growth and a negatively skewed population structure during the first month in the lives of freshly settled germlings. Intraspecific competition acts even at this early stage, and the limiting factor was probably nutrients. 'Two-sided' ('resource depletion') competition and an early scramble phase of growth may explain negative skewness in plant sizes. On the shore experi- mental thinning by reduction of the canopy resulted in increased macrorecruitment (apparent density) from a bank of microscopic plants which must have been present for some time. With increased thinning more macrorecruits loined the remaining plants, making population size structures highly posit~velyskewed. Thinning had no effect on reproduction In terms of the portion of biomass as repro- ductive tissue. Manipulative weedlng allows an assessment of the potent~alspore bank in seasonally reproductive seaweeds and revealed that there are always replacement plants in reserve to compen- sate for canopy losses. In E vesiculosus the performance of individuals early on is crucial to their sub- sequent survival to reproductive stage, as neighbours are generally competitively harmful. However, a failure to 'win' early on may not necessarily result in the ending of a small plant's life - the 'seed' bank still offers the individual a slim chance of survival and protects the population from harmful stochastic events KEY WORDS: Culture . -

Processing of Allochthonous Macrophyte Subsidies by Sandy Beach Consumers: Estimates of Feeding Rates and Impacts on Food Resources

Mar Biol DOI 10.1007/s00227-008-0913-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Processing of allochthonous macrophyte subsidies by sandy beach consumers: estimates of feeding rates and impacts on food resources Mariano Lastra · Henry M. Page · Jenifer E. Dugan · David M. Hubbard · Ivan F. Rodil Received: 29 January 2007 / Accepted: 8 January 2008 © Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract Allochthonous subsidies of organic material impact on drift macrophyte processing and fate and that the can profoundly inXuence population and community struc- quantity and composition of drift macrophytes could, in ture; however, the role of consumers in the processing of turn, limit populations of beach consumers. these inputs is less understood but may be closely linked to community and ecosystem function. Inputs of drift macro- phytes subsidize sandy beach communities and food webs Introduction in many regions. We estimated feeding rates of dominant sandy beach consumers, the talitrid amphipods (Megalor- Allochthonous inputs of organic matter can strongly inXu- chestia corniculata, in southern California, USA, and Tali- ence population and community structure in many eco- trus saltator, in southern Galicia, Spain), and their impacts systems (e.g., Polis and Hurd 1996; Cross et al. 2006). on drift macrophyte subsidies in Weld and laboratory exper- Such eVects are expected to be greatest where a highly iments. Feeding rate varied with macrophyte type and, for productive system interfaces with and exports materials to T. saltator, air temperature. Size-speciWc feeding rates of a relatively less productive system (Barrett et al. 2005). talitrid amphipods were greatest on brown macroalgae Ecosystems that are subsidized by allochthonous inputs (Macrocystis, Egregia, Saccorhiza and Fucus). -

Getative Tissues; the GDBH Predicts Metabolic Costs Associated with Them

J. Phycol. 35, 483±492 (1999) PHLOROTANNIN ALLOCATION AMONG TISSUES OF NORTHEASTERN PACIFIC KELPS AND ROCKWEEDS1 Kathryn L. Van Alstyne2 Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 James J. McCarthy III, Cynthia L. Hustead, and Laura J. Kearns Department of Biology, Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio 43022 Optimal defense theory (ODT) predicts antiher- Abbreviations: DM, dry mass; GDBH, growth±dif- bivore defensive compounds will be allocated so ferentiation balance hypothesis; ODT, optimal de- that the most valuable or most susceptible tissues fense theory will be best defended. The growth±differentiation balance hypothesis (GDBH) predicts that defense al- location will be a result of trade-offs between growth Plants allocate materials and energy among criti- and defense. Thus, these two theories predict op- cal functions such as maintenance, growth, repro- posite allocation patterns with respect to ``valuable,'' duction, and defense (Bazazz and Grace 1997 and actively growing meristematic and reproductive tis- citations therein). It is widely assumed the total sues. ODT predicts that meristems and reproductive amount of resources available for these functions is tissues should have higher defense levels than non- limited and all of these functions have signi®cant meristematic vegetative tissues; the GDBH predicts metabolic costs associated with them. Consequently, the defense levels of meristems and reproductive over evolutionary time there should be selection for tissues will be lower than vegetative tissues. We ex- individuals to distribute resources among functions amined allocation patterns of phlorotannins in 21 in ways that maximize overall ®tness, assuming that species of kelps (Order Laminariales) and rock- allocation strategies are not limited by physiological weeds (Order Fucales) from nine sites on the west or other constraints. -

Some Considerations for Analyzing Biodiversity Using Integrative

Some considerations for analyzing biodiversity using integrative metagenomics and gene networks Lucie Bittner, Sébastien Halary, Claude Payri, Corinne Cruaud, Bruno de Reviers, Philippe Lopez, Eric Bapteste To cite this version: Lucie Bittner, Sébastien Halary, Claude Payri, Corinne Cruaud, Bruno de Reviers, et al.. Some considerations for analyzing biodiversity using integrative metagenomics and gene networks. Biology Direct, BioMed Central, 2010, 5 (5), pp.47. 10.1186/1745-6150-5-47. hal-02922363 HAL Id: hal-02922363 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02922363 Submitted on 26 Aug 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Bittner et al. Biology Direct 2010, 5:47 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/5/1/47 HYPOTHESIS Open Access Some considerations for analyzing biodiversity using integrative metagenomics and gene networks Lucie Bittner1†, Sébastien Halary2†, Claude Payri3, Corinne Cruaud4, Bruno de Reviers1, Philippe Lopez2, Eric Bapteste2* Abstract Background: Improving knowledge of biodiversity will benefit conservation biology, enhance bioremediation studies, and could lead to new medical treatments. However there is no standard approach to estimate and to compare the diversity of different environments, or to study its past, and possibly, future evolution. -

Snps Reveal Geographical Population Structure of Corallina Officinalis (Corallinaceae, Rhodophyta)

SNPs reveal geographical population structure of Corallina officinalis (Corallinaceae, Rhodophyta) Chris Yesson1, Amy Jackson2, Steve Russell2, Christopher J. Williamson2,3 and Juliet Brodie2 1 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, UK 2 Natural History Museum, Department of Life Sciences, London, UK 3 Schools of Biological and Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK CONTACT: Chris Yesson. Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract We present the first population genetics study of the calcifying coralline alga and ecosystem engineer Corallina officinalis. Eleven novel SNP markers were developed and tested using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) genotyping to assess the population structure based on five sites around the NE Atlantic (Iceland, three UK sites and Spain), spanning a wide latitudinal range of the species’ distribution. We examined population genetic patterns over the region using discriminate analysis of principal components (DAPC). All populations showed significant genetic differentiation, with a marginally insignificant pattern of isolation by distance (IBD) identified. The Icelandic population was most isolated, but still had genotypes in common with the population in Spain. The SNP markers presented here provide useful tools to assess the population connectivity of C. officinalis. This study is amongst the first to use SNPs on macroalgae and represents a significant step towards understanding the population structure of a widespread, habitat forming coralline alga in the NE Atlantic. KEYWORDS Marine red alga; Population genetics; Calcifying macroalga; Corallinales; SNPs; Corallina 2 Introduction Corallina officinalis is a calcified geniculate (i.e. articulated) coralline alga that is wide- spread on rocky shores in the North Atlantic (Guiry & Guiry, 2017; Brodie et al., 2013; Williamson et al., 2016). -

ORGANIC CONSTITUENTS of PACIFIC COAST KELPS the Giant

ORGANIC CONSTITUENTS OF PACIFIC COAST KELPS By D. R. HOAGLAND, Assistant Chemist, Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California INTRODUCTION AND PLAN OF WORK The giant kelps of the Pacific coast have been regarded during recent years as commercially profitable sources of potash and iodin. The high content of these constituents in the kelp was first given prominence by Balch (i),1 and later the Bureau of Soils of the United States Depart- ment of Agriculture (4) made further studies and mapped out many of the beds. These investigations were followed by a widespread interest in kelps and it was the prevailing idea that these plants would furnish the raw material for industries of considerable magnitude. It seemed, however, that such predictions required further verification through more extended chemical studies than were available, since in many directions exact in- formation was entirely lacking. Accordingly the Chemical Laboratory of the California Experiment Station during the past year has carried on a general investigation of the subject the principal results of which are discussed in publications of this Station by Burd (3) and Stewart (32). While the potash and iodin values have, as a matter of course, received first attention in all discussions of a kelp industry, it has been apparent that any commercially valuable by-products of an organic nature would greatly enhance the possibilities of utilizing kelp with a margin of profit. Practically no studies of the organic constituents of the California kelps have been made prior to the writer's, and it is with this aspect of the investigations that the present paper deals.2 It is not the intention to regard the experiments herein described as forming in any sense a com- plete and final study of the numerous questions involved. -

BROWN ALGAE · HETEROKONTOPHYTA (PART II) Notebook Requirements (12 Drawings) 1

BROWN ALGAE · HETEROKONTOPHYTA (PART II) Notebook Requirements (12 drawings) 1. Macrocystis pyrifera – 4 drawings (thallus, scimitar blade (apical end), cross section of sporophyll, and sporophyll blade) 2. Nereocystis leutkeana –2 drawings (thallus and lateral section) 3. Laminaria setchellii – 1 drawings (thallus) 4. Alaria marginata – 1 drawing (thallus and cross section of sporophyll) 5. Egregia menziesii – 1 drawing (at least 2 different blade types and/or terminal blade) 6. Lessoniopsis littoralis – 1 drawing (thallus) 7. Unknowns – 2 Thallus drawings and steps in key C. Order Laminariales Family Laminariaceae Species: Macrocystis pyrifera • Examine and sketch the thallus of M. pyrifera. Label stipe, blades, sporophylls, holdfast, pneumatocysts and location of intercalary meristem • Examine and sketch the apical end of M. pyrifera noting the scimitar blade. • Draw a sporophyll blade and a vegetative blade. Q: Where is each type of blade located on the thallus? How can you visually tell them apart from each other? Species: Nereocystis leutkeana To transport sugars throughout the plant body of this large kelp, Nereocystis (and M. pyrifera) has sieve tubes in the outer medulla. • Draw the thallus of N. leutkeana, label stipe, pneuomatocyst, holdfast sporophylls, and sori (if present). • Prepare and draw a lateral section of the stipe. Identify and label mucilage ducts (if visible - in cortex), sieve plates (in medulla)/sieve elements (trumpet hyphae), cortex and medulla. Work on this together to get a good cross section. Q: What is the purpose of sieve plates? Q: Compare and contrast Macrocystis and Nereocystis: What morphological differences are there? Which species is annual? Which is perennial? What environment are each species found? (hint, check MAC) Q: What is the life history of Laminariales? Q: For algae in Laminariales – Is the macro-thallus (the algae we have in the water table) 1N or 2N? Understand the lifecycle of this order. -

Ochrophyta Part II Notebook Requirements (14 Drawings) 1

Ochrophyta Part II Notebook Requirements (14 drawings) 1. Desmarestia sp.- 2 drawings (thallus from press and trichothallic growth) 2. Laminaria setchelli- 3 drawings (thallus and sorus cross section) 3. Macrocystis pyrifera – 4drawings (entire thallus, apical end, transverse cross section, longitudinal section) 4. Nereocystis leutkeana – 1 drawings (entire thallus) 5. Pterygophora californica – 1 drawing (entire thallus) 6. Alaria marginata – 1 drawing (entire thallus from press) 7. Egregia menziesii – 2 drawing (entire thallus of adult plant, one brach of a young plant) 8. Unknown(s) - steps to key D. Order Desmarestiales Species: Desmarestia spp. • Draw the entire thallus of Desmarestia. (Use the herbarium pressing) • Look at a prepared slide and draw what you see. Q: What kind of growth does Desmarestia exhibit? E. Order Laminariales Family Laminariaceae Species: Laminaria setchellii The holdfast of this species is composed of stiff, branched haptera. Each holdfast produces a single, long stipe. Sori appear as irregular darkened patches on the blades, but not all blades have sori. 1. Prepare and draw a cross section of the sorus. Look for and label sporangia, cortex and medulla. 2. Examine and draw the overall thallus. Label holdfast, stipe, blade, sori and the location of the meristem. 3. Look at the prepared slide, draw and label what you see. Species: Macrocystis pyrifera To transport sugars throughout the plant body of this large kelp, M. pyrifera has sieve elements in the medulla. • Examine and sketch the thallus of M. pyrifera. Label stipe, blades, sporophylls, holdfast, pneumatocysts and location of intercalary meristem. • Examine and sketch the apical end of M. pyrifera noting the scimitar blade. -

Molecular Investigation Reveals Epi/Endophytic Extrageneric Kelp (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) Gametophytes Colonizing Lessoniopsis Littoralis Thalli

Botanica Marina 48 (2005): 426–436 ᮊ 2005 by Walter de Gruyter • Berlin • New York. DOI 10.1515/BOT.2005.056 Molecular investigation reveals epi/endophytic extrageneric kelp (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) gametophytes colonizing Lessoniopsis littoralis thalli Christopher E. Lanea,* and Gary W. Saunders tidal zones along the western Vancouver Island coast. Members of the Laminariales make up the majority of the Centre for Environmental and Molecular Algal Research, seaweed biomass in the intertidal zone of this region and University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New their size and distinctive morphology have made them an Brunswick, E3B 6E1, Canada, e-mail: [email protected] extensively studied order of brown algae (Lane et al. in *Corresponding author press). Members of the Laminariales exhibit an alternation of heteromorphic generations of different ploidy levels. The Abstract macroscopic sporophytes are well characterized and the morphological classification within the Laminariales is A recent molecular investigation of kelp systematics based on features of this diploid generation (Setchell and revealed mitochondrial sequences that gave phylogenies Gardner 1925). Kelp gametophytes are haploid, dioe- inconsistent with those based on nuclear and chloroplast cious and sexually dimorphic; male filaments are typically sequences for the species Lessoniopsis littoralis. smaller in diameter and more branched than their female Sequence from the mitochondrial nad6 region placed L. counterparts (McKay 1933, Hollenberg 1939). Our under- littoralis in the middle of a clade of Alaria species in our standing of the microscopic, filamentous, gametophytes trees, whereas Rubisco and nuclear ribosomal DNA is poor compared with that of the sporophytes, and a sequences resolved L. littoralis within the Alariaceae, but comprehensive morphological survey of kelp gameto- distinct from Alaria. -

Southern California Tidepool Organisms

Southern California Tidepool Organisms Bryozoans – colonial moss animals Cnidarians – stinging invertebrates Derby Hat Bryozoan Red Bryozoan Aggregating Anemone Giant Green Anemone Sunburst Anemone Eurystomella spp. Watersipora spp. Anthopleura elegantissima Anthopleura xanthogrammica Anthopleura sola closed closed closed open 2 in (5 cm) open 6.7 in (17 cm) open 6.5 in (12cm) Echinoderms – spiny-skinned invertebrates Sea Stars note signs of wasting Bat Star Brittle Star Ochre Star Giant Pink Sea Star Six Armed Sea Star Sunflower Star Patiria miniata (various genuses) Pisaster ochraceus Pisaster brevispinus Leptasterias spp. Pycnopodia helianthoides Purple or Red webbed arms 10 in 11 in 31.5 in Various sizes 4.7 in (12 cm) Long, thin arms (25 cm) (28 cm) 6 arms, 2.4 in(6 cm) (80 cm) Sand Dollar Sea Cucumbers Urchins note signs of balding Eccentric Sand Dollar California Sea Cucumber Warty Sea Cucumber Purple Urchins Red Urchins Dendraster excentricus Parastichopus californicus Parastichopus parvimensis Strongylocentrotus Strongylocentrotus purpuratus franciscanus has small 4 in 7in black tipped warts (10 cm) (17 cm) 4 in (10 cm) 16 in (40 cm) 10 in (25 cm) long (projections) Mollusks – soft invertebrates with a shell or remnant shell Snails (single, spiraled shelled invertebrate) Turban Snail Periwinkle Snail Kellet’s Whelk Snail Dog Whelk Snail Unicorn Whelk Snail Scaly Tube Snail Tegula spp. Littorina spp. Kelletia kelletii (Dogwinkles) Acanthinucella spp. Serpulorbis squamigerus Nucella spp. Top view 6 ½ in 2 in 1.6 in (16.5 cm) (5 cm) 1 in (2.5 cm) ½ in (1.5 cm) (4cm) 5 in (13 cm) Bi-Valves (2 shelled invertebrates) Abalone California Mussel Blue Mussel Olympia Oyster Pacific Oyster Rock Scallop Haliotis spp. -

Landmarks in Pacific North America Marine Phycology

Landmarks in Pacific North America Marine Phycology GEORGE F. PAPENFUSS Labore arlo de Flcolo fa o partamento de 8iolog(8 Facultad de Cfenclas UN M KNOWLEDGE of the marine algae of the Pacific coast of orth America hegins with the 1791-95 expedition of Captain George Vancouver. (See Anderson, 1960, for an excellent account of this expedition. ) On the rec ommendation of the botanist Sir Joseph Banks (who as a young man had been a member of the scientific staff on Cook's first voyage, 1768--71), Archibald Menzies, a surgeon, was appointed botanist of the Vancouver expedition. Menzies had earlier served on a fur-trading vessel plying the northeastem Pacific and had collected plants from the Bering Strait to Nootka Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, in the years 1787 and 1788 (Jepson, 1929b; Scagel, 1957, p. 4), but I hav e come across no records of algae collected by him at that time. As a young midshipman Vancouver had been to the northeastern Pacific with Cook's third voyage in 1778. Now, in 1791, his expedition consisted of two ships, the sloop Discovery and the armed tender Chatham. The ships cam e to the north Pacific by way of the Cape of Good Hope, Australia, New Zealand, Tahiti, and the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii). They sailed from Hawaii on March 16, 1792, sighted the Mendocino coast of Califomia ( or Nova Albion [New Britain], the name given to northem California and Oregon by Drake and the name by which thi s region was still known among English navigators in Vancouver's time) on April 18, and proceeded north to explore the coast.