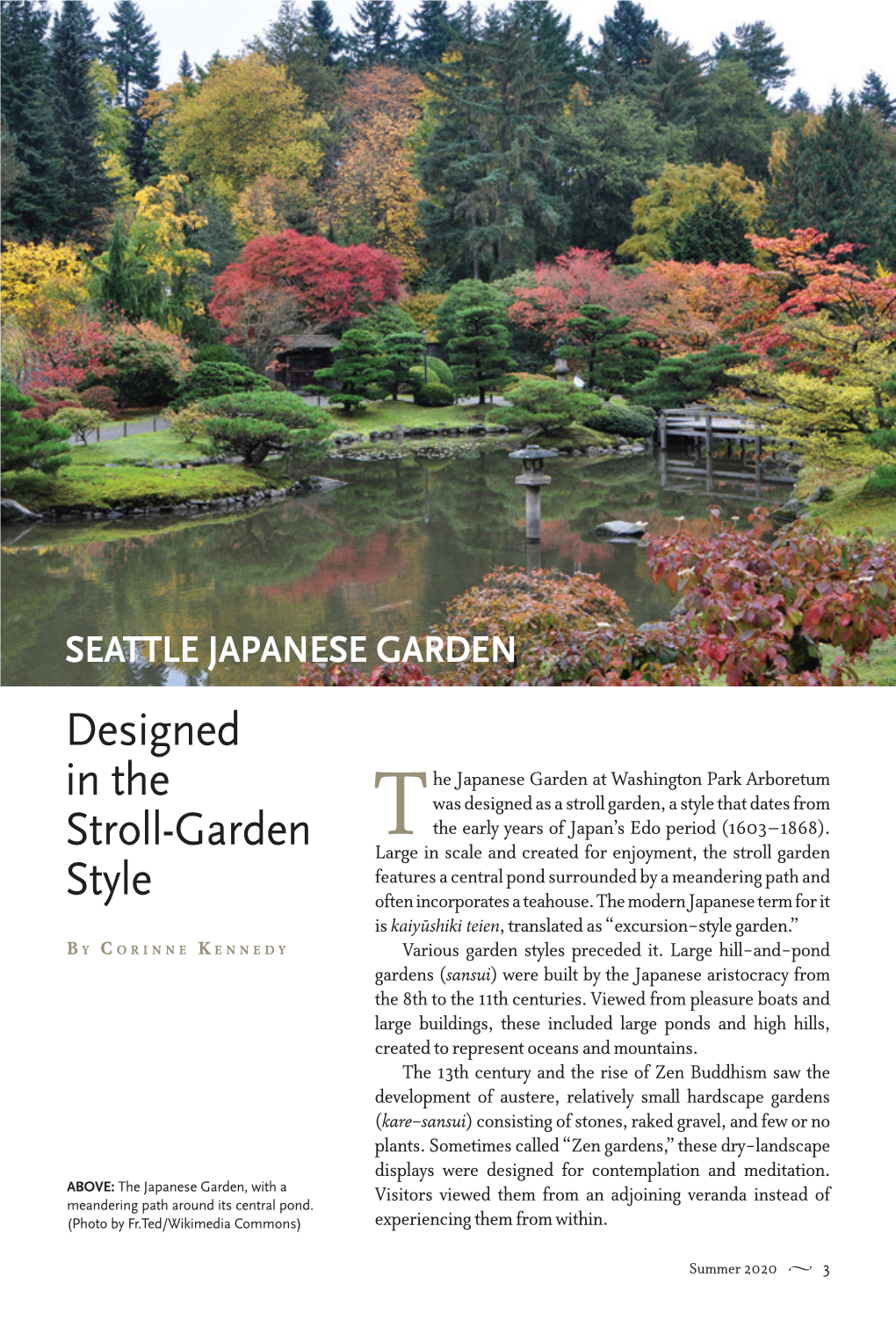

Seattle Japanese Garden: Designed in the Stroll-Garden Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Look Through the Heart Teahouse”

ShinKanAn Teahouse – The “Look Through the Heart Teahouse” 1. Introduction: History and Name • Our Teahouse in unique on the Central Coast. It is a traditional structure, using mostly Japanese joinery instead of nails, traditional tatami mats and hand-made paper sliding doors. Additionally, it is perhaps the only traditional Japanese Teahouse between the Greater Los Angeles area and the San Francisco peninsula, and the only one in California using California natives in an intentional Japanese style. • It was originally built in Kyoto during the postwar period: a wooden plaque on the wall near the entry doors commemorates the architect and the date: 1949. The Teahouse was a gift from the President of the Nippon Oil Company to a local resident, Mr. H. Royce Greatwood, as an expression of appreciation for his assistance after the war. It was shipped in wooden boxes, each piece numbered, and reassembled in Mr. Greatwood’s Hope Ranch lemon orchard in the early 1950’s. This teahouse is evidence of the tremendous efforts that were made to renew the ties of friendship between former wartime adversaries. • The rich cultural tradition of Cha-do, The Way of Tea, graces this teahouse. In 2000, it was given the name ShinKanAn , meaning “Look Through the Heart” by the 15th Grandmaster of the Urasenke Tea school, an unusual event. • The name was generously given in honor of Heartie Anne Look, a teacher of flower arrangement and Japanese culture for many years in the Santa Barbara community. This teahouse is being used and maintained in a manner authentic to the tradition of Cha-do. -

Based on the Most Classic Cocktails, but with an Asian Twist, These Cocktails Have Been Created by Roji for Anyone Who Follows the Path of Roji

Based on the most classic cocktails, but with an Asian twist, these cocktails have been created by Roji for anyone who follows the path of Roji. Please feel free to order your favorite classic cocktail even if it is not mentioned on this menu. The Nomu 13 Ketel One Vodka, Cointreau, Yuzu, Litchi, Bitters, Egg White Sweet with a Japanese twist Walking To Paradise 14 Johnnie Walker Black Label, Raspberry Liqueur, Lime, Butterscotch, Egg white Keep Walking... Budo 13 Hendrick’s Gin, Cointreau,Grapes, Cucumber, Elderfower, Lime Perfect Start Of Your Wonderful Evening Rojitini 14 Mount Gay Eclipse Rum, Elderfower, Lime Sweet & Classy Mao 15 Mount Gay Eclipse Rum, Zacapa 23 Rum, Lime, Liquor 43, Almond Syrup, Bitters Tiki Style Man with the Red Face 14 Strawberry and basil infused Don Julio Bianco, dry vermouth, lime Spicy challenge My Medicine Penicillin 16 Monkey Shoulder Whiskey, Laphroaig 10, Ginger syrup, Honey syrup, lime Smokey, Spicy A Bitter Berry 14 Tanqueray N°Ten, Campari, Homemade Strawberry Shiso shrub Twist on a Negroni After Dinner Cocktails Smokey ‘Cohiba’ Crusta 15 Zacapa 23, Maraschino liquor, Cherry Brandy, Lime, Smoke It’s Allowed To Smoke Inside... Gentlemen’s Agreement Club 29 Johnnie Walker Blue Label, Px Sherry, Poire Williams Eau de Vie, Bitters The Perfect After Dinner at The Fire Place Lost in Translation 14 Bulleit Rye Whiskey, Fernet Branca, Sugar, Bitters Champagne Cocktails Bellefeur Champagne 14 Roji Champagne, Elderfower ‘Belfeur’ The New Bellini Champagne Russian S. Punch 15 Belvedere Vodka, Raspberry Liqueur, Crème de Cassis Topped With Our Own Roji Champagne... Roji’s Mocktails Bangkok Non-Stop 7 Blue Eyes Tea, Litchi Syrup, Ginger Syrup, Yuzu Juice and Coke. -

Fact Sheet a Look Inside the Portland Japanese Garden

Fact Sheet A look inside the Portland Japanese Garden Address: Hours: Key Personnel: 611 SW Kingston Ave Summer Public Hours (March 13 - Sept. 30): Stephen Bloom, Chief Executive Officer Portland, Oregon 97208 ● Monday: Noon - 7 p.m. Sadafumi Uchiyama, Garden Curator ● Tuesday - Sunday: 10 a.m. - 7 p.m. Diane Durston, Arlene Schnitzer Curator of Culture, Art & Education Website: japanesegarden.org Cynthia Johnson Haruyama, Deputy Director Phone: 503.223.1321 Winter Public Hours (Oct. 1 - March 12) Cathy Rudd, Board of Trustees President Email: [email protected] ● Monday: Noon - 4 p.m. Dorie Vollum, Board of Trustees President-Elect and Cultural ● Tuesday - Sunday: 10 a.m. - 4 p.m. Crossing Campaign Co-Chair Quick Facts: Pricing: ● Year Established: 1963 Adults: $14.95 ● Total Annual Attendance: 356,000 in 2016 (up 20% from 2015) Seniors (65+): $12.95 ● Total Acreage: 8 public gardens spread over 12 acres College Students (with ID): $11.95 ● Total Volunteer Hours: 7,226 in 2016 Youth (6 - 17): $10.45 ● Total Members: 11,000 Children 5 and under: free ● Total Staff: 83 regular employees, including eight full-time gardeners ● Total Operating Budget: $9.5 million Photos, Videos & Logos: ● Click here for Photos of the Garden in every season ● Click here for Photos of Cultural Programming & Art Exhibitions ● Click here for Videos & B-roll ● Click here for Logos Media Inquiries: Erica Heartquist | [email protected] | 503.542.9339 Page 1 of 3 About the Portland Japanese Garden For more than 50 years, the Portland Japanese Garden has been a haven of serenity and tranquility, nestled in the scenic West Hills of Portland, OR. -

“The China of Santa Cruz”: the Culture of Tea in Maria Graham's

“The China of Santa Cruz”: The Culture of Tea in Maria Graham’s Journal of a Voyage to Brazil (Article) NICOLLE JORDAN University of Southern Mississippi he notion of Brazilian tea may sound like something of an anomaly—or impossibility—given the predominance of Brazilian coffee in our cultural T imagination. We may be surprised, then, to learn that King João VI of Portugal and Brazil (1767–1826) pursued a project for the importation, acclimatization, and planting of tea from China in his royal botanic garden in Rio de Janeiro. A curious episode in the annals of colonial botany, the cultivation of a tea plantation in Rio has a short but significant history, especially when read through the lens of Maria Graham’s Journal of a Voyage to Brazil (1824). Graham’s descriptions of the tea garden in this text are brief, but they amplify her thorough-going enthusiasm for the biodiversity and botanical innovation she encountered— and contributed to—in South America. Such enthusiasm for the imperial tea garden echoes Graham’s support for Brazilian independence, and indeed, bolsters it. In 1821 Graham came to Brazil aboard HMS Doris, captained by her husband Thomas, who was charged with protecting Britain’s considerable mercantile interests in the region. As a British naval captain’s wife, she was obliged to uphold Britain’s official policy of strict neutrality. Despite these circumstances, her Journal conveys a pro-independence stance that is legible in her frequent rhapsodies over Brazil’s stunning flora and fauna. By situating Rio’s tea plantation within the global context of imperial botany, we may appreciate Graham’s testimony to a practice of transnational plant exchange that effectively makes her an agent of empire even in a locale where Britain had no territorial aspirations. -

Growing an Herbal Tea Garden

Growing an Herbal Tea Garden By Lynn Heagney March 1, 2019 Teas if you please Growing an herbal tea garden is fun and rewarding. It involves selecting the site for your garden, deciding which herbs you’d like to grow, choosing a design, then planting, harvesting, and using the herbs you’ve grown in delicious teas. When you’re finished, not only will you have a wonderful source for all of your favorite teas, but you’ll also have a place that attracts butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds. Your first major decision is deciding where you’d like to locate your garden. Be sure to pick a site that has lots of sun, at least 4-6 hours per day because most herbs like sunny locations. Also, pick an area that drains well. Only mint likes “wet feet;” the rest prefer drier areas. If your only option is a damp area, you might consider planting your herbs in a raised bed, or in containers. It’s also nice if you can find a site that’s relatively close to your house so you can have fast and easy access to fresh herbs. Now you’re ready to choose which herbs you’d like to include in your garden. You can decide to establish a site exclusively for herbs used only in teas, or you can combine those with culinary herbs. You can also mix both types of herbs with a variety of flowers. If you’d like see how these combinations might work, plan a visit to the Discovery Gardens in Mount Vernon, where the Herb Garden and Cottage Garden provide inspiring examples of these strategies. -

Mizumoto Japanese Stroll Garden October, Open Daily 10 A.M.- 6 P.M

Hours Welcome to the April-September, open daily 10 a.m.- 7 p.m. IZUMOTO Mizumoto Japanese Stroll Garden October, open daily 10 a.m.- 6 p.m. M AN Admission Fees JAP ESE Adults: $3 Free admission, with member ID, ROLL GARDEN Children under 12: Free to members of Friends of the ST Garden or American Horticultural eene/Close Nathanael Gr Memorial Pa Koi fish food available: $1 Society reciprocal gardens. in ic Ave., Springfi eld, Miss rk 2400 S. Scen ouri 65807 Rentals & Tours The Mizumoto Japanese Stroll Garden and the * Stepping stones make it essential to look down and see adjacent Japanese Garden Pavilion are available for The Zig-Zag Bridge slows you down to where you are placing your feet. This act of slowing down rentals and weddings. Call 417-891-1515 or visit help create a meditative state. allows for a greater opportunity for contemplation. ParkBoard.org/Botanical/Rentals. Guided group tours and field trips may be scheduled through the Botanical Center or call 417-891-1515. Park Rules • Pets are permitted on a leash. • No swimming, wading, boating or fishing. • No harvesting of flowers, fruit, or plants. The Moon Bridge is curved to reflect the roundness of • No hammocks or attaching anything to trees. the rising moon. Japan is known as the Land of the Rising The Gazebo’s open-air design makes it • Weddings, special events and any activity including Sun. The moon is an important part of Japanese culture, ideal for meditation, tea ceremonies or 30 or more people requires a rental. -

Japanese Gardens at American World’S Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıv | Number ı | Fall 2008 Essays: The Long Life of the Japanese Garden 2 Paula Deitz: Plum Blossoms: The Third Friend of Winter Natsumi Nonaka: The Japanese Garden: The Art of Setting Stones Marc Peter Keane: Listening to Stones Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Tea and Sympathy: A Zen Approach to Landscape Gardening Kendall H. Brown: Fair Japan: Japanese Gardens at American World’s Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan Book Reviews 18 Joseph Disponzio: The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Garden of Versailles By Ian Thompson Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition By Robert Pogue Harrison Calendar 22 Tour 23 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor times. Still observed is a Marc Peter Keane explains Japanese garden also became of interior and exterior. The deep-seated cultural tradi- how the Sakuteiki’s prescrip- an instrument of propagan- preeminent Wright scholar tion of plum-blossom view- tions regarding the setting of da in the hands of the coun- Anthony Alofsin maintains ing, which takes place at stones, together with the try’s imperial rulers at a in his essay that Wright was his issue of During the Heian period winter’s end. Paula Deitz Zen approach to garden succession of nineteenth- inspired as much by gardens Site/Lines focuses (794–1185), still inspired by writes about this third friend design absorbed during his and twentieth-century as by architecture during his on the aesthetics Chinese models, gardens of winter in her narrative of long residency in Japan, world’s fairs. -

Teahouse N I T O

n i northwest:scale 1/8" t o b teahouse ea.r.thomson 2002 southeast:scale 1/8" N The Japanese Teahouse : Ritual and Form Buddhism had branched after about 600bc, into several distinct teachings. Of these, A Paper for M.Cohen’s Seminar on Architectural Proportion Mahayana (meaning 'big raft') Buddhism worked its way to Tibet, Mongolia, China, Korea May 2002, UBC | SoA and Japan. Of these five regional variations is the 'intuitive' school of Mayahana - or Zen. Submitted by a.r.thomson Zen (strictly literally!) means, 'meditation that leads to insight'. In order to make some sense of the Teahouse design, and more specifically its mode of Mahakasyapa, apparently, was the only acolyte present at The Flower Sermon, who proportioning, scale and materiality, it is necessary to understand something of the context understood. The Flower Sermon, it is said, was one where, "Standing on a mountain with his out of which the ‘Culture of Tea’, aka. ’Teaism’ first developed. This paper will attempt to disciples around him, Buddha did not on this occasion resort to words. He simply held aloft distill some sense of this ambient culture, and then relate the aesthetic of Zen, to the a golden lotus." (H.Smith, pg 134) components of the Teahouse proper, and finally, conclude with an examination of the proportions used in the Teahouse design. UBC’s Nitobe Teahouse was the primary resource Mahakasyapa was declared the Buddha's successor. 28 patriarchs later, in 520ad, studied, which is unique in that it is a ‘traditional’ structure on foreign soil, and thus Bodhidharma introduced the teaching of Zen to Japan. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people. -

San Francisco Japanese Tea Garden by Mary Yee

RAP GARDENSC IN FOCUS Explore Sites That Participate in the AHS Reciprocal Admissions Program San Francisco Japanese Tea Garden by Mary Yee ESTLED IN Golden Gate Park, the San Francisco Jap- Nanese Tea Garden is a little world unto its own, although it’s hardly a secret. One of the country’s oldest pub- lic Japanese gardens, it’s been around for over 125 years and is a popular des- tination for locals and tourists. Stone lanterns, pagodas, cherry trees, bonsai and much more are packed into about 5 acres of undulating terrain. A waterfall tumbles down a rocky hillside to a large pond filled with colorful koi. In the dry garden, or karasansui, raked gravel serves as a metaphor for water. Madison Sink, communications as- sociate for the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department, which oversees the garden, explains a proper Japanese “tea garden is a small, intimate space attached to a tea house where tea ceremonies are hosted.” She says, “Our garden is a stroll Above: This collection of dwarf shrubs on a garden designed for walking through that hillside adjacent to the Temple Gate once often includes hills and ponds. We were belonged to the Hagiwara family. Left: The named in the late 1800s, when ‘Japanese highly-arched drum bridge is a visitor favorite. Tea Garden’ was a ubiquitous term used for all Japanese-style gardens.” According to head gardener Steven Pit- senbarger, the collection includes Hinoki FROM FAIR ATTRACTION TO GARDEN cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa), Japanese The garden originated as an exhibit built black pine (Pinus thunbergii), and blue by George Turner Marsh to represent a Atlas cedar (Cedrus atlantica ‘Glauca’). -

Unfolding Place-Making Strategies for Attracting Tourists Among Tea Service Retailers in Istanbul, Turkey

Unfolding Place-making Strategies for Attracting Tourists among Tea Service Retailers in Istanbul, Turkey Figure 1: Turkish Tea (Zuniga, 2014) Saranyu Laemlak MSc Tourism, Society and Environment Wageningen University 2019 I A master’s thesis ‘Unfolding Place-making Strategies for Attracting Tourists among Tea Service Retailers in Istanbul, Turkey’ Saranyu Laemlak 921119495010 Submission date: March 13th, 2020 Thesis code: GEO-80436 Supervisor: dr. Ana Aceska & dr.ir. Joost Jongerden Examiner: prof. dr. Edward Huijbens Wageningen University and Research Department of Environmental Sciences Cultural Geography Chair Group MSc Tourism, Society and Environment II Disclaimer: This thesis is a student report produced as part of the Master Program Leisure, Tourism and Environment of Wageningen University and Research. It is not an official publication and the content does not represent an official position of Wageningen University and Research. III ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the result of my journey to Turkey. I decided to choose this particular topic without hesitation due to my interest in tea culture and a surprising number of its consumption. These reasons encouraged me to go back there again after the last ten years. I intended to integrate my background knowledge in marketing into the sphere of tourism to explore a new area of place studies concerning food and culture. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to many people for their support throughout seven months. First of all, I would like to thank both of my supervisors, Dr. Joost Jongerden, who patiently supervised me during my research and offered me a chance to participate in his projects. Also, Dr.