Crested Butte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

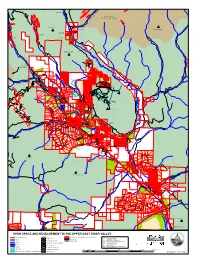

OPEN SPACE and DEVELOPMENT in the UPPER EAST RIVER VALLEY Open Space Subdivided Land & Single Family Residences Parcel Boundaries C.C

K E TO SCHOFIELD E R C R E MAROON BELLS P P SNOWMASS WILDERNESS O C GOTHIC MOUNTAIN GOTHIC TOWNSITE TEOCALLI MOUNTAIN (RMBL) Gothic Mountain Subdivision Washington Gulch (CBLT) Glee Biery C.E. Maxfield Meadows C.E. The Bench (CBLT) (CBLT) C.E. (CBLT) Rhea Easement C O U N T SNODGRASS MOUNTAIN Y 3 1 7 W E A A S S S L H T A IN T G R E T IV O E R N R I V G E U L R C The Reserve (C.E.) H R (COL) D RAGGEDS WILDERNESS Smith Hill #1 (CBLT) Divine C.E. (CBLT) Meridian Lake Park D R C I M H E T R MERIDIAN LAKE PARK O I G Gunsight D RESERVOIR I Bridge A Prospect C.A. N K Parcel CREE FUL (CBLT) L -JOY A H-BE K O E TOWN OF \( L MT. CRESTED BUTTE BLM O W N A NICHOLSON LAKE G S H L I A N K BLM G Smith Hill RanEches T ) O N Alpine Meadows C.A. G Glacier Lily U Donation L (CBLT) C Nevada C.E. H Lower Loop (CBLT) Parcels R Rolling River C.E. (CBLT) (CBLT) D Wildbird C.O. Investments Glacier Lily Estates Estates (CBLT) BLM Rice Parcel (CBLT) Peanut Mine C.E. (TCB) MT EMMONS Utley Parcel S LA (CBLT) TE Peanut Lake R Saddle Ridge C.A. Parcel (CBLT) IV ER PEANUT LAKE Gallin Parcel (CBLT) R CRESTED BUTTE D Robinson Parcel Three (CBLT) Trappers Crossing S Valleys L Kapushion Family P Confluence at C.B. -

Eric L. Clements, Ph.D. Department of History, MS2960 Southeast Missouri State University Cape Girardeau, MO 63701 (573) 651-2809 [email protected]

Eric L. Clements, Ph.D. Department of History, MS2960 Southeast Missouri State University Cape Girardeau, MO 63701 (573) 651-2809 [email protected] Education Ph.D., history, Arizona State University. Fields in modern United States, American West, and modern Europe. Dissertation: “Bust: The Social and Political Consequences of Economic Disaster in Two Arizona Mining Communities.” Dissertation director: Peter Iverson. M.A., history, with museum studies certificate, University of Delaware. B.A., history, Colorado State University. Professional Experience Professor of History, Southeast Missouri State University, Cape Girardeau Missouri, July 2009 to the present. Associate Professor of History, Southeast Missouri State University, January 2008 through June 2009. Associate Professor of History and Assistant Director of the Southeast Missouri Regional Museum, Southeast Missouri State University, July 2005 to December 2007. Assistant Professor of History and Assistant Director of the university museum, Southeast Missouri State University, August 1999 to June 2005. Education Director, Western Museum of Mining and Industry, Colorado Springs, Colorado, February 1995 through June 1999. College Courses Taught to Date Graduate: American West, Material Culture, Introduction to Public History, Progressive Era Writing Seminar, and Heritage Education. Undergraduate: American West, American Foreign Relations, Colonial-Revolutionary America, Museum Studies Survey, Museum Studies Practicum, and early and modern American history surveys. Continuing Education: “Foundations of Colorado,” a one-credit-hour course for the Teacher Enhancement Program, Colorado School of Mines, 11 and 18 July 1998. Publications Book: After the Boom in Tombstone and Jerome, Arizona: Decline in Western Resource Towns. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2003. (Reissued in paperback, 2014.) Articles and Chapters: “Forgotten Ghosts of the Southern Colorado Coal Fields: A Photo Essay” Mining History Journal 21 (2014): 84-95. -

Chapter W-9 - Wildlife Properties

07/15/2021 CHAPTER W-9 - WILDLIFE PROPERTIES Index Page ARTICLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS #900 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL WILDLIFE 1 PROPERTIES, EXCEPT STATE TRUST LANDS ARTICLE II PROPERTY SPECIFIC PROVISIONS #901 PROPERTY SPECIFIC REGULATIONS 8 ARTICLE III STATE TRUST LANDS #902 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL STATE TRUST LANDS 53 LEASED BY COLORADO PARKS AND WILDLIFE #903 PROPERTY SPECIFIC REGULATIONS 55 ARTICLE IV STATE FISH UNITS #904 REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL STATE FISH UNITS 71 #905 PROPERTY SPECIFIC REGULATIONS 72 ARTICLE V BOATING RESTRICTIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL DIVISION CONTROLLED PROPERTIES, INCLUDING STATE TRUST LANDS LEASED BY COLORADO PARKS AND WILDLIFE #906 AQUATIC NUISANCE SPECIES (ANS) 72 APPENDIX A 74 APPENDIX B 75 Basis and Purpose 81 Statement CHAPTER W-9 - WILDLIFE PROPERTIES ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS #900 - REGULATIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL WILDLIFE PROPERTIES, EXCEPT STATE TRUST LANDS A. DEFINITIONS 1. “Aircraft” means any machine or device capable of atmospheric flight, including, but not limited to, airplanes, helicopters, gliders, dirigibles, balloons, rockets, hang gliders and parachutes, and any models thereof. 2. "Water contact activities" means swimming, wading (except for the purpose of fishing), waterskiing, sail surfboarding, scuba diving, and other water-related activities which put a person in contact with the water (without regard to the clothing or equipment worn). 3. “Youth mentor hunting” means hunting by youths under 18 years of age. Youth hunters under 16 years of age shall at all times be accompanied by a mentor when hunting on youth mentor properties. A mentor must be 18 years of age or older and hold a valid hunter education certificate or be born before January 1, 1949. -

Colorado Natural Areas Program 2018- 2020 Review

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Colorado Natural Areas Program 2018- 2020 Review Triennial Report to Governor Polis 1 Pagosa skyrocket cpw.state.co.us Colorado Natural Areas Program Showcasing & protecting our state’s natural treasures since 1977 The Colorado Natural Areas Program (CNAP) is a statewide conservation program created in 1977 by the Colorado Natural Areas Act (C.R.S. 33-33). The Program is housed within Colorado Parks and Mission: Wildlife (CPW) and is advised by the Colorado Natural Areas Council To identity, evaluate, and protect specific examples of (CNAC), a seven member Governor appointed board. Program natural features and phenomena as enduring resources staff includes one full-time coordinator and one to two seasonal for present and future generations, through a statewide technicians. CNAP’s small base is supported by a contract botanist system of Designated Natural Areas. [C.R.S 33-33-102] and over 50 dedicated volunteer stewards. Table of Contents CNAP Background ......................................................................................2 Natural Features .........................................................................................3 t Natural Areas Council ...............................................................................4 Volunteer Steward Program ....................................................................5 Rare Plant Conservation ...........................................................................6 3 Year Program Highlights .......................................................................7 -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

BOLLETTINO DELLA SOCIETÀ ENTOMOLOGICA ITALIANA Non-Commercial Use Only

BOLL.ENTOMOL_150_2_cover.qxp_Layout 1 07/09/18 07:42 Pagina a Poste Italiane S.p.A. ISSN 0373-3491 Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale - 70% DCB Genova BOLLETTINO DELLA SOCIETÀ ENTOMOLOGICA only ITALIANA use Volume 150 Fascicolo II maggio-agosto 2018Non-commercial 31 agosto 2018 SOCIETÀ ENTOMOLOGICA ITALIANA via Brigata Liguria 9 Genova BOLL.ENTOMOL_150_2_cover.qxp_Layout 1 07/09/18 07:42 Pagina b SOCIETÀ ENTOMOLOGICA ITALIANA Sede di Genova, via Brigata Liguria, 9 presso il Museo Civico di Storia Naturale n Consiglio Direttivo 2018-2020 Presidente: Francesco Pennacchio Vice Presidente: Roberto Poggi Segretario: Davide Badano Amministratore/Tesoriere: Giulio Gardini Bibliotecario: Antonio Rey only Direttore delle Pubblicazioni: Pier Mauro Giachino Consiglieri: Alberto Alma, Alberto Ballerio,use Andrea Battisti, Marco A. Bologna, Achille Casale, Marco Dellacasa, Loris Galli, Gianfranco Liberti, Bruno Massa, Massimo Meregalli, Luciana Tavella, Stefano Zoia Revisori dei Conti: Enrico Gallo, Sergio Riese, Giuliano Lo Pinto Revisori dei Conti supplenti: Giovanni Tognon, Marco Terrile Non-commercial n Consulenti Editoriali PAOLO AUDISIO (Roma) - EMILIO BALLETTO (Torino) - MAURIZIO BIONDI (L’Aquila) - MARCO A. BOLOGNA (Roma) PIETRO BRANDMAYR (Cosenza) - ROMANO DALLAI (Siena) - MARCO DELLACASA (Calci, Pisa) - ERNST HEISS (Innsbruck) - MANFRED JÄCH (Wien) - FRANCO MASON (Verona) - LUIGI MASUTTI (Padova) - MASSIMO MEREGALLI (Torino) - ALESSANDRO MINELLI (Padova)- IGNACIO RIBERA (Barcelona) - JOSÉ M. SALGADO COSTAS (Leon) - VALERIO SBORDONI (Roma) - BARBARA KNOFLACH-THALER (Innsbruck) - STEFANO TURILLAZZI (Firenze) - ALBERTO ZILLI (Londra) - PETER ZWICK (Schlitz). ISSN 0373-3491 BOLLETTINO DELLA SOCIETÀ ENTOMOLOGICA ITALIANA only use Fondata nel 1869 - Eretta a Ente Morale con R. Decreto 28 Maggio 1936 Volume 150 Fascicolo II maggio-agosto 2018Non-commercial 31 agosto 2018 REGISTRATO PRESSO IL TRIBUNALE DI GENOVA AL N. -

Geology and Groun D Water Features of the Butte Valley Region Siskiyou County California

Geology and Groun d Water Features of the Butte Valley Region Siskiyou County California By P. R. WOOD GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1491 Prepared in cooperation with the California Department offf^ater Resources UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library catalog card for this publication appears after page 151. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Abstract___.__-_-____________-____________-_____----_----------- 1 Introduction.___---____-______________________--_----------------- 3 Purpose and scope of the work._..._____________________----.._-- 3 Location of area.-_-___-_____________-______--_------_--------- 4 Culture and accessibility. ________-___.___-______-----_--------- 4 Previous investigations.________-_____-______-_-_---_----------- 4 Acknowledgments _________________-___-____-__------_--------- 6 Well-numbering system____-______________-______------_------- 6 Method of investigation._____-______________-__-----_---------- 7 Physical features of the area..___________________._____-___-.---_--- 10 Topography and drainage. __________________-____----_-----_--- 10 Cascade Range.--___________-__________-_-_---_-_--------- 10 Butte Valley_-___----._-_----_---_--_---_----------------- 11 Red Rock Valley area________-_--__---_-------------------- H Oklahoma district. _____________________-___--------------- -

Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan: US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area, El Paso County, CO

Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area August 2015 CNHP’s mission is to preserve the natural diversity of life by contributing the essential scientific foundation that leads to lasting conservation of Colorado's biological wealth. Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University 1475 Campus Delivery Fort Collins, CO 80523 (970) 491-7331 Report Prepared for: United States Air Force Academy Department of Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Smith, P., S. S. Panjabi, and J. Handwerk. 2015. Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan: US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area, El Paso County, CO. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado. Front Cover: Documenting weeds at the US Air Force Academy. Photos courtesy of the Colorado Natural Heritage Program © Integrated Noxious Weed Management Plan US Air Force Academy and Farish Recreation Area El Paso County, CO Pam Smith, Susan Spackman Panjabi, and Jill Handwerk Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 August 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Various federal, state, and local laws, ordinances, orders, and policies require land managers to control noxious weeds. The purpose of this plan is to provide a guide to manage, in the most efficient and effective manner, the noxious weeds on the US Air Force Academy (Academy) and Farish Recreation Area (Farish) over the next 10 years (through 2025), in accordance with their respective integrated natural resources management plans. This plan pertains to the “natural” portions of the Academy and excludes highly developed areas, such as around buildings, recreation fields, and lawns. -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018 Designated in the original Wilderness Act of 1964, the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness covers more than 183,000 acres spanning the Gunnison and White River National Forests. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

The Western Environmental Technology Office (WETO) Butte, Montana ^Jj&Gs^ «*Sim«

DOE/EM-0217 Office of Environmental Management Office of Technology Development The Western Environmental Technology Office (WETO) Butte, Montana ^jj&gS^ «*sim« •4 4 1 Technology Summary October 1994 i DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DOCUMENrT I S UNLIMITED DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. THE WESTERN ENVIRONMENTAL TECHNOLOGY OFFICE (WETO) BUTTE, MONTANA TECHNOLOGY SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iii Introduction iv 1.0 Office of Technology Development-Sponsored Projects 1 Heavy Metals Contaminated Soil Project 1.1 Heavy-Metals-Contaminated Soil Project 3 1.2 Heavy -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

Biology and Biological Control of Dalmatian and Y Ellow T Oadflax

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Biological Control BIOLOGY AND BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF DALMATIAN AND Y ELLOW T OADFLAX LINDA M. WILSON, SHARLENE E. SING, GARY L. PIPER, RICHARD W. H ANSEN, ROSEMARIE DE CLERCK-FLOATE, DANIEL K. MACKINNON, AND CAROL BELL RANDALL Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team—Morgantown FHTET-2005-13 U.S. Department Forest September 2005 of Agriculture Service he Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (FHTET) was created in 1995 Tby the Deputy Chief for State and Private Forestry, USDA, Forest Service, to develop and deliver technologies to protect and improve the health of American forests. This book was published by FHTET as part of the technology transfer series. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/ Cover photos: Toadflax (UGA1416053)—Linda Wilson, Beetles (UGA14160033-top, UGA1416054-bottom)—Bob Richard All photographs in this publication can be accessed and viewed on-line at www.forestryimages.org, sponsored by the University of Georgia. You will find reference codes (UGA000000) in the captions for each figure in this publication. To access them, point your browser at http://www.forestryimages.org, and enter the reference code at the search prompt. How to cite this publication: Wilson, L. M., S. E. Sing, G. L. Piper, R. W. Hansen, R. De Clerck- Floate, D. K. MacKinnon, and C. Randall. 2005. Biology and Biological Control of Dalmatian and Yellow Toadflax. USDA Forest Service, FHTET-05-13. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status.