Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Coverage Determination for Respiratory Therapy

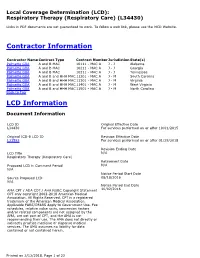

Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Respiratory Therapy (Respiratory Care) (L34430) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information Contractor Name Contract Type Contract Number Jurisdiction State(s) Palmetto GBA A and B MAC 10111 - MAC A J - J Alabama Palmetto GBA A and B MAC 10211 - MAC A J - J Georgia Palmetto GBA A and B MAC 10311 - MAC A J - J Tennessee Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11201 - MAC A J - M South Carolina Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11301 - MAC A J - M Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11401 - MAC A J - M West Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11501 - MAC A J - M North Carolina Back to Top LCD Information Document Information LCD ID Original Effective Date L34430 For services performed on or after 10/01/2015 Original ICD-9 LCD ID Revision Effective Date L31593 For services performed on or after 01/29/2018 Revision Ending Date LCD Title N/A Respiratory Therapy (Respiratory Care) Retirement Date Proposed LCD in Comment Period N/A N/A Notice Period Start Date Source Proposed LCD 08/18/2016 N/A Notice Period End Date AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement 10/02/2016 CPT only copyright 2002-2018 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. Applicable FARS/DFARS Apply to Government Use. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors and/or related components are not assigned by the AMA, are not part of CPT, and the AMA is not recommending their use. -

Nebulizers: Diagnosis Codes – Medicare Advantage Policy Appendix

UnitedHealthcare® Medicare Advantage Policy Appendix: Applicable Code List Nebulizers: Diagnosis Codes This list of codes applies to the Medicare Advantage Policy Guideline titled Approval Date: September 8, 2021 Nebulizers. Applicable Codes The following list(s) of procedure and/or diagnosis codes is provided for reference purposes only and may not be all inclusive. The listing of a code does not imply that the service described by the code is a covered or non-covered health service. Benefit coverage for health services is determined by the member specific benefit plan document and applicable laws that may require coverage for a specific service. The inclusion of a code does not imply any right to reimbursement or guarantee claim payment. Other Policies and Guidelines may apply. Diagnosis Code Description For HCPCS Codes A7003, A7004, and E0570 A15.0 Tuberculosis of lung A22.1 Pulmonary anthrax A37.01 Whooping cough due to Bordetella pertussis with pneumonia A37.11 Whooping cough due to Bordetella parapertussis with pneumonia A37.81 Whooping cough due to other Bordetella species with pneumonia A37.91 Whooping cough, unspecified species with pneumonia A48.1 Legionnaires' disease B20 Human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease B25.0 Cytomegaloviral pneumonitis B44.0 Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis B59 Pneumocystosis B77.81 Ascariasis pneumonia E84.0 Cystic fibrosis with pulmonary manifestations J09.X1 Influenza due to identified novel influenza A virus with pneumonia J09.X2 Influenza due to identified novel influenza A virus with other -

Statistical Analysis Plan

Non-Interventional Study Protocol Study Code << DXXXRXXX >> Version V1.4 Date 14 July 2017 Decline In lung-function Among Patients with chronic obstructive Lung disease On maintenance therapy (DIAPLO) An observational study evaluating the benefits of early intervention with maintenance therapies to prevent or slow down rapid lung function decline in patients who are at high risk at the time of COPD diagnosis in the combined Optimum Patient Care Research Database and Clinical Practice Research Datalink databases TITLE PAGE Non-Interventional Study Protocol Study Code << DXXXRXXX >> Version 14 July 2017 Date 14 July 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TITLE PAGE ........................................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................... 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................. 5 RESPONSIBLE PARTIES ...................................................................................... 6 PROTOCOL SYNOPSIS DIAPLO STUDY ........................................................... 7 AMENDMENT HISTORY ................................................................................... 12 MILESTONES ....................................................................................................... 13 1. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE .................................................................. 14 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................... -

Medicare Approved Six Minute Walk Diagnosis Codes

MEDICARE APPROVED DIAGNOSIS CODES FOR SIX MINUTE WALK TESTING ICD-10 Codes that Support Medical Necessity Group 1 Codes: ICD-10 CODE DESCRIPTION B44.81 Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis C33 Malignant neoplasm of trachea C34.00 Malignant neoplasm of unspecified main bronchus C34.01 Malignant neoplasm of right main bronchus C34.02 Malignant neoplasm of left main bronchus C34.10 Malignant neoplasm of upper lobe, unspecified bronchus or lung C34.11 Malignant neoplasm of upper lobe, right bronchus or lung C34.12 Malignant neoplasm of upper lobe, left bronchus or lung C34.2 Malignant neoplasm of middle lobe, bronchus or lung C34.30 Malignant neoplasm of lower lobe, unspecified bronchus or lung C34.31 Malignant neoplasm of lower lobe, right bronchus or lung C34.32 Malignant neoplasm of lower lobe, left bronchus or lung C34.80 Malignant neoplasm of overlapping sites of unspecified bronchus and lung C34.81 Malignant neoplasm of overlapping sites of right bronchus and lung C34.82 Malignant neoplasm of overlapping sites of left bronchus and lung C34.90 Malignant neoplasm of unspecified part of unspecified bronchus or lung C34.91 Malignant neoplasm of unspecified part of right bronchus or lung C34.92 Malignant neoplasm of unspecified part of left bronchus or lung C78.00 Secondary malignant neoplasm of unspecified lung C78.01 Secondary malignant neoplasm of right lung C78.02 Secondary malignant neoplasm of left lung C78.30 Secondary malignant neoplasm of unspecified respiratory organ C78.39 Secondary malignant neoplasm of other respiratory organs -

Various Types of Pneumoconiosis

Pneumoconiosis MEANING Pneumoconiosis is a chronic lung disease caused due to the inhalation of various forms of dust particles, particularly in industrial workplaces, for an extended period of time. Hence it is also said to be an occupational lung disease, which are a particular subdivision of occupational related diseases that are related primarily to being exposed to harmful substances, whether they are gas or dusts, in the work place, and the pulmonary disorders that may result from it. The severity and type of pneumoconiosis depends on what the dust particles comprise of; for example, small amounts of certain substances, such as asbestos and silica, can lead to serious reactions, while others may not be as harmfulCoalworker's pneumoconiosis Various Types of Pneumoconiosis • The most common types of pneumoconiosis are: • coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, silicosis, • asbestosis. As is evident by their names, these pneumoconioses are caused due to the inhalation of coal mine dust, silica dust, and asbestos fibers. Usually, it takes several years for these pneumoconioses to develop and manifest themselves. However, sometimes, particularly with silicosis, it can develop quite rapidly, within a short period of being exposed to large amounts of silica dust. In their severe form, pneumoconioses often result in the impairment of the lungs, disability, and even untimely death. Asbestosis: This is caused due to the inhalation of fibrous minerals that asbestos is made of. The exposure begins with the baggers, who handle the asbestos by collecting them and packaging them, to workers that make products out of them such as insulation material, cement, and tiles, and people working in the shipbuilding industry, and construction workers. -

Interstitial &Infiltrative Pulmonary Diseases

A 55 year old man comes for evaluation of exercise intolerance over the past 6 months. He has no significant past medical history. He informs you that over the past week he can not walk across the room without getting ―short of breath.‖ He takes no medications and has never smoked. The physical exam is significant for a respiratory rate of 24/minute, jugular venous distension 8 cm, coarse crackles on auscultation, clubbing, and trace pedal edema on the legs. The chest x-ray reveals diffuse reticular disease. What is the diagnosis? Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Prof. Mutti Ullah Khan Head of Department Medical Unit-II Holy Family Hospital Rawalpindi Medical College Definition. Classification. Features common to all DPLDs (clinical manifestations, physical findings, workup). Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Occupational Lung Diseases/ Pneumoconiosis A heterogeneous group of conditions affecting the pulmonary parenchyma (interstitium) and/or alveolar lumen, which are frequently considered collectively as they share a sufficient number of clinical, physiological and radiographic similarities. CLINICAL PRESENTATION: Cough: usually dry, persistent and distressing Breathlessness: usually slowly progressive; insidious onset; acute in some cases EXAMINATION FINDINGS: Crackles: typically bilateral and basal. Clubbing: common in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but also seen in other types, e.g. asbestosis. Central cyanosis and signs of right heart failure in advanced disease. Laboratory investigations Full blood count: lymphopenia in sarcoid; eosinophilia in pulmonary eosinophilias and drug reactions; neutrophilia in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Ca2+: may be elevated in sarcoid. Lactate dehydrogenase: may be elevated in active alveolitis. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme: non- specific indicator of disease activity in sarcoid. -

The Timing of Onset of Symptoms in People with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: a UK General Population-Based Case-Control Study – Supplementary Material

The timing of onset of symptoms in people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a UK general population-based case-control study – Supplementary material Thomas Hewson, BMedSci Tricia M McKeever, PhD Jack E Gibson, PhD Vidya Navaratnam, PhD Richard B Hubbard, DM John P Hutchinson, BMBS - Summary of patient population and Consort diagram of numbers of exclusions - Additional tables and figures for cough, consultations for heart failure, consultations for COPD, sensitivity analyses - Read codes for exclusions Summary of patient population Cases Controls n (%) n (%) Sex Male 1,301 (63.1) 4,580 (63.7) Female 761 (36.9) 2,607 (36.3) Age group <55 years 87 (4.2) 277 (3.9) 55-64 years 234 (11.4) 803 (11.2) 65-74 years 638 (30.9) 2,227 (31.0) 75-84 years 803 (38.9) 2,864 (39.9) >84 years 300 (14.6) 1,016 (14.1) Smoking category* Current 348 (18.3) 1,158 (18.2) Ex 810 (42.5) 1,923 (30.3) Never 746 (39.2) 3,269 (51.5) *based on latest record of smoking status prior to diagnosis A Consort diagram of patient selection is shown below. Controls were identified as a 4:1 incidence density sample, matched on age (year of age rather than age-band), sex and GP practice. Each case could have up to four possible controls. Consort diagram of patient selection 13,906 patients from THIN 2,801 cases 11,105 controls 1,415 patients excluded with inadequate length of data pre-diagnosis (already applied to cases 12,491 patients when selected) 2,801 cases 9,690 controls 96 patients excluded aged 40 or below 12,395 patients 2,774 cases 9,621 controls 153 cases excluded -

Medical Policy

Medical Policy Nebulizers/Compressors Description A nebulizer is used to produce a fine mist that is delivered to the respiratory system. Policy A small volume nebulizer (A7003, A7004, A7005), related compressor (E0570) and FDA-approved inhalation solutions of the drugs listed below are covered when: a. It is reasonable and necessary to administer albuterol (J7611, J7613), arformoterol (J7605), budesonide (J7626), cromolyn (J7631), formoterol (J7606), ipratropium (J7644), levalbuterol (J7612, J7614), or metaproterenol (J7669) for the management of obstructive pulmonary disease (Reference the Diagnosis Codes that Support Medical Necessity Group 8 Codes section for applicable diagnoses); or b. It is reasonable and necessary to administer dornase alpha (J7639) to a member with cystic fibrosis (Reference the Diagnosis Codes that Support Medical Necessity Group 9 Codes section for applicable diagnoses); or c. It is reasonable and necessary to administer tobramycin (J7682) to a member with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis (Reference the Diagnosis Codes that Support Medical Necessity Group 10 Codes section for applicable diagnoses); or d. It is reasonable and necessary to administer pentamidine (J2545) to a member with HIV, pneumocystosis, or complications of organ transplants (Reference the Diagnosis Codes that Support Medical Necessity Group 4 Codes section for applicable diagnoses); or e. It is reasonable and necessary to administer acetylcysteine (J7608) for persistent thick or tenacious pulmonary secretions (Reference the Diagnosis Codes that Support Medical Necessity Group 7 Codes section for applicable diagnoses). Compounded inhalation solutions (J7604, J7607, J7609, J7610, J7615, J7622, J7624, J7627, J7628, J7629, J7632, J7634, J7635, J7636, J7637, J7638, J7640, J7641, J7642, J7643, J7645, J7647, J7650, J7657, J7660, J7667, J7670, J7676, J7680, J7681, J7683, J7684, J7685, and compounded solutions billed with J7699) will be denied as not reasonable and necessary. -

2012/061811 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date ¾ 10 May 2012 (10.05.2012) 2012/061811 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 39/395 (2006.01) C07K 16/22 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61P 11/00 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US201 1/059589 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 7 November 20 11 (07.1 1.201 1) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, (25) Filing Language: English RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (26) Publication Language: English TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 61/456,370 5 November 2010 (05.1 1.2010) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): FIBRO¬ GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, GEN, INC. -

Haemosiderosis (Silico-Siderosis)

XVI. Diseases Of The Respiratory System 194 Haemosiderosis (silico-siderosis) II-6.94 Lung: Is enlarged Diffusely-fibrotic: Rusty-red (iron-deposition) Pleura Is thickened N.B.I: Fibrosis, here, is more diffusing than nodular. The lesion is more in the upper half of the lung. The Prussian blue reaction for iron is positive in the brown-brick-red fibrosed areas. N.B. 2: Other types of dust diseases 1) Beryllium Pneumonitis: In those working with fluorescent lamps berylliosis. Acute pneumonitis: o A diffuse infiltration of lungs with oedema and haemorrhage; o (No polymorphs; only plasma cells). Delayed poisoning: o Chronic granulomatous lesions, the condition has to be differentiated from: . Miliary tuberculosis. Sarcoidosis. 2) Byssinosis: It is inhalation of cotton fibres little effect. 3) Bauxite fibrosis (Shaver's disease): Is caused by silica with aluminum. 4) Baggastosis: Is inhalation of cane-sugar fibres little effect. Emphysema (chronic, obstructive = so-called hypertrophic) Lung Voluminous (hence the old term "hypertrophic”). Is pale especially at: Apex Free borders Crackles and pits on pressure Shows multiple bullae Cut surface: Is swollen in many parts Dry as a meshwork (spongy structure) Semi translucent Shows: Bullae Anthracotic areas Bullae and vesicles: Appear mainly at : Apex Free borders Anterior margin Spaces (empty except for air) Are multiple (numerous) Variable in size and in shape Thin-walled Feathery Bloodless Paler than the remaining lung tissue N.B. 1 Emphysema may be classified into: 1. Acute: Vesicular (compensatory in origin). Interstitial (traumatic in origin). 2. Chronic: A) Generalized obstructive (so-called hypertrophic), due to loss of (or deficiency in) the elastic tissue of the lung and increase in the residual air content and the air trapped in the lung will inflate it. -

Clinical Medical Policy

CLINICAL MEDICAL POLICY Policy Name: Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) Policy Number: MP-037-MC-ALL Responsible Department(s): Medical Management Provider Notice Date: 06/15/2018; 11/01/2017 Issue Date: 07/15/2018; 12/01/2017 Effective Date: 07/15/2018; 12/01/2017 Annual Approval Date: 04/18/2019 Revision Date: 04/18/2018 Products: North Carolina Medicare Assured All participating and nonparticipating hospitals and Application: providers Page Number(s): 1 of 11 DISCLAIMER Gateway Health℠ (Gateway) medical policy is intended to serve only as a general reference resource regarding coverage for the services described. This policy does not constitute medical advice and is not intended to govern or otherwise influence medical decisions. POLICY STATEMENT Gateway Health℠ may provide coverage under the medical-surgical benefits of the Company’s Medicare products for medically necessary pulmonary rehabilitation. This policy is designed to address medical necessity guidelines that are appropriate for the majority of individuals with a particular disease, illness or condition. Each person’s unique clinical circumstances warrant individual consideration, based upon review of applicable medical records. Policy No. MP-037-MC-ALL Page 1 of 11 DEFINITIONS Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) – A multi-disciplinary program of care for patients with chronic respiratory impairment who are symptomatic and often have decreased daily life activities. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) – A common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases. The chronic airflow limitation that is characteristic of COPD is caused by a mixture of small airways disease (e.g., obstructive bronchiolitis) and parenchymal destruction (emphysema), the relative contributions of which vary from person to person. -

Respiratory Therapy) (A57225)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Respiratory Care (Respiratory Therapy) (A57225) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT NUMBER JURISDICTION STATE(S) Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02101 - MAC A 02101 - MAC A J - F Alaska Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02102 - MAC B 02102 - MAC B J - F Alaska Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02201 - MAC A 02201 - MAC A J - F Idaho Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02202 - MAC B 02202 - MAC B J - F Idaho Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02301 - MAC A 02301 - MAC A J - F Oregon Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02302 - MAC B 02302 - MAC B J - F Oregon Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02401 - MAC A 02401 - MAC A J - F Washington Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 02402 - MAC B 02402 - MAC B J - F Washington Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 03101 - MAC A 03101 - MAC A J - F Arizona Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 03102 - MAC B 03102 - MAC B J - F Arizona Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 03201 - MAC A 03201 - MAC A J - F Montana Created on 03/01/2021. Page 1 of 35 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT NUMBER JURISDICTION STATE(S) Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 03202 - MAC B 03202 - MAC B J - F Montana Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 03301 - MAC A 03301 - MAC A J - F North Dakota Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 03302 - MAC B 03302 - MAC B J - F North Dakota Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC 03401 - MAC A 03401 - MAC A J - F South Dakota Noridian