Chapter Seven Hard-Headed Spirituality and Soft-Hearted Piety: the Redemptorists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Submission in Response To

Submission from the Truth Justice and Healing Council Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Issues Paper No.7 | Statutory Victims of Crime Compensation Schemes 2 October 2014 PO Box 4593 KINGSTON ACT 2604 T 02 6234 0900 F 02 6234 0999 E [email protected] W www.tjhcouncil.org.au Justice Peter McClellan AM Chair Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Via email: [email protected] Dear Justice McClellan As you know, the Truth Justice and Healing Council (the Council) has been appointed by the Catholic Church in Australia to oversee the Church’s response to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (the Royal Commission). We now provide the Council’s submission in response to the Royal Commission’s Issues Paper 7 – Statutory Victims of Crime Compensation Schemes. Yours sincerely Neville Owen Chair Truth Justice and Healing Council 2 October 2014 Our Commitment The leaders of the Catholic Church in Australia recognise and acknowledge the devastating harm caused to people by the crime of child sexual abuse. We take this opportunity to state: Sexual abuse of a child by a priest or religious is a crime under Australian law and under canon law. Sexual abuse of a child by any Church personnel, whenever it occurred, was then and is now indefensible. That such abuse has occurred at all, and the extent to which it has occurred, are facts of which the whole Church in Australia is deeply ashamed. The Church fully and unreservedly acknowledges the devastating, deep and ongoing impact of sexual abuse on the lives of the victims and their families. -

From the Acorn to the Oak. the Acorn Was Planted on Fertile Ground

From the Acorn to the Oak Celebrating the Brigidine Story Rita Minehan csb 1 Introduction I was invited to share the Brigidine Story “From the Acorn to the Oak” with the Brigidine Sisters in the Irish-UK Province in July 2006, in preparation for the Brigidine Bicentenary in 2007. This was the beginning of “a world tour” with the story. I’ve been privileged to share it with the Sisters and Associates in the US Region, and the Sisters and their co- workers in the Victorian and New South Wales Provinces in Australia. A shorter version of the story has been shared in parishes in Tullow, Mountrath, Abbeyleix, Paulstown, Kildare, Ballyboden, Finglas, Denbigh and Slough. The story was slightly adapted to include a little local history in each location. The story has been shared with teachers and students in Denbigh, Wales; in Indooroopilly, Queensland; in St Ives, NSW; in Killester and Mentone, Victoria. A great number of people around the world have been drawn into the Brigidine Story over the past two hundred years. Sharing the story during the bicentenary year was a very meaningful and enriching experience. Rita Minehan csb Finglas, Dublin 2009 Acknowledgements I would like to express gratitude to Sr. Maree Marsh, Congregational Leader, for encouragement to print this booklet and for her work on layout and presentation. I want to thank Sr. Theresa Kilmurray for typing the script, Ann O’Shea for her very apt line drawings and Srs. Anne Phibbs and Patricia Mulhall for their editorial advice. Cover photo taken by Brendan Kealy. 2 Celebrating the Brigidine Story Table of Contents Chapter 1. -

Annual Report 2019 Annual Report 2018-19

33 ANNUAL REPORTREPORT 20120189 -19 CATHOLIC RELIGIOUS AUSTRALIA Lv 1, 9 Mount Street, North Sydney NSW 2060 Ph: +612 9557 2695 www.catholicreligious.org.au 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PRESIDENT’S REPORT 3 2. NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT 5 3. GOVERNANCE 9 4. SNAPSHOT 13 5. HIGHLIGHTS 14 6. PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS 15 7. CRA COMMITTEE REPORTS 18 8. AROUND THE STATES 24 9. REPORT FROM ACRATH 26 10. ENTITIES ON WHICH CRA IS REPRESENTED 27 11. REPORTS FROM CRA REPRESENTATIVES APPOINTED TO EXTERNAL 28 BODIES 12. CRA RELATIONSHIPS 33 3 1. PRESIDENT’S REPORT As we gather for this National Assembly in 2019, we recall the gifts and challenges that have been ours during this past twelve months. At our Assembly in 2018 we launched the new National CRA structure. The CRA Council was entrusted to carry forward the vision of this reality across Australia. This was an exciting opportunity in which to be involved. It required both delighting in the birthing of the new and at the same time engaging with the experience of transition. Of significance has been the establishment of the CRA committees, the State networking bodies and the work of the CRA council as well as the development of the secretariat. There is much to celebrate and appreciate in what has been achieved. During these days of the Assembly, the Council will shall share with you the next phase of the implementation of this National CRA structure. Embracing the Vision of the National CRA Structure At the heart of this vision has been our on-going commitment to participation in the mission of God. -

To Download the Congregations List

Prayers for Peace November 3, 2020 Election Day Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Carmelite Sisters Hamden, CT Reno, Nevada Benedictine Sisters Mother of God Monastery Claretian Missionary Sisters, Watertown, SD Miami, FL Benedictine Sisters Comboni Missionary Sisters of Baltimore Congregation de Notre Dame Benedictine Sisters in US of Brerne, Texas Congregation of Divine Providence Benedictine Sisters Congregation of Notre Dame of Cullman Alabama Blessed Sacrament Province Benedictine Sisters Congregation of Sisters of St Agnes of Elizabeth , NJ Congregation of St Joseph Benedictine Sisters Cleveland, OH of Erie, PA Benedictine Sisters Congregation of the Holy Cross of Newark, DE Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Family Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, of Naareth Clyde, MO Congregation of the Humility of Mary Benedictine Sisters Davenport, Iowa of Pittsburgh Consolata Missionary Sisters Benedictine Sisters of St Paul's Monastery of Belmont, MI St Paul, MN Daughters of Charity Benedictine Sisters USA of Virginia Daughters of Mary and Joseph California Benedtictines at Benet Hill Monastery Daughters of the Charity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Bernadine Franciscan Sisters USA delegation Brigidine Sisters Daughters of the Heart of Mary San Antonio, TX US Province Carmelite Sisters of Charity Daughters of Wisdom Vedruna Dominican Sisters of Adrian, MI 1 Prayers for Peace November 3, 2020 Election Day Dominican Sisters Little Company of Mary Sisters of Caldwell, NJ USA Dominican Sisters of Mission Little Sisters of the -

Grants Awarded Winter

GRANTS AWARDED: Winter 2019 Country State/Province Congregation Applicant Funding Priority Project Title INTERNATIONAL Alternative Energy/Communication Infrastructure Empowering Women, Youth and Girl Child with India Tamil Nadu Medical Sisters of St. Joseph Queen Mary convent and Health Center Sustainable Living Kenya Eastern Religious of the Assumption Holy Spirit Catholic Primary and Secondary School Solar for water pump and Internet installation Federal Capital Nigeria Territory Society of the Holy Child Jesus Cornelian Maternity and Rural Healthcare Center Solar Energy Lighting System Anti-Trafficking Congregation of Our Lady of Charity of the Argentina Jujuy Good Shepherd Hogar de la Joven Living in Freedom: A stop to human trafficking Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of India Goa Mary National Domestic Workers Movement - Goa Protection of women and children from trafficking India Nagaland Ursuline Franciscan Congregation Assisi Center for Integrated Develpment Combating Trafficking Through Sensitization Program Nigeria Delta Sisters of the Eucharistic Heart of Jesus Vitalis Development and Peace Centre Vitalis Development and Peace Centre Clean Water/Food/Agriculture Brazil Sao Paulo Sisters of the Holy Cross Projeto Sol Projeto Sol Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross of Cameroon Centre Chavanod Elig Mfomo Water Project Water facility Cameroon Est Sisters of St. Joseph of Cluny Kaigama Farm-School Extension Hens House and Extension Apiary Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul Colombia Risaralda Obra Social Santa Luisa de Marillac Centro Social Santa Luisa Marillac Congo, Democratic Republic of Nord-Kivu Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul of Lendelede Women Farmers of Keshero Rabbit farming Misioneras de los Sagrados Corazones de Jesus Guatemala Jalapa y Maria Mujeres Unidas por un Futuro Mejor Family Orchards for a better future Dominican Sisters of Our Lady of the Rosary of Haiti Centre Monteils Los Cacaos Agricultural Formation Center Los Cacaos, Haiti, Irrigation Farming Initiative India Andhra Pradesh Sisters of St. -

The Brigidine Sisters

Review of Child Safeguarding Practice – The Brigidine Sisters Review of Child Safeguarding Practice in the religious congregation of The Sisters of Saint Brigid (The Brigidine Sisters) undertaken by The National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church in Ireland (NBSCCCI) Date: May 2015 Page 1 of 17 Review of Child Safeguarding Practice – The Brigidine Sisters CONTENTS Page Background 3 Introduction 4 Role Profile 4 Profile of Members 5 Policy and Procedures Document 5 Structures 6 Management of Allegations 7 Conclusion 7 Terms of Reference 8 Page 2 of 17 Review of Child Safeguarding Practice – The Brigidine Sisters Background The National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church in Ireland (NBSCCCI) was asked by the Sponsoring Bodies, namely the Irish Episcopal Conference, the Conference of Religious of Ireland and the Irish Missionary Union, to undertake a comprehensive review of safeguarding practice within and across all the Church authorities on the island of Ireland. The NBSCCCI is aware that some religious congregations have ministries that involve direct contact with children while others do not. In religious congregations that have direct involvement with children, reviews of Child Safeguarding have been undertaken by measuring their practice compliance against all seven Church Standards. Where a religious congregation no longer has, or never had ministry involving children, and has not received any allegation of sexual abuse the NBSCCCI reviews are conducted using a shorter procedure. The size, age and activity profiles of religious congregations can vary significantly, and the NBSCCCI accepts that it is rational that the form of review be tailored to the profile of each Church Authority, where the ministry with children is limited or non- existent. -

An Historical Analysis of the Contribution of Two Women's

They did what they were asked to do: An historical analysis of the contribution of two women’s religious institutes within the educational and social development of the city of Ballarat, with particular reference to the period 1950-1980. Submitted by Heather O’Connor, T.P.T.C, B. Arts, M.Ed Studies. A thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of PhD. School of Arts and Social Sciences (NSW) Faculty of Arts and Sciences Australian Catholic University November, 2010 Statement of sources This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics/Safety Committees. i ABSTRACT This thesis covers the period 1950-1980, chosen for the significance of two major events which affected the apostolic lives of the women religious under study: the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), and the progressive introduction of state aid to Catholic schools, culminating in the policies of the Whitlam government (1972-1975) which entrenched bi- partisan political commitment to funding non-government schools. It also represents the period during which governments of all persuasions became more involved in the operations of non-government agencies, which directly impacted on services provided by the churches and the women religious under study, not least by imposing strict conditions of accountability for funding. -

130 Years of Brigidine Life and Ministry in Ararat

130 YEARS OF BRIGIDINE LIFE AND MINISTRY IN ARARAT This year marks one hundred and thirty years since the first Brigidine Sisters arrived in Ararat on November 14, 1888. Earlier in that year, Bishop Moore of Ballarat recruited a small group of Sisters to help with education in Ararat. The pioneer Sisters who generously volunteered to form the Ararat community and serve the people in that town were from two convents in Ireland. Three came from the Abbeyleix community (Mothers Gertrude Kelly, Josephine Clancy and Paul Barron) and two from the Goresbridge community (Mother Cecilia Synnott and Sister Mary Malachy Byrne). In mid-September 1888, they sailed on the SS Ormuz (right) from London along with six Nazareth Sisters, Redemptorist Priests, Holy Ghost Fathers and some Diocesan priests all destined for the Ballarat Diocese. The Loreto Sisters offered hospitality for the Sisters for a few days in Ballarat. The Sisters then travelled to Ararat and their first home was in the presbytery graciously given over by Fr Meade (pictured below with Foundation Sisters) until the convent was built Schools began the following year offering a wide variety of subjects. Times were hard and they were a long way from home but the generosity of the Parish Priest and the people was amazing and greatly helped them settle in. The Convent was built and school rooms extended as student numbers grew. At the same time many young women came from a wide area of Western Victoria wanting to join the Sisters. By 1900 the community numbered twenty sisters. In 1900, a small group of Sisters went from Ararat to begin a new community in Maryborough and later in 1920, another group went to Horsham. -

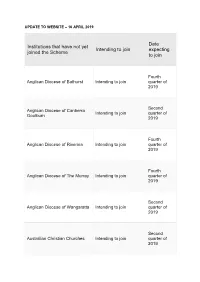

Institutions That Have Not Yet Joined the Scheme Intending to Join Date

UPDATE TO WEBSITE – 16 APRIL 2019 Date Institutions that have not yet Intending to join expecting joined the Scheme to join Fourth Anglican Diocese of Bathurst Intending to join quarter of 2019 Second Anglican Diocese of Canberra Intending to join quarter of Goulburn 2019 Fourth Anglican Diocese of Riverina Intending to join quarter of 2019 Fourth Anglican Diocese of The Murray Intending to join quarter of 2019 Second Anglican Diocese of Wangaratta Intending to join quarter of 2019 Second Australian Christian Churches Intending to join quarter of 2019 Date Institutions that have not yet Intending to join expecting joined the Scheme to join Australian Institute of Music Intending to join Australian Indigenous Ministries Third quarter Baptists NT Intending to join of 2019 Second Baptists QLD Intending to join quarter of 2019 Second Barnardos Australia Intending to join quarter of 2019 Brisbane Grammar Catholic - Augustinians – Order Intending to join of Saint Augustine Date Institutions that have not yet Intending to join expecting joined the Scheme to join Third quarter Catholic - Australian Ursulines Intending to join of 2019 Catholic - Benedictine Intending to join Community of New Norcia Second Catholic - Blessed Sacrament Intending to join quarter of Fathers 2020 Second Catholic - Brigidine Sisters Intending to join quarter of 2019 Catholic - Capuchin Franciscan Third quarter Intending to join Friars of 2019 Catholic - Columban Fathers – Intending to join St Columban’s Mission Society Catholic - Cistercian Monks Date Institutions that -

Catholic Religious Institutes in Australia 22 September 2020

Catholic Religious Institutes in Australia 22 September 2020 Australian Catholic Bishops Conference National Centre for Pastoral Research Catholic Religious Institutes in Australia The 2018 Survey of Religious Congregations Dr Trudy Dantis In association with 22 September 2020 [email protected] 1 www.ncpr.catholic.org.au 22 September 2020 [email protected] 2 ACBC National Centre for Pastoral Research 1 Catholic Religious Institutes in Australia 22 September 2020 See, I am Doing a New Thing! - 2009 Survey of Religious Congregations in Australia Understanding - 2019 Religious Vocation in Australia Today - 2018 Available at ncpr.catholic.org.au 22 September 2020 [email protected] 3 Demographics ACBC National Centre for Pastoral Research 2 Catholic Religious Institutes in Australia 22 September 2020 Catholic Religious in Australia Membership: 1948-2020 Religious Sisters Religious Brothers Clerical Religious 14,000 12,000 10,000 8,000 persons of 6,000 Number 4,000 2,000 0 1948 1952 1956 1960 1964 1968 1972 1976 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020 Year Source: The Official Directory of the Catholic Church in Australia – annual or biennial editions from 1948 to 2020. 22 September 2020 [email protected] 5 Total membership as at 1 January 2018 Total membership Number Religious sisters 6,018 Religious brothers 637 Clerical orders 1,505 Institutes 46 Societies 153 Associations 72 Total 8,431 Source: 2018 Survey of Religious Congregations in Australia, Australian Catholic Bishops Conference -

Institutions That Have Joined the Scheme

Institutions that have joined the Scheme Institutions must agree to join the National Redress Scheme so they can provide redress to people who experienced child sexual abuse in relation to their institution. All state and territory governments as well as the Commonwealth have joined the Scheme, and legislation is in place in all states and territories to enable non-government institutions to join the Scheme. Many other non-government institutions have committed to joining the Scheme, including the Catholic Church, the Anglican Church, the Uniting Church, the Salvation Army, the YMCA and Scouts Australia. For non-government institutions, the process of joining the Scheme includes several steps. This means there may be a delay between the time that an institution announces it will join the Scheme, and the time that applications relating to those institutions can be processed. The Scheme is working very closely with institutions to help them join as quickly as possible. Institutions must provide a list of their current and historic physical locations. For some large and longstanding institutions the list can be extensive. Institutions must also establish that they are operationally ready. This involves confirming how they will structure themselves, resolving to participate, completing training provided by the Department of Social Services, and demonstrating their capacity to pay for redress and to deliver direct personal responses. You can make an application for redress at any time, but applications cannot be assessed until the responsible institution, or institutions, have fully joined the Scheme. They need to complete all the necessary steps. Once you have made an application, the National Redress Scheme will contact you to acknowledge receipt of the application and provide initial guidance on the process. -

Civil Litigation

Submission from the Truth Justice and Healing Council Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Issues Paper No. 5 Civil Litigation 15 April 2014 PO Box 4593 KINGSTON ACT 2604 T 02 6234 0900 F 02 6234 0999 E [email protected] W www.tjhcouncil.org.au Justice Peter McClellan AM Chair Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Via email: [email protected] Dear Justice McClellan As you know, the Truth Justice and Healing Council (the Council) has been appointed by the Catholic Church in Australia to oversee the Church’s response to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (the Royal Commission). We now submit the Council’s submission in response to the Royal Commission’s Issues Paper 5 – Civil Litigation. Yours sincerely Francis Sullivan Chief Executive Officer Truth Justice and Healing Council 15 April 2014 Our Commitment The leaders of the Catholic Church in Australia recognise and acknowledge the devastating harm caused to people by the crime of child sexual abuse. We take this opportunity to state: Sexual abuse of a child by a priest or religious is a crime under Australian law and under canon law. Sexual abuse of a child by any Church personnel, whenever it occurred, was then and is now indefensible. That such abuse has occurred at all, and the extent to which it has occurred, are facts of which the whole Church in Australia is deeply ashamed. The Church fully and unreservedly acknowledges the devastating, deep and ongoing impact of sexual abuse on the lives of the victims and their families.