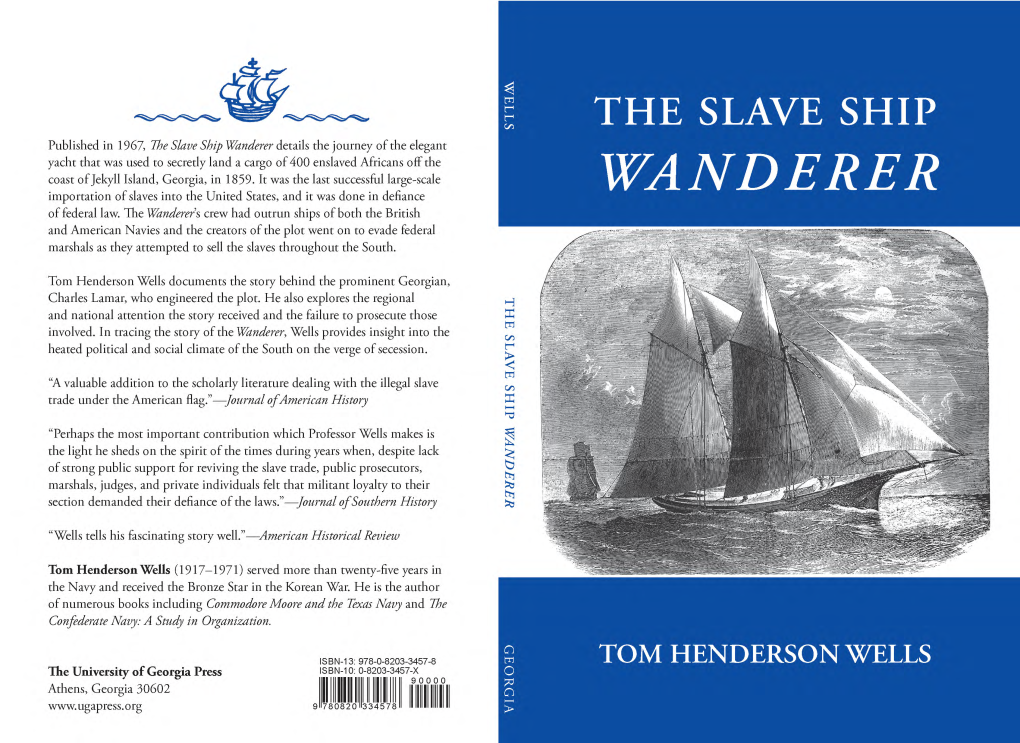

The Slave Ship Wanderer. 107 P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A General Model of Illicit Market Suppression A

ALL THE SHIPS THAT NEVER SAILED: A GENERAL MODEL OF ILLICIT MARKET SUPPRESSION A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government. By David Joseph Blair, M.P.P. Washington, DC September 15, 2014 Copyright 2014 by David Joseph Blair. All Rights Reserved. The views expressed in this dissertation do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. ii ALL THE SHIPS THAT NEVER SAILED: A GENERAL MODEL OF TRANSNATIONAL ILLICIT MARKET SUPPRESSION David Joseph Blair, M.P.P. Thesis Advisor: Daniel L. Byman, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This model predicts progress in transnational illicit market suppression campaigns by comparing the relative efficiency and support of the suppression regime vis-à-vis the targeted illicit market. Focusing on competitive adaptive processes, this ‘Boxer’ model theorizes that these campaigns proceed cyclically, with the illicit market expressing itself through a clandestine business model, and the suppression regime attempting to identify and disrupt this model. Success in disruption causes the illicit network to ‘reboot’ and repeat the cycle. If the suppression network is quick enough to continually impose these ‘rebooting’ costs on the illicit network, and robust enough to endure long enough to reshape the path dependencies that underwrite the illicit market, it will prevail. Two scripts put this model into practice. The organizational script uses two variables, efficiency and support, to predict organizational evolution in response to competitive pressures. -

The Porsche Type List

The Porsche Type List When Professor Ferdinand Porsche started his business, the company established a numeric record of projects known as the Type List. As has been reported many times in the past, the list began with Type 7 so that Wanderer-Werke AG did not realize they were the company’s first customer. Of course, as a result, Porsche’s famous car, the 356 as defined on the Type List, was actually Porsche’s 350th design project. In reviewing the Porsche Type List enclosed on this website, you might notice several interesting aspects. First, although there is a strong chronological alignment of Type numbers, it is certainly not perfect. No official explanation exists as to why this occurs. It is possible that Type numbers were originally treated only as an informal configuration and data management tool and today’s rigorous examination of Porsche history is but an aberration of 20/20 hindsight. Secondly, you might also notice that there were variations on Type List numbers that were probably made rather spontaneously. For example, consider the Type 60 with its many “K” variations to designate different body styles. Also consider how the Type 356 was initially a tube frame chassis then changed to a sheet metal chassis with the annotation 356/2 but the /2 later reused to describe different body/engine offerings. Then there were the variants on the 356 annotated as 356 SL, 356A, 356B, and 356C designations and in parallel there were the 356 T1 through 356 T7 designations. Not to mention, of course, the trademark infringement threat that caused the Type 901 to be externally re-designated as the 911. -

Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 2-10-2009 The Atlantic Mind: Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World Mark J. Fleszar Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Fleszar, Mark J., "The Atlantic Mind: Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ATLANTIC MIND: ZEPHANIAH KINGSLEY, SLAVERY, AND THE POLITICS OF RACE IN THE ATLANTIC WORLD by MARK J. FLESZAR Under the Direction of Dr. Jared Poley and Dr. H. Robert Baker ABSTRACT Enlightenment philosophers had long feared the effects of crisscrossing boundaries, both real and imagined. Such fears were based on what they considered a brutal ocean space frequented by protean shape-shifters with a dogma of ruthless exploitation and profit. This intellectual study outlines the formation and fragmentation of a fluctuating worldview as experienced through the circum-Atlantic life and travels of merchant, slaveowner, and slave trader Zephaniah Kingsley during the Era of Revolution. It argues that the process began from experiencing the costs of loyalty to the idea of the British Crown and was tempered by the pervasiveness of violence, mobility, anxiety, and adaptation found in the booming Atlantic markets of the Caribbean during the Haitian Revolution. -

BLACK JACKS Written by Eric Karkheck

BLACK JACKS Written By Eric Karkheck (323) 736-6718 [email protected] Black Jack: noun, 18th Century An African warrior who becomes a pirate. FADE IN: EXT. VILLAGE BEACH, WEST AFRICA - DAY Statuesque TERU FURRO (30s) sits in the sand braiding ropes together into a fishing net. She is left handed because her right is missing its pinky finger. She looks out to the vast ocean. EXT. HIDDEN LAGOON - DAY Blue sky and puffy clouds reflect in the surface of the water. A dugout canoe with a sail skims across it. Tall and muscular CHAGA FURRO (30s) paddles in the stern. His skinny son KUMI (13) is in the bow. Chaga spots a school of tilapia. CHAGA Kumi, mind the net. (Note: Italicized dialogue is spoken in Akan African and subtitled in English.) KUMI Yes, father. Kumi gathers the net into his arms. CHAGA Do it clean. If the lines tangle it will scatter the school. Kumi throws the net overboard. He pulls in the ropes. KUMI They are strong. The ropes zip through Kumi's hands. Chaga catches them. CHAGA Place your feet on the side to give you leverage. Together, they pull the net up and into the canoe to release a wave of fish onto themselves. CHAGA Ha Ha!! Do you see this my son?! Good, good, very good! Mother will be pleased. Yes. 2. Chaga wraps Kumi in a warm hug. Kumi halfheartedly returns the embrace. EXT. ATLANTIC OCEAN - DAY Chaga paddles toward land. Kumi scans the ocean horizon through a mariner's telescope. KUMI Can we go on a trip somewhere? Maybe to visit another tribe? CHAGA We are fishermen. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

White Lies: Human Property and Domestic Slavery Aboard the Slave Ship Creole

Atlantic Studies ISSN: 1478-8810 (Print) 1740-4649 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjas20 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson To cite this article: Walter Johnson (2008) White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole , Atlantic Studies, 5:2, 237-263, DOI: 10.1080/14788810802149733 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810802149733 Published online: 26 Sep 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 679 View related articles Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjas20 Download by: [Harvard Library] Date: 04 June 2017, At: 20:53 Atlantic Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, August 2008, 237Á263 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson* We cannot suppress the slave trade Á it is a natural operation, as old and constant as the ocean. George Fitzhugh It is one thing to manage a company of slaves on a Virginia plantation and quite another to quell an insurrection on the lonely billows of the Atlantic, where every breeze speaks of courage and liberty. Frederick Douglass This paper explores the voyage of the slave ship Creole, which left Virginia in 1841 with a cargo of 135 persons bound for New Orleans. Although the importation of slaves from Africa into the United States was banned from 1808, the expansion of slavery into the American Southwest took the form of forced migration within the United States, or at least beneath the United States’s flag. -

A Trip Through Autoland Saxony How Felix Discovered That the Future of the Automobile Starts Right Here at His Very Doorstep

AUTO! A Trip Through Autoland Saxony How Felix discovered that the future of the automobile starts right here at his very doorstep. Hey Oldster, ... FeFelix wwhhispers as a greeting. Then hhee cacasttss a critical ggllancece what’s up? inside tthhe DKW F1, built almost 90 years aaggo iinn Zwickauu,, Saxony. Evveery couple ofof wweeeks, Felix is draawwn from tthhe WWeesst Saxxoon UnUniveversity of AAppplied Sciencesces Zwickau to tthhe August Horch Museum – and hhee always lingers for tthhe lloongest time witthh “his” DKW oldtimer. Some of FeFelix’ fellow sttuudents ccllaim he’s having conversations wwiitthh tthehe vinttaage ccaar; so far, FeFelix hhaassnn’t deniieded iitt ... YESTERDAY IN “AUTOLAND SAXONY:” 1900 AUDI is born “Coswiga” – the first passenger car from Saxony, built in Coswig in . in Saxony – in 1910 founded by the auto pioneer August Horch (under the Latin version of ces in the 1932 his last name) in Zwickau. In , Horch, Audi, DKW, and Wanderer joined for Steering wheel on Chemnitz-based “Auto-Union.” It’s trademark – the four interlocked rings. – what most car drivers take for granted today began its the left, gearshift lever in the center 1921 mass-produced front-wheel- global success story in Saxony (Audi Factory) in . The 1931 Lightweight drive was launched for the first time ever in in the DKW F1 from Saxony. 1955 s- construction with thermosetting plastics – In , Germany’s first vehicle with a mas renaissance of produced plastic body was the Sachsenring P70 (later known as “Trabant”). The 1990 “Autoland Saxony” was launched by VW in – with the founding of the VW Sachsen . -

Volkswagen AG Annual Report 2009

Driving ideas. !..5!,2%0/24 Key Figures MFCBJN8><E>IFLG )''0 )''/ Mfcld\;XkX( M\_`Zc\jXc\jle`kj -#*'0#.+* -#).(#.)+ "'%- Gif[lZk`fele`kj -#',+#/)0 -#*+-#,(, Æ+%- <dgcfp\\jXk;\Z%*( *-/#,'' *-0#0)/ Æ'%+ )''0 )''/ =`eXeZ`Xc;XkX@=IJj #d`cc`fe JXc\ji\m\el\ (',#(/. ((*#/'/ Æ.%- Fg\iXk`e^gif]`k (#/,, -#*** Æ.'%. Gif]`kY\]fi\kXo (#)-( -#-'/ Æ/'%0 Gif]`kX]k\ikXo 0(( +#-// Æ/'%- Gif]`kXkki`YlkXYc\kfj_Xi\_fc[\ijf]MfcbjnX^\e8> 0-' +#.,* Æ.0%/ :Xj_]cfnj]ifdfg\iXk`e^XZk`m`k`\j)()#.+( )#.') o :Xj_]cfnj]ifd`em\jk`e^XZk`m`k`\j)('#+)/ ((#-(* Æ('%) 8lkfdfk`m\;`m`j`fe* <9@K;8+ /#'', ()#('/ Æ**%0 :Xj_]cfnj]ifdfg\iXk`e^XZk`m`k`\j) ()#/(, /#/'' "+,%- :Xj_]cfnj]ifd`em\jk`e^XZk`m`k`\j)#,('#),) ((#+.0 Æ('%. f]n_`Z_1`em\jkd\ekj`egifg\ikp#gcXekXe[\hl`gd\ek),#./* -#..* Æ(+%- XjXg\iZ\ekX^\f]jXc\ji\m\el\ -%) -%- ZXg`kXc`q\[[\m\cfgd\ekZfjkj (#0+/ )#)(- Æ()%( XjXg\iZ\ekX^\f]jXc\ji\m\el\ )%( )%) E\kZXj_]cfn )#,-* Æ)#-.0 o E\kc`hl`[`kpXk;\Z%*( ('#-*- /#'*0 "*)%* )''0 )''/ I\klieiXk`fj`e I\kliefejXc\jY\]fi\kXo (%) ,%/ I\kliefe`em\jkd\ekX]k\ikXo8lkfdfk`m\;`m`j`fe *%/ ('%0 I\kliefe\hl`kpY\]fi\kXo=`eXeZ`XcJ\im`Z\j;`m`j`fe -.%0 ()%( ( @eZcl[`e^mfcld\[XkX]fik_\m\_`Zc\$gif[lZk`fe`em\jkd\ekjJ_Xe^_X`$MfcbjnX^\e8lkfdfk`m\:fdgXepCk[% Xe[=8N$MfcbjnX^\e8lkfdfk`m\:fdgXepCk[%#n_`Z_Xi\XZZflek\[]filj`e^k_\\hl`kpd\k_f[% ) )''/X[aljk\[% * @eZcl[`e^XccfZXk`fef]Zfejfc`[Xk`feX[aljkd\ekjY\kn\\ek_\8lkfdfk`m\Xe[=`eXeZ`XcJ\im`Z\j[`m`j`fej% + Fg\iXk`e^gif]`kgclje\k[\gi\Z`Xk`fe&Xdfik`qXk`feXe[`dgX`id\ekcfjj\j&i\m\ijXcjf]`dgX`id\ekcfjj\jfegifg\ikp#gcXekXe[\hl`gd\ek# ZXg`kXc`q\[[\m\cfgd\ekZfjkj#c\Xj`e^Xe[i\ekXcXjj\kj#^ff[n`ccXe[]`eXeZ`XcXjj\kjXji\gfik\[`ek_\ZXj_]cfnjkXk\d\ek% , <oZcl[`e^XZhl`j`k`feXe[[`jgfjXcf]\hl`kp`em\jkd\ekj1Ñ.#,/,d`cc`feÑ/#/.0d`cc`fe % - Gif]`kY\]fi\kXoXjXg\iZ\ekX^\f]Xm\iX^\\hl`kp% . -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Vorlage Für Geschäftsbrief

AUDI AG 85045 Ingolstadt Germany History of the Four Rings AUDI AG can look back on a very eventful and varied history; its tradition of car and motorcycle manufacturing goes right back to the 19th century. The Audi and Horch brands in the town of Zwickau in Saxony, Wanderer in Chemnitz and DKW in Zschopau all enriched Germany’s automobile industry and contributed to the development of the motor vehicle. These four brands came together in 1932 to form Auto Union AG, the second largest motor-vehicle manufacturer in Germany in terms of total production volume. The new company chose as its emblem four interlinked rings, which even today remind us of the four founder companies. After the Second World War the Soviet occupying power requisitioned and dismantled Auto Union AG’s production facilities in Saxony. Leading company executives made their way to Bavaria, and in 1949 established a new company, Auto Union GmbH, which continued the tradition associated with the four-ring emblem. In 1969, Auto Union GmbH and NSU merged to form Audi NSU Auto Union AG, which since 1985 has been known as AUDI AG and has its head offices in Ingolstadt. The Four Rings remain the company’s identifying symbol. Horch This company’s activities are closely associated with its original founder August Horch, one of Germany’s automobile manufacturing pioneers. After graduating from the Technical Academy in Mittweida, Saxony he worked on engine construction and later as head of the motor vehicle production department of the Carl Benz company in Mannheim. In 1899 he started his own business, Horch & Cie., in Cologne. -

1Ba704, a NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE in the MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN and MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION, THE PEOPLE OF AFRICATOWN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY AND THE SLAVE WRECKS PROJECT PREPARED BY SEARCH INC. MAY 2019 ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION 468 SOUTH PERRY STREET PO BOX 300900 MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36130 PREPARED BY ______________________________ JAMES P. DELGADO, PHD, RPA SEARCH PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY DEBORAH E. MARX, MA, RPA KYLE LENT, MA, RPA JOSEPH GRINNAN, MA, RPA ALEXANDER J. DECARO, MA, RPA SEARCH INC. WWW.SEARCHINC.COM MAY 2019 SEARCH May 2019 Archaeological Investigations of 1Ba704, A Nineteenth-Century Shipwreck Site in the Mobile River Final Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Between December 12 and 15, 2018, and on January 28, 2019, a SEARCH Inc. (SEARCH) team of archaeologists composed of Joseph Grinnan, MA, Kyle Lent, MA, Deborah Marx, MA, Alexander DeCaro, MA, and Raymond Tubby, MA, and directed by James P. Delgado, PhD, examined and documented 1Ba704, a submerged cultural resource in a section of the Mobile River, in Baldwin County, Alabama. The team conducted current investigation at the request of and under the supervision of Alabama Historical Commission (AHC); Alabama State Archaeologist, Stacye Hathorn of AHC monitored the project. This work builds upon two earlier field projects. The first, in March 2018, assessed the Twelvemile Wreck Site (1Ba694), and the second, in July 2018, was a comprehensive remote-sensing survey and subsequent diver investigations of the east channel of a portion the Mobile River (Delgado et al. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS David M. Williams and Andrew P. White as well as those from the humanities. The (comp.). A Select Bibliography of British and section on Maritime Law lists work on Irish University Theses About Maritime pollution and the maritime environment, and History, 1792-1990. St. John's, Newfound• on the exploitation of sea resources. It is land: International Maritime Economic particularly useful to have the Open Univer• History Association, 1992. 179 pp., geo• sity and the C.NAA. theses listed. graphical and nominal indices. £10 or $20, The subjects are arranged under twenty- paper; ISBN 0-969588-5. five broad headings; there are numerous chronological geographic and subject sub• The establishment of the International and divisions and an author and geographic British Commissions for Maritime History, index to facilitate cross referencing. Though both of which have assisted in the publica• it is mildly irritating to have details some• tion of this bibliography, illustrates the times split between one column and the steadily growing interest in maritime history next, the whole book is generally convenient during the last thirty years. However, the and easy to use. The introduction explains increasing volume of research in this field the reasons for the format of the biblio• and the varied, detailed work of postgradu• graphy, its pattern of classification and the ate theses have often proved difficult to location and availability of theses. This has locate and equally difficult to consult. This recently much improved and an ASLIB bibliography provides access to this "enor• number is helpfully listed for the majority of mously rich resource" (p.