Haere Whakamua, Hoki Whakamuri, Going Forward, Thinking Back : Tribal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Far North Districts Rugby League Kerikeri, Moerewa, Kaikohe, Whanau, Otaua, Waima, Pawarenga, Muriwhenua, Tehiku, Ngati Kahu, the Academy

Far North Districts Rugby League Kerikeri, Moerewa, Kaikohe, Whanau, Otaua, Waima, Pawarenga, Muriwhenua, Tehiku, Ngati Kahu, The Academy PO Box 546 Kaitaia 60 North Rd Kaitaia 09 408 1800 Monday 23 November 2015 To the Member Clubs of the Far North District Rugby League Rugby League Northland’s (RLN) rejection of our proposals in favour of a structure that has always favoured Whangarei clubs over the clubs of the Far North is disappointing, but not surprising given that the Board is essentially made up of people who live in and around Whangarei. The cost of travel means there has never been a level playing field for Rugby League in Northland. The 6 Whangarei clubs travel no more than 30 minutes for 70% of their games; the far north clubs travel up to 5 hours for 70% of theirs. RLN has done nothing to remedy the situation. Even when we offered solutions, RLN rejected them. They: Rejected our proposal for a two-division competition that would make it easier for Far North clubs to participate in Rugby League. Rejected our proposal to have the Top 8 clubs in both Whangarei and the Far North play off in a high-profile high-quality Finals Series. Rejected our proposal for a north-south competition that would help build district rivalry, provide a trial series for the Northland Swords, and help promote the game. Refused to set up a group of 3 from the Far North, 3 from Whangarei and a representative of the Board to see how our proposal might actually work. Refuses to recognise that we have 5 new clubs wanting to join our 5 existing clubs, because they are excited about playing in a 10-team Far North competition. -

Oakura July 2003

he akura essenger This month JULY 2003 Coastal Schools’ Education Development Group Pictures on page 13 The Minister of Education, Trevor Mallard, has signalled a review of schooling, to include Pungarehu, Warea, Newell, Okato Primary, Okato College, Oakura and Omata schools. The reference group of representatives from the area has been selected to oversee the process and represent the community’s perspective. Each school has 2 representatives and a Principal rep from the Primary and Secondary sector. Other representatives include, iwi, early childhood education, NZEI, PPTA, local politicians, Federated Farmers, School’s Trustee Association and the Ministry of Education in the form of a project manager. In general the objectives of the reference group are to be a forum for discussion of is- sues with the project manager. There will be plenty of opportunity for the local com- Card from the Queen for munities to have input. Sam and Tess Dobbin Page 22 The timeframe is to have an initial suggestion from the Project Manager by September 2003. Consultation will follow until December with a preliminary announcement from the Ministry of Education in January 2004. Further consultation will follow with the Minister’s final announcement likely in June 2004. This will allow for any develop- ment needed to be carried out by the start of the 2005 school year. The positive outcome from a review is that we continue to offer quality education for Which way is up? the children of our communities for the next 10 to 15 years as the demographics of our communities are changing. Nick Barrett, Omata B.O.T Chairperson Page 5 Our very own Pukekura Local artist “Pacifica of Land on Sea” Park? Page 11 exhibits in Florence Local artist Caz Novak has been invited to exhibit at the Interna- tional Biennale of Contemporary Art in Florence this year. -

![In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry I Te Kōti Matua O Aotearoa Tāmaki Makaurau Rohe Civ-2019-404-2672 [2020] Nz](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6165/in-the-high-court-of-new-zealand-auckland-registry-i-te-k%C5%8Dti-matua-o-aotearoa-t%C4%81maki-makaurau-rohe-civ-2019-404-2672-2020-nz-46165.webp)

In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry I Te Kōti Matua O Aotearoa Tāmaki Makaurau Rohe Civ-2019-404-2672 [2020] Nz

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND AUCKLAND REGISTRY I TE KŌTI MATUA O AOTEAROA TĀMAKI MAKAURAU ROHE CIV-2019-404-2672 [2020] NZHC 2768 UNDER Resource Management Act 1991. IN THE MATTER of an appeal under section 299 of the Resource Management Act 1991 against a decision of the Environment Court. BETWEEN NGĀTI MARU TRUST Appellant AND NGĀTI WHĀTUA ŌRĀKEI WHAIA MAIA LIMITED Respondent (Continued next page) Hearing: 18 June 2020 Auckland Council submissions received 26 June 2020 Respondent submissions received 1 July 2020 Appellants’ submissions received 26 June and 6 July 2020 Counsel: A Warren and K Ketu for Appellants L Fraser and N M de Wit for Respondent R S Abraham for Panuku Development Auckland S F Quinn for Auckland Council Judgment: 21 October 2020 JUDGMENT OF WHATA J This judgment was delivered by me on 21 October 2020 at 4.00 pm, pursuant to Rule 11.5 of the High Court Rules. Registrar/Deputy Registrar Date: …………………………. Solicitors: McCaw Lewis, Hamilton Simpson Grierson, Auckland DLA Piper, Auckland Chapman Tripp, Auckland NGĀTI MARU TRUST v NGĀTI WHĀTUA ŌRĀKEI WHAIA MAIA LIMITED [2020] NZHC 2768 [21 October 2020] CIV-2019-404-2673 BETWEEN TE ĀKITA O WAIOHUA WAKA TAUA INCORPORATED SOCIETY Appellant AND NGĀTI WHĀTUA NGĀTI WHĀTUA ŌRĀKEI WHAIA MAIA LIMITED Respondent CIV-2019-404-2676 BETWEEN TE PATUKIRIKIRI TRUST Appellant AND NGĀTI WHĀTUA NGĀTI WHĀTUA ŌRĀKEI WHAIA MAIA LIMITED Respondent [1] The Environment Court was asked to answer the following question (the Agreed Question): Does the Environment Court have jurisdiction to determine whether any tribe holds primary mana whenua over an area the subject of a resource consent application: (a) generally; or (b) where relevant to claimed cultural effects of the application and the wording of resource consent conditions. -

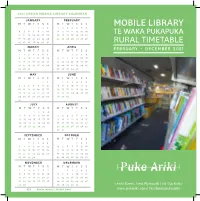

Mobile Library

2021 URBAN MOBILE LIBRARY CALENDAR JANUARY FEBRUARY M T W T F S S M T W T F S S MOBILE LIBRARY 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 TE WAKA PUKAPUKA 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 RURAL TIMETABLE MARCH APRIL M T W T F S S M T W T F S S FEBRUARY - DECEMBER 2021 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 MAY JUNE M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 31 JULY AUGUST M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 1 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 SEPTEMBER OCTOBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 NOVEMBER DECEMBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 1 Ariki Street, New Plymouth | 06-759 6060 KEY RURAL MOBILE LIBRARY DAYS www.pukariki.com | facebook/pukeariki Tuesday Feb 9, 23 Mar 9, 23 April 6 May 4, 18 TE WAKA PUKAPUKA June 1, 15, 29 July 27 Aug 10, 24 Sept 7, 21 Oct 19 Nov 2, 16, 30 Dec 14 Waitoriki School 9:30am – 10:15am Norfolk School 10:30am – 11:30am FEBRUARY - DECEMBER 2021 Ratapiko School 11:45am – 12:30pm Kaimata School 1:30pm – 2:30pm The Mobile Library/Te Waka Pukapuka stops at a street near you every second week. -

Ngāti Hāmua Environmental Education Sheets

NGTI HMUA ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION SHEETS Produced by Rangitne o Wairarapa Inc in conjunction with Greater Wellington 2006 2 NGTI HMUA ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION SHEETS This education resource provides the reader with information about the environment from the perspective of the Ngti Hmua hap of Rangitne o Wairarapa iwi. There are 9 separate sheets with each one focussing on a different aspect of Mori customary belief. The first two sheets look at history relating to Ngti Hmua starting with the creation myth and the Maori gods (Nga Atua). The second sheet (Tupuna) looks at the Ngti Hmua ancestors that have some link to the Wairarapa including Maui – who fished up Aotearoa, Kupe – the first explorer to these shores, Whtonga aboard the Kurahaup waka and his descendants. The remaining sheets describe the values, practices or uses that Ngti Hmua applied to their environment in the Wairarapa valleys, plains, mountains, waterways and coastal areas. The recording of this information was undertaken so that people from all backgrounds can gain an appreciation of the awareness that the kaumtua of Ngti Hmua have of the natural world. Rangitne o Wairarapa and Greater Wellington Regional Council are pleased to present this information to the people of the Wairarapa and beyond. This resource was created as part of the regional council’s iwi project funding which helps iwi to engage in environmental matters. For further information please contact Rangitne o Wairarapa Runanga 06 370 0600 or Greater Wellington 06 378 2484 Na reira Nga mihi nui ki a koutou katoa 3 CONTENTS Page SHEET 1 Nga Atua –The Gods 4 2 Nga Tupuna – The Ancestors 8 3 Te Whenua – The Land 14 4 Nga Maunga – The Mountains 17 5 Te Moana – The Ocean 19 6 Nga Mokopuna o Tnemahuta – Flora 22 7 Nga Mokopuna o Tnemahuta – Fauna 29 8 Wai Tapu – Waterways 33 9 Kawa – Protocols 35 4 Ngti Hmua Environmental Education series - SHEET 1 of 9 NGA ATUA - THE GODS Introduction The Cosmic Genealogy The part that the gods play in the life of all M ori is hugely s ignificant. -

NGĀTI REHUA-NGĀTIWAI KI AOTEA TRUST BOARD TRUSTEE's HUI #8, 5 Pm Monday 20 May 2019 Zoom Hui 1. KARAKIA Hui Opened by Way O

NGĀTI REHUA-NGĀTIWAI KI AOTEA TRUST BOARD TRUSTEE’S HUI #8, 5 pm Monday 20 May 2019 Zoom Hui 1. KARAKIA Hui opened by way of karakia from Tavake. 2. APOLOGIES Apologies from Hillarey. 3. TRUSTEES IN ATTENDANCE Aperahama Edwards, Valmaine Toki, Bruce Davis, Tavake Afeaki. 4. LAST MEETINGS MINUTES – Sat 4 May 2019 Draft Board Hui #6 Minutes circulated for consideration This item was deferred for consideration at the next Board Hui because although BD, VT and TA had attended that hui, but BD had not had a chance to look at the draft minutes. 5. MATTERS ARISING Storage King Received NRNWTB financial statements for the last three years. ElectioNZ Beneficiary Database Tavake received this excel spreadsheet database from ElectioNZ and had forwarded it to the other trustees with a mihi whakatapu and a request that we all respect the privacy of the peoples’ details and the confidentiality of the information it contained. Received an email from Hillarey to all trustees on the 16th of May alleging there has been a breach of confidentiality by the Chair for circulating the database electronically. Tavake had emailed in reply to ask Hillarey for more details about her comment but BD advised that she was overseas. Bruce attended a hui with Ngāti Manuhiri involving some people into their trust. He said that one of the Trustees on the Ngāti Manuhiri confronted Mook Hohneck with some comments about whakapapa? BD said the only way they would have got the whakapapa, was by someone having provided them with what Tavake had circulated electronically to the Trustees. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

And Did She Cry in Māori?”

“ ... AND DID SHE CRY IN MĀORI?” RECOVERING, REASSEMBLING AND RESTORYING TAINUI ANCESTRESSES IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Diane Gordon-Burns Tainui Waka—Waikato Iwi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Canterbury 2014 Preface Waikato taniwha rau, he piko he taniwha he piko he taniwha Waikato River, the ancestral river of Waikato iwi, imbued with its own mauri and life force through its sheer length and breadth, signifies the strength and power of Tainui people. The above proverb establishes the rights and authority of Tainui iwi to its history and future. Translated as “Waikato of a hundred chiefs, at every bend a chief, at every bend a chief”, it tells of the magnitude of the significant peoples on every bend of its great banks.1 Many of those peoples include Tainui women whose stories of leadership, strength, status and connection with the Waikato River have been diminished or written out of the histories that we currently hold of Tainui. Instead, Tainui men have often been valorised and their roles inflated at the expense of Tainui women, who have been politically, socially, sexually, and economically downplayed. In this study therefore I honour the traditional oral knowledges of a small selection of our tīpuna whaea. I make connections with Tainui born women and those women who married into Tainui. The recognition of traditional oral knowledges is important because without those histories, remembrances and reconnections of our pasts, the strengths and identities which are Tainui women will be lost. Stereotypical male narrative has enforced a female passivity where women’s strengths and importance have become lesser known. -

MA10: Museums – Who Needs Them? Articulating Our Relevance and Value in Changing and Challenging Times

MA10: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? Articulating our relevance and value in changing and challenging times HOST ORGANISATIONS MAJOR SPONSORS MA10: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? Articulating our relevance and value in changing and challenging times WEDNESDAY 14 – FRIDAY 16 APRIL, 2010 HOSTED BY PUKE ARIKI AND GOVETt-BREWSTER ART GALLERY VENUE: TSB SHOWPLACE, NEW PLYMOUTH THEME: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? MA10 will focus on four broad themes that will be addressed by leading international and national keynote speakers, workshops and case studies: Social impact and creative capital: what is the social relevance and contribution of museums and galleries within a broader framework? Community engagement: how do we undertake audience development, motivate stakeholders as advocates, and activate funders? Economic impact and cultural tourism: how do we demonstrate our economic value and contribution, and how do we develop economic collaborations? Current climate: how do we meet these challenges in the current economic climate, the changing political landscape nationally and locally, and mediate changing public and visitor expectations? INTERNATIONAL SPEAKERS INCLUDE MUSEUMS AOTEAROA Tony Ellwood Director, Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art Museums Aotearoa is New Zealand’s Elaine Heumann Gurian Museum Advisor and Consultant independent professional peak body for museums and those who work Michael Houlihan Director General, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales in or have an interest in museums. Chief Executive designate, Te Papa Members include museums, public art galleries, historical societies, Michael Huxley Manager of Finance, Museums & Galleries NSW science centres, people who work within these institutions and NATIONAL SPEAKERS INCLUDE individuals connected or associated Barbara McKerrow Chief Executive Officer, New Plymouth District Council with arts, culture and heritage in New Zealand. -

Indigenous Bodies: Ordinary Lives

CHAPTER 8 Indigenous Bodies: Ordinary Lives Brendan Hokowhitu Ōpōtiki Red with cold Māori boy feet speckled with blades of colonial green Glued with dew West water wept down from Raukūmara mountains Wafed up east from the Pacifc Anxiety, ambiguity, madness1 mbivalence is the overwhelming feeling that haunts my relationship with physicality. Not only my body, but the bodies of an imagined multitude of AIndigenous peoples dissected and made whole again via the violent synthesis of the colonial project. Like my own ambivalence (and by “ambivalence” I refer to simultaneous abhorrence and desire), the relationship between Indigenous peoples and physicality faces the anxiety of representation felt within Indigenous studies in general. Tis introduction to the possibilities of a critical pedagogy is one of biopolitical transformation, from the innocence of jumping for joy, to the moment I become aware of my body, the moment of self-consciousness in the archive, in knowing Indigenous bodies written upon and etched by colonization, and out the other side towards radical Indigenous scholarship. Tis is, however, not a narrative of modernity, of transformation, of transcendence of the mind through the body. I didn’t know it then, but this transformation was a genealogical method un- folding through the production of corporeality: part whakapapa (genealogy), part comprehension of the biopolitics that placate and make rebellious the Indigenous 164 Indigenous Bodies: Ordinary Lives body. Plato’s cave, Descartes’ blueprint, racism, imperial discourse, colonization, liberation, the naturalness of “physicality” and “indigeneity.” Tis madness only makes sense via the centrality of Indigenous physicality. Physicality is that terminal hub, the dense transfer point where competing, contrasting, synthesizing, and dissident concepts hover to make possible the various ways that the Indigenous body materializes through and because of colonization. -

Report on the Crown's Foreshore and Seabed Policy

Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz REPORT ON THE CROWN’S FORESHORE AND SEABED POLICY Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz REPORT ON THECROWN’S FORESHORE AND SEABEDPOLICY WAI 107 1 WAITANGI TRIBUNAL REPORT 2004 Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz The cover design by Cliff Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfolds in a pattern not yet completely known A Waitangi Tribunal report isbn 1-86956-272-0 www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Typeset by the Waitangi Tribunal Published 2004 by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by SecuraCopy, Wellington, New Zealand Set in Adobe Minion and Cronos multiple master typefaces The diagram on page 119 was taken from Gerard Willis, Jane Gunn, and David Hill, ‘Oceans Policy Stocktake: Part 1 – Legislation and Policy Review’, report prepared for the Oceans Policy Secretariat, 2002, and is reproduced here by permission of the Ministry for the Environment. It was originally adapted from one in Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Setting Course for a Sustainable Future: The Management of New Zealand’s Marine Environment (Wellington: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, 1999). Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Downloaded from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz CONTENTS Letter of transmittal . ix Introduction . xi Chapter 1: Tikanga . 1 1.1 What is ‘tikanga’? . 1 1.2 Tikanga in the context of this inquiry . -

The Whare-Oohia: Traditional Maori Education for a Contemporary World

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WHARE-OOHIA: TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY WORLD A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Education at Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand Na Taiarahia Melbourne 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS He Mihi CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 The Research Question…………………………………….. 5 1.2 The Thesis Structure……………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER 2: HISTORY OF TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 9 2.1 The Origins of Traditional Maaori Education…………….. 9 2.2 The Whare as an Educational Institute……………………. 10 2.3 Education as a Purposeful Engagement…………………… 13 2.4 Whakapapa (Genealogy) in Education…………………….. 14 CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW 16 3.1 Western Authors: Percy Smith;...……………………………………………… 16 Elsdon Best;..……………………………………………… 22 Bronwyn Elsmore; ……………………………………….. 24 3.2 Maaori Authors: Pei Te Hurinui Jones;..…………………………………….. 25 Samuel Robinson…………………………………………... 30 CHAPTER 4: RESEARCHING TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 33 4.1 Cultural Safety…………………………………………….. 33 4.2 Maaori Research Frameworks…………………………….. 35 4.3 The Research Process……………………………………… 38 CHAPTER 5: KURA - AN ANCIENT SCHOOL OF MAAORI EDUCATION 42 5.1 The Education of Te Kura-i-awaawa;……………………… 43 Whatumanawa - Of Enlightenment..……………………… 46 5.2 Rangi, Papa and their Children, the Atua:…………………. 48 Nga Atua Taane - The Male Atua…………………………. 49 Nga Atua Waahine - The Female Atua…………………….. 52 5.3 Pedagogy of Te Kura-i-awaawa…………………………… 53 CHAPTER 6: TE WHARE-WAANANGA - OF PHILOSOPHICAL EDUCATION 55 6.1 Whare-maire of Tuhoe, and Tupapakurau: Tupapakurau;...…………………………………………….