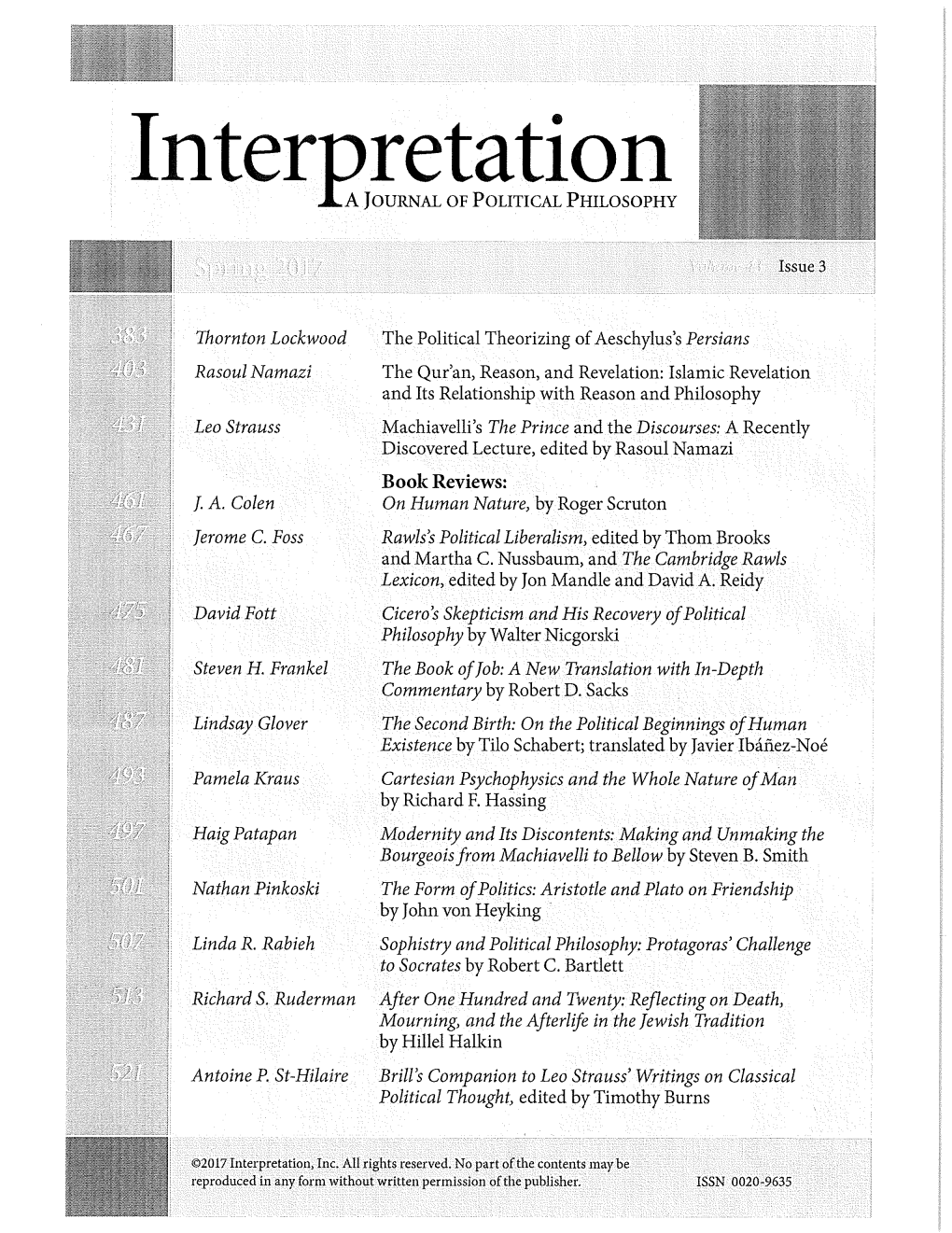

Interpretation -La Journal of Political Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; Proquest Pg

The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1972; 13, 4; ProQuest pg. 387 The Conditions of Dramatic Production to the Death of Aeschylus N. G. L. Hammond TUDENTS of ancient history sometimes fall into the error of read Sing their history backwards. They assume that the features of a fully developed institution were already there in its earliest form. Something similar seems to have happened recently in the study of the early Attic theatre. Thus T. B. L. Webster introduces his excellent list of monuments illustrating tragedy and satyr-play with the following sentences: "Nothing, except the remains of the old Dionysos temple, helps us to envisage the earliest tragic background. The references to the plays of Aeschylus are to the lines of the Loeb edition. I am most grateful to G. S. Kirk, H. D. F. Kitto, D. W. Lucas, F. H. Sandbach, B. A. Sparkes and Homer Thompson for their criticisms, which have contributed greatly to the final form of this article. The students of the Classical Society at Bristol produce a Greek play each year, and on one occasion they combined with the boys of Bristol Grammar School and the Cathedral School to produce Aeschylus' Oresteia; they have made me think about the problems of staging. The following abbreviations are used: AAG: The Athenian Agora, a Guide to the Excavation and Museum! (Athens 1962). ARNon, Conventions: P. D. Arnott, Greek Scenic Conventions in the Fifth Century B.C. (Oxford 1962). BIEBER, History: M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre2 (Princeton 1961). -

Herodotus, Xerxes and the Persian Wars IAN PLANT, DEPARTMENT of ANCIENT HISTORY

Herodotus, Xerxes and the Persian Wars IAN PLANT, DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT HISTORY Xerxes: Xerxes’ tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam Herodotus: 2nd century AD: found in Egypt. A Roman copy of a Greek original from the first half of the 4th century BC. Met. Museum New York 91.8 History looking at the evidence • Our understanding of the past filtered through our present • What happened? • Why did it happen? • How can we know? • Key focus is on information • Critical collection of information (what is relevant?) • Critical evaluation of information (what is reliable?) • Critical questioning of information (what questions need to be asked?) • These are essential transferable skills in the Information Age • Let’s look at some examples from Herodotus’ history of the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC • Is the evidence from: ― Primary sources: original sources; close to origin of information. ― Secondary sources: sources which cite, comment on or build upon primary sources. ― Tertiary source: cites only secondary sources; does not look at primary sources. • Is it the evidence : ― Reliable; relevant ― Have I analysed it critically? Herodotus: the problem… Succession of Xerxes 7.3 While Darius delayed making his decision [about his successor], it chanced that at this time Demaratus son of Ariston had come up to Susa, in voluntary exile from Lacedaemonia after he had lost the kingship of Sparta. [2] Learning of the contention between the sons of Darius, this man, as the story goes, came and advised Xerxes to add this to what he said: that he had been born when Darius was already king and ruler of Persia, but Artobazanes when Darius was yet a subject; [3] therefore it was neither reasonable nor just that anyone should have the royal privilege before him. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

The Chorus of Aeschylus' Choephori

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title The Chorus of Aeschylus' Choephori Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8zv1j39h Author McCall, Marsh Publication Date 1990-04-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE CHORUS OF AESCHYLUS’ CHOEPHORI* Marsh McCall Stanford University I wish to ask two questions about the chorus of Choephori. First, who exactly are they? Second, what dramatic personality and functions does Aeschylus give to them, and are these congruent with what we might, or do, expect? Even with the appearance of Garvie’s fine and thorough commentary on Choephori,1 there is nothing approaching consensus on either of these questions. I think it possible to settle the first and more concrete one and to advance understanding of the second, though in an unsettling way. At the end of the paper, I shall offer an opinion on how the particular investigation of the Choephori chorus may relate to the further and even more basic question: in what sense, if at all, is there a unified choral voice throughout the Oresteia or throughout Aeschylus? * * * * * First, then, identity. The chorus of Choephori consist either of unspecified foreign slave women or of specifically Trojan slave women, but which? Commentators and critics are split. As a sample, Verrall, Tucker, Wilamowitz, Lattimore are for unspecified generic foreign slave women; Conington, Sidgwick, Rose, Lloyd-Jones for specifically Trojan slave women.2 And many scholars, no matter how detailed their discussion of the play and its chorus—Lebeck, Taplin, and Garvie3 may serve as examples—, make no real attempt at a firm identification at all. -

Late Sophocles: the Hero's Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Late Sophocles Late Sophocles The Hero’s Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus Thomas Van Nortwick University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © Thomas Van Nortwick 2015 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Van Nortwick, Thomas, 1946– . Late Sophocles : the hero’s evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus / Thomas Van Nortwick. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11956- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 472- 12108- 3 (ebook) 1. Sophocles— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Sophocles. Electra. 3. Sophocles. Oedipus at Colonus. 4. Sophocles. Philoctetes. I. Title. PA4417.V36 2015 882'.01— dc23 2014049364 For Nathan Greenberg colleague, mentor, and friend Preface Oh children, follow me. I am your new leader, as once you were for me. (Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 1542– 431) Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus ends with his most famous character walking serenely through the central doors of the stage building (skēnē) in the Theater of Dionysus and into the grove of the Eumenides. -

Sophocles' Electra

Sophocles’ Electra Dramatic action and important elements in the play, scene-by-scene Setting: Mycenae/Argos Background: 15-20 years ago, Agamemnon (here named as grandson of Pelops) was killed by his wife and lover Aegisthus (also grandson of Pelops). As a boy, Orestes, was evacuated by his sister Electra and the ‘Old Slave’ to Phocis, to the kingdom of Strophius (Agamemnon’s guest-friend and father of Pylades). Electra stayed in Mycenae, preserving her father’s memory and harbouring extreme hatred for her mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. She has a sister, Chrysothemis, who says that she accepts the situation. Prologue: 1- 85 (pp. 169-75) - Dawn at the palace of Atreus. Orestes, Pylades and the Old Slave arrive. Topography of wealthy Argos/Mycenae, and the bloody house of the Atreids. - The story of Orestes’ evacuation. ‘It is time to act!’ v. 22 - Apollo’s oracle at Delphi: Agamemnon was killed by deception; use deception (doloisi – cunning at p. 171 is a bit weak) to kill the murderers. - Orestes’ idea to send the Old Slave to the palace. Orestes and Pylades will arrive later with the urn containing the ‘ashes’ of Orestes. «Yes, often in the past I have known clever men dead in fiction but not dead; and then when they return home the honour they receive is all the greater» v. 62-4, p. 173 Orestes like Odysseus: return to house and riches - Electra is heard wailing. Old slave: “No time to lose”. Prologue: 86-120 (pp. 175-7) - Enter Electra, who addresses the light of day. -

Ionian Revolt to Marathon

2/26/2012 Lecture 11: Ionian Revolt to Marathon HIST 332 Spring 2012 Life for Greek poleis under Cyrus • Cyrus sent messages to the Ionians asking them to revolt against Lydian rule – Ionians refused After conquest: • Ionian cities offered to be Persian subjects under the same terms – Cyrus refused, citing the Ionians’ unwillingness to help – Median general Harpagus sent to conquer Ionia – Installed tyrants to rule for Persia Ionian Revolt (499-494 BCE) 499 Aristagoras, tyrant of Miletos wants to attack Naxos • He can’t pay for it – so persuades satrap to invade – The invasion fails • Aristogoras needs to repay Persians • leads rebellion against Persian tyrants • He goes to Greece to ask for help – Sparta refuses – Athens sends a fleet 1 2/26/2012 Cleomenes’ reply to Aristagoras • Aristagoras goes to Sparta to solicit help – tells King Cleomenes that the “Great King” lived three months from the sea (i.e. easy task) “Get out of Sparta before sundown, Milesian stranger, for you have no speech eloquent enough to induce the Lacedemonians to march for three months inland from the sea.” -Herodotus, Histories 5.50 Ionian Rebellion Against Persia Ionian cities rebel 498 Greeks from Ionia attempt to take Satrap capital of Sardis – fire breaks out • Temple of Ahura-Mazda is burned • Battle of Ephesus – Greeks routed 497-5 Persian Counter-Attack – Cyprus taken – Hellespont pacified 494 Sack of Miletus Satrap installs democracies in place of tyrannies Darius not pleased with the Greeks • Motives obscure – punishment of Athenian aid to Ionians – was -

Introduction to Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes

Introduction to Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes Ἕπτ’ ἐπὶ Θήβας [Hept' epi Thēbas “Seven Against Thebes”] from its first performance at the City Dionysia in 367 BCE, the third tragedy in Aeschylus’ first-prize winning tetralogy Laios- Oidipous-Seven Against Thebes-Sphinx,1 has been widely recognized as an exceptional tragedy. Some sixty-two years later its fame was confirmed by Aristophanes in his wonderful comedy on the subject of tragedy, Frogs. Aristophanes has Aeschylus say for himself that everyone who saw Seven Against Thebes fell in love with the idea of a heroic warrior. Aristophanes’ character Dionysus, the god in whose honor Attic dramas were especially written and produced on the stage and for whom the principal Athenian theater, on the south slope of the Acropolis was named, calls out Aeschylus for doing a disservice to Athens, making the Thebans to be so brave in battle—a left-handed compliment to the tragic poet—Aristophanes’ comic character Aeschylus deflects by saying, in effect, the Athenians could have exercised those qualities, but didn’t. He goes on to add that his Persians (which really couldn’t have been a corrective measure since it was produced in 472, five years earlier) inspired Athenians. In fact, as Aristophanes in seriousness might admit, a strong point of Aeschylus’ dramatic poetry, like Homer’s epics, is that allies and enemies are portrayed as lifelike or equally larger than life, evenhandedly critical, not patently reductive of a whole cast of characters on the other side. Aeschylus himself reportedly admitted -

Kommos in Sophocles’ Philoctetes (1081-1217) 277 15

Συναγωνίζεσθαι Studies in Honour of Guido Avezzù Edited by Silvia Bigliazzi, Francesco Lupi, Gherardo Ugolini Σ Skenè Studies I • 1 S K E N È Theatre and Drama Studies Executive Editor Guido Avezzù. General Editors Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Francesco Lupi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Susan Payne, Gherardo Ugolini. Managing Editors Serena Marchesi, Savina Stevanato. Editorial Staff Francesco Dall’Olio, Marco Duranti, Carina Fernandes, Antonietta Provenza, Emanuel Stelzer. Layout Editor Alex Zanutto. Advisory Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, Jean-Christophe Cavallin, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, Marco De Marinis, Tobias Döring, Pavel Drabek, Paul Edmondson, Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, Daniela Guardamagna, Stephen Halliwell, Robert Henke, Pierre Judet de la Combe, Eric Nicholson, Guido Paduano, Franco Perrelli, Didier Plassard, Donna Shalev, Susanne Wofford. Copyright © 2018 S K E N È All rights reserved. ISSN 2464-9295 ISBN 978-88-6464-503-2 Published in December 2018 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher Dir. Resp. (aut. Trib. di Verona): Guido Avezzù P.O. Box 149 c/o Mail Boxes Etc. (MBE 150) – Viale Col. Galliano, 51, 37138, Verona (I) S K E N È Theatre and Drama Studies http://www.skenejournal.it [email protected] Contents Silvia Bigliazzi - Francesco Lupi - Gherardo Ugolini Πρόλογος / Prologue 9 Part 1 – Τραγῳδία / Tragedy 1. Stephen Halliwell “We were there too”: Philosophers in the Theatre 15 2. Maria Grazia Bonanno Tutto il mondo (greco) è teatro. Appunti sulla messa-in-scena greca non solo drammatica 41 3. -

The Athenian Empire

Week 8: The Athenian Empire Lecture 13, The Delian League, Key Words Aeschylus’ Persians Plataea Mycale Second Ionian Revolt Samos Chios Lesbos Leotychidas Xanthippus Sestos Panhellenism Medizers Corinth Common Oaths Common Freedom Asia Minor Themistocles Pausanias Dorcis Hegemony by Invitation Aristides Uliades of Samos Byzantium Hybris Delos Ionia Hellespont Caria Thrace NATO UN Phoros Hellenotamias Synod Local Autonomy 1 Lecture 14, From League to Empire, Key Words Eion Strymon Scyros Dolopians Cleruchy Carystus Naxos Eurymedon Caria Lycia Thasos Ennea Hodoi Indemnity Diodorus Thucydides Athenian Imperial Democracy Tribute Lists Garrisons 2 Chronological Table for the Pentekontaetia 479-431 481/0 Hellenic League, a standard offensive and defensive alliance (symmachia), formed with 31 members under Spartan leadership. 480/79 Persian War; battles under Spartan leadership: Thermopylae (King Leonidas), Artemesium and Salamis (Eurybiades), Plataea (Pausanias), and Mycale (King Leotychides). 479 Thank-offerings dedicated at Delphi for victory over Persia including serpent column listing 31 cities faithful to “the Hellenes”. Samos, Chios, and Lesbos, and other islanders enrolled in the Hellenic League. Sparta, alarmed by the growth of Athenian power and daring, send envoys to urge the Athenians not to rebuild their walls, but Themistocles rejects the idea and tricks the envoys; Athenians rebuild walls using old statues as ‘fill’, while Themistocles is on diplomatic mission to Sparta. Following the departure of Leotychides and the Peloponnesian contingents, Xanthippus and the Athenians cross over to Sestos on the European side of the Hellespont, lay siege to the town, and capture the Persian fortress. Themistocles persuades the Athenians to complete fortifications at Piraeus, begun in 492; while Cimon promotes cooperation with Sparta, Themistocles hostile to the hegemon of the Peloponnesian and Hellenic leagues; attempts to rouse anti-Spartan feelings. -

Orestes As Fulfillment, Teraskopos and Teras

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications Classics 1985 Orestes as Fulfillment, erT askopos and Teras Deborah H. Roberts Haverford College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/classics_facpubs Repository Citation Roberts, D. H. "Orestes as Fulfillment, erT askopos and Teras," The American Journal of Philology 106 (1985) 283-297. This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORESTES AS FULFILLMENT, TERASKOPOS, AND TERAS IN THE ORESTEIA* Aeschylus' Oresteia is filled with the portentous: prophecy and prophetic vision, dream, omen, ominous speech and action.1 All these have in common a need for interpretation and a prophetic significance that expects fulfillment, and thus exemplify vividly two central and re- lated motifs of the trilogy: the persistent ambiguity of word and action and the search for a final fulfillment that will solve and settle every problem.2 At the very start of the Agamemnon, in the watchman's opening speech, we are presented with language that is obscure save to those somehow initiated in its meaning (36-39), and in the parodos we already find an uncertain wait for the final fulfillment and outcome of predictions long past. Although the Oresteia contains no single prophecy as much dis- cussed as those, for example, in the Oedipus Tyrannus and the Pro- metheus Bound, it is a trilogy (to adapt Frank Kermode's phrase) preoc- cupied with prophecy and portent.3 And the trilogy's central character plays a threefold prophetic role, for Orestes is the fulfillment of a series *An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Philological Association, San Francisco, December 1981. -

Ritual Poetics in the Plays of Sophocles

Ritual Poetics in the Plays of Sophocles by Adriana Elisabet Brook A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Adriana Brook 2014 Ritual Poetics in the Plays of Sophocles Adriana Brook Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This dissertation seeks to analyze the ritual content of the Sophoclean corpus using ritual poetics, which offers an approach to the interpretation of poetic texts based on the predictable structure and communicative properties that ritual and poetry share. In particular, drawing on the ritual theories of Arnold van Gennep and Victor Turner, as well as the dramatic theory of Aristotle, I suggest that ritual and dramatic narrative function in an analogous way in Sophocles because both advance according to a predictable progression that facilitates a change of status expressed through community membership. Due to this analogy, any deviations from the expected on the level of ritual have implications for the way in which the audience experience the plot. Sophocles, relying on his audience’s ritual competence, incorporates three kinds of discernable ritual mistakes in his plays: problems of ritual conflation, ritual repetition and ritual status. On the basis of the analogy between ritual and narrative, these ritual mistakes influence the audience’s dramatic perceptions and expectations. In the Ajax, I explore ritual conflation, showing how scenes that confuse two distinct rituals contribute to the ambivalent characterization of the protagonist, while the conflation of rituals across the play generates competing expectations about the progression of the plot.