The Mantle and Its Products - Keith Bell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3. the Crust and Upper Mantle

Theory of the Earth Don L. Anderson Chapter 3. The Crust and Upper Mantle Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications, c1989 Copyright transferred to the author September 2, 1998. You are granted permission for individual, educational, research and noncommercial reproduction, distribution, display and performance of this work in any format. Recommended citation: Anderson, Don L. Theory of the Earth. Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1989. http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechBOOK:1989.001 A scanned image of the entire book may be found at the following persistent URL: http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechBook:1989.001 Abstract: T he structure of the Earth's interior is fairly well known from seismology, and knowledge of the fine structure is improving continuously. Seismology not only provides the structure, it also provides information about the composition, crystal structure or mineralogy and physical state. In subsequent chapters I will discuss how to combine seismic with other kinds of data to constrain these properties. A recent seismological model of the Earth is shown in Figure 3-1. Earth is conventionally divided into crust, mantle and core, but each of these has subdivisions that are almost as fundamental (Table 3-1). The lower mantle is the largest subdivision, and therefore it dominates any attempt to perform major- element mass balance calculations. The crust is the smallest solid subdivision, but it has an importance far in excess of its relative size because we live on it and extract our resources from it, and, as we shall see, it contains a large fraction of the terrestrial inventory of many elements. In this and the next chapter I discuss each of the major subdivisions, starting with the crust and ending with the inner core. -

Structure of the Earth

TheThe Earth’sEarth’s StructureStructure fromfrom TravelTravel TimesTimes SphericallySpherically symmetricsymmetric structure:structure: PREMPREM --CCrustalrustal StructuStructurree --UUpperpper MantleMantle structustructurree PhasePhase transitiotransitionnss AnisotropyAnisotropy --LLowerower MantleMantle StructureStructure D”D” --SStructuretructure ofof thethe OuterOuter andand InnerInner CoreCore 3-3-DD StStructureructure ofof thethe MantleMantle fromfrom SeismicSeismic TomoTomoggrraphyaphy --UUpperpper mantlemantle -M-Miidd mmaannttllee -L-Loowweerr MMaannttllee Seismology and the Earth’s Deep Interior The Earth’s Structure SphericallySpherically SymmetricSymmetric StructureStructure ParametersParameters wwhhichich cancan bebe determineddetermined forfor aa referencereferencemodelmodel -P-P--wwaavvee v veeloloccitityy -S-S--wwaavvee v veeloloccitityy -D-Deennssitityy -A-Atttteennuuaattioionn ( (QQ)) --AAnisonisotropictropic parame parametersters -Bulk modulus K -Bulk modulus Kss --rrigidityigidity µ µ −−prepresssuresure - -ggravityravity Seismology and the Earth’s Deep Interior The Earth’s Structure PREM:PREM: velocitiesvelocities andand densitydensity PREMPREM:: PPreliminaryreliminary RReferenceeference EEartharth MMooddelel (Dziewonski(Dziewonski andand Anderson,Anderson, 1981)1981) Seismology and the Earth’s Deep Interior The Earth’s Structure PREM:PREM: AttenuationAttenuation PREMPREM:: PPreliminaryreliminary RReferenceeference EEartharth MMooddelel (Dziewonski(Dziewonski andand Anderson,Anderson, 1981)1981) Seismology and the -

INTERIOR of the EARTH / an El/EMEI^TARY Xdescrrpntion

N \ N I 1i/ / ' /' \ \ 1/ / / s v N N I ' / ' f , / X GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 / N X \ i INTERIOR OF THE EARTH / AN El/EMEI^TARY xDESCRrPNTION The Interior of the Earth An Elementary Description By Eugene C. Robertson GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 Washington 1966 United States Department of the Interior CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary Geological Survey H. William Menard, Director First printing 1966 Second printing 1967 Third printing 1969 Fourth printing 1970 Fifth printing 1972 Sixth printing 1976 Seventh printing 1980 Free on application to Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Abstract ......................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................... 1 Surface observations .............................................. 1 Openings underground in various rocks .......................... 2 Diamond pipes and salt domes .................................. 3 The crust ............................................... f ........ 4 Earthquakes and the earth's crust ............................... 4 Oceanic and continental crust .................................. 5 The mantle ...................................................... 7 The core ......................................................... 8 Earth and moon .................................................. 9 Questions and answers ............................................. 9 Suggested reading ................................................ 10 ILLUSTRATIONS -

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone

The Upper Mantle and Transition Zone Daniel J. Frost* DOI: 10.2113/GSELEMENTS.4.3.171 he upper mantle is the source of almost all magmas. It contains major body wave velocity structure, such as PREM (preliminary reference transitions in rheological and thermal behaviour that control the character Earth model) (e.g. Dziewonski and Tof plate tectonics and the style of mantle dynamics. Essential parameters Anderson 1981). in any model to describe these phenomena are the mantle’s compositional The transition zone, between 410 and thermal structure. Most samples of the mantle come from the lithosphere. and 660 km, is an excellent region Although the composition of the underlying asthenospheric mantle can be to perform such a comparison estimated, this is made difficult by the fact that this part of the mantle partially because it is free of the complex thermal and chemical structure melts and differentiates before samples ever reach the surface. The composition imparted on the shallow mantle by and conditions in the mantle at depths significantly below the lithosphere must the lithosphere and melting be interpreted from geophysical observations combined with experimental processes. It contains a number of seismic discontinuities—sharp jumps data on mineral and rock properties. Fortunately, the transition zone, which in seismic velocity, that are gener- extends from approximately 410 to 660 km, has a number of characteristic ally accepted to arise from mineral globally observed seismic properties that should ultimately place essential phase transformations (Agee 1998). These discontinuities have certain constraints on the compositional and thermal state of the mantle. features that correlate directly with characteristics of the mineral trans- KEYWORDS: seismic discontinuity, phase transformation, pyrolite, wadsleyite, ringwoodite formations, such as the proportions of the transforming minerals and the temperature at the discontinu- INTRODUCTION ity. -

LESSON PLAN from Core to Crust Craters of the Moon National Monument & Preserve

LESSON PLAN From Core to Crust Craters of the Moon National Monument & Preserve Side view of mantle and crust GRADE LEVEL: Fifth Grade-Sixth Grade SUBJECT: Earth Science, Geology DURATION: 2-3 hours GROUP SIZE: Up to 36 (6-12 breakout groups) SETTING: classroom NATIONAL/STATE STANDARDS: CCRA.SL.1 NGSS.SEP.2 KEYWORDS: stratigraphy, earth science, geology Overview Students act out different parts of the Earth and then build models of the Earth showing its layers. (CLASSROOM ACTIVITY) Objective(s) Students will be able to name the parts of the Earth. Students will understand that the Earth is dynamic. Background The Earth, like the life on its surface, is changing all the time. Parts of it are molten and slowly rise, cool, and sink back toward the Earth's core, like soup simmering over a fire. Continents drift around the globe creating the features we think of when we think of geology. But most of the Earth lies unseen between our feet and the other side of the world. The Earth is made up of the crust, the mantle, and the core. Although geologists have only drilled a few miles into the Earth's crust, they have indirectly deduced much about the remainder of the planet's composition. The Crust What we walk on and see is the crust. It is wafer thin, only 3 to 22 miles thick. If the Earth were the size of a billiard ball, the crust would be as thick as a postage stamp stuck to its surface (think how thick the membrane of life would be that coats the Earth!). -

The Mantle of Mars

The Mantle of Mars: Insights from Theory, Geophysics, High-Pressure Studies, and Meteorites Program and Abstract Volume LPI Contribution No. 1684 The Mantle of Mars: Insights from Theory, Geophysics, High-Pressure Studies, and Meteorites October 10–12, 2012 • Houston, Texas Sponsors Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute Jet Propulsion Laboratory Conveners Jim Papike University of New Mexico Charles Shearer University of New Mexico Dave Beaty Jet Propulsion Laboratory Scientific Organizing Committee Bruce Banerdt, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Dave Beaty, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lars Borg, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Linda Elkins-Tanton, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution of Washington Yingwei Fei, Geophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington Jim Papike, University of New Mexico Kevin Righter, NASA Johnson Space Center Charles Shearer, University of New Mexico Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 LPI Contribution No. 1684 Compiled in 2012 by Meeting and Publication Services Lunar and Planetary Institute USRA Houston 3600 Bay Area Boulevard, Houston TX 77058-1113 The Lunar and Planetary Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under a cooperative agreement with the Science Mission Directorate of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this volume are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. -

The Earth's Structure

THE EARTH’S STRUCTURE Geology is the study of the earth, including its structure, rocks, minerals, history, and the forces that affect it. The Earth’s surface has not always had its present form; it has changed over time. The three main layers of the Earth, the crust, mantle, and core, are all made of different materials (Figure 1). The crust is solid rock and can range in thickness from three miles (the ocean floor) to 37 miles (mountain ranges). Project Mohole, began by U.S. scientists in 1959, was designed to drill a hole all the way through the crust into the mantle. The drilling began under the Pacific Ocean, but the project ran out of money and was stopped in 1967. To date, no one has been able to get a sample of material from the mantle, but it is thought to be hotter and denser or heavier than the crust and more plastic or able to flow and change its shape under pressure. The mantle reaches 1800 miles below the crust (84% of the earth’s volume). The core contains more than 15% of the earth’s volume. Many geologists are unwilling to guess what the core is made of, but they think it must be very hot and dense. The earth’s crust is broken into several pieces called plates. These plates rest on and slide across the mantle. These plates are constantly drifting and moving the continents with them. Geologists believe that, millions of years ago, all of the continents were one huge land mass. -

Mantle Plumes and Their Record in Earth History by KC Condie

Mantle Plumes and Their Record in Earth History by K. C. Condie, 2001: Cambridge University Press, 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211 USA; hardcover, US$110, ISBN 0-521-80604-6; soft cover, US$40 ISBN 0-521-01472-7., 306 pages. This book is a synthesis of much of the work on mantle plumes that has occurred over the past 10 - 15 years. As such, the information is current and relevant to research on the origin and effects of plumes. Half of the 700 plus cited references were published in or after 1995, making this book an excellent research reference. Additionally, the text is well designed for being a usable textbook for advance undergraduates and graduate students. In essence, this book is an expanded compilation of recent publications by Condie with the addition of introductory chapters that provide a review of mantle plume hypotheses and supporting data. Although the book is geared toward igneous geochemists and petrologists, it also addresses some sedimentary topics related to the effects of plumes. The book contains nine chapters that cover most aspects of mantle plumes. The organization of the book follows a format of presenting the observational, geochemical, and experimental evidence supporting the existence of mantle plumes, followed by the more speculative hypotheses, including the role of plumes in the evolution of the earth. Chapter one presents an overview of the structure of plumes and the mantle. Chapter two discusses hotspots, including their tracks, geochemistry, and relationship to geoid highs and mantle upwellings. Chapter three covers large igneous provinces (LIPS), including those in the oceans, on the continents, and on Mars and Venus. -

Mechanisms for Lithospheric Heat Transport on Venus Implications For

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 87, NO. Btt, PAGES 9236-9246,NOVEMBER t0, 1982 Mechanismsfor Lithospheric Heat Transport on Venus' Implications for Tectonic Style and Volcanism SEAN C. SOLOMON Departmentof Earth and PlanetarySciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge,Massachusetts 02139 JAMES W. HEAD Departmentof GeologicalSciences, Brown University,Providence, Rhode Island 02912 The tectonicand volcaniccharacteristics of the surfaceof Venus are poorly known, but thesecharacter- isticsmust be closelyrelated to the mechanismby which Venus rids itself of internal heat. On the other solidplanets and satellites of thesolar system, lithospheric heat [ransport is dominatedby oneof three mechanisms:(1) plate recycling,(2) lithosphericconduction, and (3) hot spot volcanism.We evaluateeach mechanismas a candidatefor the dominantmode of lithosphericheat transferon Venus,and we explore the implicationsof eachmechanism for the interpretationof Venussurface features. Despite claims made to the contrary in the literature,plate recyclingon Venus cannot be excludedon the basisof either theoreticalarguments or presentobservations on topographyand radar backscatter.Landforms resulting from plate convergenceand divergenceon Venus would differ substantiallyfrom those on the earth becauseof the high surfacetemperature and the absenceof oceanson Venus,the lack of free or hydrated water in subductedmaterial, the possibilitythat subductionwould more commonlybe accompaniedby lithosphericdelamination, and the rapid spreadingrates that would -

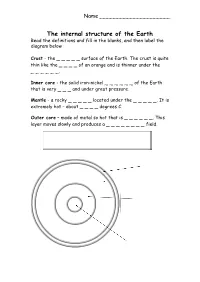

The Internal Structure of the Earth Read the Definitions and Fill in the Blanks, and Then Label the Diagram Below

Name _____________________ The internal structure of the Earth Read the definitions and fill in the blanks, and then label the diagram below Crust - the _ _ _ _ _ surface of the Earth. The crust is quite thin like the _ _ _ _ of an orange and is thinner under the _ _ _ _ _ _. Inner core - the solid iron-nickel _ _ _ _ _ _ of the Earth that is very _ _ _ and under great pressure. Mantle - a rocky _ _ _ _ _ located under the _ _ _ _ _. It is extremely hot – about _ _ _ _ degrees C. Outer core – made of metal so hot that is _ _ _ _ _ _. This layer moves slowly and produces a _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ field. outer layer oceans centre crust hot skin magnetic liquid 5000 Earth’s Structure Worksheet Use information from the following website: to color in the earth and label http://www.learner.org/interactives/dynamicearth/structure.html Earth’s Structure Worksheet Use information from the following website: http://www.learner.org/interactives/dynamicearth/structure.html Label the Layers of the Earth. Write information about each layer in the boxes below. Name: __________________________________________ Date: _______________ Inside Earth WebQuest: Worksheet Introduction: A Webquest is a way for you to explore a topic, such as “The Layers of the Earth” and find useful information to help you understand the topic. In this webquest, you will be visiting web sites that will help you better understand the Earth's interior, continental drift, plate tectonics and how these topics fit together. -

Lecture 28: the Galilean Moons of Jupiter

Lecture 28: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter Lecture 28 The Galilean Moons of Jupiter Astronomy 141 – Winter 2012 This lecture is about the Galilean Moons of Jupiter. The Galilean moons of Jupiter are heated by tides from Jupiter – closer moons are hotter. Ganymede and Callisto are old, geologically dead worlds: mostly ice mantles over rocky cores. Innermost Io is tidally melted inside, making it the most volcanically active world in the Solar System. Europa may have liquid water oceans beneath the ice, making it the most promising place to search for life. The Galilean Moons of Jupiter Io Europa Ganymede Callisto (3642 km) (3130 km) (5262 km) (4806 km) Moon (3474 km) Astronomy 141 - Winter 2012 1 Lecture 28: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter The Galilean Moons all orbit in the same direction around Jupiter. The inner 3 are on resonant orbits. Orbital Periods: Io: 1.8 days Europa Europa: 3.6 days Ganymede (2 times Io's period) Ganymede: 7.2 days Callisto (4 times Io's period) Io Callisto: 16.7 days Innermost are strongly affected by tides from Jupiter Liquid H2O @ 1atm Cold Interior Ganymede & Callisto are mixed ice & rock, low- density moons. Mean densities of 1.9 & 1.8 g/cc, respectively Deep ice mantles over rocky/icy cores. Ganymede Old, heavily cratered surfaces They lack internal heat and Callisto are geologically inactive. Astronomy 141 - Winter 2012 2 Lecture 28: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter In the terrestrial planets, interior heat is determined by the planet’s size. Large Earth & Venus have hot interiors: Smaller Mercury, Moon & Mars have cold interiors. -

The Interior of Venus

The Interior of Venus Steve Mackwell, Walter Kiefer, and Dan Nunes Lunar and Planetary Institute AGU Chapman Conference, February 2006 Observational Constraints • Radar imagery (100- 300 m/pixel) • Topography (10-30 km/pixel; vertical 16 meters RMS) • Gravity (300-400 km resolution) • Magnetic field • Limited surface and atmospheric chemistry The Crust • Composition – Plains measured by Venera landers (gamma ray spectroscopy, 5 locations; X ray fluorescence, 3 locations) – Chemistry consistent with basalt, alkali basalt (but no mineralogy measurements) – No evidence yet for felsic composition (Ishtar Terra? Tessera units?) • Mean thickness of crust in plains is 20-40 km (Grimm, 1994) The Lithosphere • Thickness of the lithosphere is much debated • Dry diabase is much stronger than wet rock (Mackwell et al., 1998) • Gravity constrains TElastic = 10–30 km (Simons et al., 1997; Barnett et al., 2000, 2002) – Implies typical mantle heat flow ~40 mW m-2 (60-90% of Earth’s mantle) • Much thicker lithosphere is problematic – How does magma escape to surface? – Very high lithospheric strength inhibits rifting Kali Mons Flexure Model 80 Observed Gravity 60 Te=30 km Te=20 km 40 20 0 -20 Free-air Gravity (mGal) Gravity Free-air -40 20 25 30 35 40 Longitude Mantle Convection Kiefer and Kellogg (1998) Mantle Convection • The convective layer thickness is 2000-3000 km. – Topographic width of Atla and Beta Regio volcanic rises – Size of region scavenged to form Ishtar Terra • Present-day convective vigor is slightly lower than on Earth. – Heat flux inferred from elastic lithosphere – Thermal Rayleigh number ~107 • Strong coupling of convective flow to surface implies no weak asthenosphere.