T. F. Torrance on the Centenary of His Birth: a Biographical and Theological Synopsis with Some Personal Reminiscences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory Acc.13559 Reverend James Watson

Acc.13559 March 2015 Inventory Acc.13559 Reverend James Watson National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-623 3876 Fax: 0131-623 3866 E-mail: [email protected] © National Library of Scotland Papers, 1894-1942, of Rev James Watson, missionary with the Baptist Missionary Society, China. Papers of Reverend James Watson (1878-1954), Baptist Missionary Society (BMS), originally from Wishaw, Lanarkshire. The papers consist mostly of Watson‟s correspondence relating to his service in China from 1906 to the 1930s, but especially concerning his experiences during the siege of Xi'an, Shaanxi province, April-November 1926. The collection also contains other papers relating to Watson and his family. The main family personalities covered by the papers are James Watson, his wife Evelyn (née Evelyn Minnie Russell), their parents, and their children John, Helen, Wreford (who went on to be a noted geographer at the University of Edinburgh), Margaret and Andrew. Some other relatives appear in the papers as correspondents or mentioned in letters. A number of leading BMS missionaries in Xi'an and elsewhere also appear as correspondents or mentioned in letters, including A.G. Shorrock, John Shields, Clement Stockley, E.L. Phillips, Frederick Russell (also brother of Evelyn), William Mudd, and Jennie Beckingsale. The mission stations, schools and hospital in Xi'an, and other mission stations in the surrounding countryside of Shaanxi province, were one of two major centres of BMS activity in China, the other being in Shandong province. The Shaanxi work began in 1890, and the BMS workers were caught up in both the Boxer Rebellion of 1900-01 (during which around 40 BMS missionaries and their families were killed in Shaanxi) and the 1911 Revolution. -

Intimations Surnames L

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames L This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames L Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage L’AMY / SCOTT 1863 Sylvester L’Amy, London, to Margaret Sinclair, 2nd daughter of John Scott, Finnart, Greenock, at St George’s, London on 6th May 1863.. see Margaret S. (Greenock Advertiser 9.5.1863) Marriage LACHLAN / 1891 Alexander McLeod to Lizzie, youngest daughter of late MCLEOD James Lachlan, at Arcade Hall, Greenock on 5th February 1891 (Greenock Telegraph 09.02.1891) Marriage LACHLAN / SLATER 1882 Peter, eldest son of John Slater, blacksmith to Mary, youngest daughter of William Lachlan formerly of Port Glasgow at 9 Plantation Place, Port Glasgow on 21.04.1882. (Greenock Telegraph 24.04.1882) see Mary L Death LACZUISKY 1869 Maximillian Maximillian Laczuisky died at 5 Clarence Street, Greenock on 26th December 1869. -

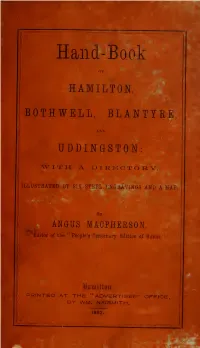

Hand-Book of Hamilton, Bothwell, Blantyre, and Uddingston. with a Directory

; Hand-Book HAMILTON, BOTHWELL, BLANTYRE, UDDINGSTON W I rP H A DIE EJ C T O R Y. ILLUSTRATED BY SIX STEEL ENGRAVINGS AND A MAP. AMUS MACPHERSON, " Editor of the People's Centenary Edition of Burns. | until ton PRINTED AT THE "ADVERTISER" OFFICE, BY WM. NAISMITH. 1862. V-* 13EFERKING- to a recent Advertisement, -*-*; in which I assert that all my Black and Coloured Cloths are Woaded—or, in other wards, based with Indigo —a process which,, permanently prevents them from assuming that brownish appearance (daily apparent on the street) which they acquire after being for a time in use. As a guarantee for what I state, I pledge myself that every piece, before being taken into stock, is subjected to a severe chemical test, which in ten seconds sets the matter at rest. I have commenced the Clothing with the fullest conviction that "what is worth doing is worth doing well," to accomplish which I shall leave " no stone untamed" to render my Establishment as much a " household word " ' for Gentlemen's Clothing as it has become for the ' Unique Shirt." I do not for a moment deny that Woaded Cloths are kept by other respectable Clothiers ; but I give the double assurance that no other is kept in my stock—a pre- caution that will, I have no doubt, ultimately serve my purpose as much as it must serve that of my Customers. Nearly 30 years' experience as a Tradesman has convinced " me of the hollowness of the Cheap" outcry ; and I do believe that most people, who, in an incautious moment, have been led away by the delusive temptation of buying ' cheap, have been experimentally taught that ' Cheapness" is not Economy. -

Fine Chinese Art New Bond Street, London I 16 May 2019

Fine Chinese Art New Bond Street, London I 16 May 2019 84 (detail) 130 (detail) Fine Chinese Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 16 May 2019 10.30am (lots 1 - 128) 2pm (lots 129 - 279) VIEWING GLOBAL HEAD, CUSTOMER SERVICES As a courtesy to intending Saturday 11 May CHINESE CERAMICS Monday to Friday 8.30am - 6pm bidders, Bonhams will provide a 11am - 5pm AND WORKS OF ART +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 written Indication of the physical Sunday 12 May Asaph Hyman condition of lots in this sale if a 11am - 5pm Please see page 4 for bidder request is received up to 24 hours before the auction starts. Monday 13 May ENQUIRIES information including after-sale 9am - 7.30pm collection and shipment This written Indication is issued Colin Sheaf subject to Clause 3 of the Notice Tuesday 14 May +44 (0) 20 7468 8237 拍賣品之狀況 to Bidders. 9am - 4.30pm [email protected] Wednesday 15 May 請注意: 本目錄並無說明任何拍賣 品之狀況。按照本目錄後部份所載 9am - 4.30pm Asaph Hyman REGISTRATION 之「競投人通告第 條 」, 準 買 家 +44 (0) 20 7468 5888 15 IMPORTANT NOTICE 必須拍賣前親自確定拍賣品之狀 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Please note that all customers, 況。 irrespective of any previous 25357 純為方便準買家,本公司如果拍買 Benedetta Mottino activity with Bonhams, are 開始前24小時收到準買家的要求, +44 (0) 20 7468 8236 required to complete the Bidder CATALOGUE 本公司可提 供 書面上的 狀 況 報 告。 [email protected] Registration Form in advance of £30.00 該報告是依據「競投人通告第1.6 條 」提 供。 the sale. The form can be found BIDS Edward Luper at the back of every catalogue +44 (0) 20 7468 5887 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 ILLUSTRATIONS and on our website at www. -

Directory of Protestant Missionaries in China, Japan and Corea

DIRECTORY OF PROTESTANT MISSIONARIES IN CHINA , JAPAN AND COREA FOR THE YEAR 1904 HONGKONG PRINTED AND PUBLISHED AT THE “ DAILY PRESS ” OFFICE 14, DES VEUX ROAD CENTRAL LONDON OFFICE : 131, FLEET STREET , E.C. MDCCCCIV PROTESTANT MISSIONARIES IN CHINA ALLGEMEINER EVANGELISCH PRO Rev. C. A. Salquist and wife (atsent ) TESTANTISCHER MISSIONSVEREIN Rev. R. Wellwood and wife ( GENERAL PROTESTANT MISSION YACHOW VIA CHUNGKING OF GERMANY) Rev. W. M. Upcraft , D.D. TSINGTAU Rev. Briton Corlies, M.D. Rev. R. Wilhelm and wife SWATOW , Rev. B Blumhardt Rev. Wm . Ashmore , D.D. , and wife (absent ) E. Dipper , M.D. Rev. S. B. Partridge, D.1 ., and wife Rev. G. H. Waters and wife AMERICAN ADVENT CHRISTIAN Mrs. A. K. Scott, M.D. MISSION Rev. Wm . Ashmore , Jr., M.A. and wife NANKING Rev. J. M. Foster, M.A. , and wife (absent) Rev. G. Howard Malone and wife ( absent ) Robert E. Worley, M.D. , and wife Miss Margaret B. Burke Miss H. L. Hyde Miss Nellie E , Dow Miss M. Sollman WUHU Miss M. F. Weld Rev. Z. Charles Beals and wife KAYIN VIA SWATOW Rev. G. E. Whitman and wife AMERICAN BAPTIST MISSIONARY Rev. S. R. Warburton and wife UNION CHAOCHOWFU VIA SWATOW HANYANG VIA HANKOW Rev. H. A. Kemp and wife Rev. J. S. Adams and wife UNGKUNG VIA SWATOW Rev. G. A. Huntley , M.D. , and wife (absent ) Rev. J. W. Carlin , D.D. , and wife Rev. Sidney G. Adams KITYANG VIA SWATOW Miss Annie L. Crowl ( absent ) Rev. Joseph Speicher and wife HANGCHOW VIA SHANGHAI Miss Josephine M. Bixby , M.D. -

1837-1849 from the Notes of John Raitt, Former Delaware County Historian

Part Two: Delaware Gazette – 1837-1849 From the notes of John Raitt, former Delaware County Historian. To help find the correct date of the event, the Delaware Gazette was published each Wednesday. Name Comment Date of Issue Abel, Elias B. Son of Elias & Betsey Abel, died aged 28 years at Franklin on Mar. 14 04/27/1842 Abbey, Stephen Of Rondout, Ulster County married Caroline Vail of Masonville in 06/23/1841 Masonville on the 15th inst by Elder Robinson Adair, Eliza Daughter of Robert Adair of Davenport on the 14th by Rev. A. Fields. All 03/27/1844 of Kortright Adams, Edward Married Pluma L. King of Hobart at Otego, Otsego Co. on the 7th inst 10/14/1846 Adams, Electa Of Otego, Otsego Co. married Lester W. Clark of Laurens, Otsego Co. at 10/14/1846 Otego on the 7th by Elder Gallup Adee, William Of Bovina married Catharine F. Reynolds of Kortright on the 29th ult by 12/05/1849 Rev. Wells Aitken, David Died suddenly at his residence in Delhi the morning of the 24th inst. 12/29/1847 Accustomed cheerfulness and conversed with his family a few minutes before his dissolution and so very sudden was the visitation that he was not even permitted to say the he felt the approach of the destroyer. Aged about 57 years Aitken, Elizabeth Wife of David C. Aitken died in Delhi on the 26th ult aged 30 years. 10/02/1844 Formerly of NY Akerly, Mariah Married John Caroll at Middletown on the 16th by Warren Dimmick, all of 01/22/1840 Middletown Akerly, Richard Of Middletown married Catherine Gregory of Andes at Andes on June 20th 07/10/1839 by Warren Dimmick Alexander, James Married Jane Murdock, of Delhi at Delhi on the 30th inst by Rev. -

Thomas F. Torrance and the Chinese Church

The missional nature of divine-human communion: Thomas F. Torrance and the Chinese church CG Seed 24135984 Thesis submitted for the degree Doctor Philosophiae in Dogmatics at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Promoter: Prof Dr DT Lioy Co-Promoter: Prof Dr PH Fick MAY 2016 PREFACE I would like to thank Professor Daniël Lioy and Professor Rikus Fick for acting as promoters for this research. Their guidance and advice the whole length of the journey has been invaluable. In addition, the administrative personnel at Greenwich School of Theology and North-West University have been a constant source of advice and encouragement, for which I am grateful. Ken Henke and his team of archivists at Princeton Theological Seminary T.F. Torrance Manuscript Collection provided professional support and a positive research environment in which to undertake the primary research. I am grateful too to the Church Mission Society for allowing me study leave in the USA and to Professor David Gregory-Smith for making the trip possible. Thanks are also due to my brother, Mark Streater and his wife Diana in Connecticut, for hosting me and providing technical back up. My husband, Rev Dr Richard Seed, has accompanied me along the academic journey, providing moral encouragement and practical support in more ways than can be documented here. I could not have completed the work without him. Thanks are also due to friends in London who offered me accommodation while I was working in the British Library, to our son Richard and his wife Jess for accommodation while I was working at Tyndale House in Cambridge. -

Area Committee Presentation Attainment and Achievement 2010

We at Oban High School believe that the school has a responsibility to ensure that all our youngsters achieve the best possible qualifications. We also believe that we need to nurture and develop their social, emotional and vocational knowledge and skills to enable them to achieve their full potential, throughout their lives. Area Committee Presentation Attainment and Achievement 2010 & 2011 1 SQA Results 2011 Initial Analysis based on Fyfe Data (August Reports) The following comments relate only to the raw data provided by Alastair Fyfe for Argyll and Bute. A more detailed report will follow when the full Fyfe Analysis is published. There are no comments relating to NCDs, Relative or Progressive Values, or comparator schools etc. at this time. Although the Fyfe data has information going back more than the usual 5 years these comments generally look at a five year trend. Green text shows data that is to be commended (within that level); red text shows results and trends that need to be addressed. NOTES Level 3 – Standard grade Foundation and Access 3 Level 4 - Standard Grade General and Intermediate 1 Level 5 – Standard Grade Credit and Intermediate 2 Level 6 – Higher Level 7 – Advanced Higher Percentages are based on the relevant S4 roll School Roll The school roll has remained steady at 1146 (1147 previous year). There were 25 more girls (160) staying on into S5/S6 than boys (135). The number of girls staying on was the highest (77) of the last eight years. 2 Cumulative Whole School Attainment By the end of S4 The percentage of pupils attaining combined English and Maths at Level 3 or above has continued to oscillate between 93% and 97%. -

Rothesay Brass Band – Entertaining the Excursionists Fresh Off the Paddle-Steamers on the Isle of Bute

Rothesay Brass Band – entertaining the excursionists fresh off the paddle-steamers on the Isle of Bute Gavin Holman, 24 February 2021 Rothesay is the main town on the Isle of Bute. It was a burgh of barony from an early period, and it became a Royal Burgh in 1400 by a charter from Robert III of Scotland. In the mid-1800’s it developed as a seaside resort, with all the features and facilities expected of such places. Sitting on an attractive bay, it quickly became popular with visitors from Glasgow and around, which having made the rail journey to Wemyss Bay, took one of the paddle-steamers across to Bute for their excursions to Rothesay, or perhaps they went "doon the watter" [the Clyde] with ships that went direct from Glasgow. Rothesay was also the location of one of Scotland's many hydropathic establishments during the 19th century boom years of the Hydropathy movement. The town also, later, had an electric tramway - the Rothesay and Ettrick Bay Light Railway - which stretched across the island to one of its largest beaches. As the town developed its tourist trade, the need for musical entertainment became clear, and a series of professional bands were engaged to supply this to the visitors in the summer months. In 1873 a bandstand was erected on the Esplanade (which would stand for nearly 40 years until being replaced in 1911) and bands would perform there on afternoons and evenings. The bandstand was gifted by Thomas Russell, who owned the large Saracen Iron Foundry in Glasgow, and who was born in Rothesay. -

Evangelicalism in Modern Scotland

EVANGELICALISM IN MODERN SCOTLAND D.W. BEBBINGTON, UNIVERSITY OF STIRLING Evangelicals can usefully be defined in terms of four characteristics. First, they are conversionist, believing that lives need to be changed by the gospel. Secondly, they are activist, holding that Christians must spread the gospel. Thirdly, they are biblicist, seeing the Bible as the authoritative source of the gospel. Fourthly, they are crucicentric in their beliefs, recognising in the atonement the focus of the gospel. Three of these four defining qualities marked Protestants in Scotland, as elsewhere, from the Reformation onwards. They were conversionist, biblicist and crucicentric. Seventeenth-century Protestants, however, were not activist in the manner of later Evangelicals. Typically they wrestled with doubts and fears about their own salvation rather than confidently announcing the way of salvation to those outside their sphere. Hence, for instance, there was a remarkable paucity of Protestant missionary work during the seventeenth century. But from the eighteenth century onwards an Evangelical movement sprang into existence in Scotland and elsewhere in the English-speaking world. Its activism marked it out from the Protestant tradition that had preceded it. Evangelicalism was a creation of the eighteenth century. The customary view of the Church of Scotland in the eighteenth century divides it into two parties. The Moderates are usually described as liberal in theology, scholarly in disposition and strongly attached to patronage. The Popular Party is held to have been conservative in theology, unfavourable to contemporary learning and opposed to patronage. Increasingly, however, it has become apparent that the model does not correspond with reality. Some ministers who were theologically conservative nevertheless favoured patronage. -

Theology in Transposition Know His Theology Is to Know Him, and Vice Versa

1 Who Is Thomas Forsyth Torrance? Professor Thomas Forsyth Torrance—TF to his students (to distinguish him from his brother JB), or Tom to those who knew him—was a towering figure in twentieth century theology. His prodigious literary output, translation work, edited volumes, international speaking engagements, and ecclesiastical and ecumenical endeavors cast a huge influence over theology and theologians working with him, against him, and after him. Now in the twenty-first century the impact of his work is still being felt as PhDs are completed on his work, monographs roll off the presses detailing and critiquing aspects of his theology, and societies and even entire denominations are established to disseminate central features of his thought.1 Clearly, the theology of Thomas Torrance, his method and content, continues to be of interest today, and for good reason. To introduce Torrance (1913–2007), a full biography of the man and his life is not in order. Alister McGrath has done an admirable job in providing the interested reader with an intellectual biography.2 However, given Torrance’s axiom that to know God we must know God in God’s act and being, it seems appropriate to apply the same methodology to our exploration of Torrance: to 1. I am referring specifically to the Thomas Torrance Theological Fellowship and its theological journal, , and Grace Communion International, formerly the Worldwide Church of God, Participatio which has adopted Torrance’s Trinitarian theology as the basis of its own theological trajectory. 2. Alister E. McGrath, (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1999). A very T. F. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 10/02/2010, 10:30

Public Document Pack Argyll and Bute Council Comhairle Earra Ghaidheal agus Bhoid Corporate Services Director: Nigel Stewart Lorn House, Albany Street, Oban, Argyll, PA34 4AR Tel: 01631 567901 Fax: 01631 570379 2 March 2010 NOTICE OF MEETING A meeting of the OBAN LORN & THE ISLES AREA COMMITTEE will be held in the MCCAIG SUITE, CORRAN HALLS, OBAN on WEDNESDAY, 10 FEBRUARY 2010 at 10:30 AM , which you are requested to attend. Nigel Stewart Director of Corporate Services BUSINESS 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 3. CORPORATE SERVICES (a) Minutes of meeting of Oban Lorn & the Isles Area Committee held on 2nd December 2009 (Pages 1 - 6) (b) Oban Lorn & the Isles Area Plan (Draft) (Pages 7 - 12) 4. COMMUNITY SERVICES (a) Applications for financial assistance under the Education Development Grants Scheme (Pages 13 - 44) (b) Applications for financial assistance under the Leisure Development Grants Scheme (Pages 45 - 46) (c) Applications for financial assistance under the Social Welfare Grants Scheme (Pages 47 - 64) (d) Oban High School Achievement Report (Pages 65 - 142) 5. DEVELOPMENT SERVICES (a) Proposed Mull Landscape Capacity Study (Pages 143 - 146) (b) Draft response to the public consultation on the Draft Marine Spatial Plan for the Sound of Mull (Pages 147 - 152) 6. PUBLIC QUESTION TIME The Committee will be asked to pass a resolution in terms of Section 50(a)94) of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 to exclude the public for items of business with an “E” on the grounds that it is likely to involve the disclosure of exempt information as defined in the appropriate paragraph of Part 1 of Schedule 7a to the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973.