Analysis of the Human Breast Milk Microbiome and Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Healthy Mothers Su Yeong Kim1 and Dae Yong Yi 1,2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of the Aerobic Anoxygenic Phototrophic Bacterium Sphingomonas Sp

microorganisms Article Characterization of the Aerobic Anoxygenic Phototrophic Bacterium Sphingomonas sp. AAP5 Karel Kopejtka 1 , Yonghui Zeng 1,2, David Kaftan 1,3 , Vadim Selyanin 1, Zdenko Gardian 3,4 , Jürgen Tomasch 5,† , Ruben Sommaruga 6 and Michal Koblížek 1,* 1 Centre Algatech, Institute of Microbiology, Czech Academy of Sciences, 379 81 Tˇreboˇn,Czech Republic; [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (V.S.) 2 Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Thorvaldsensvej 40, 1871 Frederiksberg C, Denmark 3 Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, 370 05 Ceskˇ é Budˇejovice,Czech Republic; [email protected] 4 Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre, Czech Academy of Sciences, 370 05 Ceskˇ é Budˇejovice,Czech Republic 5 Research Group Microbial Communication, Technical University of Braunschweig, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany; [email protected] 6 Laboratory of Aquatic Photobiology and Plankton Ecology, Department of Ecology, University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Present Address: Department of Molecular Bacteriology, Helmholtz-Centre for Infection Research, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany. Abstract: An aerobic, yellow-pigmented, bacteriochlorophyll a-producing strain, designated AAP5 Citation: Kopejtka, K.; Zeng, Y.; (=DSM 111157=CCUG 74776), was isolated from the alpine lake Gossenköllesee located in the Ty- Kaftan, D.; Selyanin, V.; Gardian, Z.; rolean Alps, Austria. Here, we report its description and polyphasic characterization. Phylogenetic Tomasch, J.; Sommaruga, R.; Koblížek, analysis of the 16S rRNA gene showed that strain AAP5 belongs to the bacterial genus Sphingomonas M. Characterization of the Aerobic and has the highest pairwise 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with Sphingomonas glacialis (98.3%), Anoxygenic Phototrophic Bacterium Sphingomonas psychrolutea (96.8%), and Sphingomonas melonis (96.5%). -

The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio In

microorganisms Review The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease Spase Stojanov 1,2, Aleš Berlec 1,2 and Borut Štrukelj 1,2,* 1 Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Biotechnology, Jožef Stefan Institute, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia * Correspondence: borut.strukelj@ffa.uni-lj.si Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 31 October 2020; Published: 1 November 2020 Abstract: The two most important bacterial phyla in the gastrointestinal tract, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, have gained much attention in recent years. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio is widely accepted to have an important influence in maintaining normal intestinal homeostasis. Increased or decreased F/B ratio is regarded as dysbiosis, whereby the former is usually observed with obesity, and the latter with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Probiotics as live microorganisms can confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. There is considerable evidence of their nutritional and immunosuppressive properties including reports that elucidate the association of probiotics with the F/B ratio, obesity, and IBD. Orally administered probiotics can contribute to the restoration of dysbiotic microbiota and to the prevention of obesity or IBD. However, as the effects of different probiotics on the F/B ratio differ, selecting the appropriate species or mixture is crucial. The most commonly tested probiotics for modifying the F/B ratio and treating obesity and IBD are from the genus Lactobacillus. In this paper, we review the effects of probiotics on the F/B ratio that lead to weight loss or immunosuppression. -

Altered Fecal Microbiota Composition in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 48 (2015) 186–194 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Brain, Behavior, and Immunity journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ybrbi Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder Haiyin Jiang a,1, Zongxin Ling a,1, Yonghua Zhang b,1, Hongjin Mao c, Zhanping Ma d, Yan Yin c, ⇑ Weihong Wang e, Wenxin Tang c, Zhonglin Tan c, Jianfei Shi c, Lanjuan Li a,2, Bing Ruan a, a Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310003, China b Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Seventh People’s Hospital of Hangzhou, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310003, China c Department of Psychiatry, The Seventh People’s Hospital of Hangzhou, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310003, China d Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Hospital of Hengshui, Hebei 053000, China e Department of Infectious Diseases, Huzhou Central Hospital, Huzhou, Zhejiang 313000, China article info abstract Article history: Studies using animal models have shown that depression affects the stability of the microbiota, but the Received 29 July 2014 actual structure and composition in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) are not well under- Received in revised form 29 March 2015 stood. Here, we analyzed fecal samples from 46 patients with depression (29 active-MDD and 17 Accepted 29 March 2015 responded-MDD) and 30 healthy controls (HCs). High-throughput pyrosequencing showed that, accord- Available online 13 April 2015 ing to the Shannon index, increased fecal bacterial a-diversity was found in the active-MDD (A-MDD) vs. -

The Oral Microbiome of Healthy Japanese People at the Age of 90

applied sciences Article The Oral Microbiome of Healthy Japanese People at the Age of 90 Yoshiaki Nomura 1,* , Erika Kakuta 2, Noboru Kaneko 3, Kaname Nohno 3, Akihiro Yoshihara 4 and Nobuhiro Hanada 1 1 Department of Translational Research, Tsurumi University School of Dental Medicine, Kanagawa 230-8501, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Oral bacteriology, Tsurumi University School of Dental Medicine, Kanagawa 230-8501, Japan; [email protected] 3 Division of Preventive Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry and Graduate School of Medical and Dental Science, Niigata University, Niigata 951-8514, Japan; [email protected] (N.K.); [email protected] (K.N.) 4 Division of Oral Science for Health Promotion, Faculty of Dentistry and Graduate School of Medical and Dental Science, Niigata University, Niigata 951-8514, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-45-580-8462 Received: 19 August 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020; Published: 16 September 2020 Abstract: For a healthy oral cavity, maintaining a healthy microbiome is essential. However, data on healthy microbiomes are not sufficient. To determine the nature of the core microbiome, the oral-microbiome structure was analyzed using pyrosequencing data. Saliva samples were obtained from healthy 90-year-old participants who attended the 20-year follow-up Niigata cohort study. A total of 85 people participated in the health checkups. The study population consisted of 40 male and 45 female participants. Stimulated saliva samples were obtained by chewing paraffin wax for 5 min. The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene were amplified by PCR. -

Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis David Johane Machate 1, Priscila Silva Figueiredo 2 , Gabriela Marcelino 2 , Rita de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães 2,*, Priscila Aiko Hiane 2 , Danielle Bogo 2, Verônica Assalin Zorgetto Pinheiro 2, Lincoln Carlos Silva de Oliveira 3 and Arnildo Pott 1 1 Graduate Program in Biotechnology and Biodiversity in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] (D.J.M.); [email protected] (A.P.) 2 Graduate Program in Health and Development in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; pri.fi[email protected] (P.S.F.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (P.A.H.); [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (V.A.Z.P.) 3 Chemistry Institute, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-67-3345-7416 Received: 9 March 2020; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 8 June 2020 Abstract: Long-term high-fat dietary intake plays a crucial role in the composition of gut microbiota in animal models and human subjects, which affect directly short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and host health. This review aims to highlight the interplay of fatty acid (FA) intake and gut microbiota composition and its interaction with hosts in health promotion and obesity prevention and its related metabolic dysbiosis. -

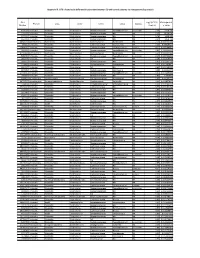

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Changes in the Bacterial Diversity of Human Milk During Late Lactation Period (Weeks 21 to 48)

foods Communication Changes in the Bacterial Diversity of Human Milk during Late Lactation Period (Weeks 21 to 48) Wendy Marin-Gómez ,Ma José Grande, Rubén Pérez-Pulido, Antonio Galvez * and Rosario Lucas Microbiology Division, Department of Health Sciences, Faculty of Experimental Sciences, University of Jaén, 23071 Jaén, Spain; [email protected] (W.M.-G.); [email protected] (M.J.G.); [email protected] (R.P.-P.); [email protected] (R.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-953-212160 Received: 19 July 2020; Accepted: 25 August 2020; Published: 27 August 2020 Abstract: Breast milk from a single mother was collected during a 28-week lactation period. Bacterial diversity was studied by amplicon sequencing analysis of the V3-V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene. Firmicutes and Proteobacteria were the main phyla detected in the milk samples, followed by Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes. The proportion of Firmicutes to Proteobacteria changed considerably depending on the sampling week. A total of 411 genera or higher taxons were detected in the set of samples. Genus Streptococcus was detected during the 28-week sampling period, at relative abundances between 2.0% and 68.8%, and it was the most abundant group in 14 of the samples. Carnobacterium and Lactobacillus had low relative abundances. At the genus level, bacterial diversity changed considerably at certain weeks within the studied period. The weeks or periods with lowest relative abundance of Streptococcus had more diverse bacterial compositions including genera belonging to Proteobacteria that were poorly represented in the rest of the samples. Keywords: breast milk; biodiversity; lactic acid bacteria; late lactation; metagenomics 1. -

Microbial Strain-Level Population Structure and Genetic Diversity from Metagenomes

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 1, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Method Microbial strain-level population structure and genetic diversity from metagenomes Duy Tin Truong,1 Adrian Tett,1 Edoardo Pasolli,1 Curtis Huttenhower,2,3 and Nicola Segata1 1Centre for Integrative Biology, University of Trento, 38123 Trento, Italy; 2Biostatistics Department, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA; 3The Broad Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA Among the human health conditions linked to microbial communities, phenotypes are often associated with only a subset of strains within causal microbial groups. Although it has been critical for decades in microbial physiology to characterize individual strains, this has been challenging when using culture-independent high-throughput metagenomics. We introduce StrainPhlAn, a novel metagenomic strain identification approach, and apply it to characterize the genetic structure of thou- sands of strains from more than 125 species in more than 1500 gut metagenomes drawn from populations spanning North and South American, European, Asian, and African countries. The method relies on per-sample dominant sequence variant reconstruction within species-specific marker genes. It identified primarily subject-specific strain variants (<5% inter-subject strain sharing), and we determined that a single strain typically dominated each species and was retained over time (for >70% of species). Microbial population structure was correlated in several distinct ways with the geographic structure of the host population. In some cases, discrete subspecies (e.g., for Eubacterium rectale and Prevotella copri) or continuous mi- crobial genetic variations (e.g., for Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) were associated with geographically distinct human populations, whereas few strains occurred in multiple unrelated cohorts. -

Bacteroides Fragilis Group Is on the Fast Track to Resistance

antibiotics Article Surveillance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Anaerobe Clinical Isolates in Southeast Austria: Bacteroides fragilis Group Is on the Fast Track to Resistance Elisabeth König 1,2, Hans P. Ziegler 1, Julia Tribus 1, Andrea J. Grisold 1 , Gebhard Feierl 1 and Eva Leitner 1,* 1 Diagnostic & Research Institute of Hygiene, Microbiology and Environmental Medicine, Medical University of Graz, A 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] (E.K.); [email protected] (H.P.Z.); [email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] (A.J.G.); [email protected] (G.F.) 2 Section of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University of Graz, A 8010 Graz, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Anaerobic bacteria play an important role in human infections. Bacteroides spp. are some of the 15 most common pathogens causing nosocomial infections. We present antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) results of 114 Gram-positive anaerobic isolates and 110 Bacteroides-fragilis- group-isolates (BFGI). Resistance profiles were determined by MIC gradient testing. Furthermore, we performed disk diffusion testing of BFGI and compared the results of the two methods. Within Gram-positive anaerobes, the highest resistance rates were found for clindamycin and moxifloxacin Citation: König, E.; Ziegler, H.P.; (21.9% and 16.7%, respectively), and resistance for beta-lactams and metronidazole was low (<1%). Tribus, J.; Grisold, A.J.; Feierl, G.; For BFGI, the highest resistance rates were also detected for clindamycin and moxifloxacin (50.9% and Leitner, E. Surveillance of 36.4%, respectively). Resistance rates for piperacillin/tazobactam and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid Antimicrobial Susceptibility of were 10% and 7.3%, respectively. -

The Human Microbiome and Its Link in Prostate Cancer Risk and Pathogenesis Paul Katongole1,2* , Obondo J

Katongole et al. Infectious Agents and Cancer (2020) 15:53 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-020-00319-2 REVIEW Open Access The human microbiome and its link in prostate cancer risk and pathogenesis Paul Katongole1,2* , Obondo J. Sande3, Moses Joloba3, Steven J. Reynolds4 and Nixon Niyonzima5 Abstract There is growing evidence of the microbiome’s role in human health and disease since the human microbiome project. The microbiome plays a vital role in influencing cancer risk and pathogenesis. Several studies indicate microbial pathogens to account for over 15–20% of all cancers. Furthermore, the interaction of the microbiota, especially the gut microbiota in influencing response to chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy remains an area of active research. Certain microbial species have been linked to the improved clinical outcome when on different cancer therapies. The recent discovery of the urinary microbiome has enabled the study to understand its connection to genitourinary malignancies, especially prostate cancer. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in males worldwide. Therefore research into understanding the factors and mechanisms associated with prostate cancer etiology, pathogenesis, and disease progression is of utmost importance. In this review, we explore the current literature concerning the link between the gut and urinary microbiome and prostate cancer risk and pathogenesis. Keywords: Prostate cancer, Microbiota, Microbiome, Gut microbiome, And urinary microbiome Introduction by which the microbiota can alter cancer risk and pro- The human microbiota plays a vital role in many life gression are primarily attributed to immune system processes, both in health and disease [1, 2]. The micro- modulation through mediators of chronic inflammation. -

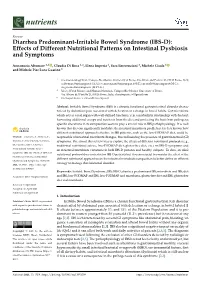

Diarrhea Predominant-Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D): Effects of Different Nutritional Patterns on Intestinal Dysbiosis and Symptoms

nutrients Review Diarrhea Predominant-Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D): Effects of Different Nutritional Patterns on Intestinal Dysbiosis and Symptoms Annamaria Altomare 1,2 , Claudia Di Rosa 2,*, Elena Imperia 2, Sara Emerenziani 1, Michele Cicala 1 and Michele Pier Luca Guarino 1 1 Gastroenterology Unit, Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome, Via Álvaro del Portillo 21, 00128 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (S.E.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.P.L.G.) 2 Unit of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome, Via Álvaro del Portillo 21, 00128 Rome, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder charac- terized by abdominal pain associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits. Gut microbiota, which acts as a real organ with well-defined functions, is in a mutualistic relationship with the host, harvesting additional energy and nutrients from the diet and protecting the host from pathogens; specific alterations in its composition seem to play a crucial role in IBS pathophysiology. It is well known that diet can significantly modulate the intestinal microbiota profile but it is less known how different nutritional approach effective in IBS patients, such as the low-FODMAP diet, could be Citation: Altomare, A.; Di Rosa, C.; responsible of intestinal microbiota changes, thus influencing the presence of gastrointestinal (GI) Imperia, E.; Emerenziani, S.; Cicala, symptoms. The aim of this review was to explore the effects of different nutritional protocols (e.g., M.; Guarino, M.P.L. -

Sphingomonas Sp. Cra20 Increases Plant Growth Rate and Alters Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure of Arabidopsis Thaliana Under Drought Stress

fmicb-10-01221 June 4, 2019 Time: 15:3 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 05 June 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01221 Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 Increases Plant Growth Rate and Alters Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure of Arabidopsis thaliana Under Drought Stress Yang Luo1, Fang Wang1, Yaolong Huang1, Meng Zhou1, Jiangli Gao1, Taozhe Yan1, Hongmei Sheng1* and Lizhe An1,2* 1 Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Cell Activities and Stress Adaptations, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2 The College of Forestry, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China The rhizosphere is colonized by a mass of microbes, including bacteria capable of Edited by: promoting plant growth that carry out complex interactions. Here, by using a sterile Camille Eichelberger Granada, experimental system, we demonstrate that Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 promotes the University of Taquari Valley, Brazil growth of Arabidopsis thaliana by driving developmental plasticity in the roots, thus Reviewed by: Muhammad Saleem, stimulating the growth of lateral roots and root hairs. By investigating the growth Alabama State University, dynamics of A. thaliana in soil with different water-content, we demonstrate that Cra20 United States Andrew Gloss, increases the growth rate of plants, but does not change the time of reproductive The University of Chicago, transition under well-water condition. The results further show that the application of United States Cra20 changes the rhizosphere indigenous bacterial community, which may be due *Correspondence: to the change in root structure. Our findings provide new insights into the complex Hongmei Sheng [email protected] mechanisms of plant and bacterial interactions. The ability to promote the growth of Lizhe An plants under water-deficit can contribute to the development of sustainable agriculture.