Armenia Opinion on the Constitutional Implications of the Ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strasbourg, 3 September 2003 MIN-LANG/PR (2003) 7 Initial Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General of the Council Of

Strasbourg, 3 September 2003 MIN-LANG/PR (2003) 7 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Initial Periodical Report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter ARMENIA The First Report of the Republic of Armenia According to Paragraph 1 of Article 15 of European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages June 2003, Yerevan 2 INTRODUCTION The Republic of Armenia signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages on May 11, 2001. In respect of Armenia the Charter has come into force since May 1, 2002. The RA introduces the following report according to Paragraph 1 of Article 15 of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. This report has been elaborated and developed by the State Language Board at the Ministry of Education and Science based on the information submitted by the relevant ministries NGOs and administrative offices, taking into consideration the remarks and suggestions made by them and all parties interested, while discussing the following report. PART I Historical Outline Being one of the oldest countries in the world, for the first time in its new history Armenia regained its independence on May 28, 1918. The first Republic existed till November 29, 1920, when Armenia after forced sovetalization joined the Soviet Union, becoming on of the 15 republics. As a result of referendum the Republic of Armenia revived its independence on September 21, 1991. Armenia covers an area of 29,8 thousand km2, the population is nearly 32000001. Armenia borders on Iran, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Turkey. -

Armenia: a Human Rights Perspective for Peace and Democracy

6OJWFSTJU´U1PUTEBN "OKB.JIS]"SUVS.LSUJDIZBO]$MBVEJB.BIMFS]3FFUUB5PJWBOFO &ET "SNFOJB")VNBO3JHIUT1FSTQFDUJWF GPS1FBDFBOE%FNPDSBDZ )VNBO3JHIUT )VNBO3JHIUT&EVDBUJPOBOE.JOPSJUJFT Armenia: A Human Rights Perspective for Peace and Democracy Human Rights, Human Rights Education and Minorities Edited by Anja Mihr Artur Mkrtichyan Claudia Mahler Reetta Toivanen Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2005 Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. © Universität Potsdam, 2005 Herausgeber: MenschenRechtsZentrum der Universität Potsdam Vertrieb: Universitätsverlag Potsdam Postfach 60 15 53, 14415 Potsdam Fon +49 (0) 331 977 4517 / Fax 4625 e-mail: [email protected] http://info.ub.uni-potsdam.de/verlag.htm Druck: Audiovisuelles Zentrum der Universität Potsdam und sd:k Satz Druck GmbH Teltow ISBN 3-937786-66-X Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Es darf ohne vorherige Genehmigung der Herausgeber nicht vervielfältigt werden. This book is published with the financial support of the Volkswagen Stiftung -Tandem Project Berlin/ Potsdam, Germany. The publication can be downloaded as PDF-file under: www.humanrightsresearch.de An Armenian version of the publication which includes papers of the con- ference and carries the title “Armenia from the perspective of Human Rights” was published by the Yerevan State University in Armenia in Au- gust 2005 and made possible through -

Materials of Conference Devoted to 80 Anniversary

YEREVAN STATE UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF LAW MATERIALS OF CONFERENCE DEVOTED TO 80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FACULTY OF LAW OF THE YEREVAN STATE UNIVERSITY Yerevan YSU Press 2014 UDC 340(479.25) Editorial board Gagik Ghazinyan Editor in Chief, Dean of the Faculty of Law, Yerevan State University, Corresponding member of the RA National Academy of Sciences, Doctor of Legal Sciences, Professor Armen Haykyants Doctor of Legal Sciences, Professor of the Chair of Civil Law of the Yerevan State University Yeghishe Kirakosyan Candidate of Legal Sciences, Docent of the Chair of European and International Law of the Yerevan State University, Adviser to the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Armenia The present publication includes reports presented during the Conference devoted to the 80th Anniversary of the Law Department of Yerevan State University. Articles relate to different fields of jurisprudence and represent the main line of legal thought in Armenia. Authors of the articles are the members of the faculty of the Law Department of Yerevan State University. The present volume can be useful for legal scholars, legal professionals, Ph.D. students, as well as others, who are interested in different legal issues relating to the legal system of Armenia. ISBN 978-5-8084-1903-2 © YSU Press, 2014 2 Contents Artur Vagharshyan ISSUES OF LEGAL REGULATION OF FILLING THE GAPS OF POSITIVE LAW IN THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA ....................... 9 Taron Simonyan NASH EQUILIBRIUM AS A MEAN FOR DETERMINATION OF RULES OF LAW (FOR SOVEREIGN ACTORS) ............................ 17 Alvard Aleksanyan YEZNIK KOGHBATSI’S LEGAL VIEWS ...................................... 25 Sergey Kocharyan PRINCIPLE OF LEGAL LEGITIMACY IN THE PHASE SYSTEM OF LEGAL REGULATION MECHANISM .......................................... -

Draft Law of the Republic of Armenia “On Ensuring Equality”

Draft Law of the Republic of Armenia “On Ensuring Equality” Legislative Analysis London, March 2018 Analysis About the Equal Rights Trust The Equal Rights Trust is an independent international organisation whose objective is to combat discrimination and advance equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. We pursue and promote the right to equality as a right to participate in all areas of life on an equal basis, which requires taking a holistic, comprehensive approach to different inequalities. Since our foundation, this approach has provided the conceptual basis for all our work, which focuses on how to achieve equality through the enactment and implementation of equality law. Contact The Equal Rights Trust 314 - 320 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8DP United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7610 2786 www.equalrightstrust.org [email protected] 2 Legislative Analysis of the Draft Law of the Republic of Armenia “On Ensuring Equality” Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 PART 1: SUBSTANTIVE ELEMENTS OF EQUALITY LAW ................................................................................. 5 Article 1: Purpose ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Article 3: Prohibition of Discrimination ............................................................................................................ -

Mise En Page 1

EURO-ASIA ARMENIA UNITARY COUNTRY BASIC SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS INCOME GROUP: UPPER MIDDLE INCOME LOCAL CURRENCY: ARMENIAN DRAM (AMD) POPULATION AND GEOGRAPHY ECONOMIC DATA Area: 29 740 km 2 GDP: 28.3 billion (current PPP international dollars), i.e. 9 668 dollars per inhabitant Population: 2.930 million inhabitants (2017), an increase of 0.3 % (2017) per year (2010-2015) Real GDP growth: 7.5 % (2017 vs 2016) Density: 98.5 inhabitants / km 2 Unemployment rate: 17.8 % (2017) Urban population: 63.1% of national population Foreign direct investment, net inflows (FDI): 250 (BoP, current USD millions, 2017) Urban population growth: 0.2% (2017 vs 2016) Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF): 17.3 % of GDP (2017) Capital city: Yerevan (36.9% of national population) HDI: 0.755 (high), rank 83 (2017) Poverty rate: 1.4% (2017) MAIN FEATURES OF THE MULTI-LEVEL GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK According to its Constitution, adopted in 1995, Armenia is a unitary state. Amendments to the Constitution in 2015 changed the form of government from a presidential republic to a parliamentary one. The legislative power is vested in a unicameral Parliament, the National Assembly, which consists of at least 101 representatives elected by proportional suffrage for five years. The new Constitution also provides for the allocation of four seats in the National Assembly to representatives of national minorities, one each from the country’s Assyrian, Kurdish, Russian and Yezidi communities. The President of the Republic is the head of the state and is elected by the National Assembly for a non-renewable term of seven years. The President appoints as Prime Minister the candidate nominated by the parliamentary majority in the National Assembly. -

Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Strasbourg, 13 February 2017 ACFC/OP/IV(2016)006 Fourth Opinion on Armenia adopted on 26 May 2016 Summary A climate of tolerance and dialogue between the majority population and national minority groups generally prevails in the Republic of Armenia. Socio-economic difficulties continue to affect significantly a large part of the population of the country, in particular in secluded mountainous areas where a large proportion of persons belonging to national minorities live. However, in spite of economic difficulties, Armenia recently admitted over 20 000 persons who were fleeing the conflict in Syria. The authorities work to ensure the protection of national minorities and provide some opportunities for learning the Assyrian, Kurdish, Russian and Yezidi languages in schools. Constitutional amendments, adopted in 2015, have altered the legislative framework affecting national minorities. The new Electoral Code, currently under consideration in the National Assembly, is to provide for parliamentary representation for the four largest national minorities in the country. Other significant changes are likely to result from the forthcoming enactment of the Law on the Prohibition of Discrimination and the Law on National Minorities, which is called for under the revised constitution. Newspapers and magazines in languages of national minorities continue to be published and the public radio broadcasts in minority languages. Support is provided to the artistic expressions of national minorities. However, the majority of cultural initiatives, although praiseworthy in themselves, tend to present a folkloristic picture of national minorities. Progress has been achieved in providing access to preschool education, although significant efforts are needed to meet the goal of the 90% rate for preschool enrolment by the deadline of 2017, as set by the government. -

<Div Style="Position:Absolute;Top:293;Left

RA MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE YEREVAN STATE LINGUISTIC UNIVERSITY AFTER V. BRUSOV LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT ARMENIA YEREVAN 2008 The report was prepared within the framework of Armenia-Council of Europe cooperation The group was established by the order of the RA Minister of Education and Science (N 210311/1012, 05.11.2007) Members of the working group Souren Zolyan – Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor Yerevan Brusov State Linguistic University (YSLU), Rector, National overall coordinator, consultant Melanya Astvatsatryan– Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences, Professor YSLU, Head of the Chair of Pedagogy and Foreign Language Methodology Project Director (Chapters 1-3; 5; 10; 12) Aida Topuzyan – Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Docent YSLU, Chair of Pedagogy and Foreign Language Methodology (Chapter 8.2 – 8.5, 9.4) Nerses Gevorgyan – Ministry of Education and Science, YSLU, UNESCO Chair on Education Management and Planning (Chapter 11), Head of Chair Gayane Terzyan - YSLU, Chair of Pedagogy and Foreign Language Methodology (Chapters 4; 6; 7; 8.1) Serob Khachatryan – National Institute for Education, Department of Armenology and Socio-cultural Subjects (Chapter 9.1-9.3, 9.5-9.6) Karen Melkonyan, RA MES, Centre for Educational Programmes, Project expert Araik Jraghatspanyan – YSLU, Chair of English Communication, Project translator Bella Ayunts – YSLU, Chair of Pedagogy and Foreign Language Methodology, Project assistant LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY PROFILE COUNTRY REPORT - ARMENIA I. GENERAL INFORMATION 1. PROJECT GOALS 2. COUNCIL OF EUROPE LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY: GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND PRINCIPLES 3. REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA General information 3.1. Geographical position 3.2. RA administrative division 3.3. Demographic data 4. -

Assemblée Générale Distr

Nations Unies A/HRC/16/44/Add.2 Assemblée générale Distr. générale 23 décembre 2010 Français Original: anglais Conseil des droits de l’homme Seizième session Point 3 de l’ordre du jour Promotion et protection de tous les droits de l’homme, civils, politiques, économiques, sociaux et culturels, y compris le droit au développement Rapport de la Rapporteuse spéciale sur la situation des défenseurs des droits de l’homme, Margaret Sekaggya Additif Mission en Arménie* Résumé Du 12 au 18 juin 2010, la Rapporteuse spéciale sur la situation des défenseurs des droits de l’homme a effectué une visite en Arménie, où elle s’est entretenue avec de hauts responsables de l’État et des défenseurs des droits de l’homme d’horizons divers. Cette visite avait pour but d’évaluer la situation des défenseurs des droits de l’homme en Arménie à la lumière des principes énoncés dans la Déclaration sur le droit et la responsabilité des individus, groupes et organes de la société de promouvoir et de protéger les droits de l’homme et les libertés fondamentales universellement reconnus (Déclaration sur les défenseurs des droits de l’homme). Après un chapitre d’introduction, la Rapporteuse présente, dans le chapitre II, le contexte général dans lequel les défenseurs des droits de l’homme exercent leurs activités en Arménie. La société civile, et notamment les défenseurs des droits de l’homme, exercent leurs fonctions dans un environnement de plus en plus politisé et rares sont les acteurs qui n’ont pas été touchés par les divisions politiques de ces dernières années, en particulier au lendemain des événements de 2008. -

Elections in Armenia: 2021 Early Parliamentary Elections Frequently Asked Questions

Elections in Armenia 2021 Early Parliamentary Elections Frequently Asked Questions Europe and Eurasia International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive | Floor 10 | Arlington, VA 22202 | USA | www.IFES.org June 15, 2021 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? .............................................................................................................................. 1 Who are citizens voting for on Election Day? ........................................................................................ 1 Why are early elections being called? .................................................................................................... 1 What is Armenia’s electoral system? ...................................................................................................... 1 What is Armenia’s election management body? ................................................................................... 2 Who can vote in these elections? ............................................................................................................ 2 What provisions are in place to guarantee equal access to the electoral process for persons with disabilities? .................................................................................................................................................. 3 How is the election management body protecting the elections and voters from COVID-19? ...... 3 Who can observe during Election Day? How can they get accreditation? ....................................... -

Implementation by Armenia of Assembly Resolutions 1609 (2008) and 1620 (2008)

Doc. 11786 22 December 2008 Implementation by Armenia of Assembly Resolutions 1609 (2008) and 1620 (2008) Report Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the Council of Europe (Monitoring Committee) Co-rapporteurs: Mr Georges COLOMBIER, France, Group of the European People’s Party and Mr John PRESCOTT, United Kingdom, Socialist Group Summary In relation to the implementation by Armenia of Assembly Resolutions 1609 (2008) and 1620 (2008), the committee welcomed the establishment, by presidential decree, of an expert fact-finding group to inquire into the events of 1 and 2 March 2008 and the circumstances that led to them. The establishment of this group, in which both opposition and authorities have nominated experts, was considered an important step regarding the Assembly demand that an impartial and transparent investigation into these events be established, but the committee cautioned that, in the end, it will be the manner in which this group will conduct its work that will determine its credibility in the eyes of the Armenian public. However, the committee was seriously concerned about the limited progress achieved with regard to the demands of the Assembly concerning the persons deprived of their liberty in relation to the events of 1 and 2 March 2008, especially concerning those charged under Articles 225 and 300 of the Criminal Code of Armenia, and prosecution cases based solely on police testimony without substantial corroborating evidence. In addition, the committee regretted that the authorities had not availed themselves of the opportunity to resolve this issue through all legal means available to them, such as amnesty, pardons and the dropping of charges, as suggested by the Assembly. -

FAIFE World Report: Armenia

Population: 3,344,336 (2000) Armenia declared independence in 1991 September. Although after the GNP per capita: $2,900 (1999) collapse of the USSR until 1996 the Armenian libraries continued to Government / Constitution: Republic operate under the centrally controlled system of management. During the Main languages: Armenian (93%), Russian, Kurd pervious regime libraries were united into the so-called Centralized Main religions: Armenian Orthodox Library System (CLS) which envisaged a central library with its Literacy: 99% (1999) dependent branches, under the Ministry of Culture. The number of the Online: 0,9 % (July 2000) CLS in 1996 made up 42, with 1289 public libraries. After the administrative and territorial reform introduced in autumn 1996 by the Armenian Parliament, all the public libraries were handed-over to local authorities. The CLS was winded up rapidly, while no new system was established instead. Still there are some regions in the country that continue to operate under the previous centralized system. According to the reform and based on the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia, the territory of the Republic was divided into 10 Marzes. The Yerevan (the capital of the Armenia) got a special administrative status, equal to those of the Marzes. In order to co-ordinate the activities of all libraries throughout the country, Marz Republican Libraries were founded in each Marz. The latter has a direct subordination to the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Youth Affairs. The rest of the Marz libraries are subordinate to the local authorities. There has not been any significant decrease in the number of the libraries during these years. -

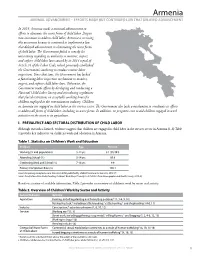

Armenia MINIMAL ADVANCEMENT – EFFORTS MADE but CONTINUED LAW THAT DELAYED ADVANCEMENT

Armenia MINIMAL ADVANCEMENT – EFFORTS MADE BUT CONTINUED LAW THAT DELAYED ADVANCEMENT In 2015, Armenia made a minimal advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. Despite new initiatives to address child labor, Armenia is receiving this assessment because it continued to implement a law that delayed advancement in eliminating the worst forms of child labor. The Government failed to remedy the uncertainty regarding its authority to monitor, inspect, and enforce child labor laws caused by its 2014 repeal of Article 34 of the Labor Code, which previously established the Government’s authority to conduct routine labor inspections. Since that time, the Government has lacked a functioning labor inspection mechanism to monitor, inspect, and enforce child labor laws. Otherwise, the Government made efforts by developing and conducting a National Child Labor Survey and introducing regulations that placed restrictions on acceptable working hours for children employed in the entertainment industry. Children in Armenia are engaged in child labor in the services sector. The Government also lacks a mechanism to coordinate its efforts to address all forms of child labor, including its worst forms. In addition, no programs exist to aid children engaged in work activities on the street or in agriculture. I. PREVALENCE AND SECTORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CHILD LABOR Although research is limited, evidence suggests that children are engaged in child labor in the services sector in Armenia.(1-6) Table 1 provides key indicators on children’s work and education in Armenia. Table 1. Statistics on Children’s Work and Education Children Age Percent Working (% and population) 5-14 yrs.