Why Lizards Need Elephants to Survive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Giant's Comeback

W INT E R 2 0 1 0 n o s d o D y l l i B Home to elephants, rhinos and more, African Heartlands are conservation landscapes large enough to sustain a diversity of species for centuries to come. In these landscapes— places like Kilimanjaro and Samburu—AWF and its partners are pioneering lasting conservation strate- gies that benefit wildlife and people alike. Inside TH I S ISSUE n e s r u a L a n a h S page 4 These giraffes are members of the only viable population of West African giraffe remaining in the wild. A few herds live in a small AWF Goes to West Africa area in Niger outside Regional Parc W. AWF launches the Regional Parc W Heartland. A Giant’s Comeback t looks like a giraffe, walks like a giraffe, eats totaling a scant 190-200 individuals. All live in like a giraffe and is indeed a giraffe. But a small area—dubbed “the Giraffe Zone”— IGiraffa camelopardalis peralta (the scientific outside the W National Parc in Niger, one of name for the West African giraffe) is a distinct the three national parks that lie in AWF’s new page 6 subspecies of mother nature’s tallest mammal, transboundary Heartland in West Africa (see A Quality Brew having split from a common ancestral popula- pp. 4-5). Conserving the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro tion some 35,000 years ago. This genetic Entering the Zone with good coffee. distinction is apparent in its large orange- Located southeast of Niamey, Niger’s brown skin pattern, which is more lightly- capital, the Giraffe Zone spans just a few hun- colored than that of other giraffes. -

22.NE/26 Gebremedhin 421-432*.Indd

Galemys 22 (nº especial): 421-432, 2010 ISSN: 1137-8700 DEMOGRAPHY, DISTRIBUTION AND MANAGEMENT OF WALIA IBEX (Capra walie) BERIHUN GEBREMEDHIN1, GENTILE FRANCESCO FICETOLA2, ØYSTEIN FLAGSTAD3 & PIERRE TABERLET4 1. Animal Genetic Resource Department, Institute of Biodiversity Conservation, PO Box 30726, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. ([email protected]) 2. Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milano, Italy. 3. Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, 7485 Trondheim, Norway. 4. Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine, CNRS UMR 5553, Universit ´e Joseph Fourier, Grenoble, France. ABSTRACT The Walia ibex (Capra walie) is an endemic species representing the genus Capra in Ethiopia. The Simen Mountains National Park(SMNP) is the southern limit of the genus and the only place where the species is found. This review paper will attempt to discuss the conservation status and management problems of the endemic Walia ibex. The size of the population has been increasing slightly since the last one decade. Management system has been improved. However, there is only one single population and the size of the habitat is very small. Human population around the Park and its surroundings is increasing from time to time. Overgrazing and transmission of diseases from domestic livestock and hybridization are serious threats that need especial attention by conservation managers. Key words: critically endangered, Ethiopia, population trend, re-introduction, Simen mountains, suitable habitat. RESUMEN Demografia, distribución y menejo de la población de Capra walie La ibex walie (Capra walie), es una especie endémica de Etiopia y es el representante mas meridional del genero Capra en el mundo, en concreto en el Parque nacional de las Montañas de Simein, único enclave en el que la podemos encontrar. -

The Status and Distribution of Mediterranean Mammals

THE STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF MEDITERRANEAN MAMMALS Compiled by Helen J. Temple and Annabelle Cuttelod AN E AN R R E IT MED The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ – Regional Assessment THE STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION OF MEDITERRANEAN MAMMALS Compiled by Helen J. Temple and Annabelle Cuttelod The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ – Regional Assessment The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or other participating organizations, concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK Copyright: © 2009 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Red List logo: © 2008 Citation: Temple, H.J. and Cuttelod, A. (Compilers). 2009. The Status and Distribution of Mediterranean Mammals. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK : IUCN. vii+32pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1163-8 Cover design: Cambridge Publishers Cover photo: Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus © Antonio Rivas/P. Ex-situ Lince Ibérico All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). -

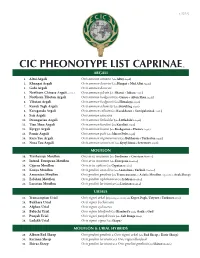

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Site Report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and Adjacent Protected Areas

Site report: Kafa Biosphere Reserve and adjacent Protected Areas Part of the NABU / Zoo Leipzig Project ‘Field research and genetic mapping of large carnivores in Ethiopia’ Hans Bauer, Alemayehu Acha, Siraj Hussein and Claudio Sillero-Zubiri Addis Ababa, May 2016 Contents Implementing institutions and contact persons: .......................................................................................... 3 Preamble ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Objective ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Description of the study site ......................................................................................................................... 5 Kafa Biosphere Reserve ............................................................................................................................ 5 Chebera Churchura NP .............................................................................................................................. 5 Omo NP and the adjacent Tama Reserve and Mago NP .......................................................................... 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ -

Proceedings of the 43Rd Annual National Conference of the American Association of Zoo Keepers, Inc

Proceedings of the 43rd Annual National Conference of the American Association of Zoo Keepers, Inc. September 19th – 23rd Papers Table of Contents Papers Click on the Title to View the Paper Tuesday, September 20th Making a Difference with AAZK’s Bowling for Rhinos Patty Pearthree, AAZK, Inc Bowling for Rhino: The Evolution of Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and Conservation and Development Impact Ruwaydah Abdul-Rahman, Lewa Wildlife Conservancy Indonesian Rhinos: Bowling for Rhinos is Conserving the Most Critically Endangered Mammals on Earth CeCe Sieffert, International Rhino Foundation Action for Cheetas in Kenya: Technology for a National Cheeta Survey Mary Wykstra, Action for Cheetas in Kenya Thursday, September 22nd Reintroduction of orphaned white rhino (Ceratotherium simum simum) calves Matthew Lamoreaux &Clarice Brewer, White Oak Conservation Holdings, LLC Use of fission-fusion to decrease aggression in a family group of western lowland gorillas David Minich and Grace Maloy, Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden Case Study: Medical Management of an Infant Mandrill at the Houston Zoo Ashley Kramer, Houston Zoo, Inc. Coolio, the Elephant Seal in the ‘burgh Amanda Westerlund, Pittsburgh Zoo &PPG Aquarium Goose’s Tale: The Story of how a One-Legged Lemur Gained a Foothold on Life Catlin Kenney, Lemur Conservation Foundation A Syringe Full of Banana Helps the Medicine Go Down: Syringe Training of Captive Giraffe David Bachus, Lion Country Safari Sticking my Neck out for Giraffe, a Keepers journey to Africa to help conserve giraffe Melaina Wallace, Disney’s Animal Kingdom Eavesdropping on Tigers: How Zoos are Building the World’s First Acoustic Monitoring Network for Wild Tiger Populations Courtney Dunn & Emily Ferlemann, The Prusten Project Sending out a Tapir SOS: Connecting guests with conservation John Scaramucci & Mary Fields, Houston Zoo, Inc. -

(Agro Pontino, Central Italy): New Constraints on the Last Interglacial

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The archaeological ensemble from Campoverde (Agro Pontino, central Italy): new constraints on the Last Received: 29 June 2018 Accepted: 14 November 2018 Interglacial sea level markers Published: xx xx xxxx F. Marra1, C. Petronio2, P. Ceruleo3, G. Di Stefano2, F. Florindo1, M. Gatta4,5, M. La Rosa6, M. F. Rolfo4 & L. Salari2 We present a combined geomorphological and biochronological study aimed at providing age constraints to the deposits forming a wide paleo-surface in the coastal area of the Tyrrhenian Sea, south of Anzio promontory (central Italy). We review the faunal assemblage recovered in Campoverde, evidencing the occurrence of the modern fallow deer subspecies Dama dama dama, which in peninsular Italy is not present before MIS 5e, providing a post-quem terminus of 125 ka for the deposit hosting the fossil remains. The geomorphological reconstruction shows that Campoverde is located within the highest of three paleosurfaces progressively declining towards the present coast, at average elevations of 36, 26 and 15 m a.s.l. The two lowest paleosurfaces match the elevation of the previously recognized marine terraces in this area; we defne a new, upper marine terrace corresponding to the 36 m paleosurface, which we name Campoverde complex. Based on the provided evidence of an age as young as MIS 5e for this terrace, we discuss the possibility that previous identifcation of a tectonically stable MIS 5e coastline ranging 10–8 m a.s.l. in this area should be revised, with signifcant implications on assessment of the amplitude of sea-level oscillations during the Last Interglacial in the Mediterranean Sea. -

Habitat Preference of the Endangered Ethiopian Walia Ibex (Capra Walie) in the Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia

Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 38.1 (2015) 1 Habitat preference of the endangered Ethiopian walia ibex (Capra walie) in the Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia D. Ejigu, A. Bekele, L. Powell & J.–M. Lernould Ejigu, D., Bekele, A., Powell, L. & Lernould, J.–M., 2015. Habitat preference of the endangered Ethiopian walia ibex (Capra walie) in the Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 38.1: 1–10, Doi: https://doi.org/10.32800/abc.2015.38.0001 Abstract Habitat preference of the endangered Ethiopian walia ibex (Capra walie) in the Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia.— Walia ibex (Capra walie) is an endangered and endemic species restricted to the Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. Recent expansion of human populations and livestock grazing in the park has prompted concerns that the range and habitats used by walia ibex have changed. We performed observations of walia ibex, conducted pellet counts of walia ibex and livestock, and measured vegetation and classified habitat characteristics at sample points during wet and dry seasons from October 2009 to November 2011. We assessed the effect of habitat characteristics on the presence of pellets of walia ibex, and then used a spatial model to create a predictive map to determine areas of high potential to support walia ibex. Rocky and shrubby habitats were more preferred than herbaceous habitats. Pellet distribution indicated that livestock and walia ibex were not usually found at the same sample point (i.e., 70% of qua- drats with walia pellets were without livestock droppings; 73% of quadrats with livestock droppings did not have walia pellets). -

Accounting for Intraspecific Variation Transforms Our Understanding of Artiodactyl Social Evolution

ACCOUNTING FOR INTRASPECIFIC VARIATION TRANSFORMS OUR UNDERSTANDING OF ARTIODACTYL SOCIAL EVOLUTION By Monica Irene Miles Loren D. Hayes Hope Klug Associate Professor of UC Foundation Associate Professor of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science (Chair) (Committee Member) Timothy Gaudin UC Foundation Professor of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science (Committee Member) ACCOUNTING FOR INTRASPECIFIC VARIATION TRANSFORMS OUR UNDERSTANDING OF ARTIODACTYL SOCIAL EVOLUTION By Monica Irene Miles A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science: Environmental Science The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee December 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 By Monica Irene Miles All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A major goal in the study of mammalian social systems has been to explain evolutionary transitions in social traits. Recent comparative analyses have used phylogenetic reconstructions to determine the evolution of social traits but have omitted intraspecific variation in social organization (IVSO) and mating systems (IVMS). This study was designed to summarize the extent of IVSO and IVMS in Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla, and determine the ancestral social organization and mating system for Artiodactyla. Some 82% of artiodactyls showed IVSO, whereas 31% exhibited IVMS; 80% of perissodactyls had variable social organization and only one species showed IVMS. The ancestral population of Artiodactyla was predicted to have variable social organization (84%), rather than solitary or group-living. A clear ancestral mating system for Artiodactyla, however, could not be resolved. These results show that intraspecific variation is common in artiodactyls and perissodactyls, and suggest a variable ancestral social organization for Artiodactyla. -

The Phylogeny and Taxonomy of Hippopotamidae (Mammalia: Artiodactyla): a Review Based on Morphology and Cladistic Analysis

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2005? 2005 143? 126 Original Article J.-R. BOISSERIEHIPPOPOTAMIDAE PHYLOGENY AND TAXONOMY Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2005, 143, 1–26. With 11 figures The phylogeny and taxonomy of Hippopotamidae (Mammalia: Artiodactyla): a review based on morphology and cladistic analysis JEAN-RENAUD BOISSERIE1,2* 1Laboratoire de Géobiologie, Biochronologie et Paléontologie Humaine, UMR CNRS 6046, Université de Poitiers, 40 avenue du Recteur, Pineau 86022 Cedex, France 2Laboratory for Human Evolutionary Studies, Department of Integrative Biology, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California at Berkeley, 3101 Valley Life Science Building, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160, USA Received August 2003; accepted for publication June 2004 The phylogeny and taxonomy of the whole family Hippopotamidae is in need of reconsideration, the present confu- sion obstructing palaeoecology and palaeobiogeography studies of these Neogene mammals. The revision of the Hip- popotamidae initiated here deals with the last 8 Myr of African and Asian species. The first thorough cladistic analysis of the family is presented here. The outcome of this analysis, including 37 morphological characters coded for 15 extant and fossil taxa, as well as non-coded features of mandibular morphology, was used to reconstruct broad outlines of hippo phylogeny. Distinct lineages within the paraphyletic genus Hexaprotodon are recognized and char- acterized. In order to harmonize taxonomy and phylogeny, two new genera are created. The genus name Choeropsis is re-validated for the extant Liberian hippo. The nomen Hexaprotodon is restricted to the fossil lineage mostly known in Asia, but also including at least one African species. -

And Large Mammals at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve

NABU’s Biodiversity Assessment at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia Medium (esp. Carnivora and Artiodactyla) and large mammals at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve Hans Bauer 318 MEDIUM AND LARGE MAMMALS Highlights ´ 25 species were recorded. ´ The presence of the endangered wild dog (Lycaon pictus) could not be confirmed; it is possible the species is locally extinct. ´ The presence of lion (Panthera leo) was confirmed; this is the flagship species. ´ Larger mammals are not useful as indicators of forest conservation status due to their very low densities. ´ Camera trapping returned very low capture rates, indicating abnormally low mammal density. This should be confirmed and investigated. ´ An additional survey six months later and on behalf of NABU revealed additional mammal species i.e. the leopard (Panthera pardus). 319 NABU’s Biodiversity Assessment at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia 1. Introduction Ethiopia is known for high levels of biodiversity and but Kafa is known for other important species, such endemism, especially in the highland areas. This is as lion and buffalo. also true for mammals, although levels of endemism are higher in most other taxa. Still, endemic larger Several previous expeditions published mammal lists; mammals include species such as the walia ibex, the the most recent is presented below (Yalden 1976, 1980, Ethiopian wolf, the mountain nyala and the gelada. 1984, 1986; Hillman 1993 as summarised in EWNHS None of these are known to occur in the Kafa zone, 2007): Table 1: Checklist of mammals as summarised -

Deer from Late Miocene to Pleistocene of Western Palearctic: Matching Fossil Record and Molecular Phylogeny Data

Zitteliana B 32 (2014) 115 Deer from Late Miocene to Pleistocene of Western Palearctic: matching fossil record and molecular phylogeny data Roman Croitor Zitteliana B 32, 115 – 153 München, 31.12.2014 Institute of Cultural Heritage, Academy of Sciences of Moldova, Bd. Stefan Cel Mare 1, Md-2028, Chisinau, Moldova; Manuscript received 02.06.2014; revision E-mail: [email protected] accepted 11.11.2014 ISSN 1612 - 4138 Abstract This article proposes a brief overview of opinions on cervid systematics and phylogeny, as well as some unresolved taxonomical issues, morphology and systematics of the most important or little known mainland cervid genera and species from Late Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene of Western Eurasia and from Late Pleistocene and Holocene of North Africa. The Late Miocene genera Cervavitus and Pliocervus from Western Eurasia are included in the subfamily Capreolinae. A cervid close to Cervavitus could be a direct forerunner of the modern genus Alces. The matching of results of molecular phylogeny and data from cervid paleontological record revealed the paleozoogeographical context of origin of modern cervid subfamilies. Subfamilies Capreolinae and Cervinae are regarded as two Late Miocene adaptive radiations within the Palearctic zoogeographic province and Eastern part of Oriental province respectively. The modern clade of Eurasian Capreolinae is significantly depleted due to climate shifts that repeatedly changed climate-geographic conditions of Northern Eurasia. The clade of Cervinae that evolved in stable subtropical conditions gave several later radiations (including the latest one with Cervus, Rusa, Panolia, and Hyelaphus) and remains generally intact until present days. During Plio-Pleistocene, cervines repeatedly dispersed in Palearctic part of Eurasia, however many of those lineages have become extinct.