Opportunity For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Public Libraries Directory In

October 2021 Directory Local Touch Global Reach https://directory.sailor.lib.md.us/pdf/ Maryland Public Library Directory Table of Contents Allegany County Library System........................................................................................................................1/105 Anne Arundel County Public Library................................................................................................................5/105 Baltimore County Public Library.....................................................................................................................11/105 Calvert Library...................................................................................................................................................17/105 Caroline County Public Library.......................................................................................................................21/105 Carroll County Public Library.........................................................................................................................23/105 Cecil County Public Library.............................................................................................................................27/105 Charles County Public Library.........................................................................................................................31/105 Dorchester County Public Library...................................................................................................................35/105 Eastern -

Green V. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore's

Green v. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium 1953 Renovation and upper deck construction of Memorial Stadium1 Jordan Vardon J.D. Candidate, May 2011 University of Maryland School of Law Legal History Seminar: Building Baltimore 1 Kneische. Stadium Baltimore. 1953. Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Library Resource Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................3 II. Historical Background: A Brief History of the Location of Memorial Stadium..............................................................................................................6 A. Ednor Gardens.............................................................................................8 B. Venable Park..............................................................................................10 C. Mount Royal Reservoir..............................................................................12 III. Venable Stadium..............................................................................................16 A. Financial History of Venable Stadium.......................................................19 IV. Baseball in Baltimore.......................................................................................24 V. The Case – Not a Temporary Arrangement.....................................................26 -

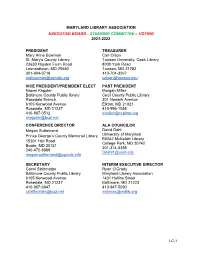

MLA Organizational Structure

MARYLAND LIBRARY ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVE BOARD - STEERING COMMITTEE – VOTING 2021-2022 PRESIDENT TREASURER Mary Anne Bowman Carl Olson St. Mary’s County Library Towson University, Cook Library 23630 Hayden Farm Road 8000 York Road Leonardtown, MD 20650 Towson, MD 21252 301-904-0718 410 - 704 - 3267 [email protected] [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT/PRESIDENT ELECT PAST PRESIDENT Naomi Keppler Morgan Miller Baltimore County Public library Cecil County Public Library Rosedale Branch 301 Newark Avenue 6105 Kenwood Avenue Elkton, MD 21921 Rosedale, MD 21237 410 - 996 - 1055 410-887-0512 [email protected] [email protected] CONFERENCE DIRECTOR ALA COUNCILOR Megan Sutherland David Dahl Prince George’s County Memorial Library University of Maryland B0242 McKeldin Library 15301 Hall Road College Park, MD 20742 Bowie, MD 20721 301-314-0395 240-472-8889 [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Conni Strittmatter Ryan O’Grady Baltimore County Public Library M ary land Library Association 6105 Kenwood Avenue 1401 Hollins Street Rosedale, MD 21237 Baltimore, MD 21223 410-887-6047 410 - 947 - 5090 [email protected] [email protected] I-C-1 EXECUTIVE BOARD – APPOINTED OFFICERS - VOTING 2021-2022 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT LEGISLATIVE Tyler Wolfe Andrea Berstler Baltimore County Public Library Carroll County Public Library 3202 Bayonne Avenue 1100 Green Valley Road Baltimore, MD 21214 New Windsor, MD 21776 410-905-6866 443-293-3136 cell: 443-487-1716 [email protected] [email protected] INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM Andrea -

Market Center Strategic Revitalization Plan Advisory Committee (In Alphabetical Order)

Market Center Strategic Revitalization Plan Advisory Committee (in alphabetical order) The following entities have been invited to participate on the Advisory Committee, but we are open to adding more Advisory Committee members. To serve on the Advisory Committee, you must be willing to commit time to meetings and reviewing documents between meetings. If you are interested in serving on the Advisory Committee, please contact Kristen Mitchell at 443-478-3014. There are also other substantive ways to participate in this planning process, including focus groups, subcommittee meetings on specific subjects, such as housing and transportation, and public meetings. 1. Baltimore Development Corporation, Kyree West 2. Baltimore Heritage, Johns Hopkins 3. Baltimore Leadership School for Young Women (Invited) 4. Behavioral Health System Baltimore, Mark Slater 5. Bromo Arts & Entertainment District 6. Catholic Relief Services, Janee Franklin 7. City Center Residents Association 8. Downtown Partnership of Baltimore 9. Enoch Pratt Free Library (Invited) 10. Greater Baltimore Urban League (Invited) 11. Lexington Market, Inc., Robert Thomas 12. Market Center Community Development Corporation, Wendy Blair 13. Market Center Merchants Association, Judson Kerr 14. University of Maryland, Baltimore, Stuart Sirota 15. University of Maryland Medical Center, Samuel Burris 16. Veterans Administration Hospital, Stephanie O’Connell Resource Team: 1. Baltimore City Department of Planning, Reni Lawal 2. Baltimore City Department of Transportation, Theo Ngongang 3. Maryland Transit Administration, Patrick McMahon 4. Maryland Stadium Authority, Rachelina Bonacci 5. Maryland Department of Planning, Victoria Olivier 6. Maryland Department of Housing & Community Development, Nick Mayr 7. Representative of Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young 8. Representative of Council President Brandon Scott, Scott Davis 9. -

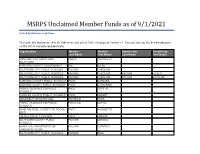

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds As of 4/30/2021

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds as of 9/1/2021 Sorted by Member Last Name To search this document, click the Edit menu and select Find, or just press Control + F. You can also use the Bookmarks pane on the left to navigate alphabetically. Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PABLA TARUNJEET BALTIMORE HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PAC ELLEN BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELISEO BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELIZALDE HARFORD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE BARBARA HOWARD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE CATHERINE PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACE CRYSTAL SCHOOLS CHARLES COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE ROBERT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PACHECO ELVIA PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACHECO MAYRA SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO DEPT OF SOCIAL PACK ANJENETTE SERV TALBOT COUNTY COUNCIL PACK LANARD BALTIMORE COUNTY PUBLIC PACKER AMANDA SCHOOLS MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF PACKER KIMBERLY TRANSPORTATION BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDER IRAM Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK SCHOOLS PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK PADDOCK LANDON SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDY GLADYS PADDY CYNTHIA WESTERN MARYLAND HOSPITAL PADEN GLENNA PADEN HAROLD CENTER PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADEN JENNIFER SCHOOLS WASHINGTON COUNTY PUBLIC PADEN JULIAN PADEN MARY SCHOOLS TOWN OF CHEVERLY PADGETT MATTHEW HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PADGETT TIFFANY -

2020 Annual Report

2020 Maryland State Library Annual Report 25 S. Charles St., Suite 1310 Baltimore, MD 21201 T: 667.219.4800 www.marylandlibraries.org MESSAGE FROM THE STATE LIBRARIAN IRENE PADILLA STATE LIBRARIAN The Maryland State Library (MSL) celebrated our third year as an independent agency. We’ve learned so much and continue to expand the types of services we provide to our customers. We are proud to announce that in fiscal year 2020, MSL: • Distributed over $2.2 million in federal grant awards to support Maryland public libraries, an increase of over 300% since the agency was established in 2017. • Changed the name of the Maryland State Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped to the Maryland State Library for the Blind and Print Disabled (LBPD) and added the requirement that one member of the Maryland State Library Board shall be a blind patron of the LBPD by unanimous approval of the Maryland General Assembly during the 2020 session (SB 326 and HB 604) and passed into law effective October 1, 2020. • Relocated MSL headquarters to 25 South Charles St., Suite 1310, Baltimore, MD 21201. • Provided continuous mail and phone service to blind and low vision customers throughout the pandemic thanks to the commitment of the LBPD staff. • Opened the Maryland Deaf Culture Digital Library website: www.marylanddcdl.org. • Issued the Maryland Day By Day Family Literacy Activity Forever Calendar, including an interactive online version: www.daybydaymd.org. • Sponsored the One Maryland One Book selection What the Eyes Don’t See by Mona Hanna-Attisha. • Hosted the fifth annual MD Tech Connect conference at USM Shady Grove campus, featuring Maryland libraries’ exciting technology projects. -

Request for Proposals: Public Art for Penn-North Metro Station Mezzanine

Public Artwork for Penn-North Metro Station TO BE POSTED: June 6, 2018 Application Deadline: 5:00pm Friday July 6, 2018 Request for Proposals: Public Art for Penn-North Metro Station Mezzanine Budget: $60,000.00 Deadline for Application: 5:00 pm, Friday, July 6, 2018 Apply online at this LINK. The Maryland Department of Transportation Maryland Transit Administration (MDOT MTA) has partnered with the Baltimore Office of Promotion & The Arts (BOPA) to commission a new piece of public artwork for the interior of the Penn-North Metro station. The addition of new artwork is a part of the planned station improvements funded and made possible by North Avenue Rising, a $27.3 million project funded by the US Department of Transportation, Baltimore City Department of Transportation (BCDOT), and the Maryland Department of Transportation. The selected artist will work with the project administrators at BOPA, the North Avenue Rising team from MDOT MTA, as well as various community stakeholders to design and fabricate a permanent public artwork to be featured within the interior of the Metro station. Installation of the artwork will be conducted by MDOT MTA, with participation by the artist. The final artwork should reflect and honor the culture of the community in the area and serve as a positive contribution to the aesthetic experience of commuting through the Penn-North station. Apply Online by 5:00pm July 6, 2018 Public Artwork for Penn-North Metro Station TO BE POSTED: June 6, 2018 Application Deadline: 5:00pm Friday July 6, 2018 The general public will be invited to participate in the process through public meetings, such as public information meetings, and public artist presentation, and by contributing materials, either written (stories, anecdotes, poetry, family names, etc.) or visual (drawings, found images, old photographs etc..) to a “cultural scrapbook” that will be provided to the artist as an inspirational reference, and kept on file as part of the project. -

The Walters Art Museum Year in Review July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014

THE Walters ArT MUSEUM YEAR IN REVIEW JULY 1, 2013–June 30, 2014 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE 50 Walters Women's Committee EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 5 50th Anniversary Gift Donors 52 Recognition Gifts DEPUTY DIRECTORS' REPORTS 7 53 Endowment Gifts and Pledges 54 Named Endowment Funds EXHIBITIONS 13 13 Special Exhibitions VOLUNTEERS 57 14 Focus Exhibitions 57 Corporate Task Force 15 Off-Site Exhibitions 57 Planned Giving Advisory Council 16 Lenders to Walters Exhibitions 57 Walters Enthusiasts Steering Committee 16 Walters Loans to Exhibitions 57 William T. Walters Association 58 The Women's Committee ACQUISITIONS 19 59 Docents 19 Bequests 60 Interns 19 Gifts 60 Volunteers 23 Museum Purchases STAFF 63 STAFF RESEARCH 25 63 Executive Director's Office 25 Publications 63 Art and Program 26 Staff Research and 64 Museum Advancement Professional Activities 64 Administration and Operations DONORS 33 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 67 33 Government 33 Individual and Foundation Donors FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 69 43 Legacy Society 44 Gifts to the Annual Giving Campaign 46 Corporate Supporters 46 Matching Gift Partners 46 Special Project Support 47 Gala 2013 49 Gala 2013 Party 50 Art Blooms 2014 THE Walters ArT MUSEUM: YEAR IN REVIEW 2013–2014 3 Letter froM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR This annual report represents the first full year of my than 69,000 students in the museum, to the increase tenure as the Executive Director of this great Museum. in numbers of objects available to global audiences on What an incredible privilege it has been to be among our Works of Art website. you, a community of people who care deeply about In this report you will notice the reorganization the Walters and who ardently believe that art muse- that I undertook in April 2014 in order to create cross- ums have a role in transforming society. -

Brooklyn Park Youth Athletic Assiciation

2018 2018 Board of Directors Susan Scotto Dyckman Jason Bell Timothy M. Hurley Consultant Bell Wealth Nelson Mullins ToolBank President Management Group Riley & Scarborough, ToolBank Staff LLP Dennis Sanschagrin Jeff Braun Noah Smock Structural Group Stanley Black & Decker Abby Jackson Executive Director ToolBank Vice President Johns Hopkins William J. Brown Carey School of Business John Robinson Exelon/ BGE MB Business Credit Barbara Klein Harper ToolBank Treasurer Jeremy Carpenter UPS Information Services Len the Plumber Ashley Van Stone Brian Pham Rachel Thompson Trash Free Maryland Aandria M.E. Carr Break A Difference ToolBank Secretary Consultant Program Manager Matthew Robinson Greg Ferraro Laureate Education Jones Lang LaSalle Vik Subramaniam Steve Galliard Grant Thornton, LLP The Home Depot Flash QA Supervisor Dear Friends, 2018 was a powerful year for the Baltimore Community ToolBank in service to our partners across a diversity of impact areas. As a regional resource, we fueled projects taking place with our blue tools in Baltimore City, Washington, D.C., throughout the state of Mary- land and even in Pennsylvania and New York City! As simple as it is to share tools, equipment and expertise, we know that when we do so we empower our partners to save time and money for their projects. Our service touches change-agents who work to combat some of the most entrenched issues facing our com- munities. Whether it’s a drill in the hand of a volunteer helping build a new achool playground or our tables and chairs being used for a community picnic, we are proud to support positive work of all shapes and sizes across a wide spectrum. -

Social Workers at the Pratt Make a Meaningful Difference

Summer/Fall 2018 VOL. 19 for donors and friends of the library FROM HEIDI DANIEL On Being Nice Social Workers at This summer, the Enoch Pratt Free the Pratt Make a Library was named one of the Nicest Places in America by Reader’s Digest and Good Morning America. Meaningful Difference HILE THE ARCHITECTURAL detailsf o our Central Librarye ar spectacular, in this case the word “nice” runs deeper. Recently, a customer posted on social mediat tha the Pratt Library opened more doors for her than her degree from Harvard. WThis year, the Library is opening even more doors by going fine-free on all Pratt-owned materials. We’re breaking down barriers for customers who may not be able to afford the cost of overdue fines. The Pratt is leading the way for other libraries in this initiative, becoming the first major urban public library system on the East Coast to go fine-free. In the short time the policy has been in effect, we’ve seene mor people and more materials coming back to the Pratt Social Worker in the Library library. team with UMD partners. HEIDI DANIEL PRESIDENT AND People turn to the Pratt for CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER many different reasons. It is a placee wher someone having issues with housing This spring marked the conclusion of our pilot year of or food insecurity can find a social worker. In its first year, our Social Worker in the Library program Social Worker in the Library, and what a year it was! helped hundreds of library customers. More than 14,000 people have received job search and resume ERVING OVER 600 CUSTOMERS at four social service agencies: 42% related to economic crisis; help from our Mobile Job Center, which has been in Pratt Library branch locations, the high demand since it hit the road in May 2017. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1996, Volume 91, Issue No. 2

A15A Sc 5^/-i- Summer 1996 MARYLAND Historical Magazine T* -'« TC sSe^M • rm *"•.* '. THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY Founded 1844 Dennis A. Fiori, Director The Maryland Historical Magazine Ernest L. Scott Jr., Editor Robert I. Cottom Jr., Associate Editor Patricia Dockman Anderson, Associate Editor Jessica M. Pigza, Managing Editor Jeff Goldman, Photographer Angela Anthony, Robin Donaldson Coblentz, Christopher T.George, Jane Gushing Lange, and Robert W. Schoeberlein, Editorial Associates Regional Editors John B. Wiseman, Frostburg State University Jane G. Sween, Montgomery Gounty Historical Society Pegram Johnson III, Accoceek, Maryland Acting as an editorial board, the Publications Committee of the Maryland Historical Society oversees and supports the magazine staff. Members of the committee are: John W. Mitchell, Upper Marlboro; Trustee/Chair Jean H. Baker, Goucher Gollege James H. Bready, Baltimore Sun Robert J. Brugger, The Johns Hopkins University Press Lois Green Garr, St. Mary's Gity Commission Toby L. Ditz, The Johns Hopkins University Dennis A. Fiori, Maryland Historical Society, ex-officio David G. Fogle, University of Maryland Jack G. Goellner, Baltimore Averil Kadis, Enoch Pratt Free Library Roland G. McGonnell, Morgan State University Norvell E. Miller III, Baltimore Richard Striner, Washington Gollege John G. Van Osdell, Towson State University Alan R. Walden, WBAL, Baltimore Brian Weese, Bibelot, Inc., Pikesville Members Emeritus John Higham, The Johns Hopkins University Samuel Hopkins, Baltimore Gharles McG. Mathias, Chevy Chase The views and conclusions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors. The editors are responsible for the decision to make them public. ISSN 0025-4258 © 1996 by the Maryland Historical Society. Published as a benefit of membership in the Maryland Historical Society in March, June, September, and December. -

Photographs and Ephemera MS 15.4 Finding Aid Prepared by Joan M

Enoch Pratt Free Library: Photographs and Ephemera MS 15.4 Finding aid prepared by Joan M. Wolk This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit December 21, 2016 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Enoch Pratt Free Library Special Collections http://www.prattlibrary.org/ 400 Cathedral Street Baltimore, MD, 21201 443-984-2451 [email protected] Enoch Pratt Free Library: Photographs and Ephemera MS 15.4 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Series I: First Enoch Pratt Free Central Library