Contents More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

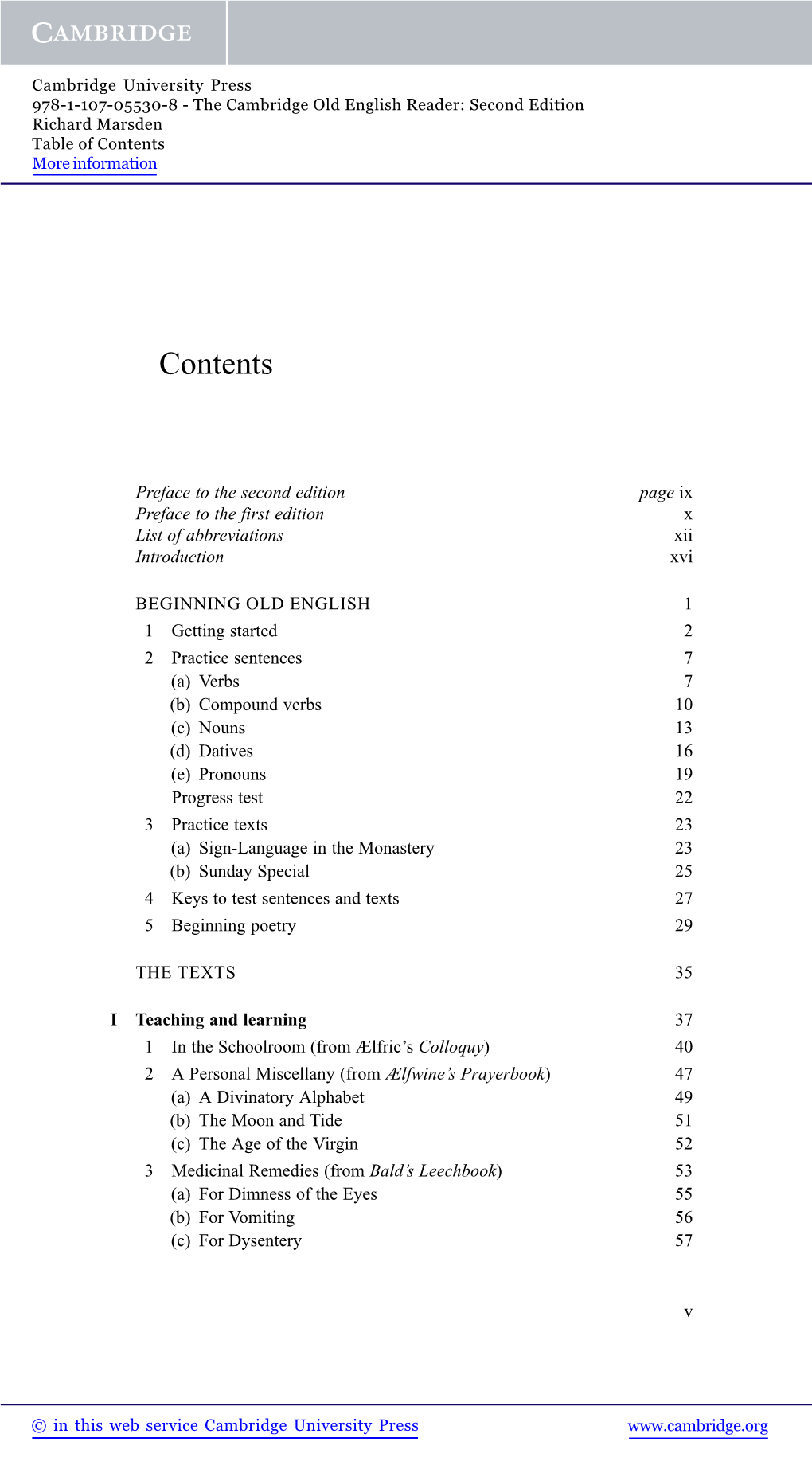

The Cambridge Old English Reader

The Cambridge Old English Reader RICHARD MARSDEN School of English Studies University of Nottingham published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org c Cambridge University Press 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times 10/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Marsden, Richard. The Cambridge Old English reader / Richard Marsden. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0 521 45426 3 (hardback) – ISBN 0 521 45612 6 (paperback) 1. English language – Old English, ca. 450–1100 – Readers. 2. Anglo-Saxons – Literary collections. 3. Anglo-Saxons – Sources. I. Title. PE137.M46 2003 429.86421–dc21 2003043579 ISBN 0 521 45426 3 hardback ISBN 0 521 45612 6 paperback Contents Preface page ix List of abbreviations xi Introduction xv The writing and pronunciation -

Medieval Medievalisms in the Old English Ruin

• Via Rome: Medieval Medievalisms in the Old English Ruin Rory G. Critten University of Lausanne Lausanne, Switzerland The recent publication of The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism under the editorship of Louise D’Arcens marks a crowning moment in the history of a discipline whose institutional backing has not always been so strong.1 For some time now, medievalism studies have been enjoying increasing respect for the insights that they can offer into matters ranging from periodization, colonization, and nationalism, to the potentially mutual imbrication of good scholarship and good fun.2 Since the majority of the contributors to the new Cambridge Companion work both in what we might call traditional medieval studies as well as in medievalism studies, the volume also serves as evidence for the rapprochement between these two fields. A significant facilitating factor in this regard has been a willingness shared across the disciplines to conceive of time not solely in linear terms. Researchers in both camps have met over the recognition that the present, in Carolyn Dinshaw’s words, “is not a singular, fleeting moment but comprises relations to other times, other people, other worlds.”3 Viewed from this perspective, the procedures of both medieval and medievalist texts can be seen to correspond, and the distinc- tion between what is medieval and what comes afterwards is blurred. These intertwining ideas have a rich history of their own. Even in their earliest iterations, medievalism studies highlighted the extent to which paying attention -

Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Literary Anglo-Saxon

ENVIRONMENTAL HUMANITIES IN PRE-MODERN CULTURES Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Heide Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Environmental Humanities in Pre‑modern Cultures This series in environmental humanities offers approaches to medieval, early modern, and global pre-industrial cultures from interdisciplinary environmental perspectives. We invite submissions (both monographs and edited collections) in the fields of ecocriticism, specifically ecofeminism and new ecocritical analyses of under-represented literatures; queer ecologies; posthumanism; waste studies; environmental history; environmental archaeology; animal studies and zooarchaeology; landscape studies; ‘blue humanities’, and studies of environmental/natural disasters and change and their effects on pre-modern cultures. Series Editor Heide Estes, University of Cambridge and Monmouth University Editorial Board Steven Mentz, St. John’s University Gillian Overing, Wake Forest University Philip Slavin, University of Kent Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Heide Estes Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: © Douglas Morse Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 944 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 838 7 doi 10.5117/9789089649447 nur 617 | 684 | 940 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The author / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Treebeard's List – Maxims II

Pre-print extract from S. Lee and E. Solopova, The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature through the fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien (Palgrave, 2005). To purchase full book go to: http://www.palgrave.com/products/title.aspx?PID=27039 0. 4.9 Treebeard’s List – Maxims II (TT, ‘Treebeard’) 4.9.1 Plot Summary Merry and Pippin, having escaped the Orcs, flee into Fangorn’s forest, where they encounter Treebeard, the Ent. Treebeard is puzzled as to what the two Hobbits are and recites an ancient poem which lists the various flora and fauna of Middle-earth. Christopher Tolkien (Treason, pp. 411-21) notes that the character of Treebeard, and the Ents themselves, seem to have come late to Tolkien, and he puzzled over how they would fit into the story. 4.9.2 Medieval Text: Maxims II Maxims II is found in a British Library manuscript – Cotton MS Tiberius B.i (ff. 115r-v). It’s dating is troublesome, and the nature of the poem suggests ancient folklore passed down from generation to generation (as indeed Treebeard’s poem was). Cassidy and Ringler argue that it ‘probably reached its present form in the tenth century or slightly earlier, though some of the material in it may be much older’ (1974, p. 373). It is called Maxims II because a very similar poem (Maxims I) appears in ‘The Exeter Book’. A ‘Maxim’, according to the OED is: ‘A rule or principle of conduct. Also: a pithily expressed precept of morality or prudence (spec. occurring in Old English verse); such a precept as a literary form.’ Marsden (2004, p. -

Intertextuality of Deor

Vol. 4(8), pp. 132-138, October, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/JLC11.080 Journal of Languages and Culture ISSN 2141-6540 © 2013 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/JLC Review Intertextuality of Deor Raimondo Murgia Tallinn University, Narva mnt 25, 10120 Tallinn, Estonia. Accepted 22 November, 2012 The Deor is a poem found in the Exeter Book and included in the Old English elegies. The main purpose of this contribution is to highlight the possible intertextual links of the poem. After an outline of the old English elegies and a brief review of the most significant passages from the elegies, this short poem will be analyzed stanza by stanza. An attempt will be made to demonstrate that the various interpretations of the text depend on particular keywords that require that the readers to share the same time and space coordinates as the author. The personal names are the most important clues for interpretation. The problem is that they have been emended differently according to the editors and that the reader is supposed to know the referent hinted by those particular names. Key words: Old English elegies, Exeter Book, Deor, intertextuality. INTRODUCTION OF THE OLD ENGLISH ELEGIES It must be underlined that the term „elegy‟ applying to old definition of Old English elegy is Greenfield‟s (1965): “a English (hereafter OE) poetry could be misleading since relatively short reflective or dramatic poem embodying a one would expect the meter of such poetry to be the contrastive pattern of loss and consolation, ostensibly same as the Greek and Latin Elegies, in which their based upon a specific personal experience or observa- elegiac distich (Pinotti, 2002) points out that in the fourth tion, and expressing an attitude towards that experience”. -

Abstract Old English Elegies: Language and Genre

ABSTRACT OLD ENGLISH ELEGIES: LANGUAGE AND GENRE Stephanie Opfer, PhD Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2017 Dr. Susan E. Deskis, Director The Old English elegies include a group of poems found in the Exeter Book manuscript that have traditionally been treated as a single genre due to their general sense of lament – The Wanderer, The Seafarer, The Riming Poem, Deor, Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wife’s Lament, Resignation, Riddle 60, The Husband’s Message, and The Ruin. In this study, I conduct a linguistic stylistic analysis of all ten poems using systemic functional linguistics (SFL) and a variety of computational and linguistic tools: Lexomics, Voyant, and Microsoft Excel. My results focus on three characteristics of the poetry: (1) the similarity of the linguistic style within the poems, measured by Lexomics; (2) an oscillation between first- and third-person clausal Themes, measured using SFL analysis; and (3) themes in the lexical categorization, measured through detailed lexical analysis. In the end, my methodology creates a new and more nuanced definition of the elegy: a relatively short reflective or dramatic poem, similar in style and content to other elegiac poems, that alternates between first- and third-person perspectives and includes (1) themes of exile; (2) imagery of water or the sea, the earth, and/or the weather; and (3) words expressing both joy and sorrow. Ultimately, I argue for a recategorization of only five poems as “Old English elegies”: The Wanderer, The Seafarer, Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wife’s Lament, and The Riming Poem. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2017 OLD ENGLISH ELEGIES: LANGUAGE AND GENRE BY STEPHANIE OPFER ©2017 Stephanie Opfer A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Doctoral Director: Dr. -

Selim 19.Indb

EORÐSCRÆF, EGLOND AND ISCEALDNE SÆ: LANDSCAPE, LITERALISM AND METAPHOR IN SOME OLD ENGLISH ELEGIES Abstract: This article explores the depictions of landscape in the Old English elegies The Wife’s Lament, Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wanderer and The Seafarer. For many years scholars have debated how to interpret these depictions and have been deeply divided over whether landscape is to be understood literally or metaphorically in Old English poetry. This article reassesses these poems to argue for a more complex interaction between the literal and fi gurative aspects of landscape setting than has thus far been appreciated. Keywords: landscape, Old English poetry, The Wife’s Lament, Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wanderer, The Seafarer, isolation. Resumen: Este artículo explora las descripciones paisajísticas en las elegías anglosajonas The Wife’s Lament, Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wanderer y The Seafarer. Durante muchos años los estudiosos han debatido cómo interpretar estas descripciones y se han dividido acerca de si en la poesía anglosajona el paisaje debe entenderse literal o metafóricamente. Este artículo reconsidera estos poemas y defi ende una interacción más compleja entre los aspectos literales y fi gurativos de escenario paisajístico de lo que se ha hecho hasta ahora. Palabras clave: paisaje, poesía anglosajona, The Wife’s Lament, Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wanderer, The Seafarer, aislamiento. 1 Introduction – Literal and Metaphorical Landscapes andscape settings in Old English poetry have been a subject of heated debate throughout the twentieth Lcentury, -

Old English Literature: a Brief Summary

Volume II, Issue II, June 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Old English Literature: A Brief Summary Nasib Kumari Student J.k. Memorial College of Education Barsana Mor Birhi Kalan Charkhi Dadri Introduction Old English literature (sometimes referred to as Anglo-Saxon literature) encompasses literature written in Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon) in Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066. "Cædmon's Hymn", composed in the 7th century according to Bede, is often considered the oldest extant poem in English, whereas the later poem, The Grave is one of the final poems written in Old English, and presents a transitional text between Old and Middle English.[1] Likewise, the Peterborough Chronicle continues until the 12th century. The poem Beowulf, which often begins the traditional canon of English literature, is the most famous work of Old English literature. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has also proven significant for historical study, preserving a chronology of early English history.Alexander Souter names the commentary on Paul's epistles by Pelagius "the earliest extant work by a British author".[2][3] In descending order of quantity, Old English literature consists of: sermons and saints' lives, biblical translations; translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers; Anglo-Saxon chronicles and narrative history works; laws, wills and other legal works; practical works ongrammar, medicine, geography; and poetry.[4] In all there are over 400 survivingmanuscripts from the period, of which about 189 are considered "major".[5] Besides Old English literature, Anglo-Saxons wrote a number of Anglo-Latin works. -

The Legacy and Long Afterlife of Old English Poetry

Robert E. Bjork In recent years the most celebrated and Arts & Humanities︱ successful re-telling of the story has been by the Irish poet Seamus Heaney. Other poets have imagined the tale from a different perspective; for example the English writer Maureen Duffy has written a poem from the dragon’s point The legacy and of view. For Dr Bjork, one of the most imaginative re-tellings has been by the American author Michael Crichton, whose novel ‘Eaters of the Dead’ was in turn the source for the film ‘The Thirteenth Warrior’ starring Antonio long afterlife of Banderas. Perhaps the greatest testament to the universal, psychological appeal of Beowulf’s good versus evil narrative Old English poetry is its re-imagining in different media Left: First page of ‘Beowulf’, which have handed the story to a new contained in the damaged Nowell The Germanic people who or a body of literature recorded in Carta, Bayeux Tapestry, Book of Kells Codex. Right: Remounted page global generation. This includes comic inhabited England before just four manuscripts, Old English and the Diary of Anne Frank. from ‘Beowulf’, British Library strips, graphic novels, video games, Cotton Vitellius A.XV. William the Conqueror became Fpoetry has a legacy that belies board games, art and music, from choral ruler in 1066 spoke a language the small number of works that have Small wonder then, that the afterlife works to operas and contemporary known as Old English. Steeped survived the 1,000 or more years since of Old English poetry is long, despite named ‘Beowulf’ in the rock. -

J.R.R. Tolkien's Use of an Old English Charm

J.R.R. Tolkien's use of an Old English charm Edward Pettit .R.R. Tolkien wanted to create - or, as he saw it, rediscover - a A smith sat, forged a little knife (seax), mythology for England, its native heathen tales having been Badly wounded by iron. Jalmost entirely lost due to the country's relatively early Out, little spear, if you are in here! conversion to Christianity and the cultural and linguistic Six smiths sat, made war-spears. transformation initiated by the Norman Conquest.1-2 Apart from Out, spear! Not in spear! the English treatment of the Scandinavian pagan past in the Old If a piece of iron (isenes dcel) is in here. English poem Beowulf, scraps of lore in other Anglo-Saxon heroic The work of a witch (liceglessan), heat shall melt (gemyllan) it! poems, chronicles and Latin histories; 'impoverished chap-book If you were shot in the skin, or were shot in the flesh, stuff from centuries later;3 and inferences Tolkien could make using Or were shot in the blood. his philological expertise and knowledge of Old Norse literature, he Or were shot in the limb, never may your life be injured. had little other than his imagination to go on - barely more than the If it were shot of gods (esa), or if it were shot of elves (ylfa), names of a few gods, mythical creatures and heroic ancestors.4 Or if it were shot of witch (hxglessan), now I will help you. However, a few Anglo-Saxon charms do provide tantalising This is your cure for shot of gods, this is your cure for shot of glimpses of something more. -

Corene Cneoris

Corene Cneoris A Late-Period Anglo-Saxon Riddle in Alliterative Verse from England written in Old and Modern English Bird-shaped shield mount from the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, early 7th Century, British Museum 1939,1010.94.C.1 Lady Elenor de La Rochelle alias Ela The Shire of Roxbury Mill Poeta Atlantiae Ruby Joust, Barony of Caer Mear A.S. LIV Calligraphed display by Lady Kaaren Valravn 1 Contents Original Poem: “Corene Cneoris” .................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 The Form of Anglo-Saxon Alliterative Verse ................................................................................ 4 Exemplars and Inspiration .............................................................................................................. 7 Exemplar 1: Riddle 8 (or 6) from the Exeter Book .................................................................... 7 Exemplar 2: Wulf and Eadwacer ................................................................................................ 9 Analysis of the Original Poem ...................................................................................................... 12 Composition Process ................................................................................................................. 12 Poetic Structure, Orthography, and Format ............................................................................. -

Unit I, Module II, P 1 MODULE II Features of Anglo-Saxon Poetry

MODULE II ELEGIAC POETRY In this module you are going to learn: Features of Anglo-Saxon lyrical poetry with special reference to Widsith and Deor’s Lament Introduction to elegiac poetry Instances of elegiac poetry: The Seafarer, The Wanderer, The Wife’s Lament, The Husband’s Message, The Ruin and, Wulf and Eadwacer. Features of Anglo-Saxon Poetry You have already learnt a few aspects of the Anglo-Saxon society. You must have realised the importance of literature in their culture. The verse form that is used in the Anglo-Saxon poetry originates in the continent. It was brought along by the migrating tribes of the fifth century. This poetry was oral in nature and was sung in the courts of the kings or the mead halls as shown in the heroic literature. Primarily, these stories served the purpose of history as they told the stories of great German heroes, local kings; later after Christianization, Biblical stories were also added to the repertoire. However, as time passed by, the clerics began to keep a written record of the poems. This preserved the pagan songs but in many ways compromised their tone as the Christian philosophy was interpolated. Earliest instances of writing, which was related to Christian theology, could be found around eighth century. Remember, the clerics who wrote were the descendents of heroic society, thus the Christian verses would have images and words that are associated with their heroic past. The Anglo-Saxon literature or Old English literature (many scholars prefer the term ‘Old English’ because the society was not just composed of Angles or Saxons but a number of other races) thus is an odd mixture of both pagan and Christian wisdom.