THE STORYTELLER Saki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

CLASS : 2 SUBJECT : EVS TOPIC : MY FAMILY Family : a Family Is A

CLASS : 2 SUBJECT : EVS TOPIC : MY FAMILY Family : A family is a group of people who are related to each other . Members of a family : Father Mother Children Grand father Grand mother Uncle Aunt Cousins etc…. Relationship : Father’s father - Grand father Father’s mother - Grand mother Mother’s father - Grand father Mother’s mother - Grand mother Father’s /mother’s brother - Uncle Father’s / Mother’s sister - Aunt Cousins - Uncle’s / Aunt’s children Niece - Daughter of one’s brother /sister Nephew - Son of one’s brother / sister Types of family : 1 . Small family ( Nuclear family ) : * A family with parents and one or two children is called small family. * Child lives with his father, mother and a brother/ sister. This is a small family. * Small family is a happy family . * Small family is also known as nuclear family. 2. Big family : * A family with parents and more than two children is called large family * Child lives with his father, mother, sisters and brothers. 3. Joint family : * Child lives with his mother, father, brother, grandmother, grandfather, uncle, aunt and cousins is called joint family . Importance of family : We get everything from the family . Our parents gives us food, toys, send us to school and take great care of us. We must listen to our parents and elders. We can help them by doing work like dusting, watering plants taking care of grandparents. Match the following : 1 . Grand father - father’s brother 2. Cousins - mother’s father 3. Uncle - uncle’s and aunt’s children 4. Grand mother - mother’s sister 5. -

My Aunt's Mamilla

My father’s eldest sister has always served in My Aunt’s Mamilla my mind as a potential family encyclopedia. Helga Tawil-Souri “Potential” because I never had the opportunity to spend much time with her. She had come and visited us in Beirut once in the mid 1970s – I vaguely remember. My grandmother, with whom I spent much of my childhood, would often mention Auntie M. under a nostalgic haze, perhaps regret, that her first-born was so far away. That longing tone for her eldest led my other aunts, my father, and my uncles to joke that Auntie M. was their mother’s favorite. For years Auntie M. endured only in my imagination. Whatever tidbits I had caught about her were extraordinary, a fusion of new world mystery and old world obscurity. She lived in faraway places that sounded utterly exotic: Sao Paolo, Etobicoke, Toronto; that they always rhymed only added to their enigma. The haphazard trail I constructed of her life seemed improbable too: old enough to remember family life in Jerusalem; married and sent off to Brazil; had a daughter ten years older than me who didn’t speak Arabic. Auntie M. hovered behind a veil of unanswered questions: How old was she? Did my grandparents marry her off or did she choose to wed Uncle A.? How is one “sent” to Brazil? Could one even fly to Brazil back then? Did she flee with the family to Lebanon first? Did she really have another daughter besides the one I knew of? What happened to the other daughter? How did Auntie M. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Aunt Lee's Chicken Eggs

Name: _________________________________ Aunt Lee’s Chicken Eggs By Susan Manzke Some people have cats or dogs as pets. Aunt Lee is not like those people. Her two pets are chickens. Both are girl birds, or hens. One is named Lulu and the other is Molly. Cindy came to visit Aunt Lee to help with her pets. “It is time to collect eggs,” said Aunt Lee. She handed her niece a basket. Molly and Lulu were looking for bugs in the backyard when Cindy went to the chicken house. There was one egg in the nest. Cindy took it and put it in her basket. As she walked toward the house, Cindy saw something white under a bush. It was another egg. She picked it up and put it in her basket, too. “Two eggs, Aunt Lee,” said Cindy. “I found one in a nest and the other one under a bush.” “Oh my,” said Aunt Lee. “I hope the one from under the bush is good. If it was there for a long time, maybe it is old. It could make us sick. Which egg was under the bush?” Cindy looked into the basket. The eggs looked the same. “I don’t know,” she said. “Don’t worry,” said Aunt Lee. “I have a trick to figure out if an egg is good or not.” She ran water into a bucket. “Gently put both eggs into the water, Cindy. A good egg will sink to the bottom. A bad egg will float.” Cindy put the eggs in the water. Both eggs went to the bottom. -

BBC Learning English Quiznet Family

BBC Learning English Quiznet Family Quiz Topic: Family 1. When we were younger, my brother and I didn't really ______________, but now we have a good relationship. a) get on b) get off c) get away d) get to 2. My brother has 2 children; the boy is my nephew and the girl is my ________________. a) cousin b) niece c) sister d) aunt 3. My grandmother's mother is my _____________-grandmother; (there are 4 generations) a) grand b) great c) high d) big 4. Your siblings are your ____________! a) parents b) brothers and sisters c) cousins d) friends 5. I got divorced some years ago, but I still speak to my _______________. a) old wife b) before wife c) ex-wife d) previous 6. Uncles, aunts, cousins, nieces and nephews are all relatives and are sometimes known as a part of our _____________ family. a) nuclear b) outside c) distant d) extended Quiznet © BBC Learning English Page 1 of 3 bbclearningenglish.com ANSWERS Quiz Topic: Family 1. When we were younger, my brother and I didn't really ______________, but now we have a good relationship. a) get on b) get off c) get away d) get to a) If you have a good relationship, you can say you get on (well together). b) Which multi-word verb is used to describe a relationship that's either good or difficult? c) Which multi-word verb is used to describe a relationship that's either good or difficult? d) Which multi-word verb is used to describe a relationship that's either good or difficult? 2. -

Ontario Employment Standards Act – Leaves of Absence (“Loa”) – March 2020

ONTARIO EMPLOYMENT STANDARDS ACT – LEAVES OF ABSENCE (“LOA”) – MARCH 2020 GENERAL LOA available to employees whether fulltime, part-time, permanent or temporary SICK/FAMILY Length of UNPAID Leave: RESPONSIBILITY/BEREAVEMENT • 3 days Sick Leave LEAVE • 3 days Family Responsibility Leave • 2 days Bereavement Leave Eligibility: Available after 2 weeks of employment Criteria: Leave must be taken for: a. Sick leave - Personal illness, injury or medical emergency b. Family Responsibility Leave • Illness, injury or medical emergency of a family member • An urgent matter that concerns a family member c. Bereavement Leave – death of a family member Family Member: • The employee’s spouse. • A parent, step-parent or foster parent of the employee or the employee’s spouse. • A child, step-child or foster child of the employee or the employee’s spouse. • A grandparent, step-grandparent, grandchild or step- grandchild of the employee or of the employee’s spouse. • The spouse of a child of the employee. • The employee’s brother or sister. • A relative of the employee who is dependent on the employee for care or assistance Notice: Employee must advise employer he/she is taking the leave before or as soon after taking the leave as possible. Time Away from Work: Any part of a day will be counted as a full day’s leave – This is optional. An employer can provide employees with a better benefit, i.e., count half days. Evidence: An employer may require an employee who takes a PEL day to provide evidence “reasonable in the circumstances” that the employee is entitled to the leave. -

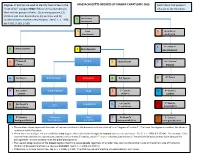

MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES of KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each Title Is That Person’S “Next of Kin” Category ONLY If There Are No Members in Relation to the Decedent

Degrees of kinship are used to identify heirs at law in the MASSACHUSETTS DEGREES OF KINSHIP CHART (MPC 960) Each title is that person’s “next of kin” category ONLY if there are no members in relation to the Decedent. the first four groups of heirs: (1) surviving spouse, (2) children and their descendants, (3) parents, and (4) brothers/sisters and their descendants. See G. L. c. 190B, 4 Great-Great Grandparent §§ 2-102, 2-103, 2-106. 3 Great 5 Great-Great Grandparent Aunt/Uncle 6 1st Cousin of 4 Great Aunt/Uncle 2 Grandparent Grandparent 5 1st Cousin of Parent 3 Aunt/Uncle 7 2nd Cousin of Parent Parent rd 6 2nd Cousin Brother/Sister Decedent 4 1st Cousin 8 3 Cousin 7 2nd Cousin’s Niece/Nephew Child 5 1st Cousin’s 9 3rd Cousin’s Children Children Children 1st Cousin’s 10 3rd Cousin’s 8 2nd Cousin’s Great Grandchild 6 Grandchildren Grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchildren 9 2nd Cousin’s Great-great Great 7 1st Cousin’s 11 3rd Cousin’s Great-grandchildren Niece/Nephew Grandchild Great-grandchildren Great-grandchildren The numbers above represent the order of nearness in blood to the deceased and are referred to as “degrees of kindred”. The lower the degree or number, the closer a relation is to the Decedent. When there are multiple relations with the same degree, those who claim through the nearest ancestor are preferred. See G. L. c. 190B, § 2-103 (4). For example, if the nearest living relatives are a great-aunt, a great-uncle and two 1st cousins, all are 4th degree relations, but the two 1st cousins inherit because they claim through the grandparents - a closer ancestor than the great-grandparents. -

Happy Mother's Day, Grandma! Little Did We Realize When We Visited My

Happy Mother ’s Day, Grandma! Page 1 of 3 Happy Mother ’s Day, Grandma! Little did we realize when we visited my Aunt Ruby last week in North Little Rock, Arkansas that it was going to be the last opportunity this side of Heaven to see her. My mom has been missing her and although she was under the weather herself, she had this very strong urge to have us drop her off to spend the week with her precious sister. My mom called at 4:30 Thursday morning just before I left for the National Day of Prayer meeting here at Christchurch to inform me of the passing of Aunt Ruby. All day long memories of our very special aunt have been flooding my mind. Aunt Ruby was academically challenged, physically challenged and had a severe impediment of speech. My grandfather and grandmother tried sending her to more than one school, but every time the teachers sent her back home saying they were unable to teach her. My loving grandparents were heartbroken as other children would make fun of her. The final straw that broke the attempts to formally educate her came when her frail body could not sustain the see-saw ride and she fell, breaking her fragile little arm. She never saw the end of her second grade…and that’s about how we knew her for the rest of our lives, locked- in at grade two. But at home, she found a haven of love and comfort. Recently, I was looking at pictures of my mom, Aunt Florene, Aunt Pearlene and Aunt Ruby when they were little girls in the Great Depression. -

Aunt Kipp Louisa May Alcott

AUNT KIPP LOUISA MAY ALCOTT "Children and fools speak the truth." "What's that sigh for, Polly dear?" "I'm tired, mother, tired of working and waiting. If I'm ever going to have any fun, I want it _now_ while I can enjoy it." "You shouldn't wait another hour if I could have my way; but you know how helpless I am;" and poor Mrs. Snow sighed dolefully, as she glanced about the dingy room and pretty Mary turning her faded gown for the second time. "If Aunt Kipp would give us the money she is always talking about, instead of waiting till she dies, we should be _so_ comfortable. She is a dreadful bore, for she lives in such terror of dropping dead with her heart-complaint that she doesn't take any pleasure in life herself or let any one else; so the sooner she goes the better for all of us," said Polly, in a desperate tone; for things looked very black to her just then. "My dear, don't say that," began her mother, mildly shocked; but a bluff little voice broke in with the forcible remark,-- "She's everlastingly telling me never to put off till to-morrow what can be done to-day; next time she comes I'll remind her of that, and ask her, if she is going to die, why she doesn't do it?" "Toady! you're a wicked, disrespectful boy; never let me hear you say such a thing again about your dear Aunt Kipp." 1 "She isn't dear! You know we all hate her, and you are more afraid of her than you are of spiders,--so now." The young personage whose proper name had been corrupted into Toady, was a small boy of ten or eleven, apple-cheeked, round-eyed, and curly-headed; arrayed in well-worn, gray knickerbockers, profusely adorned with paint, glue, and shreds of cotton. -

Heteroplasmy Variability in Individuals with Biparentally Inherited Mitochondrial DNA

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.26.939405; this version posted February 26, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Heteroplasmy variability in individuals with biparentally inherited mitochondrial DNA Jesse Slonea,¶, Weiwei Zoua,b,¶, Shiyu Luoa,#, Eric S Schmittc,d, Stella Maris Chend, Xinjian Wanga, Jenice Browna, Meghan Bromwella, Yin-Hsiu Chiene, Wuh-Liang Hwue, Pi-Chuan Fanf, Ni-Chung Leee, Lee-Jun Wongc, Jinglan Zhangc,&, and Taosheng Huanga,&,* a Division of Human Genetics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH 45229, USA b Reproductive Medicine Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230022, Anhui, China c Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA d Baylor Genetics, Houston, TX, 77030 e Department of Pediatrics and Medical Genetics, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei 10041, Taiwan f Department of Pediatrics, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei 10041, Taiwan * To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected] ¶ These authors contributed equally to this study. & These authors contributed equally to this study. # Current affiliation: Division of Newborn Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.26.939405; this version posted February 26, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Even Though the Title Is “Mother's” Day, This Day Is Meant to Celebrate

Even though the title is “Mother’s” Day, this day is meant to celebrate all special women in your child’s life whether it is moms, grandmas, aunts, stepmoms, etc. Encourage your child to complete the activities thinking of the special women in their life. Mother’s Day Stories To login to www.myon.com, use the following login information School Name: Brooklyn Reads: Elementary, Username: brooklyn, password: read Time Together- Me and Mom https://www.myon.com/reader/index.html?a=tttr_memom_s14 After reading the story, talk to your child about fun things they like to do with mom, grandma, aunt, etc. I Love you My Bunnies https://www.myon.com/reader/index.html?a=m3_dis1_iloveyoubun After reading, talk to your child about things that their mom (grandma, aunt, etc.) do to help take care of them. Katie Woo- Katie’s Happy Mother’s Day (Gr. 1+) https://www.myon.com/reader/index.html?a=kw_hmd_f15 Max and Zoe Celebrate Mother’s Day (Gr. 1+) https://www.myon.com/reader/index.html?a=mz_motda_f12 Mother’s Day Read Alouds Does a Kangaroo Have a Mother Too? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTgq16pnP08 Repetitive text is great for younger children to “read along” throughout the story Just Me and My Mom https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAghGEZrnDc This video includes text that highlights each word as it is read for beginning readers to read along. You can mute the video for your child to read along. My Mother is Mine https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cifHQFdYq6c Is Your Mama a Llama? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mttOFJWmeM0 Mother’s Day Writing Activities Mother’s Day Movement These stories and poems can be tailored to any special woman in your Hugs and Kisses child’s life.