Voucher-And-Race-Discrimination.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuyahoga County Division of Children & Family

Cuyahoga County Division of Children & Family Services 2018 Community Partners Catholic Charities – Fatima Family Center 6809 Quimby Cleveland, OH 44103 Phone: (216) 361-1244 or (216) 391-0505 Fax: (216) 361-9444 Referrals/TDM Notifications: [email protected] Lead Agency Staff Title Phone Number Email Address Service Areas LaJean Ray Director 216-391-0505 [email protected] Chagrin Falls Village Goodrich - Kirtland Sheila Ferguson Supervisor 440-719-9422 [email protected] Hough (Cleveland Area) Jacquella Lattimore Wrap Specialist 216-855-2179 [email protected] Huntington Valley Hough (Cleveland Area) Sonya Shakir Wrap Specialist 216-214-0197 [email protected] Rhonda DeRusha Wrap Specialist 440-637-2350 [email protected] Zip Codes: 44022, 44103, 44144 Rhonda Wilson Wrap Specialist / Visitation Coach 216-307-9150 [email protected] Deena Reaves Resource Specialist 216-391-0505 [email protected] Catholic Charities – St. Martin De Porres rd 1264 East 123 Street Cleveland, OH 44108 Phone: (216) 268-3909 Fax: (216) 268-0207 Referrals/TDM Notifications: [email protected] or [email protected] Lead Agency Staff Title Phone Number Email Address Service Areas Karnese McKenzie Director 216-268-3909 [email protected] Bratenahl Collinwood Virginia Hearn Associate Director 216-268-3909 x 224 [email protected] Forest Hills Carmen Williams Program Administrator 216-268-3909 x 267 [email protected] Glenville Cynthia Pittman Wrap Specialist 216-268-3909 x 263 [email protected] Zip Codes: 44108, 44110 Vacant -

Cudell Edgewater Plan Hi Res.Pdf

NEIGHBORHOOD2001 MASTER PLAN Cudell Improvement, Inc. CUDELL// EDGEWATER C O N T E N T S THE CONTEXT FOR PLANNING ........................................ 1 The Cudell/Edgewater Neighborhood ............................... 1 Purpose of the Master Plan .................................................. 1 Process and Participants ........................................................ 2 Previous Studies ...................................................................... 3 West 117th Street ............................................................ 3 Former Fifth Church of Christ Scientist .................... 6 Detroit Avenue ................................................................ 6 Lorain Avenue ................................................................. 7 Housing .......................................................................... 10 Historic Districts ........................................................... 10 EXISTING CONDITIONS ...................................................... 12 Neighborhood Demographics ............................................ 13 Zoning and Land Use ........................................................... 19 Residential ...................................................................... 23 Commercial .................................................................... 34 Industry .......................................................................... 37 Institutions and Open Space ....................................... 39 Traffic and Parking .............................................................. -

Ward 14 News ~ Fall 2018, Council Member Jasmin Santana

FALL 2018 | www.ClevelandCityCouncil.org A Message from Councilwoman Jasmin Santana Greetings Ward 14 Resident, City Council took a legislative break this past summer, which allowed me time to get out of City Hall and make deeper connections to the neighborhoods of Ward 14. It was great to walk throughout the community every day, meeting and greeting and listening to your concerns. Over the summer, with the help of block clubs and local activists, we “I am committed to cleaning up, handled hundreds of constituent fixing up and lighting up our complaints, ranging from potholes to trash pickups to neighborhood Ward 14 neighborhoods.” annoyances. their artistic skills to painting trash bins and fire I have to admit, sometimes the work of a hydrants along Fulton Road and Clark Avenue. Engage with Councilwoman public official in a big city can be somewhat The volunteer event marked the first step in challenging, but then I am reminded of the JASMIN SANTANA creating a ward-wide beautification project. words by the late Mother Teresa: “I alone Concejala Jasmin Santana, Distrito 14 I am committed to cleaning up, fixing up cannot change the world, but I can cast a and lighting up our Ward 14 neighborhoods. PHONE/TELÉFONO stone across the waters to create many ripples.” So I’m putting out a call to arms – arms with 216-664-4238 And each of those ripples, the late Robert rolled up sleeves – to help me in this endeavor. EMAIL F. Kennedy once said, is a tiny accent of hope, Together, we can clean up litter and stop illegal [email protected] moving and connecting with other ripples dumping. -

Residential Sales for Cleveland Wards, OCT 2020 Source

Residential Sales for Cleveland Wards, OCT 2020 Source: Cuyahoga County Fiscal Office Prepared by Northern Ohio Data and Information Service (NODIS), Levin College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland State University Statistical 2010 Orig. Final Parcel Parcel Parcel Parcel Planning 2014 2009 Census Land Land Deed Conveyance Conveyance Transfer Receipt Number Address Municipality Zip Area Ward Ward Tract Use Type Use Type Type Price Flag Date Number 140-02-011 3923 E 154 ST Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family WAR $43,000 13-Oct-20 140-02-030 15503 STOCKBRIDGE AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family WAR $62,000 14-Oct-20 140-05-043 16110 STOCKBRIDGE AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family WAR $123,500 21-Oct-20 140-08-013 16309 WALDEN AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family LIM $62,766 5-Oct-20 140-08-070 16316 INVERMERE AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family AFF $0 19-Oct-20 140-09-073 16603 INVERMERE AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family WAR $0 6-Oct-20 140-11-058 17507 THROCKLEY AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family WAR $74,500 13-Oct-20 140-11-087 17308 THROCKLEY AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family WAR $39,400 7-Oct-20 140-13-042 16916 TALFORD AVE Cleveland 44128 Lee-Harvard 1 1 121700 Single family dwelling Single-Family -

Clark-Fultonclark Elem Meeting Hall ! R CLARK AV !

å å Walton Elem Ceska Sin Sokol D West 25th/Clark Retail District Clark-FultonClark Elem Meeting Hall ! R CLARK AV ! å FIRE COMPANY 24 N Æc O ²µ T Community Assets - 2006 L U F å Buhrer Elem Legend Merrick House ! D R Cleveland Municipal Schools å St Rocco Elem N kj O kj Other Schools Lincoln-West High T N å A Miscellaneous R C S EMS ²µ Fire Luther Memorial Elem ! # Health kj Meyer Pool Metro Lofts qÆ Hospital ! Parks (see below) _ Police Steelyard Commons ! Service Shopping Center ! Utilities Æc Library EMS (2005) METROHEALTH MEDICAL CENTER Parks qÆ EMS (2005) Historic District 2ND DISTRICT POLICE HQ ENGLINDALE _ Jones Children Home ! ! Milford Place Æc D Riverside Cemetery EN I ! SO N AV y a w Brooklyn Centre Historic District y B y Æc a w l a Brookside Park T n S a ! H Y C T K 5 E P 2 Aerial: Airphoto USA 2005 & N W O O T L U F T S Clark-Fulton V D N A R I RA Connecting Cleveland3 L O2020 Citywide Plan - Retail District Strategies 7 Cudell W Detroit-Shoreway Ohio City CLARK AV Clark-Fulton T S - Focus redevelopment efforts on West 25th/ H T Clark intersection 5 T 6 - Redevelop vacant & underutilized buildings S and properties D W R - Develop streetscape enhancement plan for 3 7 portions of Clark Ave and West 25th St Tremont - Consolidate Latino-oriented businesses on W West Boulevard West 25th St into regional retail destination D R N D O R T T N S N O A Clark-Fulton H T R L T C U 5 F 2 S Stockyards W - Establish consolidated retail district centered around K-Mart Plaza along West 65th St between West 67th Pl and West 65th St - -

Steps to a Healthier Cleveland 2006 Community Garden Report

Steps to a Healthier Cleveland 2006 Community Garden Report Prepared by: Matthew E. Russell, MNO Center for Health Promotion Research Case Western Reserve University & Morgan Taggart Ohio State University-Cuyahoga County Extension 2/1/2007 Contact Information: Matt Russell Center for Health Promotion Research Case Western Reserve University 11430 Euclid Ave. Cleveland, Ohio 44106 Phone: 216.368.1918 Email: [email protected] Morgan Taggart The Ohio State University Extension Cuyahoga County Office 9127 Miles Road Cleveland, Ohio 44105 Phone: 216.429.8246 Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………….……..………………………………………..3 Map of Steps Intervention Neighborhoods……..………………………………………..4 Introduction………………..………....………………………..………………………….5-7 PART I. Steps Community Urban Garden Network Profiles…………...………..8-24 Steps Garden Summary Data…………..…….…..……………………...25-29 PART II. Cleveland Residents; Food Perceptions (BRFSS Data)……………..30-33 PART III. Resource Development……...….……………………….………………….34 Website Development……………………………… . …………………………… . 35 Citywide Garden Locator Map (Reference Data)…..…………………….36-57 Limitations and Conclusion……………………………………………………….…......58 References…………………………………………………………………………………...59 A p p e n d i x ………………………………………………………………………………… 6 0 Garden Participation Survey……...………………………..……………….. Appendix A Garden Inventory Questionnaire……………………………………….….…Appendix B Acknowledgements A special thanks to the following people for their help and guidance throughout this project…... Cleveland Gardener -

Executive Director's Report

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT Board of Directors September 14, 2018 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AGENDA PRIORITIES & STATUS • NOACA 50th Anniversary • Long-Range Transportation Plan • Communications & Outreach • Legislative & Funding Issues • Overall Work Program (OWP) • Announcements Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increase Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achiev ncreased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility AchievingNOACA Increased Mobility 50TH Achieving IncreasedANNIVERSARY Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achievi ncreased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased Mobility Achieving Increased NOACA 50TH ANNIVERSARY Events conducted this summer • June photo contest • Winning photo served as the banner image for NOACA’s Facebook page in July • NOACA Community Day at the Cleveland History Center (Crawford Auto-Aviation Museum) • Sunday, August 26 • First 100 guests received free admission courtesy of NOACA NOACA 50TH ANNIVERSARY Events coming up: • Trolley tour of NE Ohio using Lake Erie Coastal Ohio Trail app • Part of NARC Executive Directors conference • September 30 • Transportation-oriented film in November • -

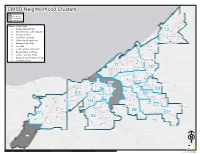

Number Cluster Name 01 Kamm's

CCMMSSDD NNeeiigghhbboorrhhoooodd CClluusstteerrss Oliver H Perry Cleveland Boundary " Cluster Boundary 2012 SPA Boundary North Shore Collinwood 2014 Ward Boundary Memorial " Hannah Gibbons Number Cluster Name " 01 Kamm's - Bellaire-Puritas Ginn Academy 1122 " 02 Detroit Shoreway - Cudell - Edgewater Collinwood-Nottingham 03 Ohio City - Tremont East Clark " Collinwood College Board Academy Euclid Park 04 Clark-Fulton - Stockyards " " Euclid-Green 05 Old Brooklyn - Brooklyn Center Iowa-Maple " Kenneth W Clement Boys' Leadership Academy 06 Broadway - Slavic Village " Glenville Career and College Readiness Academy 07 Lee - Miles " Franklin D Roosevelt 08 Central - Kinsman - Mt. Pleasant " Glenville Patrick Henry 09 Buckeye-Shaker - Larchmere " Michael R White STEM " 10 Glenville - University - Fairfax St.Clair-Superior Willson 11 Downtown - St. Clair-Superior - Hough " Cleveland School of the Arts at Harry E. Davis " Mary M Bethune East Professional Center " 12 Collinwood - Euclid " Daniel E Morgan Wade Park " Case " " Hough 1111 Goodrich-Kirtland Pk Martin Luther King Jr " Mary B Martin School SuccessTech Academy Design Lab - Early College @ Health Careers " MC2STEM " " 1100 Downtown" University Campus International School " John Hay- Cleveland School of Science and Medicine John Hay - Cleveland Early College High School "John Hay - Cleveland School of Architecture and Design George Washington Carver STEM " Marion-Sterling "Jane Addams Business Careers Center Fairfax " Bolton Alfred A Benesch " Central " East Tech Community Wraparound " -

“One in Every Six Women in Cleveland Had Asthma.”

During 2005 through 2009 were twice as high among fe- through 2009, males (16.8%) than males (7.4%). This differ- about one in every ence in current asthma across gender is con- eight (12.7%) Cleveland sistent with state and national data. In addition, adults said that they had rates for both men and women appear to in- currently suffered from crease slightly from 2005-2007 to 2008-2009. asthma during the year See Figure 4 for these local results. For 2005- www.prchn.org surveyed. Overall, at least 2007, current asthma prevalence was 15.3% for one in every six (17.6%) said women, 7.0% for men compared to 18.4% for they ever had asthma at some women and 7.7% for men for 2008-2009. time during their lifetime. These estimates are based on new anal- “One in every six women in yses of data from the Cleveland- Cuyahoga County Behavioral Risk Cleveland had asthma.” Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) collected from more than 6,300 Cleve- The local data also confirm the small but land residents who participated in the steady increase in current asthma as adults survey between 2005-2009. increase in age up to 65 years (Figure 4). At age The first condition, “current asthma”, is 65 and after, the rate of current asthma drops defined as a wheeze with tight, constricted slightly, consistent with data for Ohio and na- (Pittsburgh) and Wayne County (Detroit). See airways in the past year. The second condi- tionwide. Figure 3. We make this conclusion because the tion, “lifetime asthma”, is defined as having Locally, current asthma rates do not appear 95% confidence interval for Cleveland does not been diagnosed with asthma during their to differ by race. -

Quit Claim Transfers, by Place, AUG 2020 Source: Cuyahoga County

Quit Claim Transfers, by Place, AUG 2020 Source: Cuyahoga County Fiscal Office Prepared by Northern Ohio Data and Information Service (NODIS), Levin College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland State University Cleveland Cleveland 2010 Parcel Parcel Parcel Parcel Cleveland 2014 2009 Census Land Deed Conveyance Conveyance Transfer Number Address Municipality Zip Neighborhood Ward Ward Tract Use Type Type Price Flag Date 202-32-039 630 REVERE DR Bay Village 44140 130104 Single family dwelling QTC $0 27-Aug-20 203-28-099 329 GLEN PARK DR Bay Village 44140 130105 Single family dwelling QTC $0 28-Aug-20 204-03-029 442 LAKE FOREST DR Bay Village 44140 130106 Single family dwelling QTC $0 18-Aug-20 204-24-004 23416 LAKE RD Bay Village 44140 130106 Single family dwelling QTC $337,500 14-Aug-20 204-25-804C 23230 SHEPPARD'S POINT Bay Village 44140 130106 Residential condominiums QTC $0 20-Aug-20 204-26-043 23717 EAST OAKLAND RD Bay Village 44140 130106 Single family dwelling QTC $0 27-Aug-20 741-05-067 23600 EAST GROVELAND RD Beachwood 44122 131103 Single family dwelling QTC $0 18-Aug-20 741-15-018 25485 PENSHURST DR Beachwood 44122 131103 Single family dwelling QTC $0 19-Aug-20 741-16-026 24082 TIMBERLANE DR Beachwood 44122 131103 Single family dwelling QTC $0 26-Aug-20 741-16-038 2510 BUCKHURST DR Beachwood 44122 131103 Single family dwelling QTC $0 11-Aug-20 741-26-954C 2 STRATFORD CT Beachwood 44122 131104 Residential condominiums QTC $0 14-Aug-20 742-08-074 21211 HALWORTH RD Beachwood 44122 131102 Single family dwelling QTC $0 4-Aug-20 742-09-327 22655 -

Preparing for Growth an Emerging Neighborhood Market Analysis Commissioned by Mayor Frank G

Preparing for Growth An Emerging Neighborhood Market Analysis Commissioned by Mayor Frank G. Jackson for the City of Cleveland By Richey Piiparinen, Kyle Fee1, Charlie Post, Jim Russell, Mark Salling and Tom Bier CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY The Center for Population Dynamics 1 Kyle Fee is a Regional Community Development Advisor at the Federal Reserve Back of Cleveland In anticipation of the development of a Neighborhood Transformation Initiative, in 2016, Mayor Frank G. Jackson commissioned Cleveland State University’s Center for Population Dynamics to analyze the City of Cleveland housing market. The resulting study, “Preparing for Growth,” provides a foundation for the Mayor’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative acknowledging neighborhoods where private investment is strong but, and most significantly, identifying emerging neighborhood markets where focused planning and the leverage of public dollars will attract private investment to the benefit of existing residents and businesses in these neighborhoods. i Table of Contents Key Findings Page 2 Purpose Page 3 What is Global becomes Local Page 3 Demographic Trends in Cleveland, 1970 to 2010 Page 5 Real Estate Trends in Cleveland Islands of Renewal Page 12 Spreading the Wealth: The Consumer versus Producer City Approach Page 14 Preparing for Growth Page 20 1 Key Findings • Greater Cleveland is transitioning into a knowledge economy, led by the region’s growing “eds and meds” sector. This transition is underpinning the City of Cleveland—which houses the region’s top hospitals and universities—as a place of importance in terms of reinvestment. • The economic transition has corresponded with demographic changes in a number of Cleveland neigh- borhoods, particularly over the last 10 years. -

Community Health Needs Assessment Implementation Plan: Addressing the Needs of the 2019-2022 Columbiana County CHNA

Community Health Needs Assessment Implementation Plan: Addressing the needs of the 2019-2022 Columbiana County CHNA East Liverpool City Hospital PRIME HEALTHCARE SERVICES 425 W 5th St. East Liverpool, OH 43920 East Liverpool City Hospital 425 W 5th Street East Liverpool, OH 43920 2019-2022 Community Health Needs Assessment’s Implementation Plan for East Liverpool City Hospital As Required by Internal Revenue Code § 501(r)(3) Name and EIN of Hospital Organization Operating Hospital Facility: East Liverpool City Hospital- EIN 34-0714583 Date Implementation Plan Approved July 8th, 2020 By Authorized Governing Body: Authorized Governing Body: Recommendation for Approval on June 25th, 2020 by the East Liverpool City Hospital Governing Board Approval Given July 8th, 2020 by the ELCH Executive Team Comments: Written comments about the Columbiana County Health Needs Assessment and/or the ELCH Implementation Plan may be submitted to Jayne Rose, CNO 425 W 5th St. East Liverpool, Ohio 43920; or by email [email protected] EAST LIVERPOOL CITY HOSPITAL: 2019-2022 Implementation Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………….. Page 1- 2 II. MOBILIZING FOR ACTION: ASSESSMENTS & PRIORITIZATION PROCESS Page 2- 7 III. ELCH’S IMPLEMENTATION PLANNING PROCESS……………………………… Page 7-9 IV ALIGNMENT WITH STATE, NATIONAL & COUNTY PRIORITIES………………. Page 9-12 V. ACTION STEPS RECOMMENDED IN THE 2019-2022 CHIP…………………….. Page 12- 13 VI. RESOURCES TO ADDRESS NEEDS..………………………………………………. Page 14- 15 VII. ELCH IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES TO ADDRESS HEALTH NEEDS…... Page 16- 25 VIII. NEEDS NOT ADDRESSED IN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN.…………………….…. Page 26- 27 IX. PROGRESS & MEASURING OUTCOMES………………………………………….. Page 27- 28 X. APPENDIX I & II……………………………………………………………………….... Page 28- 38 EAST LIVERPOOL CITY HOSPITAL: 2019-2022 Implementation Plan I.