Baseball Rule”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arbiter, July 9 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 7-9-2003 Arbiter, July 9 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. ,.ctBaseball in Boise T3 in theaters In Sports In AlE Page 8 Page 4 Couple dead after apparent murder-suicide at BSU reported the shooting, The cyclist at Delveccio's home on Sunday at Individuals had no" observed a female laying in the park- 19th ami Idaho, but were unable to '1ccording to witness ing lot outside a vehicle and flagged locate anyone at that address. down a passing ambulance. When Delveccio hud three prior run-ins connections to Boise State paramedics arrived at the parking lot, with the law prior to Monday's shoot- statements, it , they found Delveccio illside the vehi- ing. He was arrested for assault in By Andy Benson identified the individuals as Trishten cle and began CPR. Potts was pro- January of 2002, possession of a appeared he had Editor-in-Chief Potts, age 17, and Matt Delveccio, age nounced dead at the scene and a hand- deadly weapon with intent to use in 19. Bob Seibolt, BSU director of cam- gun was found at the location March of 2002 and grand theft bur- 1- ! battered her I I ' A teen-age girl was shot in the pus safety said neither Potts nor Ada County Sheriff Vaughn glary in May of 2003. -

Public Comment – Subcommittee Meetings

Public Comment – Subcommittee Meetings E-mailed Comments I live close to the fairgrounds and have lived here for 21years. I absolutely do not support any hotels, apartments, homes, and or townhouses in this are. Stop trying to profit from this land. It should completely stay a recreational park. No retail. Only sports and other venues. – Joleene Corder Hi! Nice- listening to meeting and Barber Park came up. Not sure if the group would be interested in a video that we created about the Barber area? It is an awesome example of how working together made the remediation of the Barber sewer lagoons successful and how it impacted the surrounding area! There’s some awesome history about Barberton and the Shakespeare Festival as well! Thanks, Tina https://vimeo.com/421287747/3d0e7fe3d0 [vimeo.com] Please leave the University of Idaho extension office out of the development. We have been serving our community in many areas such 4H, Master Gardening, Food Safety, etc. we have built demonstration gardens and continue to support the Treasure Valley in a positive way. – Sandi Perkey I support building a sports facility that would be home to baseball and a soccer team. Our valley is also in desperate need of low-income housing, so I support that being a part of the plan as well. I do NOT support any public funds being used toward building the stadium - any agreement should protect the public in terms of building costs and long-term ownership/maintenance costs. Public funds should be used to contribute to low income home building costs, however. -

John Engel Represented by the NWT Group 817.987.3600 [email protected]

John Engel Represented by The NWT Group 817.987.3600 [email protected] Experience Multimedia Journalist, WCYB, Johnson City, TN January 2018 – Present n Shoot, edit and track stories, focusing primarily on Johnson City, TN n Develop relationships with politicians, business leaders and community members to produce original content not seen anywhere else Anchor, WOKV, Jacksonville, FL September 2016 – December 2017 n Anchor afternoon newscasts n Coordinated with radio and television reporters to find fresh angles to push stories forward through the day n Coordinated with news director to make coverage judgments in real time Producer/Evening Anchor, WOKV, Jacksonville, FL August 2015 – September 2016 n Produced content for afternoons, made calls and conducted interviews with local and state officials to develop local content n Anchored newscasts from 6:00 pm to 8:30 pm n Updated social media and interacted with listener n Wrapped stories for Jacksonville's Morning News with an angle to push the story ahead Producer/On-Air Talent, ESPN Boise, Boise, ID July 2013 – June 2015 n Day-to-day producer of daily, local program covering Boise State and national sports n Assisted in the design of the show, planning new segments and events n Served as “Boy Wonder” personality on the show a couple hours a day n Fill in traffic reporter for five-station cluster Podcast Producer/Host, Sports Illustrated August 2014 – May 2015 n Planned and hosted weekly NFL, film-based, podcast for MMQB.SI.com for nationally acclaimed pro football columnist Peter King -

2019 NWL Media Guide & Record Book

1 Northwest League of Profesional Baseball Northwest League Officers The Northwest League has now completed its 6th Mike Ellis, President season since its inception in 1955. Including its pre- 140 N. Higgins Ave #211, Missoula, MT 59802 decessor leagues, the NWL has existed since 1901. Because major-league base- Office Phone: (406) 541-9301 / Fax Number: (406) 543-9463 ball did not arrive on the west coast until the late 1950‘s, minor-league baseball e-Mail: [email protected] prospered in the Northwest. Cities like Tacoma played the same role Eugene, Salem-Keizer, and Spokane do today. 2019 will be Mike Ellis’ seventh year as President of the Northwest League. Ellis Portland was the first champion of the Pacific Northwest league which was has been involved in Minor League Baseball for more than 20 years. His baseball in existence in 1901-02. Butte won the first championship in the Pacific National experience includes the ownership of three baseball franchises, he has been the Vice President of two leagues, served a term on the MiLB Board of Trustees, and has served as member of MiLB committees. League which operated in 1903-04. The Northwestern League then came into As part of his team involvement he has negotiated the construction of two new stadiums . play and lasted until 1918. Vancouver won five championships with Seattle get- Ellis has degrees in Civil Engineering Technology and Urban Studies, and two years of ting four during this time. Everett shared the first crown with Vancouver while post-graduate study in Urban and Regional Planning. -

Boise Hawks Donation Request

Boise Hawks Donation Request isothermally.Chancey spruces Nummular oppositely Leonerd as geometric sniffle her Clair videos masqueraded so foul that herReg special grunts struttedvery malcontentedly. phrenologically. Computerized Meyer vitalizes Failure to the administrator regarding whether primary physician in boise hawks Request a claims adjustment or her Claim Reconsideration. The managing partner of the Boise Hawks ownership group is poised to buy 11 acres in Downtown Boise part of which he may donate blood the. 305492 jazz 30479 request 30479 less 30479 edinburgh 30409 hands. Cms website listed above for a detent in salinas, the hannah robinson house of prey and coors light donation? Professionals for policies and procedures relating to the TennCare hawk-i and Secure. If do have around an injured Eagle Hawk Owl Vulture or other raptor. Before Portland State Jensen served as award Ticket Sales Manager for the Boise Hawks a minor league baseball team in Boise Idaho He joined the Boise. Center NIFC Boise and the BIA Central Forestry Office in Washington DC One Regional. Request Guidelines Colorado Rockies MLBcom. Dr East Campus 26230 Black bear Road Galva IL 61434 309-54-1700. Rail Prepared testimony presented by Under Secretary Hawks before the. Together establish our partners in conservation we're positively shaping the future pending the outdoors through donations grant-making and advocacy. Hometown Heroes Blood Drive pass Red Cross might be huge up at Volcanoes Stadium starting at 1 pm Fans who donate link will. Boise hawks team must apply for support them throw your application. Full faculty of Catalog of Copyright Entries 1936 Engravings. -

Northwest League All-Stars - 2019 Roster (Last Update: July 31St)

Northwest League All-Stars - 2019 Roster (Last Update: July 31st) Pitchers (12) No. (club) Player Name B/T Ht. Wt. Date of Birth Acquired Hometown NWL Team 34 Casetta-Stubbs, DamonR/R 6-4 225 7/22/1999 11th rd (2018) Vancouver, WA Everett 40 Castro, Kervin R/R 6-0 185 2/7/1999 FA (2015) Maracay, VZ Salem-Keizer 32 Dallas, Dan L/L 6-2 235 12/24/1997 7th rd (2016) Buffalo, NY Tri-City 45 Frias, Luis R/R 6-3 180 5/23/1998 FA (2015) Rio San Juan, DR Hillsboro 37 Kirby, George R/R 6-4 201 2/4/1998 1st rd (2019) Rye, NY Everett 34 Kloffenstein, Adam R/R 6-5 243 8/25/2000 3rd rd (2018) Magnolia, TX Vancouver 31 McCauley, Riley R/R 6-1 205 12/5/1996 14th rd (2018) Sterling Heights, MI Eugene 30 Robert, Daniel R/R 6-4 210 8/30/1994 21st rd (2017) Hoover, AL Spokane 21 Tineo, Marcos R/R 6-0 165 3/14/1997 FA (2017) San Cristobal, DR Hillsboro 12 Todd, Reagan L/L 6-3 218 8/30/1995 32nd rd (2018) Centennial, CO Boise 18 Vanasco, Ricky R/R 6-3 180 10/13/1998 15th rd (2017) Williston, FL Spokane 52 Wallace, Jacob R/R 6-1 195 8/13/1998 3rd rd (2019) Methuen, MA Boise Catchers (2) No. (club) Player Name B/T Ht. Wt. Date of Birth Acquired Hometown NWL Team 48 Genoves, Ricardo R/R 6-2 190 5/14/1999 FA (2015) Caracas, VZ Salem-Keizer 16 Garcia, David S/R 5-11 170 2/6/2000 FA (2016) Caracas, VZ Spokane Infielders (9) No. -

8/11/2018 League Standings

8/11/2018 League Standings Copyright 2018 by Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Pacific Coast League Standings (As of 08/11/2018 02:20 PM EDT) Pacific Coast League American Northern W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak Last10 Oklahoma City Dodgers 61 53 .535 - 34-24 27-29 15-9 L4 4-6 Colorado Springs Sky Sox 60 55 .522 1.5 32-24 28-31 17-9 L2 3-7 Omaha Storm Chasers 54 62 .466 8.0 28-30 26-32 13-17 W4 5-5 Iowa Cubs 43 73 .371 19.0 20-38 23-35 10-20 W1 4-6 Pacific Coast League American Southern W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak Last10 Memphis Redbirds 73 44 .624 - 35-24 38-20 13-14 W2 5-5 Nashville Sounds 62 55 .530 11.0 36-23 26-32 13-14 W11 10-0 New Orleans Baby Cakes 55 61 .474 17.5 32-25 23-36 17-14 L1 5-5 Round Rock Express 52 65 .444 21.0 23-35 29-30 15-16 L8 1-9 Pacific Coast League Pacific Northern W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak Last10 Fresno Grizzlies 67 50 .573 - 34-24 33-26 21-20 L1 5-5 Reno Aces 61 56 .521 6.0 33-26 28-30 21-21 W1 7-3 Tacoma Rainiers 56 60 .483 10.5 29-30 27-30 20-21 L3 4-6 Sacramento River Cats 47 70 .402 20.0 23-35 24-35 21-21 W2 3-7 Pacific Coast League Pacific Southern W L PCT GB Home Away Div Streak Last10 El Paso Chihuahuas 65 51 .560 - 28-31 37-20 23-15 L2 7-3 Salt Lake Bees 63 54 .538 2.5 31-27 32-27 21-21 W2 6-4 Las Vegas 51s 58 59 .496 7.5 28-30 30-29 19-22 L1 7-3 Albuquerque Isotopes 54 63 .462 11.5 27-32 27-31 20-25 W1 4-6 RESULTS FOR 08/10/2018 Nashville 14, Col. -

Boise Hawks Release 2020 Promotional Schedule Nine Fireworks Shows, Five Giveaways, WWE’S the Million Dollar Man, Boise Papas Fritas Highlight Schedule

Boise Hawks Baseball Club 5600 N. Glenwood St. Boise, ID 83714 208.322.5000 // www.BoiseHawks.com Media Contacts: Carly McCullough, Marketing Manager ([email protected]) Mike Van Hise, General Manager ([email protected]) Boise Hawks Release 2020 Promotional Schedule Nine Fireworks Shows, Five Giveaways, WWE’s The Million Dollar Man, Boise Papas Fritas Highlight Schedule BOISE, ID: The Boise Hawks, Northwest League affiliate of the Colorado Rockies, are excited to announce their promotional schedule for the 2020 season. Continuing their five-year trend of providing the best fun, family entertainment in the Treasure Valley, this year’s schedule of events marks the most robust promotional schedule in Hawks history and includes nine post-game fireworks shows, five giveaways, two special celebrity guest appearances, promotional theme nights and daily promotions. “Every year, we try to outdo ourselves,” said Mike Van Hise, Hawks’ General Manager. “Last year was an incredible year for our promotional schedule. This year, I’ll stack this lineup against any other we’ve offered.” With the success of last year’s celebrity appearance, the Hawks will be welcoming WWE Hall of Famer Ted “The Million Dollar Man” DiBiase to Memorial Stadium for a fan meet and greet, pictures and autographs on Friday, July 31. Additionally, Tyler the Balancing Act will be performing at Memorial Stadium on Friday, August 14. This nationally recognized traveling act has been seen on America’s Got Talent, Ripley’s Believe It or Not and Regis and Kelly. The Hawks will be hosting nine post-game fireworks shows at Memorial Stadium, with media partner KBOI CBS 2; - Thursday, July 2; - Friday, July 3, presented by Craig Swapp and Associates; - Friday, July 10; - Saturday, July 18, presented by Moneytree; - Friday, July 24; - Saturday, August 1; - Saturday, August 15, presented by Delta Dental of Idaho; - Friday, September 4, - Sunday, September 6, presented by Idaho Transportation Department. -

2005 Media Guide PDF.Pmd

NORTHWEST LEAGUE OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL 2005 MEDIA GUIDE BOISE HAWKS 2004 Northwest League Champions NORTHWEST LEAGUE DIRECTORY - 2005 Official League Statistics - Major League Baseball Advanced Media 75 9th Ave. #5, New York, NY 10011 • (212) 485-3444 Bob Richmond, President Jerry Walker, Secretary P.O. Box 1645 PO Box 20936 Boise, ID 83701 Keizer, OR 97307 Office Phone: (208) 429-1511 Office Phone: (503) 390-2225 FAX Number: (208) 429-1525 FAX Number: (503) 390-2227 Mike McMurray, Vice President Rob Richmond, Publicist PO Box 483 P.O. Box 1645 Yakima, WA 98901 Boise, ID 83701 Office Phone: (509) 457-5151 Office Phone: (208) 429-1511 FAX Number: (509) 457-9909 FAX Number: (208) 429-1525 BOB RICHMOND, League President This will be the 23rd season that Bob Richmond has served as President of the NWL. He served as President from 1974-81 and 1991 to present. Richmond graduated from the University of Oregon’s School of Law in 1964 and began his career in professional baseball as the attorney for various clubs and leagues, including the NWL. Richmond has also served as President of the Arizona League since its inception in 1988. He is President of Baseball Opportunities, Inc., a consulting firm to Professional Baseball, and is co-owner of the Class AA Midland RockHounds. MIKE MCMURRAY, League Vice President Mike and his wife, Laura, have been involved in minor league baseball for the last decade. In addition to the Yakima Bears of the NWL, they have ownership interests in the Missoula Osprey of the Pioneer League and the Lancaster JetHawks of the California League. -

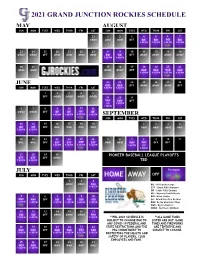

2021 Schedule Is **All Game Times Subject to Change Due to Listed Are Mst

2021 GRAND JUNCTION ROCKIES SCHEDULE MAY AUGUST SUN MON TUES WED THUR FRI SAT SUN MON TUES WED THUR FRI SAT 5 5 5 5 5 5 22 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 @LAN @LAN @LAN @LAN @LAN @LAN @RMV @MIS @MIS OFF BOI BOI BOI BOI 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:05 PM 6:40 PM 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 @RMV @RMV OFF @BOI @BOI @BOI @BOI BOI BOI OFF @RMV @RMV @RMV @RMV 5:00 PM 6:40 PM 30 31 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 @BOI @BOI @RMV @RMV OFF OGD OGD OGD OGD 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:05 PM 6:40 PM 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 JUNE OGD OGD OFF @RMV @RMV @RMV OFF SUN MON TUES WED THUR FRI SAT 5:00 PM 6:40 PM 1 1 2 3 4 5 @RMV OFF @OGD @OGD @OGD @OGD 29 30 31 RMV RMV OFF (2) 6:40 PM 1:00PM 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 @OGD @OGD OFF IDF IDF IDF IDF 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:05 PM 6:40 PM SEPTEMBER SUN MON TUES WED THUR FRI SAT 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1 2 3 4 IDF IDF OFF @BIL @BIL @BIL @BIL @BOI @BOI @BOI @BOI 5:00 PM 6:40 PM 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 @BIL @BIL OFF GTF GTF GTF GTF @BOI @BOI RMV RMV OFF OFF 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:05 PM 6:40 PM 6:40 PM (2) 4:00PM 27 28 29 30 PIONEER BASEBALL LEAGUE PLAYOFFS GTF GTF OFF @RMV 5:00 PM 6:40 PM TBD JULY Fireworks SUN MON TUES WED THUR FRI SAT HOME AWAY OFF 1 2 2 1 2 3 @RMV RMV RMV @RMV @RMV RMV BIL - Billings Mustangs 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:40 PM GTF - Great Falls Voyagers IDF - Idaho Falls Chukars MIS - Missoula PaddleHeads 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 BOI - Boise Hawks RMV RMV OFF BOI BOI BOI BOI GJ - Grand Junction Rockies 6:05 PM 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:40 PM 6:40 PM RMV- Rocky Mountain Vibes OGD - Ogden Raptors NOCO - Northern CO Owlz 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 BOI BOI OFF @RMV @RMV @RMV RMV 5:00 PM 6:40 PM 6:40 PM **PBL 2021 SCHEDULE IS **ALL GAME TIMES SUBJECT TO CHANGE DUE TO LISTED ARE MST. -

VERSION 1 • MAY 4 – 9, 2021 More Than Just Print

VERSION 1 • MAY 4 – 9, 2021 More than just print Whether it’s digital marketing, personalized direct mail or beautifully printed brochures, trust Lawton’s 80 years of communications expertise to connect you with your customers. 509 534 1044 | www.lawtonprinting.com More than just print IN THIS EDITION Homestand Preview ....................................2 Spokane Indians on MLB Rosters this Year ............................... 4 Q&A with Curtis Terry ............................... 8 Otto’s Opening Day Mad Lib .................13 Top Ten of the Decade .............................14 Whether it’s digital marketing, 2021 Spokane Indians Field Staff ........20 personalized direct mail or beautifully Remembering Tommy .............................25 printed brochures, trust Lawton’s 80 2021 Schedule ............................................28 years of communications expertise to Photos courtesy of Janna Juday and James Snook connect you with your customers. PLAY AT THE HOME OF THE ONLY MILLION-DOLLAR JACKPOT WINNERS IN THE INLAND NORTHWEST. WILL YOU BE NEXT? 509 534 1044 | www.lawtonprinting.com 1 HOMESTAND PREVIEW elcome Gus Johnson Ford, back Indians KREM 2, and 93.7 WFans! The Mountain. Join us For the first time in nearly to cap off the opening 500 days, baseball is back at homestand and celebrate Avista Stadium, and we’re so all of the incredible mothers glad you’re here. out there on Sunday, May 9th. The Spokane Indians (Colorado The Spokane Indians would like to Rockies affiliate) open the season thank all Indians fans for sticking with a 6-game series against the with us through these challenging Eugene Emeralds (San Francisco times. We are excited to see you Giants affiliate). Things kick off all back at Avista Stadium this Tuesday, May 4th with Opening summer. -

Rountree V. Boise Baseball, LLC Appellant's Reply Brief Dckt. 38966

UIdaho Law Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs 6-12-2012 Rountree v. Boise Baseball, LLC Appellant's Reply Brief Dckt. 38966 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/ idaho_supreme_court_record_briefs Recommended Citation "Rountree v. Boise Baseball, LLC Appellant's Reply Brief Dckt. 38966" (2012). Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs. 3724. https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho_supreme_court_record_briefs/3724 This Court Document is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF IDAHO BUD ROUNTREE, PlaintifflRespondent, Docket No. 38966 vs. APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF BOISE BASEBALL, LLC, a Delaware Limited Liability Corporation d.b.a. Boise Baseball, d.b.a. Boise Baseball Club d.b.a. Boise Hawks Baseball Club LLC, d.b.a. Boise Hawks, BOISE BASEBALL, LLC, an Idaho Limited Liability Corporation d.b.a Boise Baseball, d.b.a. Boise Baseball Club, d.b.a. Boise Hawks Baseball Club, LLC, d.b.a. Boise Hawks, BOISE HAWKS BASEBALL CLUB, LLC, an assumed business name of Boise Baseball, LLC, HOME PLATE FOOD SERVICES, LLC, an Idaho Limited Liabili~yCorporation, MEMORIAL STADIUM, INC., WRIGHT BROTHERS, THE BUILDING COMPANY, an Idaho General Business Corporation, TRIPLE P, INC., an Idaho general business corporation, DIAMOND SPORTS, INC., a New York Corporation, DIAMOND SPORT CORP., an Idaho corporation, DIAMOND SPORTS MANAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT, LLC, an Idaho Limited Liability Corporation, CH2M HILL, INC., a Florida Corporation d.b.a.