Greeneland the Cinema of Graham Greene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Study of John Galsworthy's Justice As a Realistic Exposure of the English

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:5 May 2019 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Study of John Galsworthy’s Justice as a Realistic Exposure of the English Society Kailas Vijayrao Karnewar, M.A., NET College Road, Snehnagar, Vasmath Dist.- Hingoli. Pin- 431512 [email protected] ================================================================== Abstract John Galsworthy was an English playwright of 20th century. Alike G. B. Shaw he used drama as a vehicle for assigning communal criticism in each of his plays, he uncovered some social illness or other. John Galsworthy’s conception of drama is grounded on realism and general sense of morals. He supposed that drama is a noteworthy art form and capable of inspiring the attention and conveying consciousness of honorable ideologies in human life. Being a law graduate he was conscious of the severe restriction of a legalistic approach to men and matters. Galsworthy also becomes victim of rigid law and rigid society, since he was not married to his lover, Ada. In Justice he exposes all evil of the society like rigid divorce law, rigidity of society, solitary confinement and injustice done to prisoner. Galsworthy presented it by using naturalistic technique. Therefore, basic aim of this paper is to study the ills of English society which caused the demise of the main character Falder. Keywords: John Galsworthy, Justice, Realistic, English society, naturalistic technique, rigid law Introduction John Galsworthy is the best eminent problem writer and novelist in the 20th century. Like Bernard Shaw and his forerunner Ibsen, Galsworthy also presented some boiling problems or other in all his plays. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/27/2021 06:19:09PM Via Free Access

Boys, ballet and begonias: The Spanish Gardener and its analogues alison platt T S S, an American film of 1999 from an Indian director, M. Night Shyamalan, with an all-American star (Bruce Willis), seems a very long way from British cinema of the 1950s.1 But the boy in this film (Haley Joel Osment) seems almost a revenant from the British post-war era, with his lack of teenage quality, his innocence of youth culture and, more importantly, his anguished concern for and with the adult (Willis) whom he befriends. Here there is something of Carol Reed’s The Fallen Idol (1948), Anthony Pélissier’s The Rocking Horse Winner (1949), Philip Leacock’s The Spanish Gardener (1956) and other films of the period that centre upon the child/adult relationship or incorporate it as a theme: Anthony Asquith’s The Winslow Boy (1948) and The Browning Version (1951), and Philip Leacock’s The Kidnappers (1953). Perhaps the template for this type of isolated child is Pip in David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946). Anthony Wager as young Pip seems an irrevocably old-fashioned child victim, the Little Father Time of Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, as does John Howard Davies asking for more in Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948). This sensitive-looking child returns in The Sixth Sense and indeed in another film of 1999, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia. Neither of the children who feature in these films exemplifies today’s idea of ‘normal’ children in cinema, which is based on a concept of young, tough ‘kids’ that does not show children as people. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

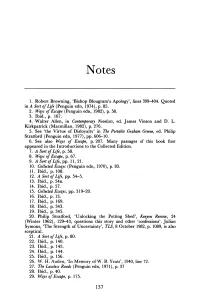

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

"Sounds Like a Spy Story": the Espionage Thrillers of Alfred

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions 4-29-2016 "Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969) Kimberly M. Humphries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Humphries, Kimberly M., ""Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969)" (2016). Student Research Submissions. 47. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/47 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SOUNDS LIKE A SPY STORY": THE ESPIONAGE THRILLERS OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND AMERICAN SOCIETY, FROM THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934) TO TOPAZ (1969) An honors paper submitted to the Department of History and American Studies of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Kimberly M Humphries April 2016 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Kimberly M. -

Page 1 Table of Cases (References Are to Pages in the Text.) 16 Casa

Table of Cases (References are to pages in the text.) 16 Casa Duse, LLC v. Merkin, 791 F.3d 247 (2d Cir. 2015) .....6-14 A A Slice of Pie Prods. LLC v. Wayans Bros. Entm’t, 487 F. Supp. 2d 33 (D. Conn. 2007) ......................... 3-7, 3-8, ........................................................................7-3, 7-4, 7-5, 17-7 Aaron Basha Corp. v. Felix B. Vollman, Inc., 88 F. Supp. 2d 226 (S.D.N.Y. 2000) .................... 10-18, 17-10 Accolade, Inc. v. Distinctive Software, Inc., 1990 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 14305 (N.D. Cal. 1990) ..............8-16 Acker v. King, 112 U.S.P.Q.2d 1220 (D. Conn. 2014) ............1-11 Act Grp., Inc. v. Hamlin, No. CV-12-567-PHX, 2014 WL 1285857 (D. Ariz. Mar. 28, 2014) ............. 3-29, 6-3 Act Young Imps., Inc. v. B&E Sales Co., 667 F. Supp. 85 (S.D.N.Y. 1986) .....................................16-15 Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. v. Jostens, Inc., 988 F. Supp. 289 (S.D.N.Y. 1997), aff’d, 155 F.3d 140 (2d Cir. 1998) ............1-6, 2-15, 2-17, 9-3 Addison-Wesley Publ’g Co. v. Brown, 223 F. Supp. 219 (E.D.N.Y. 1963) .........2-27, 6-6, App. B-14 Advanced Tech. Servs., Inc. v. KM Docs, LLC, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 134567 (N.D. Ga. Apr. 9, 2013) ......................................................17-4 Adventures in Good Eating v. Best Places to Eat, 131 F.2d 809 (7th Cir. 1942) ................................................1-5 (Osterberg/Osterberg, Rel. #13, 5/16) T–1 SUBSTANTIAL SIMILARITY IN COPYRIGHT LAW Alberto-Culver Co. -

'Duncanville' Is A

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! February 14 - 20, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 The animated, Amy Poehler- T M O T H U Q Z A T T A C K P Your Key produced 2 x 3" ad P U B E N C Y V E L L V R N E comedy R S Q Y H A G S X F I V W K P To Buying Z T Y M R T D U I V B E C A N and Selling! “Duncanville” C A T H U N W R T T A U N O F premieres 2 x 3.5" ad S F Y E T S E V U M J R C S N Sunday on Fox. G A C L L H K I Y C L O F K U B W K E C D R V M V K P Y M Q S A E N B K U A E U R E U C V R A E L M V C L Z B S Q R G K W B R U L I T T L E I V A O T L E J A V S O P E A G L I V D K C L I H H D X K Y K E L E H B H M C A T H E R I N E M R I V A H K J X S C F V G R E N C “War of the Worlds” on Epix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bill (Ward) (Gabriel) Byrne Aliens Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Helen (Brown) (Elizabeth) McGovern (Savage) Attack ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Catherine (Durand) (Léa) Drucker Europe Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Mustafa (Mokrani) (Adel) Bencherif (Fight for) Survival County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Sarah (Gresham) (Natasha) Little (H.G.) Wells Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, ‘Duncanville’ is a new Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Bourgeois Like Me

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Bourgeois Like Me: Architecture, Literature, and the Making of the Middle Class in Post- War London A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Elizabeth Marly Floyd Committee in charge: Professor Maurizia Boscagli, Chair Professor Enda Duffy Professor Glyn Salton-Cox June 2019 The dissertation of Elizabeth Floyd is approved. _____________________________________________ Enda Duffy _____________________________________________ Glyn Salton-Cox _____________________________________________ Maurizia Boscagli, Committee Chair June 2019 Bourgeois Like Me: Architecture, Literature, and the Making of the Middle Class in Post- War Britain Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Floyd iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the incredible and unwavering support I have received from my colleagues, friends, and family during my time at UC Santa Barbara. First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their guidance and seeing this project through its many stages. My ever-engaging chair, Maurizia Boscagli, has been a constant source of intellectual inspiration. She has encouraged me to be a true interdisciplinary scholar and her rigor and high intellectual standards have served as an incredible example. I cannot thank her enough for seeing potential in my work, challenging my perspective, and making me a better scholar. Without her support and guidance, I could not have embarked on this project, let alone finish it. She has been an incredible mentor in teaching and advising, and I hope to one day follow her example and inspire as many students as she does with her engaging, thoughtful, and rigorous seminars. -

MARIUS by Marcel Pagnol (1931) Directed by Alexander Korda

PRESS PACK CANNES CLASSICS OFFICIAL SELECTION 2015 MARIUS by Marcel Pagnol (1931) Directed by Alexander Korda Thursday 21 May 2015 at 5pm, Buñuel Theatre Raimu and Pierre Fresnay in Marius by Marcel Pagnol (1931). Directed by Alexander Korda. Film restored in 2015 by the Compagnie Méditerranéenne de Films - MPC and La Cinémathèque Française , with the support of the CNC , the Franco-American Cultural Fund (DGA-MPA-SACEM- WGAW), the backing of ARTE France Unité Cinéma and the Archives Audiovisuelles de Monaco, and the participation of SOGEDA Monaco. The restoration was supervised by Nicolas Pagnol , and Hervé Pichard (La Cinémathèque Française). The work was carried out by DIGIMAGE. Colour grading by Guillaume Schiffman , director of photography. Fanny by Marcel Pagnol (Directed by Marc Allégret, 1932) and César by Marcel Pagnol (1936), which complete Marcel Pagnol's Marseilles trilogy, were also restored in 2015. "All Marseilles, the Marseilles of everyday life, the Marseilles of sunshine and good humour, is here... The whole of the city expresses itself, and a whole race speaks and lives. " René Bizet, Pour vous , 15 October 1931 SOGEDA Monaco LA CINÉMATHÈQUE FRANÇAISE CONTACTS Jean-Christophe Mikhaïloff Elodie Dufour Director of Communications, Press Officer External Relations and Development +33 (0)1 71 19 33 65 +33 (0)1 71 1933 14 - +33 (0)6 23 91 46 27 +33 (0)6 86 83 65 00 [email protected] [email protected] Before restoration After restoration Marius by Marcel Pagnol (1931). Directed by Alexander Korda. 2 The restoration of the Marseilles trilogy begins with Marius "Towards 1925, when I felt as if I was exiled in Paris, I realised that I loved Marseilles and I wanted to express this love by writing a Marseilles play. -

Graham Greene's Work in the Time of the Cold

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglistiky Bakalářská práce Graham Greene’s Work in the Time of the Cold War Vypracoval: František Linduška Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph.D. České Budějovice 2017 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že svoji bakalářskou práci jsem vypracoval samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě – v úpravě vzniklé vypuštěním vyznačených částí archivovaných pedagogickou fakultou elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. 11.7.2017 Podpis Poděkování Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat vedoucí této bakalářské práce PhDr. Alici Sukdolové, Ph.D. za odborné vedení, za pomoc a rady při zpracování všech údajů a v neposlední řadě i za trpělivost a ochotu, kterou mi v průběhu psaní této práce věnovala. Abstrakt Tato práce zkoumá vliv politického prostředí na tvorbu anglického prozaika Grahama Greena ve druhé polovině jeho tvůrčího života. Zaměří se na proměnu stylu psaní autora, psychologický a morální vývoj charakterů hlavních hrdinů a na celkovou charakteristiku Greenovy poetiky.