Microfilmed 2002 Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

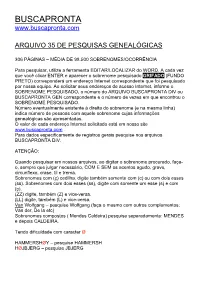

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Tasker H. Bliss and the Creation of the Modern American Army, 1853-1930

TASKER H. BLISS AND THE CREATION OF THE MODERN AMERICAN ARMY, 1853-1930 _________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Thomas R. English December 2014 Examining Committee Members: Richard Immerman, Advisory Chair, Temple University, Department of History Gregory J. W. Urwin, Temple University, Department of History Jay Lockenour, Temple University, Department of History Daniel W. Crofts, External Member,The College of New Jersey, Department of History, Emeritus ii © Copyright 2014 By Thomas R. English All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A commonplace observation among historians describes one or another historical period as a time of “transition” or a particular person as a “transitional figure.” In the history of the United States Army, scholars apply those terms especially to the late- nineteenth century “Old Army.” This categorization has helped create a shelf of biographies of some of the transitional figures of the era. Leonard Wood, John J. Pershing, Robert Lee Bullard, William Harding Carter, Henry Tureman Allen, Nelson Appleton Miles and John McCallister Schofield have all been the subject of excellent scholarly works. Tasker Howard Bliss has remained among the missing in that group, in spite of the important activities that marked his career and the wealth of source materials he left behind. Bliss belongs on that list because, like the others, his career demonstrates the changing nature of the U.S. Army between 1871 and 1917. Bliss served for the most part in administrative positions in the United States and in the American overseas empire. -

Any Victory Not Bathed in Blood: William Rosecrans's Tullahoma

A BGES Civil War Field University Program: Any Victory Not Bathed in Blood: William Rosecrans’s Tullahoma Advance With Jim Ogden June 17–20, 2020; from Murfreesboro, TN “COMPEL A BATTLE ON OUR OWN GROUND?”: William Rosecrans on the objectives of his Tullahoma advance. A “victory not bathed in blood.” A campaign with no major battle. Only a “campaign of maneuver.” You are a real student of the Civil War if you have given serious consideration to this key component of Maj. Gen. William Starke Rosecrans’s command tenure. Sadly, if not entirely overlooked, it usually is only briefly reviewed in histories of the war. Because of the way it did turn out, it is easy to say that it is only a campaign of maneuver, but as originally conceived the Federal army commander intended and expected much more. Henry Halleck’s two “great objects” were still to be achieved. Rosecrans hoped that when he advanced from Murfreesboro, much would be accomplished. In this BGES program we’ll examine what Rosecrans hoped would be a campaign that might include not the but rather his planned “Battle for Chattanooga.” Wednesday, June 17, 2020 6 PM. Gather at our headquarters hotel in Murfreesboro where Jim will introduce you to General Rosecrans, his thinking and combat planning. He is an interesting character whose thinking is both strategic and advanced tactical. He was a man of great capacity and the logic behind this operation, when juxtaposed against the expectations of the national leadership, reveals the depth of Rosecrans’s belief in his ability to deliver decisive results that supported Lincoln’s war objectives. -

Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett

Spring Grove Cemetery, once characterized as blending "the elegance of a park with the pensive beauty of a burial-place," is the final resting- place of forty Cincinnatians who were generals during the Civil War. Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett f the forty Civil War generals who are buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, twenty-three had advanced from no military experience whatsoever to attain the highest rank in the Union Army. This remarkable feat underscores the nature of the Northern army that suppressed the rebellion of the Confed- erate states during the years 1861 to 1865. Initially, it was a force of "inspired volunteers" rather than a standing army in the European tradition. Only seven of these forty leaders were graduates of West Point: Jacob Ammen, Joshua H. Bates, Sidney Burbank, Kenner Garrard, Joseph Hooker, Alexander McCook, and Godfrey Weitzel. Four of these seven —Burbank, Garrard, Mc- Cook, and Weitzel —were in the regular army at the outbreak of the war; the other three volunteered when the war started. Only four of the forty generals had ever been in combat before: William H. Lytle, August Moor, and Joseph Hooker served in the Mexican War, and William H. Baldwin fought under Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Italian civil war. This lack of professional soldiers did not come about by chance. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, its delegates, who possessed a vast knowledge of European history, were determined not to create a legal basis for a standing army. The founding fathers believed that the stand- ing armies belonging to royalty were responsible for the endless bloody wars that plagued Europe. -

Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Schieffler, George David, "Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2426. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2426 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by George David Schieffler The University of the South Bachelor of Arts in History, 2003 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2005 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Daniel E. Sutherland Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dr. Patrick G. Williams Committee Member Committee Member Abstract “Civil War in the Delta” describes how the American Civil War came to Helena, Arkansas, and its Phillips County environs, and how its people—black and white, male and female, rich and poor, free and enslaved, soldier and civilian—lived that conflict from the spring of 1861 to the summer of 1863, when Union soldiers repelled a Confederate assault on the town. -

The Shadow of Napoleon Upon Lee at Gettysburg

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar The Shadow of Napoleon upon Lee at Gettysburg Charles Teague Every general commanding an army hopes to win the next battle. Some will dream that they might accomplish a decisive victory, and in this Robert E. Lee was no different. By the late spring of 1863 he already had notable successes in battlefield trials. But now, over two years into a devastating war, he was looking to destroy the military force that would again oppose him, thereby assuring an end to the war to the benefit of the Confederate States of America. In the late spring of 1863 he embarked upon an audacious plan that necessitated a huge vulnerability: uncovering the capital city of Richmond. His speculation, which proved prescient, was that the Union army that lay between the two capitals would be directed to pursue and block him as he advanced north Robert E. Lee, 1865 (LOC) of the Potomac River. He would thereby draw it out of entrenched defensive positions held along the Rappahannock River and into the open, stretched out by marching. He expected that force to risk a battle against his Army of Northern Virginia, one that could bring a Federal defeat such that the cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Washington might succumb, morale in the North to continue the war would plummet, and the South could achieve its true independence. One of Lee’s major generals would later explain that Lee told him in the march to battle of his goal to destroy the Union army. -

Callaway County, Missouri During the Civil War a Thesis Presented to the Department of Humanities

THE KINGDOM OF CALLAWAY: CALLAWAY COUNTY, MISSOURI DURING THE CIVIL WAR A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By ANDREW M. SAEGER NORTHWEST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY MARYVILLE, MISSOURI APRIL 2013 Kingdom of Callaway 1 Running Head: KINGDOM OF CALLAWAY The Kingdom of Callaway: Callaway County, Missouri During the Civil War Andrew M. Saeger Northwest Missouri State University THESIS APPROVED Thesis Advisor Date Dean of Graduate School Date Kingdom of Callaway 2 Abstract During the American Civil War, Callaway County, Missouri had strong sympathies for the Confederate States of America. As a rebellious region, Union forces occupied the county for much of the war, so local secessionists either stayed silent or faced arrest. After a tense, nonviolent interaction between a Federal regiment and a group of armed citizens from Callaway, a story grew about a Kingdom of Callaway. The legend of the Kingdom of Callaway is merely one characteristic of the curious history that makes Callaway County during the Civil War an intriguing study. Kingdom of Callaway 3 Introduction When Missouri chose not to secede from the United States at the beginning of the American Civil War, Callaway County chose its own path. The local Callawegians seceded from the state of Missouri and fashioned themselves into an independent nation they called the Kingdom of Callaway. Or so goes the popular legend. This makes a fascinating story, but Callaway County never seceded and never tried to form a sovereign kingdom. Although it is not as fantastic as some stories, the Civil War experience of Callaway County is a remarkable microcosm in the story of a sharply divided border state. -

Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves Ben Parten Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2017 "Somewhere Toward Freedom:" Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves Ben Parten Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Parten, Ben, ""Somewhere Toward Freedom:" Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves" (2017). All Theses. 2665. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2665 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SOMEWHERE TOWARD FREEDOM:” SHERMAN’S MARCH AND GEORGIA’S REFUGEE SLAVES A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts History by Ben Parten May 2017 Accepted by: Dr. Vernon Burton, Committee Chair Dr. Lee Wilson Dr. Rod Andrew ABSTRACT When General William T. Sherman’s army marched through Georgia during the American Civil War, it did not travel alone. As many as 17,000 refugee slaves followed his army to the coast; as many, if not more, fled to the army but decided to stay on their plantations rather than march on. This study seeks to understand Sherman’s march from their point of view. It argues that through their refugee experiences, Georgia’s refugee slaves transformed the march into one for their own freedom and citizenship. Such a transformation would not be easy. Not only did the refugees have to brave the physical challenges of life on the march, they had to also exist within a war waged by white men. -

The Lincoln- Mcclellan Relationship in Myth and Memory

The Lincoln- McClellan Relationship in Myth and Memory MARK GRIMSLEY Like many Civil War historians, I have for many years accepted invita- tions to address the general public. I have nearly always tried to offer fresh perspectives, and these have generally been well received. But almost invariably the Q and A or personal exchanges reveal an affec- tion for familiar stories or questions. (Prominent among them is the query “What if Stonewall Jackson had been present at Gettysburg?”) For a long time I harbored a private condescension about this affec- tion, coupled with complete incuriosity about what its significance might be. But eventually I came to believe that I was missing some- thing important: that these familiar stories, endlessly retold in nearly the same ways, were expressions of a mythic view of the Civil War, what the amateur historian Otto Eisenschiml memorably labeled “the American Iliad.”1 For Eisenschiml “the American Iliad” was merely a clever title for a compendium of eyewitness accounts of the conflict, but I take the term seriously. In Homer’s Iliad the anger of Achilles, the perfidy of Agamemnon, the doomed gallantry of Hector—and the relationships between them—have enormous, uncontested, unchanging, and almost primal symbolic meaning. So too do certain figures in the American Iliad. Prominent among these are the butcher Grant, the Christ-like Lee, and the rage- filled Sherman. I believe that the traditional Civil War narrative functions as a national myth of central importance to our understanding of ourselves as Americans. And like the classic mythologies of old, it contains timeless wisdom about what it means to be a human being. -

Collection SC 0084 W. Roger Smith Civil War Research Collection 1862

Collection SC 0084 W. Roger Smith Civil War Research Collection 1862 Table of Contents User Information Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Container List Processed by Emily Hershman 27 June 2011 Thomas Balch Library 208 W. Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 USER INFORMATION VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 2 folders COLLECTION DATES: 1862 PROVENANCE: W. Roger Smith, Midland, TX. ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: Collection open for research USE RESTRICTIONS: No physical characteristics affect use of this material. REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from Thomas Balch Library. CITE AS: W. Roger Smith Civil War Research Collection, 1862 (SC 0084), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. ALTERNATE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS: None RELATED HOLDINGS: None ACCESSION NUMBERS: 1995.0046 NOTES: Formerly filed in Thomas Balch Library Vertical Files 2 HISTORICAL SKETCH From its organization in July 1861, the Army of the Potomac remained the primary Union military force in the East, confronting General Robert E. Lee’s (1807-1870) Army of Northern Virginia in a series of battles and skirmishes. In the early years of the Civil War, however, the Army of the Potomac suffered defeats at the Battle of the First Bull Run in 1861, the Peninsula Campaign and the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862, as well as the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. Historians attribute its initial lack of victories to poor leadership from a succession of indecisive generals: Irvin McDowell (1818-1885), George McClellan (1826-1885), Ambrose Burnside (1824-1881), and Joseph Hooker (1814-1879). When General George Meade (1815-1872) took command of the Army of the Potomac in June 1863, he was successful in pushing the Army of Northern Virginia out of Pennsylvania following the Battle of Gettysburg. -

Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through His Life at Arlington House

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2020 The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House Cecilia Paquette University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Paquette, Cecilia, "The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House" (2020). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1393. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE THAT BUILT LEE Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House BY CECILIA PAQUETTE BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2017 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History September, 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2020 Cecilia Paquette ii This thesis was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in History by: Thesis Director, Jason Sokol, Associate Professor, History Jessica Lepler, Associate Professor, History Kimberly Alexander, Lecturer, History On August 14, 2020 Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. !iii to Joseph, for being my home !iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisory committee at the University of New Hampshire. -

John Brown's Raid: Park Videopack for Home and Classroom. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 957 SO 031 281 TITLE John Brown's Raid: Park VideoPack for Home and Classroom. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-912627-38-7 PUB DATE 1991-00-00 NOTE 114p.; Accompanying video not available from EDRS. AVAILABLE FROM Harpers Ferry Historical Association, Inc., P.O. Box 197, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425 ($24.95). Tel: 304-535-6881. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Teacher (052)-- Historical Materials (060)-- Non-Print Media (100) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); Curriculum Enrichment; Heritage Education; Historic Sites; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; *Slavery; Social Studies; Thematic Approach; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Brown (John); United States (South); West Virginia; *West Virginia (Harpers Ferry) ABSTRACT This video pack is intended for parents, teachers, librarians, students, and travelers interested in learning about national parklands and how they relate to the nation's natural and cultural heritage. The video pack includes a VHS video cassette on Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, an illustrated handbook with historical information on Harpers Ferry, and a study guide linking these materials. The video in this pack, "To Do Battle in the Land," documents John Brown's 1859 attempt to end slavery in the South by attacking the United States Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). The 27-minute video sets the scene for the raid that intensified national debate over the slavery issue. The accompanying handbook, "John Brown's Raid," gives a detailed account of the insurrection and subsequent trial that electrified the nation and brought it closer to civil war.