ONLINE MUSIC DISTRIBUTION the Faculty of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

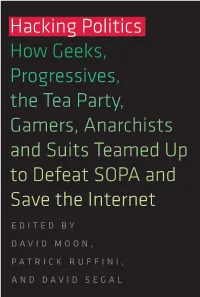

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet EDITED BY DAVID MOON, PATRICK RUFFINI, AND DAVID SEGAL Hacking Politics THE ULTIMATE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE INTERNET KNOCK-DOWN BATTLE! Hacking Politics From Aaron to Zoe—they’re here, detailing what the SOPA/PIPA battle was like, sharing their insights, advice, and personal observations. Hacking How Geeks, Politics includes original contributions by Aaron Swartz, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Ron Paul, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian, Cory Doctorow, Kim Dotcom and many other technologists, activists, and artists. Progressives, Hacking Politics is the most comprehensive work to date about the SOPA protests and the glorious defeat of that legislation. Here are reflections on why and how the effort worked, but also a blow-by-blow the Tea Party, account of the battle against Washington, Hollywood, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that led to the demise of SOPA and PIPA. Gamers, Anarchists DAVID MOON, former COO of the election reform group FairVote, is an attorney and program director for the million-member progressive Internet organization Demand Progress. Moon, Moon, and Suits Teamed Up PATRICK RUFFINI is founder and president at Engage, a leading digital firm in Washington, D.C. During the SOPA fight, he founded “Don’t Censor the to Defeat SOPA and Net” to defeat governmental threats to Internet freedom. Prior to starting Engage, Ruffini led digital campaigns for the Republican Party. Ruffini, Save the Internet DAVID SEGAL, executive director of Demand Progress, is a former Rhode Island state representative. -

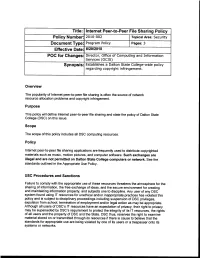

Internet Peer-To-Peer File Sharing Policy Effective Date 8T20t2010

Title: Internet Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Policy Policy Number 2010-002 TopicalArea: Security Document Type Program Policy Pages: 3 Effective Date 8t20t2010 POC for Changes Director, Office of Computing and Information Services (OCIS) Synopsis Establishes a Dalton State College-wide policy regarding copyright infringement. Overview The popularity of Internet peer-to-peer file sharing is often the source of network resource allocation problems and copyright infringement. Purpose This policy will define Internet peer-to-peer file sharing and state the policy of Dalton State College (DSC) on this issue. Scope The scope of this policy includes all DSC computing resources. Policy Internet peer-to-peer file sharing applications are frequently used to distribute copyrighted materials such as music, motion pictures, and computer software. Such exchanges are illegal and are not permifted on Dalton State Gollege computers or network. See the standards outlined in the Appropriate Use Policy. DSG Procedures and Sanctions Failure to comply with the appropriate use of these resources threatens the atmosphere for the sharing of information, the free exchange of ideas, and the secure environment for creating and maintaining information property, and subjects one to discipline. Any user of any DSC system found using lT resources for unethical and/or inappropriate practices has violated this policy and is subject to disciplinary proceedings including suspension of DSC privileges, expulsion from school, termination of employment and/or legal action as may be appropriate. Although all users of DSC's lT resources have an expectation of privacy, their right to privacy may be superseded by DSC's requirement to protect the integrity of its lT resources, the rights of all users and the property of DSC and the State. -

Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere Shayne Pepper Northeastern Illinois University, [email protected]

Northeastern Illinois University NEIU Digital Commons Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Communication, Media and Theatre Publications 2010 Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere Shayne Pepper Northeastern Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://neiudc.neiu.edu/cmt-pub Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Pepper, Shayne, "Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere" (2010). Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Publications. 3. https://neiudc.neiu.edu/cmt-pub/3 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication, Media and Theatre at NEIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication, Media and Theatre Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of NEIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected],[email protected]. Joanna Newsom Covers in the Blogosphere Shayne Pepper “This is an old song. These are old blues. And this is not my song, but it’s mine to use.” -- “Sadie” Joanna Newsom’s 2004 album, The Milk-Eyed Mender, was released at a time when music blogs were reaching new levels of popularity within certain sections of music and online communities. During this time, songs from nearly every high profile indie rock release seemed to find their way onto music blogs (often, to the chagrin of the music industry, far before slated release dates). Newsom’s songs were no exception – she was often something of a hot topic on blogs like Stereogum, My Old Kentucky Blog, Brooklyn Vegan, Gorilla vs. -

Page Ranking Advogato Free and Open So

Name Description/ Registered Registration Global Alexa[1] Focus users Page ranking Advogato Free and open 13,575[2] Open 118,513[3] source software developers Amie Street Music Open 29,808[4] ANobii Books Open 14,345[5] aSmallWorld European jet set 270,000[6] Invite-only 9,306[7] and social elite Athlinks Running, 54,270[8] Open 94,171[9] Swimming, Cycling, Mountain Biking, Triathlon, and Adventure Racing Avatars Online games. Open United Badoo General, Popular 13,000,000[10] Open to people 18 213[11] in Europe and older Bahu General, Popular 1,000,000[12] Open to people 13 2,946[13] in France, Belgium and older and Europe Bebo General. 40,000,000[14] Open to people 13 108[15] and older Biip Norwegian Requires Community. Norwegian phone number. BlackPlanet African-Americans 20,000,000[16] Open 901[17] Boomj.com Boomers and Open to age 30 15,318[18] Generation Jones and up Broadcaster. Video sharing and 322,715[19] Open com webcam chat Buzznet Music and pop- 10,000,000[20] Open 498[21] culture CafeMom Mothers 1,250,000[22] Open to moms and 3,090[23] moms-to-be Cake Investing Open Financial Care2 Green living and 9,961,947[24] Open social activism Classmates.c School, college, 50,000,000[25] Open 923[26] om work and the military Cloob General. Popular Open in Iran. College College students. requires an e-mail Tonight address with an ".edu" ending CouchSurfin Worldwide network 871,049[27] Open g for making connections between travelers and the local communities they visit. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Led Zeppelin R.E.M. Queen Feist the Cure Coldplay the Beatles The

Jay-Z and Linkin Park System of a Down Guano Apes Godsmack 30 Seconds to Mars My Chemical Romance From First to Last Disturbed Chevelle Ra Fall Out Boy Three Days Grace Sick Puppies Clawfinger 10 Years Seether Breaking Benjamin Hoobastank Lostprophets Funeral for a Friend Staind Trapt Clutch Papa Roach Sevendust Eddie Vedder Limp Bizkit Primus Gavin Rossdale Chris Cornell Soundgarden Blind Melon Linkin Park P.O.D. Thousand Foot Krutch The Afters Casting Crowns The Offspring Serj Tankian Steven Curtis Chapman Michael W. Smith Rage Against the Machine Evanescence Deftones Hawk Nelson Rebecca St. James Faith No More Skunk Anansie In Flames As I Lay Dying Bullet for My Valentine Incubus The Mars Volta Theory of a Deadman Hypocrisy Mr. Bungle The Dillinger Escape Plan Meshuggah Dark Tranquillity Opeth Red Hot Chili Peppers Ohio Players Beastie Boys Cypress Hill Dr. Dre The Haunted Bad Brains Dead Kennedys The Exploited Eminem Pearl Jam Minor Threat Snoop Dogg Makaveli Ja Rule Tool Porcupine Tree Riverside Satyricon Ulver Burzum Darkthrone Monty Python Foo Fighters Tenacious D Flight of the Conchords Amon Amarth Audioslave Raffi Dimmu Borgir Immortal Nickelback Puddle of Mudd Bloodhound Gang Emperor Gamma Ray Demons & Wizards Apocalyptica Velvet Revolver Manowar Slayer Megadeth Avantasia Metallica Paradise Lost Dream Theater Temple of the Dog Nightwish Cradle of Filth Edguy Ayreon Trans-Siberian Orchestra After Forever Edenbridge The Cramps Napalm Death Epica Kamelot Firewind At Vance Misfits Within Temptation The Gathering Danzig Sepultura Kreator -

New Building to Integrate Biology, Engineering

Today: Cloudy THE TUFTS High 50 Low 36 Tufts’ Student Tomorrow: Newspaper AM Rain Since 1980 High 45 Low 32 VOLU M E LV, NU M BER 38 DAILY FRIDAY , MARCH 14, 2008 Renovations will New building to integrate biology, engineering improve bathrooms BY NI N A FORD The biology department has been We don’t have a single open laboratory.” Daily Editorial Board battling with space constraints for over Some professors have even had to in Metcalf and West a decade, according to Juliet Fuhrman, sacrifice their research rooms. “Right Tufts plans to completely rebuild all of Tufts will build an integrated biology the department chair. “I got here in now many of our senior faculty have the common-area bathrooms in West and and engineering building in an attempt 1991, and even then we knew that the actually given up their laboratory space Metcalf Halls this summer as part of a larger to facilitate greater multidisciplinary biology program was being squeezed,” so that younger faculty members can program of campus renovations. collaboration and remedy the current she said. have a space where they can get their The renovations will begin directly after space deficiency in both departments. The lack of classroom and research research started,” Fuhrman said. commencement, when there will be a The project is still in its planning stag- space for students and professors in Provost Jamshed Bharucha, a major “demolition of all the common-area toilets,” es and is not expected to begin soon. both disciplines has become more pro- proponent of the new building, agreed. -

2012 April 21

SPECIAL ISSUE MUSIC • • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES STREET DATE: APRIL 21 ORDERS DUE: MAR 21 SPECIAL ISSUE ada-music.com 2012 RECORD STORE DAY-RELATED CATALOG Artist Title Label Fmt UPC List Order ST. VINCENT KROKODIL 4AD S 652637321173 $5.99 ST. VINCENT ACTOR 4AD CD 652637291926 $14.98 ST. VINCENT ACTOR 4AD A 652637291919 $15.98 BEGGARS ST. VINCENT MARRY ME BANQUET CD 607618025427 $14.98 BEGGARS ST. VINCENT MARRY ME BANQUET A 607618025410 $14.98 ST. VINCENT STRANGE MERCY 4AD CD 652637312324 $14.98 ST. VINCENT STRANGE MERCY 4AD A 652637312317 $17.98 TINARIWEN TASSILI ANTI/EPITAPH A 045778714810 $24.98 TINARIWEN TASSILI ANTI/EPITAPH CD 045778714827 $15.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE DELUXE VINYL BOX ANTI/EPITAPH A 045778717415 $59.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE ANTI/EPITAPH CD 045778715626 $17.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE ANTI/EPITAPH A 045778715619 $27.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE (DELUXE VERSION) ANTI/EPITAPH CD 045778717422 $21.98 GOLDEN SMOG STAY GOLDEN, SMOG: THE BEST OF RHINO RYKO CD 081227991456 $16.98 GOLDEN SMOG WEIRD TALES RHINO RYKO CD 014431044625 $11.98 GOLDEN SMOG DOWN BY THE OLD MAINSTREAM RYKODISC A 014431032516 $18.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE TRANSVERSE TEMPORAL GYRUS DOMINO MS 801390032417 $15.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE FALL BE KIND EP DOMINO A 801390024610 $11.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE FALL BE KIND EP DOMINO CD 801390024627 $9.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE MERRIWEATHER POST PAVILION DOMINO A 801390021916 $23.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE MERRIWEATHER POST PAVILION DOMINO CD 801390021923 $15.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE STRAWBERRY JAM -

An Empirical Study of Observational Learning

An Empirical Study of Observational Learning Peter W. Newberry∗ The Pennsylvania State University June 17, 2013 Abstract This paper is an empirical examination of observational learning. Using data from an online market for music, I find that learning is a valuable tool for the producers of high quality products and for consumers, but not necessarily for the online platform. I also study the role of pric- ing as a friction to the learning process by comparing outcomes under a demand-based pricing scheme to the counterfactual outcomes under a fixed price. I find that a price of 99 cents per song (the traditional price in the industry) hampers learning by reducing the incentive to experiment. Keywords: Observational Learning, Online Markets, Recorded Music, Search Goods, Demand- Based Pricing JEL Codes: L15, L82, M31, D83 ∗Contact information: [email protected]. I am grateful to J-F Houde, Ken Hendricks and Alan Sorensen for their support and advice on this project. I also am thankful for comments and suggestions from Paul Grieco, Dan Quint, Chris Adams, Mark Roberts, Russ Cooper, Amit Gandhi and numerous other seminar and conference participants. All remaining errors are my own. 1 Introduction When a consumer is uncertain about a new product, she may rely on information provided by her peers as a signal of the unknown quality. Opportunities for this social learning exist in many markets today, with product reviews and/or popularity rankings being especially prevalent. The latter is an example of observational learning: learning from observing the purchase decisions of your peers. In this paper, I estimate the effect of observational learning on three market-level outcomes: the probability of success for a high quality product (i.e., discovery), the expected consumer welfare, and the expected revenue. -

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay Radiohead Korn Green Day Nickelback Placebo Katy Perry Kumm Red Hot Chili Peppers My Chemical Romance Eels REM Vita de Vie Nine Inch Nails Good Charlotte Goo Goo Dolls Pennywise Barenaked Ladies Three Days Grace Alkaline Trio Alanis Morissette Guano Apes James Blunt Travka Reamonn Godsmack Fear Factory Garbage Kings Of Leon Muse Gandul Matei Sister Hazel Incubus White Zombie Papa Roach System of a Down AB4 Oasis Seether Smashing Pumpkins Alien Ant Farm The Killers Ill Nino Prodigy Taking Back Sunday Alice in Chains Kutless Timpuri Noi Taproot Snow Patrol Nonpoint Dashboard Confessional The Cure The Cranberries Stereophonics Blink 182 Phish Blur Rage Against the Machine Gorillaz Pulp Bowling For Soup Citizen Cope Manic Street Preachers Luna Amara Nirvana The Verve Breaking Benjamin Chevelle Modest Mouse Jeff Buckley Beck Arctic Monkeys Bloodhound Gang Sevendust Coma Lostprophets Keane Blue October 30 Seconds to Mars Suede Collective Soul Kill Hannah Foo Fighters The Cult Feeder Veruca Salt Skunk Anansie 3 Doors Down Deftones Sugar Ray Counting Crows Mushroomhead Electric Six Filter Lynyrd Skynyrd Biffy Clyro Death Cab For Cutie Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds The White Stripes James Morrison Texas Crazy Town Mudvayne Placebo Crash Test Dummies Poets Of The Fall Jason Mraz Linkin Park Sum 41 Grimus Guster A Perfect Circle Tool The Strokes Flyleaf Chris Cornell Smile Empty Soul Audioslave Nirvana Gogol Bordello Bloc Party Thousand Foot Krutch Brand New Razorlight Puddle Of Mudd Sonic Youth -

Song Title Artist Genre

Song Title Artist Genre - General The A Team Ed Sheeran Pop A-Punk Vampire Weekend Rock A-Team TV Theme Songs Oldies A-YO Lady Gaga Pop A.D.I./Horror of it All Anthrax Hard Rock & Metal A** Back Home (feat. Neon Hitch) (Clean)Gym Class Heroes Rock Abba Megamix Abba Pop ABC Jackson 5 Oldies ABC (Extended Club Mix) Jackson 5 Pop Abigail King Diamond Hard Rock & Metal Abilene Bobby Bare Slow Country Abilene George Hamilton Iv Oldies About A Girl The Academy Is... Punk Rock About A Girl Nirvana Classic Rock About the Romance Inner Circle Reggae About Us Brooke Hogan & Paul Wall Hip Hop/Rap About You Zoe Girl Christian Above All Michael W. Smith Christian Above the Clouds Amber Techno Above the Clouds Lifescapes Classical Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Classic Rock Abracadabra Sugar Ray Rock Abraham, Martin, And John Dion Oldies Abrazame Luis Miguel Latin Abriendo Puertas Gloria Estefan Latin Absolutely ( Story Of A Girl ) Nine Days Rock AC-DC Hokey Pokey Jim Bruer Clip Academy Flight Song The Transplants Rock Acapulco Nights G.B. Leighton Rock Accident's Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Rock Accidents Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accordian Man Waltz Frankie Yankovic Polka Accordian Polka Lawrence Welk Polka According To You Orianthi Rock Ace of spades Motorhead Classic Rock Aces High Iron Maiden Classic Rock Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Country Acid Bill Hicks Clip Acid trip Rob Zombie Hard Rock & Metal Across The Nation Union Underground Hard Rock & Metal Across The Universe Beatles -

Flobots Rise Mp3 Download

Flobots rise mp3 download click here to download Flobots Rise Lyrics. Free download Flobots Rise Lyrics mp3 for free. Flobots-Rise with lyrics. Duration: Size: MB. Play Download. Flobots - Rise. Duration: Size: MB. Play Download. Flobots- Rise (+ Lyrics). Flobots- Rise (+ Lyrics). Duration: Size: MB. Play Download. Flobots Rise with lyrics. Download flobots rise Mp3 Download. Rise - www.doorway.ru Flobots Rise Free Mp3 Download. Play and download Flobots Rise mp3 songs from multiple sources at www.doorway.ru There Is A War Going On For You Mind. Duration: Size: MB. Play Download. Star Star Nova. Duration: Size: MB. Play Download. Episode 93 ~ Surfing Seizure, Epic Ambient and Africa-Inspired Hardstyle. Duration: Size: MB. Play Download. Recent Search. Catch My Breath Lyrics Kelly. Free Mp3 Flobots Rise Concert Download, Lyric Flobots Rise Concert Chord Guitar, Free Ringtone Flobots Rise Concert Download, and Get Flobots Rise Concert Hiqh Qualtiy audio from Amazon, Spotify, Deezer, Itunes, Google Play, Youtube, Soundcloud and More. Free Mp3 Flobots Rise Mix Download, Lyric Flobots Rise Mix Chord Guitar, Free Ringtone Flobots Rise Mix Download, and Get Flobots Rise Mix Hiqh Qualtiy audio from Amazon, Spotify, Deezer, Itunes, Google Play, Youtube, Soundcloud and More. So much pain we. Dont know how to be but angry. Feel infected like weve got gangrene. Please don't let anybody try to change me. Me Just me. In the middle of a sea full of faces. Full of faces. Some laugh some salivate. Whats in your alleyway. Recycling bins or bullet cases. Its not equal. Its not fair. Were different people. Buy Rise (Album Version): Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - www.doorway.ru Buy Fight With Tools: Read 96 Digital Music Reviews - www.doorway.ru The Kids Aren't www.doorway.ru3.