JAEPL, Vol. 17, Winter 2011-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Irish Mail on Sunday

AUGUST 30 • 2015 The Irish Mail on Sunday XPOSE presenter Lise Cannon ie Italy bound next week for her ■wedding. The TV3 presenter is to marry Autism group for children her rugby beau Richard Realty in style next Saturday. Glenda Gilson has said that she will be heading out for the wedding. Karen Koster is also on the gue3t Hat. Liaa will now moves to help over-18s be honeymooning in Mauritius. THE children's autism mencing services for this services supported by Keith By N ia m h G riffin group.’ Duffy is expanding into adult HEALTH CORRESPONDENT The charity is based in EXPECT fierce he goes ’meo w ’ during GORGEOUS care in response to the crisis Westmeath and will offer adult rivalry on the new her comments, which George w a sn ’t in services. now in Wicklow, which puts services on a limited basis at ■X Factor - and th a t’s then have to be cut. ’He ■taking chances, of In spite of new funding last huge tune and financial first across the Meath and just between the then copies what she the commercial year, families of teenagers tur pressure on the family. The Kildare regions. A HSE spoke judges. It seems said and he gets the New chin kind anyway, when ning 18 and needing to move dilemma followed a break swoman said: ‘I can confirm Simon Cowell is comment,’ says a mole. launching his own from special schools to adult down in planning between the that the HSE are in talks with Dolores settles getting catty with ‘When a g ir l’s" on stage tequila, Casamigos, services are still in limbo. -

Barney Rock Guest Speaker at President's Charity Lunch

The Property Professional QUARTER 1 2020 Barney Rock Guest Speaker at President’s Charity Lunch THE PROPERTY PROFESSIONAL SPACEFORMY DOGTORUN AROUNDDOT IE Whatever makes it your home. My_Home_A4.indd 1 06/11/2019 13:57 IPAV NEWS | Quarter 1 2020 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO Dear Member A very Happy New Year to all members and welcome to the Q1 2020 edition of the Property Professional. The New Year has already got off to a very busy start for IPAV and we have a full programme of activities lined up which are all aimed in helping members to offer an even better professional service to clients. We have now in excess of 1300 members which is a remarkable achievement for the institute. All licensed auctioneers and estate agents are actively encouraged to apply for membership of IPAV and can be assured there will be major benefits accruing from it. This issue is packed with relevant articles for IPAV members along with reports and photographs from recent events, notably our very successful President’s Charity Lunch which was held in the Westbury Hotel on 6 December for a very worthy charity ‘Cycle Against Suicide’. Many members from Cork and the South of Ireland tell me they would love to attend the President’s Lunch but Dublin Football Legend Barney Rock with Dublin is too far to travel, so this year on the 11th December we will be hosting a second President’s IPAV President David McDonnell at the Lunch in the Imperial Hotel, South Mall, Cork. I am delighted with the support I have received from President’s Charity Lunch. -

Spring 2009 MMDDII News Update Muscular Dystrophy Ireland, 71/72 North Brunswick Street, Dublin 7

MDI Newsletter - Issue 41 = Spring 2009 MMDDII News Update Muscular Dystrophy Ireland, 71/72 North Brunswick Street, Dublin 7. ! em Tel: (01) 8721501 Fax: (01) 8724482 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mdi.ie h t rt po p h] u h it s it le e s e up K u o to Pictured at a Photo shoot to t C & 4 le K a 0 ap n 4 ow & o [U 0 n S n launch MDI’s 2009 Awareness - a e 04 io // s it 4 at p: u n r 0 s tt ou l n h ed U v il se : Campaign are Fair City stars t a e - at or r F 'N r p o s O e ne p f rd b li u a an m n Sandra Curran (Una) & Alan s te w l u o y A A n e e o d ot h V w & an v (Keith) T o n r / O’Neill (Keith) with 5 year old N ra rd o .ie V ur o 7 e T C w 0 in e a e 3 az Caoimhe Boers from Wexford h r th 53 g Caoimhe Boers from Wexford T d t r a an x e m S te b w t s um o u n vn J e .t th w w w ffoorr rrlleeyy a HHaa iinn a Tickets available online WW at www..mdi..ie or call €€55 Amy at (01) 8721501 yy ll e 12 onn pag o See DI , M EO h y C wit one ck) Mo eri im.” Joe Lim Sw nts rom tre ese er f Me ) pr mb lion 0 ntre Me Mil ,00 (Ce DI a “ €50 inn y (M rom ise Qu tter ds f Ra ore ren Sla cee rs M Dar son pro me ch - 1 Ja the wim ear ge 1 ft) & S Res Pa (le for on MDI Newsletter - Issue 41 = Spring 2009 Research News MDI – Funded Researcher Makes the News Prof. -

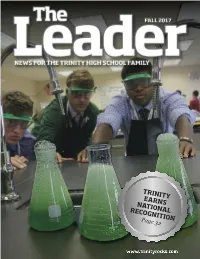

Trinity Earns National Recognition

TRINITY EARNS NATIONAL RECOGNITION Page 32 TRINITY HIGH SCHOOL BE GREA 2 IN THIS ISSUE President’s Notebook................................4 Principal’s Corne r.....................................6 The Spiritual Sid e .....................................8 Alumni Board Chai r ................................10 News From Yo u .......................................12 ISSUE In Memoria m ..........................................14 FALL 2017 Rocks In The Medi a ................................18 ON THE COVER: Students engage hands-on learning in the Alumni News...........................................20 new Walsh Family Chemistry Lab. Cover photo by Scott Scinta ’77, Smashgraphix. The Legac y ..............................................24 Campus News..........................................27 TRINITY HIGH SCHOOL ADVANCEMENT Shamrock Sport s ....................................42 DIRECTOR OF ADMISSIONS Mr. James Torra H’12 Upcoming Event s .......................Back Page ADMISSIONS Mr. Bret Saxton ’05 ADMISSIONS ADMINISTRATIVE 18 20 ASSISTANT Mrs. Melanie Hughes DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS & COMMUNICATIONS Mr. Chris Toth ’06 42 ALUMNI RELATIONS ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Mrs. Carrie Joy SOCIAL MEDIA LIAISON Mr. Joe Porter ’78 TRINITY HIGH SCHOOL FOUNDATION PRESIDENT Dr. Robert J. Mullen ’77 VICE PRESIDENT FOR 24 27 DEVELOPMENT Mr. Jim Beckham ’86 DIRECTOR OF THE TRINITY ANNUAL FUND Mr. Brian Monell ’86 ON THE COVER - TRINITY IS RECOGNIZED NATIONALLY BY MOMENTUM MAGAZINE ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF THE ANNUAL FUND Mrs. Michelle Walters H’17 Trinity is proud to be nationally recognized by Momentum , ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Ms. Sandra Camerucci the leading publication in National Catholic Education. Our dedication to being a student-based school, forming men of The Leader is published four times a year for faith and men of character is the at the core of what we do. Trinity High School alumni, students, parents and friends by Trinity High School, Office for School Advancement, Be sure to see page 32 to read the article. -

KT 6-9-2017 .Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2017 THULHIJJA 15, 1438 AH www.kuwaittimes.net KNPC launches Irma strengthens Syrian army S Korea reach key liquefied into ‘extremely’ breaks Islamic W Cup as Syria gas project2 dangerous6 Cat 5 State siege6 book16 play-offs Kuwait and US to hold Min 27º Max 42º first-of-its-kind forum High Tide 00:57 & 11:33 Low Tide Amir makes a historic trip to US amid regional crisis 05:50 & 18:42 32 PAGES NO: 17323 150 FILS WASHINGTON: His Highness the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- News Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah’s current visit to Washington in brief is historic both in the timing and the level of the accompanying delegation, said a Kuwaiti diplomat yes- terday. This visit also comes at a very delicate time due Kuwait denies reports to the challenges and crises in the Arab region, KUWAIT: Kuwait’s Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Khaled Ambassador of Kuwait to Washington Sheikh Salem Al-Jarallah denied reports on Kuwait opening an embassy Abdullah Al-Jaber Al-Sabah said. in Libya. The visit by Ambassador Mubarak Al-Adwani to He pointed out that the visit comes upon an invita- Libya is only to check up on the conditions of the diplomat- tion from US President Donald Trump last February ic mission, Al-Jarallah said in a statement to Al-Jareeda shortly after his inauguration. The ambassador added newspaper published yesterday. He noted that Al-Adwani that His Highness the Amir is accompanied by a high- had met with Libyan Prime Minister Fayez Al-Sarraj in Tripoli caliber official and business delegation. -

Progress Happy Holidays! for Alumni and Friends of Penn State Schuylkill

Winter 2012 An update on institutional progress Happy Holidays! For Alumni and friends of Penn State Schuylkill For PROGRESS We have made substantial progress as a campus community over the past few months. In !" "sue: Page 1-4 It is during this time of year that we celebrate and give thanks. It is a From the Chancellor’s Desk time for reflection, introspection, and appreciation for the events of the Page 5-11 Academic Affairs past year. I humbly offer a special thanks to the entire Penn State Page 12 Ciletti Library, Division of Schuylkill family – our faculty, staff, students, alumni, advisory board Undergraduate Studies, members, and friends; we are grateful for your unwavering Educational Equity Page 13-14 commitment to the advancement of our campus. It is through your Learning Center, Bursar/Finance, collective support that we are known as a leading institution of higher Business Services education in the state of Pennsylvania and beyond. & Physical Plant Page 15 Bookstore/Barnes & Noble, Our campus traces its beginning back to the strong leadership of local Food Service/ID+ Office Page 16 -17 community and business leaders, as well as local legislators who were Information Technology committed to making affordable high quality higher education available Services, Police Services, Continuing Education to the citizens of Schuylkill County and beyond. As part of one of the Page 18-21 best research institutions in the world, this quality experience has now Development, Alumni Relations, been provided at Penn State Schuylkill for nearly 80 years. In fact, Enrollment Services th Page 21-28 Penn State was recently recognized as the 49 best research Student Affairs, Athletics, institution in the world, one of only two universities in the state of Career Services, Community Service, Pennsylvania with such a distinction. -

Wesley Clover Quarterly Update

WESLEY CLOVER QUARTERLY UPDATE AUGUST 2016 Sharing Summer Successes Welcome to another issue of Q, the that is applied, as well as the rich net- Wesley Clover Quarterly Update. work of initial customer and channel As the summer months arrived in the partner contacts that the companies Northern Hemisphere, they brought are exposed to, provides them with a with them a time of both hard work far greater chance of success than they and relaxation. This packed Update would have otherwise. provides you with some of the You will also read how some of the planned. New properties were added noteworthy developments, from the larger companies are continuing to to the portfolio. Outstanding events technology side of the portfolio across lead their industry sectors. This is the were hosted and managed. Customers to the real estate and philanthropic objective of all the companies, large and guests were treated to top-notch activities. and small, regardless of where they services and entertainment. are started. And it creates a dynamic To begin, you will read about a So please read on. I am happy to share ecosystem within which partnering, number of the new technology these Quarterly Updates with you, and technology sharing, joint marketing companies as they gain their initial I hope you continue to enjoy receiving and selling, and other mutually bene- market traction, both domestically and them. internationally. This in no small way is a ficial relationships are enabled. All to Kind Regards, result of the unique investment model help each other continue to grow and Terry Matthews, Chairman that Wesley Clover wraps around these go global fast. -

Yvonne Lowe It Is with Great Sadness We Report the Death of Yvonne Lowe, a Member of Southampton Hospital Radio Who Passed Away Peacefully on Sunday, October 3Rd 2010

FC On Air 132 document:3_COLON-.AIR 12/11/2010 09:47 Page 1 IFC Regional REP DETAILS 132:19 Regional REP DETAILS 127 12/11/2010 09:49 Page 1 Regional Reps details Region Rep AddRess phone e-mAil Regional Dave Lockyer 54 School Lane 0870 321 6005 [email protected] Manager Higham Rochester Kent ME3 7JF Anglia Mike Sarre 0870 765 9601 [email protected] Home Donald McFarlane 0870 765 9602 [email protected] London Ben Hart 0870 765 9603 [email protected] Midlands 0870 765 9604 [email protected] North David Nicholson 0870 765 9605 [email protected] Northern Davey Downes 0870 765 9606 [email protected] Ireland North West David McGealy 0870 765 9607 [email protected] Scotland Jim Simpson 0870 765 9608 [email protected] South Neil Ogden 0870 765 9609 [email protected] South East Dave Abrey 0870 765 9611 [email protected] Wales & West Steve Allen 0870 765 9613 [email protected] Yorkshire Iain Lee 0870 765 9614 [email protected] Please address correspondence to the Regional Reps at: Hospital Broadcasting Association, PO Box 341, Messingham, Scunthorpe DN15 5EG All members of the EC and Regional Reps are volunteers and will respond to any contact as quickly as possible. Please understand however, that work or family commitments mean that availability may not always be immediate and may be limited to evenings and weekends. 01 INTRO 132:01 INTRO 127 12/11/2010 09:52 Page 1 AUTUMN 2010 Issue 132 The Official Journal of the Hi Everyone, Hospital Broadcasting Association A truly golden issue to bring 2010 to a close. -

BOYZONE Til Danmark 4. August

2011-03-24 09:50 CET BOYZONE til Danmark 4. august Eneste koncert i Danmark ved Skovrock i Aalborg BOYZONE, verdens næststørste boyband, og et af de bedst sælgende irske bands overhovedet, giver torsdag d. 4. aug. en exclusiv koncert i Skovdalen i Aalborg. Alle de største danske navne, og mange udenlandske topnavne som bl.a. Johnny Cash, Bonnie Raitt, Willie Nelson, Runrig og Brian Wilson har tidligere stået på Danmarks største faste udendørs scene i Skovdalen. Men torsdag d. 4. aug. er der lagt op til det hidtil største scoop, når BOYZONE som det eneste sted i Danmark giver koncert i Skovdalen som et led i deres stort anlagte "Brother Tour". Turneen følger op på deres album "Brother" fra sidste år, der er en hyldest til det afdøde bandmedlem Stephen Gately, der pludselig døde i oktober 2009. I februar og marts har Boyzone turneret i England og Irland, en tur der bl.a. har fyldt så store steder som "Wembley Arena" og "The O2" i London, og som har givet fantastiske anmeldelser til de 4 medlemmer Ronan Keating, Mikey Graham, Keith Duffy og Shane Lynch og deres stort anlagte shows. Boyzone har siden starten i 1993 skabt utallige hits, bl.a. ikke færre end 6 nummer 1 hits i UK og 9 nr. 1 hits i Irland. Og sætlisten fra koncerterne i London lover særdeles godt. Flere af bandets medlemmer har sideløbende med Boyzone solokarrierer kørende. Med størst succes Ronan Keating, der var vært for Eurovision Song Contest 1998, hvor Boyzone også optrådte. I 2009 vandt han Dansk Melodi Grand Prix med "Believe Again" sunget af Brinck. -

Boyzone Full Album

1 / 2 Boyzone Full Album KOLEKSI LAGU BOYZONE FULL ALBUM NONSTOP MP3 3GP MP4 HD Free Download, KOLEKSI LAGU BOYZONE FULL ALBUM NONSTOP Online Play and .... Boyzone Greatest Hits - The Best Of Boyzone Full Album 2020. Uploader: Beautiful Love Songs; Duration: 1:29:44; Default Size: 126.19 MB; Default Bitrate: 192 .... The Best Of Westlife Westlife Greatest Hits Full Album mp3. ... Piano, Vocal & Guitar by Boyzone in the range of E4-B5 from Sheet Music Direct.. Boyzone Full Album MP3 Download, Video 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3 Boyzone Full Album gratis and free streaming terbaru hanya di Stafaband.. Boyzone's amazing cover version of "Everything I Own" from their new album BZ20. (C) 2013 Warner/Rhino Lyrics: David Gates Performers: Boyzone.. To support music producers, buy Boyzone Greatest Hits - The Best Of Boyzone (full album) and Original tapes in the Nearest Stores and iTunes .... Selena has her first top 10 | Top Latin Albums (see ge 58) since January 2003 ... 2 on the Official Charts Co. albums tally behind Boyzone's “Brother” (see page 59). ... Mass Chain traditional Merchant Go to www.billboard.biz for complete chart ... Music Forever. Music Forever. Subscribe. Boyzone Greatest Hits Full Album - Boyzone Best Songs 2018. Show less Show more .... Wonder World (released November 7, '11) is the group's sophomore album and their first full length album release after their moderately .... Download song Boyzone Greatest Hits || The Best Of Boyzone full album 2020 MP3 you can download it for free at Mp3 Soul. Song details .... Ireland's answer to the Backstreet Boys was one of Europe's most popular boy bands through the late 1990s. -

Brian Molko's

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2017 GOSSIP Hetfield recovers quickly from tumble at Amsterdam gig etallica's James Hetfield took a tumble on stage at not so much. But, we are fine. It hurt my feelings a maybe, record will feature unreleased material including demos, the band's show in Amsterdam on Monday night. a little bit. But I can tell you about it now it's done." The gui- rough mixes, videos and live tracks, including a new ver- MThe 'Seek & Destroy' rocker narrowly avoided a tar god and vocalist then bravely carried on with the rest of sion of 'Disposable Heroes' and a live recording of 'The serious injury after stepping backwards into a hole in the their 18-song set including an encore of 'Blackened', Thing That Should Not Be'. The LP was the band's first stage near to the drum kit at Ziggo Dome. Video footage "Nothing Else Matters' and Enter Sandman'. Metallica are record to go platinum and ended up going 6 x platinum in showed the 54-year-old singer fall down and pause for a currently on the European leg of their 'WorldWired' tour, the US. 'Master Of Puppets' was the last studio release the moment in pain as the band performed 'Now That We're which comes to London's The O2 on October 22 and 24 band recorded with late bass player Cliff Burton, who was Dead'. In the clip shared on YouTube by a fan, James asks and concludes at Birmingham's Genting Arena on October in the band from 1982 until his death in September 1986. -

Baby Joy for Rhys Meyers

1RM Thursday, September 29, 2016 5 BABY JOY FOR RHYS MEYERS............... Over the moon . smitten couple Mara and Jonathan are They are delighted with their baby news loved up and can’t wait for their tot Horizontal hugs . Rhys Meyers embraces Natalie Dormer in The Tudors JONATHAN Rhys Meyers’ EXCLUSIVE by KEN SWEENEY flowers best Hubby, J.” Last state with bloodshot eyes and his break in the UK hit Bend It Like Showbiz Editor month, Jonathan was among those fly open. He later issued a state- Beckham. But he is best known partner is having a baby, who paid their respects at the ment apologising for the “minor for his role as King Henry VIII in we can reveal. funeral of ‘Batman’ Ben Farrell relapse”, telling fans: “Mara and I the Irish-shot series The Tudors. Beautiful Mara Lane is recent times. It was revealed this who died last month after losing are thankful for your support and Jonathan has faced rehab up to week that Mara changed the name his battle against cancer. kindness during this time. six times in the past. He first about 28 weeks pregnant and of her Instagram page — which she The Dublin youngster, five, was “I apologise for having a minor went to the famous Promises facil- the couple are over the moon shared with dog Toca — to ‘Lane diagnosed with an aggressive relapse and hope that people don’t ity in Malibu in May 2005. about the news, the Irish Sun Rhys Meyers’. tumour last Christmas Eve. think too badly of me.” He also faced charges after sev- has learned.