The Response of Brisbane Grammar School and St Paul's School To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study 12

1 REPORT OF CASE STUDY NO. 12 The response of an independent school in Perth to concerns raised about the conduct of a teacher between 1999 and 2009 JUNE 2015 Report of Case Study No. 12 2 ISBN 978-1-925289-26-8 © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 All material presented in this publication is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence (www.creativecommons.org/licenses). For the avoidance of doubt, this means this licence only applies to material as set out in this document. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence (www.creativecommons.org/licenses). Contact us Enquiries regarding the licence and any use of this document are welcome at: Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse GPO Box 5283 Sydney, NSW, 2001 Email: [email protected] Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au 3 Report of Case Study No. 12 The response of an independent school in Perth to concerns raised about the conduct of a teacher between 1999 and 2009 June 2015 COMMISSIONERS Justice Jennifer Coate Commissioner Bob Atkinson AO APM Commissioner Andrew Murray Report of Case Study No. 12 4 Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au 5 Table of contents Preface 1 Executive summary 5 1 Introduction 18 1.1 The school 18 1.2 YJ’s employment at the school 18 1.3 YJ’s convictions -

Annual Report 2012

Board of Trustees Brisbane Grammar School Annual Report 2012 ISSN 1837-8722 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CONSTITUTION, GOALS AND FUNCTIONS ............................................................. 1 2. LOCATION ...................................................................................................................... 4 3. STRUCTURES ................................................................................................................. 5 4. REVIEW OF THE PROGRESS IN ACHIEVING THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES STATUTORY OBLIGATIONS ....................................................................................... 6 5. SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANT OPERATIONS ............................................................ 6 6. REVIEW OF PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING GOALS AND DELIVERING OUTCOMES ................................................................................................................... 16 7. PROPOSED FORWARD OPERATIONS ..................................................................... 19 8. FINANCIAL OPERATIONS AND EFFECTIVENESS ................................................ 20 9. SYSTEMS FOR OBTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT FINANCIAL AND OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE .............................................................................. 21 10. RISK MANAGEMENT .................................................................................................. 22 11. CARERS (RECOGNITION) ACT 2008 ........................................................................ 23 12. PUBLIC SECTOR ETHICS ACT 1994 ........................................................................ -

Answers to Questions on Notice

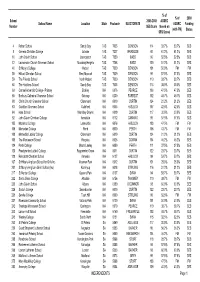

% of % of 2008 School 2005-2008 AGSRC School Name Location State Postcode ELECTORATE AGSRC Funding Number SES Score (based on (with FM) Status SES Score) 4 Fahan School Sandy Bay TAS 7005 DENISON 114 33.7% 33.7% SES 5 Geneva Christian College Latrobe TAS 7307 BRADDON 92 61.2% 61.2% SES 10 John Calvin School Launceston TAS 7250 BASS 99 52.5% 52.5% SES 12 Launceston Church Grammar School Mowbray Heights TAS 7248 BASS 100 51.2% 51.2% SES 40 St Mary's College Hobart TAS 7000 DENISON 101 50.0% FM FM 55 Hilliard Christian School West Moonah TAS 7009 DENISON 95 57.5% 57.5% SES 59 The Friends School North Hobart TAS 7000 DENISON 110 38.7% 38.7% SES 60 The Hutchins School Sandy Bay TAS 7005 DENISON 113 35.0% 35.0% SES 63 Carmel Adventist College - Primary Bickley WA 6076 PEARCE 103 47.5% 47.5% SES 65 Bunbury Cathedral Grammar School Gelorup WA 6230 FORREST 102 48.7% 48.7% SES 68 Christ Church Grammar School Claremont WA 6010 CURTIN 124 21.2% 21.2% SES 83 Guildford Grammar School Guildford WA 6055 HASLUCK 107 42.5% 42.5% SES 84 Hale School Wembley Downs WA 6019 CURTIN 117 30.0% 30.0% SES 92 John Calvin Christian College Armadale WA 6112 CANNING 95 57.5% 57.5% SES 105 Mazenod College Lesmurdie WA 6076 HASLUCK 103 47.5% FM FM 106 Mercedes College Perth WA 6000 PERTH 106 43.7% FM FM 108 Methodist Ladies' College Claremont WA 6010 CURTIN 124 21.2% 21.2% SES 109 The Montessori School Kingsley WA 6026 COWAN 104 46.2% 46.2% SES 124 Perth College Mount Lawley WA 6050 PERTH 111 37.5% 37.5% SES 126 Presbyterian Ladies' College Peppermint Grove WA 6011 CURTIN -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 2019 2 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School Interpretation Requests Brisbane Grammar School is committed to providing accessible services to people from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Please provide any feedback, interpreter requests, copyright requests or suggestions to the Deputy Headmaster – Staff at the undernoted address. Report Availability This report is available for viewing by contacting the Deputy Headmaster – Staff. Brisbane Grammar School Tel (07) 3834 5200 Fax (07) 3834 5202 Email [email protected] Website www.brisbanegrammar.com Online www.brisbanegrammar.com/About/Reporting/ ISSN: 1837-8722 © (Board of Trustees of the Brisbane Grammar School), 2020 Brisbane Grammar School 2019 Annual Report 3 LETTER OF COMPLIANCE 4 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School Table of Contents Letter of Compliance 4 SECTION A GOVERNANCE REPORT 6 About the School 7 Locations 7 Legislative bases 8 Values and ethics 8 Leadership 9 Senior Leadership Team 15 Statutory Requirements 18 Risk management 18 Audit 18 External scrutiny 18 Record keeping 20 SECTION B STRATEGY REPORT 22 From the Chair 23 From the Headmaster 25 Strategic Intent 2018 – 2022 28 2019 In Review 36 Enrolments 36 Academic 39 Student wellbeing 43 Co-Curriculum 46 Staff 49 Advancement and Community Relations 52 Infrastructure 54 Finance 55 SECTION C APPENDICES 57 Open Data 56 Consultancies 58 Overseas travel 58 Financial Statements 59 Glossary 95 Compliance Checklist 99 Brisbane Grammar School 2019 Annual Report 5 Section A Governance Report 6 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School ABOUT THE SCHOOL Locations Spring Hill Campus Brisbane Grammar School provides education programs on five campuses. The main campus of nearly eight hectares is on Gregory Terrace overlooking the Brisbane CBD and is the site for the delivery of the main academic program across Years 5 to 12, as well as the Indoor Sports Centre and boarding house. -

Players and Administrators

Valley District Cricket Club - Players and Administrators Abercrombie Charles Stuart Born:26 October 1878 in Albury, NSW Bat: Bowl: Died:10 September 1954 in Brisbane Son of David John ABERCROMBIE and Grace Marie CANSDELL. Scools: Brisbane Grammar. He was a bank officer, serving with the Bank of Australasia. 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1902 Acton Geoffrey Brockwell Born:26 December 1970 in Bat: Bowl: Died: in 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1991, 1993, 1995 Adams Brett James Born:28 November 1958 in Townsville Bat:RHB Bowl: WK Died: in Brother of RG Adams He represented Queensland Primary Schools in 1970/71; and Queensland Schoolboys in each season from 1974/75 to 1976/77, being captain in the latter two series. He also played grade cricket for Sandgate-Redcliffe. Schools: Clontarf State; St Pauls, Bald Hills. 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1977, 1981, 1982, 1983 Adams Ross George Born:16 November 1955 in Bat: Bowl: RFM Died: in Brother of BJ Adams. Previously played for Northern Suburbs. 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1983 Adamson Charles Young Born:18 April 1875 in Neville’s Cross, Durham, England Bat:RHB Bowl: LSM Died:17 September 1918 in Salonica, Greece Son of Annie LODGE and John ADAMSON. His father and sons CL and JA Adamson all played Minor County cricket for Durham. His brother-in-law to Lewis Vaughan Lodge, who played international football for England He played Minor Country cricket in England for Durham from 1894 to 1914. He was also a rugby player representing Durham and England and touring Australia in 1899. -

Progress in Responding to the Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse

110 Ordinary Session of Synod : Proceedings for 2013 Progress in responding to the Royal Commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse Purpose 1. To inform the Synod of progress in the response of this Diocese to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Sexual Abuse (Commission). Background 2. As at the date of this Report, key matters concerning Royal Commission and its work may be summarised as follows – (a) The Commission has been charged with examining the sexual abuse of children in the context of institutions throughout Australia including churches and their agencies; (b) Other unlawful or improper treatment of children that accompanied child sexual abuse will also be considered by the Commission; (c) The Commission will obtain much of its evidence from the experiences of the individuals involved and will endeavour to ensure there are no obstacles to individuals giving their accounts to the Commission; (d) The Commission will identify where systems have failed to protect children and make recommendations on how to improve laws, policies and practices to prevent and better respond to child sexual abuse in institutions; (e) The Commission will last for at least 3 years (2013 to 2015) and will submit an interim report after 18 months (30 June 2014) to provide early findings and recommendations and to advise if time beyond 3 years is required; (f) The Commission is able to conduct hearings in different parts of the country concurrently and will run both private and public hearings; (g) The Commission is conducting -

Newsletter Week 1 Term 4 Friday 11 October 2019

Newsletter Week 1 Term 4 Friday 11 October 2019 BGS Parent and Son Kokoda Trek | September Holidays In this issue BGSState Newsletter Tennis Tournament| Lead Article Teacher Recognised Duke of Edinburgh Award Headmaster Anthony Micallef Welcome to Term 4 I would like to welcome the BGS community to Term 4. I trust everyone had a satisfying break in preparation for this important term. Throughout the holidays, many students actively prepared for the academic and co-curricular rigours of Term 4. The BGS Track and Field boys prepared for their season with a holiday training camp, while others started pre- season training ahead of Term 1 2020. Students also embarked on their Public Purpose expeditions in Cambodia and Kokoda. Thank you to all staff and students who participated in these activities over the break. Your commitment to the School is appreciated. Working together to achieve a common goal is the essence of being human – it is knowing and feeling that you belong to something special. As we start Term 4, I congratulate the student body for rounding out Term 3 admirably. The boys maintained decorum and behaved respectfully while completing assessments and co-curricular responsibilities to high standards. I also thank the Year 12 cohort for conducting themselves appropriately at the formal. The Class of 2019 was in good spirits and gentlemanly in their manner. I hope the boys have returned from their holiday well rested and ready for a relatively short and constructive term. It is important for every student to see this term as a down payment on further academic success rather than a slide into holidays. -

Evidence Exchange 2016

[email protected] | evidenceforlearning.org.au | @E4Ltweets Evidence Exchange 2016 SPEAKERS Anthony Mackay AM Chief Executive Officer, Centre for Strategic Education (CSE) Anthony Mackay AM is CEO, Centre for Strategic Education (CSE) Melbourne, Inaugural Chair, Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), and Inaugural Deputy Chair, Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). Tony is CoChair of the Global Education Leaders Partnership (GELP) and Inaugural Chair of the Innovation Unit Ltd, England. He is Consultant Advisor to OECD/CERI. Tony is a founding member of the Governing Council of the National College for School Leadership in England. Tony is a member of the International Advisory Board for the Centre for International Benchmarking NCEE, Washington DC. Tony is an Honorary Fellow in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Melbourne, a Council Member of Swinburne University of Technology, a Board Director of the Australian Council for Educational Research, the Asia Education Foundation, the Foundation for Young Australians, and Teach for Australia. Cath Apanah Assistant Principal, Montrose Bay High (TAS) Cath is a passionate advocate for public education and is driven to improve both staff and student learning. She is currently the Assistant Principal for Raising the Bar at Montrose Bay High in Hobart, Tasmania where she is responsible for improving literacy outcomes for students. Cath and the Literacy Team have used data to inform a whole school focus on writing through the development and implementation of a Write to Learn program. The program has worked to build the capacity of staff to plan for and deliver targeted teaching strategies. -

Avenues of Honour, Memorial and Other Avenues, Lone Pines – Around Australia and in New Zealand Background

Avenues of Honour, Memorial and other avenues, Lone Pines – around Australia and in New Zealand Background: Avenues of Honour or Honour Avenues (commemorating WW1) Australia, with a population of then just 3 million, had 415,000 citizens mobilised in military service over World War 1. Debates on conscription were divisive, nationally and locally. It lost 60,000 soldiers to WW1 – a ratio of one in five to its population at the time. New Zealand’s 1914 population was 1 million. World War 1 saw 10% of its people, some 103,000 troops and nurses head overseas, many for the first time. Some 18,277 died in World War1 and another 41,317 (65,000: Mike Roche, pers. comm., 17/10/2018) were wounded, a 58% casualty rate. About another 1000 died within 5 years of 1918, from injuries (wiki). This had a huge impact, reshaping the country’s perception of itself and its place in the world (Watters, 2016). AGHS member Sarah Wood (who since 2010 has toured a photographic exhibition of Victoria’s avenues in Melbourne, Ballarat and France) notes that 60,000 Australian servicemen and women did not return. This left lasting scars on what then was a young, united ‘nation’ of states, only since 1901. Mawrey (2014, 33) notes that when what became known as the ‘Great War’ started, it was soon apparent that casualties were on a scale previously unimaginable. By the end of 1914, virtually all the major combatants had suffered greater losses than in all the wars of the previous hundred years put together. -

Grammar School Magazine

Vol. IX. NOVEMBER, 1907. No. 27- BRISANE GRAMMAR SCHOOL MAGAZINE. lrtakrnr: OUTRIDGE PKINTING CO., LTID. .j9 yIEN STREET'. S907. OUTRIDGE PRINTINO 00. Ltd. Priaters, Bookbiders, Statioersn meet Maebleery. ittee e phi. | l Itee. ulin. PtentBoxes. Foldin c c, and are costantly adin. to thea '11 f3i8 QUEEN ST., BRISBANE. NNMiru hWit FHS|m Plan see ftdll Ad wrtiuments. Morrows Limited, WNII I III~lII "__ .. Confectioners IPee S**., @.emes. a •-**'"---. )Biscuit Baker s, lube.. ParNee. eII. k -: >; +- . -sada" s e. ,..BISBANE. Igamee I. e S111.Y0SB ~s b m~ Agst GeVin a. km v el IAs. hobe ahaed - a Branch Fa~corle: Towvilke and Sydney. -~ A. HERGA, tbronaomcer, Ulatcb, ain Clock fUllaer. Chronographs, Repeaters, Perpetual Calendars a Speciality. Chronometers kept Rated. Importer of btandard Harometers and Electric Clocks. Correct Time daily by electric signals from the Observatory, by permission of the surveyor-General. eIII.Uee IWat m .. .. 11 '- V1eens' sa esMe's Sdve, Webes .. Ut 1/-, 48 II-, 14/-t Ladies' OeM Levere WShes .... 1 1/ M8 II/- WAKEFIELD'S BUILDINGS. EDWARD STREFT. 4 .4 dvertiserments. 'Waton, erguson 6eo. f J rters ofo 6 ceha and Sttrionery, Qoa h.t, " a.-----. \'. F. & Co. toc'k all Ei.1ucational \\,rk used in Private, State and (ramnmar Schools and also all iooks used in connection with the Sydney (University Exain;ations and supply them at special prices to pupils. MURRBL &BBEKER 90 QUEEN STREET NEXT IPAIIN ' MI AN I'ACTUL HEiS Ladis' Ha& Cariers lr Home auld Travel. 89o asnd 40/-. NONE BUT THE B11'f ISADDLRY AiD LARNESS f every deulptlion. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

Frank Patrick Henagan a Life Well Lived

No 81 MarcFebruah 20ry 142014 The Magazine of Trinity College, The University of Melbourne Frank Patrick Henagan A life well lived Celebrating 40 years of co-residency Australia Post Publication Number PP 100004938 CONTENTS Vale Frank 02 Founders and Benefactors 07 Resident Student News 08 Education is the Key 10 Lisa and Anna 12 A Word from our Senior Student 15 The Southern Gateway 16 Oak Program 18 Gourlay Professor 19 New Careers Office 20 2 Theological School News 21 Trinity College Choir 22 Reaching Out to Others 23 In Remembrance of the Wooden Wing 24 Alumni and Friends events 26 Thank You to Our Donors 28 Events Update 30 Alumni News 31 Obituaries 32 8 10 JOIN YOUR NETWORK Did you know Trinity has more than 20,000 alumni in over 50 different countries? All former students automatically become members of The Union of the Fleur-de-Lys, the Trinity College Founded in 1872 as the first college of the University of Alumni Association. This global network puts you in touch with Melbourne, Trinity College is a unique tertiary institution lawyers, doctors, engineers, community workers, musicians and that provides a diverse range of rigorous academic programs many more. You can organise an internship, connect with someone for some 1,500 talented students from across Australia and to act as a mentor, or arrange work experience. Trinity’s LinkedIn around the world. group http://linkd.in/trinityunimelb is your global alumni business Trinity College actively contributes to the life of the wider network. You can also keep in touch via Facebook, Twitter, YouTube University and its main campus is set within the University and Flickr.