Triggering the Formation of the Supergiant H II Region NGC 604 In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Had a Great Time on the Trip. We Had Some Representatives from the Vandenberg and Santa Barbara Clubs Along with Us for the Trip

We had a great time on the trip. We had some representatives from the Vandenberg and Santa Barbara clubs along with us for the trip. The most notable thing on the trip up was a stop in La Canada Flintridge to refuel the bus and get a bite to eat. I pulled out my PST Coronado and did a little impromptu public Sun Gazing. The Sun was pretty active with a number of platform prominences as well as the ever-present flame types. A distinct sunspot group in a very disturbed area of the Sun with a bright spot had me wondering if there was a flare in progress (There wasn’t.) The patrons at the tables outside didn’t seem to object to seeing the Sun either. I had a little bit of a scare when we first got up to the gate as a couple of people who were going to meet us there were nowhere to be seen. Fortunately one of them was already on the grounds and the other showed up while we were in the Museum. Relief! As it turned out we all went on the tour of the grounds. Our tour guide Greg gave us a tour starting outside the 60” Dome. He talked about the various Solar Telescopes -the old Snow telescope which was always a non-performer because of the design of the building- too many air currents. He talked about the rivalry over the 60 and 150 ft tower solar instruments (looks like UCLA won this one over USC.) And we got a good look at the 150 ft tower. -

Feb BACK BAY 2019

Feb BACK BAY 2019 The official newsletter of the Back Bay Amateur Astronomers CONTENTS COMING UP Gamma Burst 2 Feb 7 BBAA Meeting Eclipse Collage 3 7:30-9PM TCC, Virginia Beach NSN Article 6 Heart Nebula 7 Feb 8 Silent Sky Club meeting 10 10-11PM Little Theatre of VB Winter DSOs 11 Contact info 16 Feb 8 Cornwatch Photo by Chuck Jagow Canon 60Da, various exposures, iOptron mount with an Orion 80ED Calendar 17 dusk-dawn The best 9 out of 3465 images taken from about 10:00 PM on the 20th Cornland Park through 2:20 AM on the 21st. Unprocessed images (only cropped). Feb 14 Garden Stars 7-8:30PM LOOKING UP! a message from the president Norfolk Botanical Gardens This month’s most talked about astronomy event has to be the total lunar Feb 16 Saturday Sun-day eclipse. The BBAA participated by supporting the Watch Party at the 10AM-1PM Chesapeake Planetarium. Anyone in attendance will tell you it was COLD, but Elizabeth River Park manageable if you wore layers, utilized the planetarium where Dr. Robert Hitt seemed to have the thermostat set to 100 degrees, and drank copious amounts Feb 23 Skywatch of the hot coffee that Kent Blackwell brewed in the back office. 6PM-10PM The event had a huge following on Facebook but with the cold Northwest River Park temperatures, we weren’t sure how many would come out. By Kent’s estimate there were between 100–200 people in attendance. Many club members set up telescopes, as well as a few members of the public too. -

Swift Satellite Images a Galaxy Ablaze with Starbirth 26 February 2008

Swift satellite images a galaxy ablaze with starbirth 26 February 2008 are clearly resolved, even in the crowded nucleus of the galaxy. The image also includes Milky Way foreground stars and much more distant galaxies shining through M33. Young, hot stars are prodigious producers of ultraviolet light, which heat up the surrounding gas clouds to such high temperatures that they radiate brightly in ultraviolet light. The image shows the giant star-forming region NGC 604 as a bright spot to the lower left of the galaxy's nucleus. With a diameter of 1,500 light-years (40 times that of the Orion Nebula), NGC 604 is the largest stellar Image credit: NASA/Swift Science Team/Stefan Immler nursery in the Local Group. "The ultraviolet colors of star clusters tell us their ages and compositions," says Swift team member Combining 39 individual frames taken over 11 Stephen Holland of NASA Goddard. "With Swift's hours of exposure time, NASA astronomers have high spatial resolution, we can zero in on the created this ultraviolet mosaic of the nearby clusters themselves and separate out nearby stars "Triangulum Galaxy." "This is the most detailed and gas clouds. This will enable us to trace the star- ultraviolet image of an entire galaxy ever taken," forming history of the entire galaxy." says Stefan Immler of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. Immler used "The entire galaxy is ablaze with starbirth," adds NASA's Swift satellite to take the images, and he Immler. "Despite M33's small size, it has a much then assembled them into a mosaic that higher star-formation rate than either the Milky Way seamlessly covers the entire galaxy. -

Astronomy and Astrophysics Books in Print, and to Choose Among Them Is a Difficult Task

APPENDIX ONE Degeneracy Degeneracy is a very complex topic but a very important one, especially when discussing the end stages of a star’s life. It is, however, a topic that sends quivers of apprehension down the back of most people. It has to do with quantum mechanics, and that in itself is usually enough for most people to move on, and not learn about it. That said, it is actually quite easy to understand, providing that the information given is basic and not peppered throughout with mathematics. This is the approach I shall take. In most stars, the gas of which they are made up will behave like an ideal gas, that is, one that has a simple relationship among its temperature, pressure, and density. To be specific, the pressure exerted by a gas is directly proportional to its temperature and density. We are all familiar with this. If a gas is compressed, it heats up; likewise, if it expands, it cools down. This also happens inside a star. As the temperature rises, the core regions expand and cool, and so it can be thought of as a safety valve. However, in order for certain reactions to take place inside a star, the core is compressed to very high limits, which allows very high temperatures to be achieved. These high temperatures are necessary in order for, say, helium nuclear reactions to take place. At such high temperatures, the atoms are ionized so that it becomes a soup of atomic nuclei and electrons. Inside stars, especially those whose density is approaching very high values, say, a white dwarf star or the core of a red giant, the electrons that make up the central regions of the star will resist any further compression and themselves set up a powerful pressure.1 This is termed degeneracy, so that in a low-mass red 191 192 Astrophysics is Easy giant star, for instance, the electrons are degenerate, and the core is supported by an electron-degenerate pressure. -

Metal Enrichment of the Neutral Gas of Blue Compact Dwarf Galaxies: the Compelling Case of Pox 36

A&A 494, 915–932 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:200811089 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics Metal enrichment of the neutral gas of blue compact dwarf galaxies: the compelling case of Pox 36 V. Lebouteiller1, D. Kunth2,T.X.Thuan3, and J. M. Désert2 1 Center for Radiophysics and Space Research, Cornell University, Space Sciences Building, Ithaca, NY 14853-6801, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 98bis Boulevard Arago, 75014 Paris, France 3 Astronomy Department, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22903, USA Received 4 October 2008 / Accepted 11 December 2008 ABSTRACT Context. Evidence has grown over the past few years that the neutral phase of blue compact dwarf (BCD) galaxies may be metal- deficient as compared to the ionized gas of their H ii regions. These results have strong implications for our understanding of the chemical evolution of galaxies, and it is essential to strengthen the method, as well as to find possible explanations. Aims. We present the analysis of the interstellar spectrum of Pox 36 with the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE). Pox 36 was selected because of the relatively low foreground gas content that makes it possible to detect absorption-lines weak enough that unseen components should not be saturated. Methods. Interstellar lines of H i,Ni,Oi,Siii,Pii,Ari,andFeii are detected. Column densities are derived directly from the observed line profiles except for H i, whose lines are contaminated by stellar absorption, thus needing the stellar continuum to be removed. We used the TLUSTY models to remove the stellar continuum and isolate the interstellar component. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Far-Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of Star-Forming Regions in Nearby Galaxies: Stellar Populations and Abundance Indicators

Far-Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of Star-Forming Regions in Nearby Galaxies: Stellar Populations and Abundance Indicators 1 William C. Keel Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Alabama, Box 870324, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487; [email protected] Jay B. Holberg Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; [email protected] Patrick M. Treuthardt Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Alabama, Box 870324, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 Received ; accepted Submitted to the Astronomical Journal arXiv:astro-ph/0403499v1 20 Mar 2004 1Based on observations made with the NASA-CNES-CSA Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer. FUSE is operated for NASA by the Johns Hopkins University under NASA contract NAS5-32985. –2– ABSTRACT We present FUSE spectroscopy and supporting data for star-forming regions in nearby galaxies, to examine their massive-star content and explore the use of abundance and population indicators in this spectral range for high-redshift galaxies. New far-ultraviolet spectra are shown for four bright H II regions in M33 (NGC 588, 592, 595, and 604), the H II region NGC 5461 in M101, and the starburst nucleus of NGC 7714, supplemented by the very-low-metallicity galaxy I Zw 18. In each case, we see strong Milky Way absorption systems from H2, but intrinsic absorption within each galaxy is weak or undetectable, perhaps because of the “UV bias” in which reddened stars which lie behind molecular-rich areas are also heavily reddened. We see striking changes in the stellar-wind lines from these populations with metallicity, suggesting that C II, C III, C IV, N II, N III, and P V lines are potential tracers of stellar metallicity in star-forming galaxies. -

Interstellar H2 in M 33 Detected with FUSE

A&A 398, 983–991 (2003) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20021725 & c ESO 2003 Astrophysics ? Interstellar H2 in M 33 detected with FUSE H. Bluhm1,K.S.deBoer1,O.Marggraf1,P.Richter2, and B. P. Wakker3 1 Sternwarte, Universit¨at Bonn, Auf dem H¨ugel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy 3 University of Wisconsin–Madison, 475 N. Charter Street, Madison, WI 53706, USA Received 30 October 2002 / Accepted 18 November 2002 Abstract. Fuse spectra of the four brightest H ii regions in M 33 show absorption by interstellar gas in the Galaxy and in M 33. On three lines of sight molecular hydrogen in M 33 is detected. This is the first measurement of diffuse H2 in absorption in a Local Group galaxy other than the Magellanic Clouds. A quantitative analysis is difficult because of the low signal to noise ratio and the systematic effects produced by having multiple objects in the Fuse aperture. We use the M 33 Fuse data to demonstrate in a more general manner the complexity of interpreting interstellar absorption line spectra towards multi-object background 16 17 2 sources. We derive H column densities of 10 to 10 cm− along 3 sight lines (NGC 588, NGC 592, NGC 595). Because of 2 ≈ the systematic effects, these values most likely represent upper limits and the non-detection of H2 towards NGC 604 does not exclude the existence of significant amounts of molecular gas along this sight line. Key words. galaxies: individual: M 33 – ISM: abundances – ISM: molecules – ultraviolet: ISM 1. -

The Universe Contents 3 HD 149026 B

History . 64 Antarctica . 136 Utopia Planitia . 209 Umbriel . 286 Comets . 338 In Popular Culture . 66 Great Barrier Reef . 138 Vastitas Borealis . 210 Oberon . 287 Borrelly . 340 The Amazon Rainforest . 140 Titania . 288 C/1861 G1 Thatcher . 341 Universe Mercury . 68 Ngorongoro Conservation Jupiter . 212 Shepherd Moons . 289 Churyamov- Orientation . 72 Area . 142 Orientation . 216 Gerasimenko . 342 Contents Magnetosphere . 73 Great Wall of China . 144 Atmosphere . .217 Neptune . 290 Hale-Bopp . 343 History . 74 History . 218 Orientation . 294 y Halle . 344 BepiColombo Mission . 76 The Moon . 146 Great Red Spot . 222 Magnetosphere . 295 Hartley 2 . 345 In Popular Culture . 77 Orientation . 150 Ring System . 224 History . 296 ONIS . 346 Caloris Planitia . 79 History . 152 Surface . 225 In Popular Culture . 299 ’Oumuamua . 347 In Popular Culture . 156 Shoemaker-Levy 9 . 348 Foreword . 6 Pantheon Fossae . 80 Clouds . 226 Surface/Atmosphere 301 Raditladi Basin . 81 Apollo 11 . 158 Oceans . 227 s Ring . 302 Swift-Tuttle . 349 Orbital Gateway . 160 Tempel 1 . 350 Introduction to the Rachmaninoff Crater . 82 Magnetosphere . 228 Proteus . 303 Universe . 8 Caloris Montes . 83 Lunar Eclipses . .161 Juno Mission . 230 Triton . 304 Tempel-Tuttle . 351 Scale of the Universe . 10 Sea of Tranquility . 163 Io . 232 Nereid . 306 Wild 2 . 352 Modern Observing Venus . 84 South Pole-Aitken Europa . 234 Other Moons . 308 Crater . 164 Methods . .12 Orientation . 88 Ganymede . 236 Oort Cloud . 353 Copernicus Crater . 165 Today’s Telescopes . 14. Atmosphere . 90 Callisto . 238 Non-Planetary Solar System Montes Apenninus . 166 How to Use This Book 16 History . 91 Objects . 310 Exoplanets . 354 Oceanus Procellarum .167 Naming Conventions . 18 In Popular Culture . -

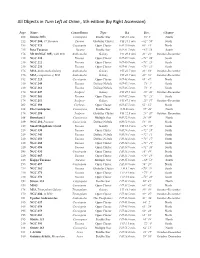

All Objects by Right Ascension For

All Objects in Turn Left at Orion , 5th edition (by Right Ascension) Page Name Constellation Type RA Dec. Chapter 188 Struve 3053 Cassiopeia Double Star 0 H 2.6 min. 66° 6' North 212 NGC 104, 47 Tucanae Tucana Globular Cluster 0 H 24.1 min −62° 58' South 193 NGC 129 Cassiopeia Open Cluster 0 H 29.8 min. 60° 14' North 215 Beta Tucanae Tucana Double Star 0 H 31.5 min. −62° 58' South 176 M110 (NGC 205), with M31 Andromeda Galaxy 0 H 40.3 min 41° 41' October–December 210 NGC 220 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.5 min. −73° 24' South 210 NGC 222 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 40.7 min. −73° 23' South 210 NGC 231 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 41.1 min. −73° 21' South 176 M31, Andromeda Galaxy Andromeda Galaxy 0 H 42.7 min 41° 16' October–December 176 M32, companion of M31 Andromeda Galaxy 0 H 42.7 min 40° 52' October–December 192 NGC 225 Cassiopeia Open Cluster 0 H 43.4 min. 61° 47' North 210 NGC 249 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 45.5 min. −73° 5' South 210 NGC 261 Tucana Diffuse Nebula 0 H 46.5 min. −73° 6' South 174 NGC 247 Sculptor Galaxy 0 H 47.1 min −20° 46' October–December 210 NGC 265 Tucana Open Cluster 0 H 47.2 min. −73° 29' South 174 NGC 253 Sculptor Galaxy 0 H 47.5 min −25° 17' October–December 202 NGC 188 Cepheus Open Cluster 0 H 47.5 min. -

Table of Contents – Fundamentals of Stargazing (March 2017 – February 2018)

Table of Contents – Fundamentals of Stargazing (March 2017 – February 2018) ** Solar System Observing Tools and Science of Month Sky Tours (North) Sky Tours (South) Deep-Sky Objects Observing Techniques Astronomy Layout of the sky: the Orion, Taurus, Gemini, Canis Visual observing - how Orion, Taurus, Canis Major, Hyades; Pleiades; Orion Nebula; Orion Layout of the solar celestial sphere, finding Major, Auriga; Monoceros, the eye sees faint Auriga; Monoceros and Lepus; OB1 Association; Crab Nebula; M41; system; a detailed the celestial poles, 1- March Lepus, and Columba; Puppis, objects; dark adaptation; Eridanus; Constellations vs. M36,37,38; M46 and M47; NGC2451 look at the planet equator, ecliptic; Eridanus; Constellations vs. averted vision; tools: red Asterisms and NGC2477 Jupiter measuring angular Asterisms flashlights distances Castor, M35, NGC2392 (Eskimo), Iota Can, M44 (Beehive), M67, M48, Regor Apparent motion of the Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Hydra, Geometry of the (Gamma Velorum) and NGC2547, Evaluating the night sky; night sky; celestial 2- April Gemini, Lynx, Cancer, Leo, Hydra Carina, Vela and the ‘False solar system; IC2391, NGC2516 (Southern Beehive), Estimating small angles coordinates; precession Cross’ Retrograde motion NGC3372 (Eta Carinae), NGC3293, of the equinoxes IC2602 (Southern Pleiades) M81 and M82; M97; Regulus; Leo Binoculars: How to Triplet; Cor Caroli and La Superba; Bootes, Corona Borealis, choose; image Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Bootes, M51; M3; Izar; Melotte 111; NGC 4565; Coma Berenices, Canes A detailed look -

Wolf-Rayet Stars in Local Group Giant Hii Regions

WOLF-RAYET STARS IN LOCAL GROUP GIANT HII REGIONS LAURENT DRISSEN Space Telescope Science Institute 3700 San Martin Drive Baltimore, MD 21218 ABSTRACT. We present the results of our search for WR stars in three of M33's most massive giant HII regions, namely NGC 604, NGC 595 and NGC 592. A few of the putative superluminous" WR stars are shown to be crowded multiple systems. We also compare the WR populations of the most massive GHRs in the Local Group. WN stars are 5 times more numerous on the average than WC stars in these large complexes. The variations among GHR WR populations are discussed in the context of metallicity and age differences. 1. Introduction Giant HII regions (GHRs) appear to be the most intense sites of star formation known in normal galaxies, and they offer the unique opportunity to study massive stars at their birthplace. Apart from 30 Dor in the LMC, the most massive GHRs in the Local Group, namely NGC 604 and NGC 595, are located in M33. The presence of WR stars in these regions is well known, but some uncertainties remain. We present our observations in section 2 and 3, and we compare the WR population of the best studied Local Group GHRs in section 4. 2· Observations Narrow-band images of NGC 604, NGC 595 and NGC 592 were obtained with an RCA CCD detector attached to the Mont Mégantic 1.6m telescope. A set of three filters was used to detect WR stars: 4780/65 (\c = 4780 A ; FWHM = 65 Â ) ; reference continuum 4686/35 ; detect He II 4686 in WNs 4650/29 ; detect CIII 4650 in WCs, NUI 4641 in WNs.