ABSTRACT OXENDINE, DAVID BRYAN. the Effects of Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memphis Is Made Possible By

2015-16 SEASON CT3 PEOPLE CON OTHER STAGES BOARD OF DIRECTORS ARTISAN CENTER THEATRE TUil 11AN'l'AS'l'Wl{S CHAIR ScottT. Williams APR 22 -JUN 4 Bye Bye Birdie by Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt BOARD MEMBERS CIRCLE THEATRE December 3 - 27, 2015 Marion L. Brockette, Jr., Suzanne Burkhead, APR 22 -JUN 4 Under the Skin RaymondJ. Clark, Sid Curtis, Katherine C. Eberhardt, Laura V. Estrada, Sally Hansen, David G. Luther, Jr., DALLAS CHILDREN'S THEATRE David M. May, Chris Rajczi, Margie J. Reese, Dana APR 28-MAY 21 TheBFG(BigFriendly Giant) W. Rigg, Elizabeth Rivera, Eileen Rosenblum, Ph.D. 'I' Bil Gl,AS S )IllNA Glllll ll on HONORARY BOARD MEMBERS DALLAS THEATRE CENTER by Tennessee Williams by Neil Tucker Virginia Dykes, Gary W. Grubbs, APR 20-MAY 14 DeferredAction July 30 -August 23, 2015 January 21 - February 14, 2016 John & Bonnie Strauss GARLAND CIVIC THEATRE APR 14-MAY 7 Hank Williams: Lost Highway ADMINISTRATION ACTING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Bruce R. Coleman MAINSTAGE ·IRVING• LAS COLINAS MAN AG I NG DIRECTOR Merri Brewer MAY13-28 TheGreatGatsby UGil'I' UP 'l'Dll SKY 111x Hll, .rnsus BOOKKEEPER Linda Harris by Helen Sneed by Moss Hart ONSTAGE IN BEDFORD COMPANY MANAGER Kat Edwards September 17- October 11, 2015 March 10 -April 3, 2016 MAY 20 -JUN 5 Kitchen Witches PUBLICITY, MARKETING & DESIGN SoloShoe Communications, LLC PEGASUS TH EATRE MAY 20 -29 CPA Ron King A 1rifleDead! HOUSEKEEPING Kevin Spurrier POCKET SANDWICH THEATRE PU)NW )lll)IPIIIS MAY 20 -JUN 18 Moon OverBuffalo by William Inge by David Br yan and Joe Di Pietro PRODUCTION October -

Bon Jovi's This House Is Not for Sale Tour to Launch

BON JOVI’S THIS HOUSE IS NOT FOR SALE TOUR TO LAUNCH FEBRUARY 2017 PRESENTED BY LIVE NATION New Album Release Date for This House Is Not for Sale set for Nov. 4th; Featured in The Ellen DeGeneres Show, ABC’s Good Morning America, Nightline, Charlie Rose, Howard Stern, People, Billboard American Express and Fan Club Ticket Pre-Sales Begin Oct. 10 at 10 a.m. Public Tickets On-Sale Oct. 15 at 10 a.m. October 5, 2016 – Grammy Award®-winning band, Bon Jovi today announced that the This House Is Not for Sale Tour, presented by Live Nation, will kick off in February 2017. Hitting arenas across the U.S., the iconic rock band will present anthems, fan favorites, and new hits from their upcoming 14th studio album, This House Is Not for Sale (out Nov. 4 on Island/UMG). As an added bonus, fans will receive a physical copy of This House Is Not For Sale with every ticket purchased. This will be the band’s first outing since Bon Jovi’s 2013 Because We Can World Tour, which was their third tour in six years to be ranked the #1 top-grossing tour in the world (a feat accomplished by only The Rolling Stones previously). Bon Jovi’s touring legacy will be recogniZed Nov. 9th with the 2016 “Legend of Live” award at the Billboard Touring Conference & Awards. As Bon Jovi rocks October to launch This House Is Not for Sale, the title track is already inside the Top Ten of the AC Radio Chart – it is Bon Jovi’s highest debut on that chart to date. -

KT.Season.Brochure.17-18.Pdf

ESCAPE WITH KELSEY THEATRE’S FULL-LENGTH PRODUCTIONS Get away from the trials and tribulations of the 21st century. Take a break from politics and profit margins, divisions and diversions, PIN-codes and passwords, and ESCAPE with Kelsey Theatre’s AMAZING 2017-2018 Season. MEMPHIS - SPECIAL EVENT Fridays, Sept. 8, 15, 2017 at 8pm NEIL SIMON’S BAREFOOT Saturdays, Sept. 9, 16 at 8pm IN THE PARK Sundays, Sept. 10, 17 at 2pm Fridays, Sept. 22 & 29, 2017 at 8pm Escape 2017 and travel back to 1950s Memphis, Tennessee! Saturdays, Sept. 23 & 30 at 8pm Winner of the Tony Award for Best Musical, Memphis is about Sundays, Sept. 24 & Oct. 1 at 2pm a radio DJ who wants to change the world and a club singer Newlyweds Paul and Corie couldn’t be more different -- he’s who is ready for her big break. It is set to an original score by a straight-laced lawyer, and she’s a free spirit who’s always Bon Jovi’s David Bryan that evokes the powerhouse funk of looking to break away on an adventure. Paul doesn’t James Brown, the hot guitar riffs of Chuck Berry, the smooth understand Corie’s relaxed ways, and she wants him to be harmonies of the Temptations, and the silken, bouncy pop more spontaneous, even running “barefoot in the park” of the era’s great girl groups. Turn up that dial as PinnWorth would be a start. Throw in a dilapidated apartment in a New Productions brings you this roof-raising rock ‘n’ roll musical! York brownstone, an eccentric neighbor, and a surprise visit from Corie’s mother, and The Yardley Players will tickle your funnybone, and touch your heart. -

Jon Bon Jovi

Jon Bon Jovi Jon Bon Jovi is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and actor, best known as the lead singer and founder of Bon Jovi. Throughout his career, he has released two solo albums and eleven studio albums with his band which have sold over 200 million albums worldwide. Jon Bon Jovi was born John Francis Bongiovi, Jr. in Perth Amboy, New Jersey the son of two former Marines, barber John Francis Bongiovi, Sr. and florist Carol Sharkey. He has two brothers, Anthony and Matthew. His father was of Sicilian and Slovak ancestry and his mother was of German and Russian descent. He has stated that he is a blood relative of Frank Sinatra. He spent summers in Erie, Pennsylvania, with his grandparents as a newspaper salesman. As a child, Bon Jovi attended St. Joseph High School, in Metuchen, New Jersey, during his freshman and sophomore years. He later transferred to Sayreville War Memorial High School in Parlin, New Jersey. // 1 / 9 Jon Bon Jovi Bon Jovi spent most of his adolescence bunking school to opt for music activities instead, and ended up playing in local bands with friends and his cousin Tony Bongiovi, who owned the then famous New York recording studio, The Power Station. As a result, his academic records displayed less than spectacular achievements and poor grades. By the time he was 16, Bon Jovi was playing clubs. It was not long before he hooked up with keyboardist David Bryan (real name: David Bryan Rashbaum), who played with him in a ten-piece rhythm and blues band called Atlantic City Expressway. -

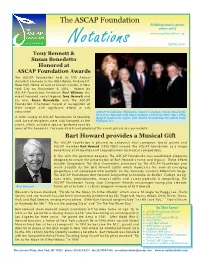

Notations Spring 2011

The ASCAP Foundation Making music grow since 1975 www.ascapfoundation.org Notations Spring 2011 Tony Bennett & Susan Benedetto Honored at ASCAP Foundation Awards The ASCAP Foundation held its 15th Annual Awards Ceremony at the Allen Room, Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York City on December 8, 2010. Hosted by ASCAP Foundation President, Paul Williams, the event honored vocal legend Tony Bennett and his wife, Susan Benedetto, with The ASCAP Foundation Champion Award in recognition of their unique and significant efforts in arts education. ASCAP Foundation Champion Award recipients Susan Benedetto (l) & Tony Bennett with Mary Rodgers (2nd from left), Mary Ellin A wide variety of ASCAP Foundation Scholarship Barrett (2nd from right), and ASCAP Foundation President Paul and Award recipients were also honored at the Williams (r). event, which included special performances by some of the honorees. For more details and photos of the event, please see our website. Bart Howard provides a Musical Gift The ASCAP Foundation is pleased to announce that composer, lyricist, pianist and ASCAP member Bart Howard (1915-2004) named The ASCAP Foundation as a major beneficiary of all royalties and copyrights from his musical compositions. In line with this generous bequest, The ASCAP Foundation has established programs designed to ensure the preservation of Bart Howard’s name and legacy. These efforts include: Songwriters: The Next Generation, presented by The ASCAP Foundation and made possible by the Bart Howard Estate which showcases the work of emerging songwriters and composers who perform on the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage. The ASCAP Foundation Bart Howard Songwriting Scholarship at Berklee College recog- nizes talent, professionalism, musical ability and career potential in songwriting. -

Bon Jovi Dedicates Song

THE JEWISH LEADER, OCTOBER 9, 2015 13 Bon Jovi dedicates song ‘We Don’t Run’ to Israel At packed, rapturously received Tel Aviv concert, when a Palestinian man stabbed two Israelis to New Jersey rocker tells his Jewish keyboard player, death in the Old City, and injured two others. ‘Your father would be proud of you’ “Good evening Tel Aviv, Israel! Are you ready for rock ‘n roll? I’ve waited a long time for this, By Times of Israel Staff baby!” Bon Jovi called out to fans packed into Tel Aviv’s Yarkon Park before opening with the performance in Israel Saturday evening, Octo- song “That’s What the Water Made Me.” berJon 3 byBon telling Jovi kicked 50,000 off cheering his band’s Israelis first-ever “I’ve waited a long time for this!” time, and we still have a ways to go tonight. Are A few songs into the show, he underlined you“We with finally me?” hemade asked. it here. It took us a long his empathy with Israel by introducing a new In an 18-song setlist, fans were treated to song called “We Don’t Run,” released earlier this some of Bon Jovi’s newer material as well as summer, with the comment: “This should be the the group’s biggest hits, including “You Give Love a Bad Name,” “It’s My Life,” and, at the end And later in the performance, the New Jersey- of the long set, “Livin on a Prayer.” Bon Jovi members in Israel on Friday. From left: Drummer Tico fightborn songrocker for name-checked Tel Aviv.” his keyboard player, The 53-year-old musician was upbeat and Torres, keyboard player David Bryan, and singer Jon Bon Jovi. -

Honorable David Bryan Sentelle

HONORABLE DAVID BRYAN SENTELLE Oral History Project The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit Oral History Project United States Courts The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit District of Columbia Circuit HONORABLE DAVID BRYAN SENTELLE Interviews conducted by David C. Frederick, Esquire July 7 and 8 and August 12 and 13, 2003 November 6, 2003, January 16, 2004, August 7, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface. ................................................................................................................................ i Oral History Agreements Honorable David Sentelle ......................................................................................... iii Ann Allen, Esquire......................................................................................................v Oral History Transcripts of Interviews July 7, 2003 .................................................................................................................1 July 8, 2003 ...............................................................................................................67 August 12, 2003 ......................................................................................................130 August 13, 2003 ......................................................................................................178 November 6, 2003 ...................................................................................................226 January 16, 2004 .....................................................................................................281 -

Duncan Stewart, CSA and Benton Whitley, CSA, Casting Directors

Duncan Stewart, CSA and Benton Whitley, CSA, Casting Directors/Partners Paul Hardt, Christine McKenna-Tirella, CSA Casting Director Ian Subsara, Emily Ludwig Casting Assistant Resume as of 3.15.2019 _________________________________________________________________ CURRENT & ONGOING: HADESTOWN Theater, Broadway – Walter Kerr Theater March 2019 – Open Ended Mara Isaacs, Hunter Arnold, Dale Franzen (Prod.) Rachel Chavkin (Dir.), David Newmann (Choreo.) By: Anais Mitchell CHICAGO THE MUSICAL Theater, Broadway – Ambassador Theater May 2008 – Open Ended Barry and Fran Weissler (Prod.) Walter Bobbie (Dir.), Ann Reinking (Choreo.) By: John Kander & Fred Ebb CHICAGO THE MUSICAL Theater, West End – Phoenix Theater March 2018 – Open Ended Barry and Fran Weissler (Prod.) Walter Bobbie (Dir.), Ann Reinking (Choreo.) By: John Kander & Fred Ebb ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST NBC Lionsgate TV Pilot March 2019 Richard Shepard (Dir.), Austin Winsberg (Writer) NY Casting AUGUST RUSH Theater, Regional – Paramount Theater January 2019 – June 2019 Paramount Theater (Prod.) John Doyle (Dir.), JoAnn Hunter (Choreo.) By: Mark Mancina, Glen Berger, David Metzger PARADISE SQUARE: An American Musical Theater, Regional – Berkeley Repertory Theatre December 2018 – March 2019 Garth Drabinsky (Prod.) ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Stewart/Whitley 213 West 35th Street Suite 804 New York, NY 10001 212.635.2153 Moisés Kaufman (Dir.), Bill T. Jones (Choreo.) By: Marcus Gardley, Jason Howland, Larry Kirwan, Craig Lucas, Nathan -

To Read the Program Online

The Artistic Director’s Circle Season Sponsors Michael Bartell & Melissa Garfield Bartell Gail & Ralph Bryan Brian & Silvija Devine Joan & Irwin Jacobs Sheri L. Jamieson Becky Moores The Rich Family Foundation The Hearst Foundations, The William Hall Tippett & Ruth Rathell Tippett Foundation, Dr. Seuss Fund at The San Diego David C. Copley Foundation, The Mandell Weiss Charitable Trust, Anonymous, Foundation Foster Family Fund of the Jewish Community Foundation, Kay & Bill Gurtin, Steven Strauss & Lise Wilson Lynn Gorguze & The Honorable Scott Peters, Vivien & Jeffrey Ressler Family Fund of the Jewish Community Foundation, and Molli Wagner PRODUCTION SPONSORS Gail & Ralph Bryan Brian & Silvija Devine SEPTEMBER 22 – OCTOBER 21 LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE PRESENTS A MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Christopher Ashley Debby Buchholz Artistic Director Managing Director All art is personal. Whatever the medium, whatever the style – comedic or tragic, MISSION STATEMENT: fantastical or realistic – artists create work from a deeply individual point of view to grapple with and better understand La Jolla Playhouse advances theatre as themselves and the society in which they live. When you see a play, an art form and as a vital social, moral you are granted special insight into the world of its author. and political platform by providing unfettered creative opportunities A show like Hundred Days, however, ups the ante. With startling and for the leading artists of today and breathtaking emotional honesty, Abigail and Shaun Bengson relate BOOK BY MUSIC AND LYRICS BY tomorrow. With our youthful spirit and the story of how their separate trajectories brought them together, THE BENGSONS AND SARAH GANCHER THE BENGSONS eclectic, artist-driven approach, we and how that breathless feeling of attachment can lead to exhilaration will continue to cultivate a local and about what has been created, and terror at what can be taken national following with an insatiable away. -

A Christmas Carol 2014 the Drowsy Chaperone

WIG MASTER/MAKEUP ARTIST/WIG INSTRUCTOR 801- 573-5910 - LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA - IATSE LOCAL #488 UTAH FESTIVAL OPERA COMPANY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN INDIANA UNIVERSITY AND MUSICAL THEATRE (UFOMT) La Traviata Cosi fan tutti Madame Butterfly, The Music Man, GREENSBORO OPERA COMPANY UTAH FESTIVAL OPERA The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Un Ballo in Maschera The Magic Flute, Die Fledermaus, The The Pirates of Penzance OLD LYRIC REPERTORY COMPANY Desert Song, Fiddler On The Roof, Madam Butterfly, Nabucco, HALE CENTER THEATRE The Drowsy Chaperone Susannah, South Pacific, Naughty A Christmas Carol 2014 AUGUSTA OPERA Marietta, The Wizard of Oz, Carmen, Faust, Oklahoma The Barber of Seville, The Mikado, UC IRVINE SEATTLE OPERA YOUNG ARTIST Into the Woods Julius Caesar, The Tales of Hoffman La Boheme, Cosi fan tutti THE OLD GLOBE SEATTLE OPERA HARTFORD STAGE COMPANY First Wives Club Norma, Carmen, Fidelio, Lohengrin, Cymbeline, Tin Types, sueno, Mourning Becomes Electra, Onegin, Intimate Exchanges, Servant of Two Ariadne auf Naxos, La fanciulla Masters, The Colored Museum JERSEY BOYS VIVA VEGAS COMPANY NEW YORK CITY CENTER ROUNDABOUT THEATRE COMPANY Jersey Boys, Las Vegas Gypsy, with Patti LuPone The Women SAN DIEGO OPERA LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE NETWORKS NATIONAL TOUR Nabucco, Carmen Bonnie and Clyde Show Boat UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN RADIO CITY MUSIC HALL ATLANTA OPERA COMPANY Anything Goes Rockettes Christmas Spectacular Amahl and the Night Visitors PIEDMONT OPERA OPERA CAROLINA COLORADO SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Manon, Tosca Candide 1993-99 The Cannon SAN DIEGO -

Matinee Handout 19/20

WEATHERVANE PLAYHOUSE SCHOOL MATINEE PERFORMANCES Weathervane Playhouse is dedicated to the belief that young people should have the opportunity to participate in theatre both as audience members and as artists. Through this program we use live performances to awaken, enliven, and challenge the minds of students with issues both interesting and relevant to our time. School Matinee Prod uctions include: -A study guide to prepare for the performance and enhance your theatre experience -Reduced price tickets ($7.00 per student/teacher) -An optional post-performance talk-back with actors, director, and technical staff Interested in a pre-show discussion or program with your students? We will come to your school! 2019-2020 Matinee Performance Season Theatre Tours Music & Lyrics: David Bryan Lyrics by Tim Rice Book & Lyrics: Joe DiPietro Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber Receive a Inspired by actual events, Memphis is about a The Biblical saga of Joseph and his coat of many backstage pass and white radio DJ in the 1950’s who wants to colors comes to vibrant life in this delightful take a tour of change the world and a black club singer who musical parable! Joseph and the Amazing Weathervane! Tours is ready for her big break. Come along on their Technicolor Dreamcoat is a re-imagining of the incredible journey to the ends of the airwaves Biblical story of Joseph. Set to an engaging are only $2.00 per – filled with laughter, soaring emotion, and cornucopia of musical styles, from country- person! roof-raising rock ‘n’ roll. Winner of four 2010 western to pop and rock 'n' roll, this tale emerges Tony Awards including Best Musical and two both timely and timeless. -

Richie Sambora the Last Three Bon Jovi Records, My Solos Matter of Influences

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM MUSICIAN Why make a solo album now? Did that affect your playing today? TOOLS OF THE TRADE There were many reasons. Bon Jovi had I think so. Once I realized the pentatonic been ultra-busy to the point that I didn’t have scale was a movable thing, up and down time to stop and look at what was happening the neck in any key, I became a lead player Sambora tore into his vast vintage in my life. At the end of our last tour—after quickly. I was in a band within six months instrument collection for Aftermath of the traveling to 52 countries in 18 months—I of picking up the guitar, playing lead solos. Lowdown. “I used everything from a 1959 finally had a chance to think about myself. I It helped that I was an avid music listener. Les Paul to a ’58 Flying V to some ’50s Fender came home energized and started to write I bought a new album every week or two Broadcasters,” he says. “I even used an original songs. I had no idea I was making an album, and really studied them. It also helped that Gibson Explorer. I also used lots of Strats—’61s but as the songs started to take shape, they I had played the accordion, and the sax and ’63s—and lots of Gretsches, including a turned out to be very reflective of where I am and trumpet in the school band. Those 1954 Country Gentleman, a 6120 and a in my life.