Ecosystem-Based Management: Public Comments Received 1/24/2011-4/29/2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Situ Tagging and Tracking of Coral Reef Fishes from the Aquarius Undersea Laboratory

TECHNICAL NOTE In Situ Tagging and Tracking of Coral Reef Fishes from the Aquarius Undersea Laboratory AUTHORS ABSTRACT James Lindholm We surgically implanted coded-acoustic transmitters in a total of 46 coral reef fish Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary; during a saturation mission to the Aquarius Undersea Laboratory in August 2002. Current address: Pfleger Institute of Aquarius is located within the Conch Reef Research Only Area, a no-take marine re- Environmental Research serve in the northern Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Over the course of 10 Sarah Fangman days, with daily bottom times of 7 hrs, saturation diving operations allowed us to col- Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary lect, surgically tag, release, and subsequently track fishes entirely in situ. Fish were collected using baited traps deployed adjacent to the reef as well as nets manipulated Les Kaufman on the bottom by divers. Surgical implantation of acoustic transmitters was conducted Boston University Marine Program at a mobile surgical station that was moved to different sites across the reef. Each fish Steven Miller was revived from anesthetic and released as divers swam the fish about the reef. Short- National Undersea Research Center, term tracking of tagged fish was conducted by saturation divers, while long-term fish University of North Carolina at Wilmington movement was recorded by a series of acoustic receivers deployed on the seafloor. Though not designed as an explicit comparison with surface tagging operations, the benefits of working entirely in situ were apparent. INTRODUCTION he use of acoustic telemetry to track the movements of marine fishes is now a com- true with deepwater fishes that have air blad- fish with a damp towel. -

October 21St 2013

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Coyote Chronicle (1984-) Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 10-21-2013 October 21st 2013 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle Recommended Citation CSUSB, "October 21st 2013" (2013). Coyote Chronicle (1984-). 113. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle/113 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coyote Chronicle (1984-) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. XLVII, No. 4 COYOTECHRONICLE.NET THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT VOICE OF CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SAN BERNARDINO SINCE 1965 MONDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2013 Coyote Chronicle 05 10 08 14 Laziness gets in the CSUSB celebrates 18th Student artist illustrates Intramural Volleyball way of knowledge annual Pow Wow her style on campus now available! By DANIEL DEMARCO McConnell (Republican leader for Kentucky). Staff Writer Both the Senate and the House of Repre- sentatives approved the plan. On Oct. 16, 2013, President Barack According to Aljazeera, the Senate passed Obama signed a deal passed by Congress, end- the deal by 81 votes to 18 and the House passed ing the partial government shutdown. it, 285 votes to 144. Cutting it very close, Obama offi cially The shutdown began on Oct. 1, when Re- Shutdown signed the deal around 9:30 p.m. the night be- publicans refused to agree to temporary gov- fore the country lost its ability to continue bor- ernment funding which would push the debt rowing money. -

BELLEVILLE - the Town That Pays As It Goes

SS--------------------------------- r,— BELLEVILLE - The Town That Pays As It Goes Progressive business people adver Each issue of The News contains tise in The News each week. Fol hundreds of items of interest. The low the advertisements closely and give Belleville,a big share in your well-informed read the News thor purchases. oughly each week. BELLEVILLE NEWS Entered as Second Class Mail Matter, at Newark, N. J., Post Office, Under Act of March 3, 1879, on October 9, 1925. VoL X III, No. 9. PRICE FIVE CENTS OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER—TOWN OF BELLEVILLE BELLEVILLE, N. J., FRIDAY, OCTOBER 22, 1937 Police Busy with School Board Frowns on Competition Í The Lake 1/ohn Hewitt Outlines Relief Series of Accidents A portion of Silver Lake section Situation at Rotary Meeting With Printers and Restaurants became a lake. Wednesday morning We wouldn’t believe that it was One Man Struck While Let* possible if we hadn’t read it with our due to the torrential rain that fell Tuesday night and Wednesday Director Of Welfare Department Tells Of Decided own eyes. O f course, Toni Harrison School Print Shop Had Been Working “Ail Hours” on ting Air Out of isn’t employed by the Herdman Chev morning. Residents of the section, es Drop In Case Load In The rolet Company, as we stated in last Outside Work, Authorities Tire week’s column. He is the T. W. Har pecially those in North Belmont avenue, complained of the water Last Year rison of T. W. Harrison, Inc., dealer Learn A series of accidents, starting last seeping into their cellars from the in He Soto and Plymouth automobiles. -

PDF of This Issue

MIT’s The Weather Today: Cloudy, windy, 32°F (0°C) Oldest and Largest Tonight: Clear, windy, 25°F (-4°C) Tomorrow: Clear, windy, 39°F (4°C) Newspaper Details, Page 2 Volume 126, Number 8 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, March 3, 2006 Media Lab Post-Doc Found Dead Tuesday By Jenny Zhang in Dedham. He “seemed a little and Marie Y. Thibault down at the time,” and Winston said NEWS EDITORS he thought at the time that it was be- MIT Media Laboratory post-doc- cause of the back pain. “He gave a toral associate Pushpinder Singh ’98 great talk” and “we were all looking was found dead in his apartment by forward to the next one,” Winston his girlfriend on Tuesday, Feb. 28, said. according to Senior Associate Dean Singh received both his Master for Students Robert M. Randolph. of Engineering and PhD in Electrical The death is being investigated Engineering and Computer Science by the Middlesex District Attorney, from MIT. According to his Web site, said MIT Police Chief John DiFava, Singh would have joined Media Lab who would not further comment on faculty next year. the circumstances surrounding the Bo Morgan G, who was advised death. by Singh through his undergraduate However, EECS professor Pat- and graduate years, said Singh “had rick H. Winston ’65 said in his class a way of showing people the future,” Wednesday that the cause of death and inspired students. Singh studied was suicide. Winston said he had said the most abstract aspects of artificial that at the time based on speculation, intelligence, Morgan said. -

2018 Annual Report American Indian Science and Engineering Society Aises We Are Indigenous • We Are Scientists

2018 ANNUAL REPORT AMERICAN INDIAN SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING SOCIETY AISES WE ARE INDIGENOUS • WE ARE SCIENTISTS AISES Council of Elders Dr. Grace Bulltail (Crow Tribe/descendant of MHA Nation) Education Committee Chair Dr. Bret R. Benally Thompson (White Earth Ojibwe) Shaun Tsabetsaye (Zuni Pueblo) (Navajo) Antoinelle Benally Thompson Professional Development Committee Chair Steve Darden (Navajo/Cheyenne/Swedish) Barney “BJ” Enos (Gila River Indian Community) Rose Darden (Ute) Dr. John B. Herrington (Chickasaw) Norbert Hill, Jr. (Oneida) Dr. Adrienne Laverdure (Turtle Mountain Band of Phil Lane Jr. (Yankton Dakota/Chickasaw) Chippewa) Stan Lucero (Laguna Pueblo) * Alicia Jacobs (Cherokee) (Acoma Pueblo) Vice Chairwoman/Nominations Committee Chair Cecelia Lucero Nov. 2018 – July 2019 Dr. Henrietta Mann (Southern Cheyenne) Faith Spotted Eagle (Ihanktonwan Band of the Dakota/ Nakota/Lakota Nation of South Dakota) 2017 - 2018 AISES Board of Directors Council of Elders Emeriti Dr. Twyla Baker (Three Affiliated Tribes) Andrea Axtell (Nez Perce) Chairwoman Mary Kahn (Navajo) Richard Stephens (Pala Band of Mission Indians) Vice Chairman Michael Laverdure (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa) Council of Elders in Memoriam Treasurer/Finance Committee Chair Horace Axtell (Nez Perce) Amber Finley (Three Affiliated Tribes) Eddie Box, Sr. (Southern Ute) Secretary/Membership Committee Chair (Navajo) Franklin Kahn Bill Black Bow Lane (Chickasaw) Governance Committee Chair Phil Lane, Sr. (Yankton Sioux) Shaun Tsabetsaye (Zuni Pueblo) Dr. James May (United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Professional Development Committee Chair Indians) Alicia Jacobs (Cherokee) Lee Piper, PhD. (Cherokee) Nominations Committee Chair Dr. Grace Bulltail (Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara 2018 - 2019 AISES Board of Education Committee Chair Directors Barney “B.J.” Enos (Gila River Indian Community) Kristina Halona (Navajo) Rick Stephens (Pala Band of Mission Indians) Chairman Dr. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

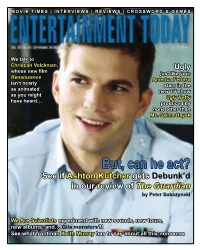

But, Can He Act? See If Ashton Kutcher Gets Debunk’D in Our Review of the Guardian by Peter Sobczynski

MOVIE TIMES | INTERVIEWS | REVIEWS | CROSSWORD & GAMES We talk to Christian Volckman, Ugly whose new film just like you: Renaissance America Ferrera isn’t nearly stars in the as animated new TV show as you might Ugly Betty have heard… produced by none other than Ms. Salma Hayek But, can he act? See if Ashton Kutcher gets Debunk’d in our review of The Guardian by Peter Sobczynski We Are Scientists experiment with new sounds, new tours, new albums, and… Gila monsters?! See what frontman Keith Murray has to say about all this nonsense || SEPTEMBER 29-OCTOBER 5, 2006 ENTERTAINMENT TODAY a “Sensational!” WMK Productions, Inc. Presents —Chicago Tribune “A joyous celebration Three Mo’ Tenors that blows the roof off the house!” Fri.–Sat., Oct. 6–7, 8 pm —Boston Herald Three Mo’ Tenors, the highly acclaimed music sensation, returns to the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. This talented trio of African-American opera singers belts out Broadway’s best, and performs heaven-sent Gospel music in a concert event for the entire family. Tickets: $63/$50/$42 Friday $67/$55/$45 Saturday Conceived and Directed by Marion J. Caffey Call (562) 467-8804 today to reserve your seats or go on-line to www.cerritoscenter.com. The Center is located directly off the 91 freeway, 20 minutes east of downtown Long Beach, 15 minutes west of Anaheim, and 30 minutes southeast of downtown Los Angeles. Parking is free. Your Favorite Entertainers, Your Favorite Theater . || ENTERTAINMENT TODAY SEPTEMBER 29-OCTOBER 5, 2006 ENTERTAINMENTVOL. 38|NO. 51|SEPTEMBER 29-OCTOBER 5, 2006 TODAYINCE S 1967 PUBLISHER KRIS CHIN MANAGING EDITOR CECILIA TSAI EDITOR MATHEW KLICKSTEIN PRODUCTION DAVID TAGARDA GRAPHICS CONSULTANT AMAZING GRAPHICS TECHNICAL SUPERVISOR KATSUYUKI UENO WRITERS JESSE ALBA JOHN BARILONE FRANK BARRON KATE E. -

Firing Back on the Fee OC Music Awards Rolls out Red Carpet

WEDNESDAY, MARCH 5, 2014 Volume 95, Issue 20 Students gear up for Greek Week festivities the kids.” Proceeds from The fraternities and activities will help sororities raise mon- ey by getting donations fund Camp Titan from local business- MICHAEL HUNTLEY es and having their own Daily Titan fundraisers. “Every sorority and every fraternity will ei- This weekend, Cal State ther do some fundrais- Fullerton Greek organi- ing, (such as going) to zations will be partici- Pieology and if you buy pating in Greek Week in a pizza a certain per- an effort to raise money centage will go toward for Camp Titan. Greek Week,” said Missy Every June, Camp Titan Mendoza, a junior com- WINNIE HUANG / Daily Titan takes about 150 children munications major and Carie Rael, a history graduate student, holds a sign during the Pizza with the Presidents panel Tuesday in the Quad. to the San Bernardino member of the Alpha Mountains to introduce Delta Pi sorority on cam- them to nature, heighten pus. “Or we’ll go out to their self-awareness, in- local businesses, and be- crease their confidence cause it’s a tax write-off and help them make new they’ll donate money.” Firing back on the fee friends. Greek programs get do- The counselors at nations from alumni as Students criticize Camp Titan are student well. volunteers. “Since Camp Titan has campus leaders But sending the chil- been around for a cou- during “Pizza” panel dren and the counselors ple years now and a lot of to the mountains is cost- alumni know about Greek KYLE NAULT ly. -

U Writers / Gonna Guetta Stomp Two New House Influenced Tracks

Interpret Titel Info !!! (Chk Chk Chk) All U Writers / Gonna Guetta Stomp Two new house influenced tracks. (INTERNATIONAL) NOISE CONSPIRACY, 500 Stück - rotes Vinyl, ausführliche Linernotes, 2 exklusive THE Live At Oslo Jazz Festival 2002 non-Album-Tracks 16 Horsepower FOLKLORE 180-gram vinyl /special edition / one-time only 16 Horsepower OLDEN 180-gram vinyl /special edition / one-time only 2 Bears, The Bears In Space 12" with CD 4 Promille Vinyl 7" Single / Etched B-Side 4 Promille Vinyl 7" Single / Etched B-Side / Colored Vinyl A Coral Room I.o.T. RSD 2015 YOU'LL ALWAYS BE IN MY STYLE / THE BOY FROM Ad Libs, The NYC Two highly prized sides back-to-back for the first time A special pressing for the RECORD STORE DAY 2015 and is Agathocles MINCER (RSD 2015) limited to 100 hand numbered copies. It will come in clear Limited edition White colored version in 100 copies Ages Malefic Miasma worldwide. a-ha Take On Me Picture to be images from the classic video. Playground Love / Highschool Lover 7" from The Virgin Air Playground Love Suicides coloured vinyl Alex Harvey Midnight Moses / Jumping Jack Flash Issued7" in 1975, this is the articulation of Zambia's Zamrock Amanaz Africa ethos. Amon Tobin Dark Jovian Five brand new productions. Vinylauflage der neuen Ausgabe der Compilationserie "A Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble". 16 der insgesamt 33 Tracks von Künstlern wie Tame Impala, Cybotron oder Russell Amorphous Androgynous A Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble / The Wizards Of Oz Morris. Schwarzes Doppel-Vinyl. ANGELIC UPSTARTS LAST TANGO IN MOSCOW LP Animal Collective Prospect Hummer RSD 2015 Animals, The WE'RE GONNA HOWL TONIGHT LP Combines truly amazing song-craft with Victorian tragedy and Annabel (Lee) By The Sea And Other Solitary Places grainy folk roots. -

Keith Murray

Interview with We Are Scientists’ Keith Murray New York indie rockers by way of Berkley, Calif., We Are Scientists are one of those acts that aren’t afraid to push boundaries and try out different things. One song will be a Fugazi-tinged alt-punk scorcher while another can sound like a mainstream pop hit. They’re currently in the midst of “The Splatter Analysis Tour” with Floridian indie rockers Surfer Blood and Roanake, Va., psych-shoegaze act Eternal Summers. I had a chance to chat with guitarist and vocalist Keith Murray about working with Ash’s Tim Wheeler, America vs. The UK and a special little 7″ vinyl available at their shows. Rob Duguay: On October 1, We Are Scientists will perform at The Sinclair in Cambridge, Mass., as part of “The Splatter Analysis Tour” with Surfer Blood and Eternal Summers. There will be a special joint vinyl that’ll be sold at the show as well. Can you tell us a little about what to expect from the 7″? Keith Murray: “Distillery” was a song we wrote and recorded in the very early stages of writing TV En Français. We spent a day in a studio in London and recorded three or four songs as potential demos. As we kept writing for the album, though, the tone of the record as a whole started to shift, and we didn’t quite feel that the songs we’d already tracked quite fit with the new batch of tunes we were working on. We really loved those songs though, and “Distillery” was our favorite of that batch, so we leapt at the chance to use it for something as cool as a split 7″ with the Surfer Blood gang. -

Uk Versus Usa at the Shockwaves Nme Awards 2007

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 8PM MONDAY 29 TH JANUARY Insert logo UK VERSUS USA AT THE SHOCKWAVES NME AWARDS 2007 Expect blood, sweat and tears as we prepare for what will undoubtedly be one big dirty rock’n’roll battle of the bands – and of the nations – at the Shockwaves NME Awards 2007 . The best of British – Arctic Monkeys , Muse and Kasabian – will take on stateside success stories My Chemical Romance and The Killers on March 1 at Hammersmith Palais. Let battle commence! This year, there’s no one clear leader but FIVE bands that dominate the nominations list. With four nominations each, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Kasabian, The Killers and My Chemical Romance have been chosen by the fans to fight it out on the night. For the past two years, it’s been British bands sweeping the board, but this year The Killers and My Chemical Romance may very well make the 2007 ceremony a stateside success story. Arctic Monkeys made NME Awards history last year by scooping the Award for both Best New Band and Best British Band in the same year, in addition to winning Best Track and scoring a nomination for Best Live Band . Sheffield’s favourites have matched their achievement, with four nominations this year for Best British Band, Best Live Band, Best Album and Best Music DVD. Arctic Monkeys said: “Very nice, we didn’t think we would get any this year! It seems weird for us to be alongside them [the competition] because we still feel like a little band. When it’s your own thing you don’t really see yourself alongside The Killers and Kasabian.” The Monkeys have more than one tough fight on their hands if they want to claim the Best British Band title for the second year running, though. -

Deepsea Coral Statement

Scientists’ Statement on Protecting the World’s Deep-Sea Coral and Sponge Ecosystems As marine scientists and conservation biologists, we are profoundly concerned that human activities, particularly bottom trawling, are causing unprecedented damage to the deep-sea coral and sponge communities on continental plateaus and slopes, and on seamounts and mid-ocean ridges. Shallow-water coral reefs are sometimes called “the rainforests of the sea” for their extraordinary biological diversity, perhaps the highest anywhere on Earth. However, until quite recently, few people—even marine scientists—knew that the majority of coral species live in colder, darker depths, or that some of these form coral reefs and forests similar to those of shallow waters in appearance, species richness and importance to fisheries. Lophelia coral reefs in cold waters of the Northeast Atlantic have over 1,300 species of invertebrates, and over 850 species of macro- and megafauna were recently found on seamounts in the Tasman and Coral Seas, as many as in a shallow-water coral reef. Because seamounts are essentially undersea islands, many seamount species are endemics—species that occur nowhere else—and are therefore exceptionally vulnerable to extinction. Moreover, marine scientists have observed large numbers of commercially important but increasingly uncommon groupers and redfish among the sheltering structures of deep-sea coral reefs. Finally, because of their longevity, some deep-sea corals can serve as archives of past climate conditions that are important to understanding global climate change. In short, based on current knowledge, deep-sea coral and sponge communities appear to be as important to the biodiversity of the oceans and the sustainability of fisheries as their analogues in shallow tropical seas.