On the Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mechanic the Secret World of the F1 Pitlane Marc 'Elvis' Priestley

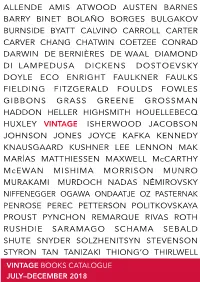

ALLENDE AMIS ATWOOD AUSTEN BARNES BARRY BINET BOLAÑO BORGES BULGAKOV BURNSIDE BYATT CALVINO CARROLL CARTER CARVER CHANG CHATWIN COETZEE CONRAD DARWIN DE BERNIÈRES DE WAAL DIAMOND DI LAMPEDUSA DICKENS DOSTOEVSKY DOYLE ECO ENRIGHT FAULKNER FAULKS FIELDING FITZGERALD FOULDS FOWLES GIBBONS GRASS GREENE GROSSMAN HADDON HELLER HIGHSMITH HOUELLEBECQ HUXLEY ISHERWOOD JACOBSON JOHNSON JONES JOYCE KAFKA KENNEDY KNAUSGAARD KUSHNER LEE LENNON MAK MARÍAS MATTHIESSEN MAXWELL McCARTHY McEWAN MISHIMA MORRISON MUNRO MURAKAMI MURDOCH NADAS NÉMIROVSKY NIFFENEGGER OGAWA ONDAATJE OZ PASTERNAK PENROSE PEREC PETTERSON POLITKOVSKAYA PROUST PYNCHON REMARQUE RIVAS ROTH RUSHDIE SARAMAGO SCHAMA SEBALD SHUTE SNYDER SOLZHENITSYN STEVENSON STYRON TAN TANIZAKI THIONG’O THIRLWELL TVINTAGEHORPE BOOKS THU CATALOGUEBRON TOLSTOY TREMAIN TJULY–DECEMBERYLER VARGAS 2018 VONNEGUT WARHOL WELSH WESLEY WHEELER WIGGINS WILLIAMS WINTERSON WOLFE WOOLF WYLD YATES ZOLA ALLENDE AMIS ATWOOD AUSTEN BARNES BARRY BINET BOLAÑO BORGES BULGAKOV BURNSIDE BYATT CALVINO CARROLL CARTER CARVER CHANG CHATWIN COETZEE CONRAD DARWIN DE BERNIÈRES DE WAAL DIAMOND DI LAMPEDUSA DICKENS DOSTOEVSKY DOYLE ECO ENRIGHT FAULKNER FAULKS FIELDING FITZGERALD FOULDS FOWLES GIBBONS GRASS GREENE GROSSMAN HADDON HELLER HIGHSMITH HOUELLEBECQ HUXLEY ISHERWOOD JACOBSON JOHNSON JONES JOYCE KAFKA KENNEDY KNAUSGAARD KUSHNER LEE LENNON MAK MARÍAS MATTHIESSEN MAXWELL McCARTHY McEWAN MISHIMA MORRISON MUNRO MURAKAMI MURDOCH NADAS NÉMIROVSKY NIFFENEGGER OGAWA ONDAATJE OZ PASTERNAK PENROSE PEREC PETTERSON POLITKOVSKAYA PROUST PYNCHON -

Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe @300 Grant Glass Over 300 Years

Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe @300 Grant Glass Over 300 years ago, Daniel Defoe immortalized the story of Robinson Crusoe with the publication of The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe—creating long tradition of stories about being marooned in an inhospitable place understood as the Robinsonade genre. While the intimate details of Crusoe’s story might be unfamiliar, many of its adaptations like The Martian or Cast Away still persist. Those are just a few, if you look closely enough, there are religious, survivalist, social gospel, colonizationist and anti-colonial, martially masculine, feminist Robinsonades, in overlapping circles emanating out from this central text. The best estimates place these variants in the hundreds. Yet the original novel provides the reader with a gauntlet of historical baggage ranging from colonialism and slavery to climate change and industrialization—forcing us to confront not only our past, but how we represent it in the present. What, then, is Crusoe’s legacy at 300, and what do its retellings tell us about how we think of our past and our future? When you start to notice the Robinsonade, it appears everywhere, and you start to realize you cannot put the horse back in the stable when it comes to Crusoe. Long before the days of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Lena Dunham, Crusoe became an international phenomenon on the star power of its writer, Daniel Defoe, who much like a prolific Tweeter, “seemed to have strong opinions about everything, and wrote about almost everything in his world and his time,”1 with topics ranging from economics, politics and history to space travel.2 While Defoe wrote over 500 books, pamphlets, addresses and letters in his lifetime, Crusoe became his most well-known and well-read work.3 Crusoe was a major hit right from its first printing, it was so well received that Defoe quickly produced a sequel within only a few months after publication of the first. -

Parallel Lives : Five Victorian Marriages Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PARALLEL LIVES : FIVE VICTORIAN MARRIAGES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Phyllis Rose | 360 pages | 19 Mar 2020 | Daunt Books | 9781911547525 | English | London, United Kingdom Parallel Lives : Five Victorian Marriages PDF Book How to Write a Research Paper on Parallel Lives This page is designed to show you how to write a research project on the topic you see here. In the 19th century, marriage was a site of trenchant structural inequality. Really irrecoverably hate him and his work. The book reveals the social difficulties faced by intelligent women in an environment in which female scholarship and achievement was discouraged. Related Articles. Lieutenant Nun. The new Daunt edition seeks to remedy that by emphasising its relevance to the 21st century. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them. If you like reading college dissertations you might find this book interesting. Any Condition Any Condition. I felt the author inserted a lot of personal opinion into the stories, but I didn't necessarily mind this; it's just helpful to know th "None behave with a greater appearance of guilt than people who are convinced of their own virtue. See all 25 - All listings for this product. I don't share her general cynicism towards marriage, but I subscribe wholeheartedly towards her definition of parallel living and the desire to normalize a certain, inquisitive level of gossip. Biography books. All the famous people I had known about as great thinkers and authors came to life in this text. The body chapters are full of details of the different forms marriages can take, and of those I loved the George Eliot and George Henry Lewes chapter best. -

Radiolovefest

BAM 2017 Winter/Spring Season #RadioLoveFest Brooklyn Academy of Music New York Public Radio* Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board Cynthia King Vance, Chair, Board of Trustees William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board John S. Rose, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Katy Clark, President Susan Rebell Solomon, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Mayo Stuntz, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Laura R. Walker, President & CEO *As of February 1, 2017 BAM and WNYC present RadioLoveFest Produced by BAM and WNYC February 7—11 LIVE PERFORMANCES Ira Glass, Monica Bill Barnes & Anna Bass: Three Acts, Two Dancers, One Radio Host: All the Things We Couldn’t Do on the Road Feb 7, 8pm; Feb 8, 7pm & 9:30pm, HT The Moth at BAM—Reckless: Stories of Falling Hard and Fast, Feb 9, 7:30pm, HT Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me®, National Public Radio, Feb 9, 7:30pm, OH Jon Favreau, Jon Lovett, and Tommy Vietor, Feb 10, 7:30pm, HT Snap Judgment LIVE!, Feb 10, 7:30pm, OH Bullseye Comedy Night, Feb 11, 7:30pm, HT BAMCAFÉ LIVE Curated by Terrance McKnight Braxton Cook, Feb 10, 9:30pm, BC, free Gerardo Contino y Los Habaneros, Feb 11, 9pm, BC, free Season Sponsor: Leadership support provided by The Joseph S. and Diane H. Steinberg Charitable Trust. Delta Air Lines is the Official Airline of RadioLoveFest. Audible is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. VENUE KEY BC=BAMcafé Forest City Ratner Companies is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. BRC=BAM Rose Cinemas Williams is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

The Castaway Medyett Goodridge's Unvarnished Tale Of

Document generated on 09/29/2021 11:10 p.m. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies The Castaway Medyett Goodridge’s Unvarnished Tale of Shipwreck and Desolation Print Culture and Settler Colonialism in Newfoundland Stephen Crocker Volume 32, Number 2, Fall 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds32_2art06 See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 1719-1726 (print) 1715-1430 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Crocker, S. (2017). The Castaway Medyett Goodridge’s Unvarnished Tale of Shipwreck and Desolation: Print Culture and Settler Colonialism in Newfoundland. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 32(2), 429–460. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2014 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ The Castaway Medyett Goodridge’s Unvarnished Tale of Shipwreck and Desolation: Print Culture and Settler Colonialism in Newfoundland Stephen Crocker 1. Narrative of a Voyage to the South Seas, and the Shipwreck of the Prin- cess of Wales Cutter: with an Account of Two Years’ Residence on an Un- inhabited Island1 is an obscure castaway narrative from 1838 with a special relation to Newfoundland. It is one of countless tales of ship- wreck and castaways that circulated in the popular “transatlantic lit- erature” of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.2 Through seven editions and reprints, it provided its author, Medyett Goodridge, a source of income in his late years. -

Heyward, Dorothy Papers, 180.00

Dorothy Heyward papers, ca. 1850-1976 (bulk 1918-1961) SCHS 180.00 Creator: Heyward, Dorothy, 1890-1961. Description: 18 linear ft. Biographical/Historical note: Playwright and novelist. The daughter of Herman Luyties Kuhns (b. 1855) and Dora Virginia Hartzell, Dorothy Hartzell Kuhns was born in Wooster, Ohio. Dorothy studied playwrighting at Harvard University, and as a fellow of George Pierce Baker's Workshop 47 she spent a summer's residency at the MacDowell Colony, an artists' retreat in New Hampshire, where she met South Carolina author DuBose Heyward (1885-1940). They married in September 1923. Their only child was Jenifer DuBose Heyward (later Mrs. Jenifer Wood, 1930-1984), who became a ballet dancer and made her home in New York, N.Y. Dorothy collaborated with her husband to produce a dramatic version of his novel "Porgy." The play became the libretto for the opera "Porgy & Bess" (first produced in 1935) by DuBose Heyward and George and Ira Gershwin. She also collaborated with her husband to produce "Mamba's Daughters," a play based on DuBose Heyward's novel by the same name. In 1940 Dorothy Heyward succeeded her late husband as the resident dramatist at the Dock Street Theater (Charleston, S.C.). In the years following his death she continued to write and published a number of works including the plays "South Pacific" (1943) and "Set My People Free" (1948, the story of the Denmark Vesey slave insurrection), as well as the libretto for the children's opera "Babar the Elephant" (1953). Earlier works by Dorothy Heyward include the plays "Love in a Cupboard" (1925), "Jonica" (1930), and "Cinderelative" (1930, in collaboration with Dorothy DeJagers), and the novels "Three-a-Day" (1930) and "The Pulitzer Prize Murders" (1932). -

Reciprocity in Experimental Writing, Hypertext Fiction, and Video Games

UNDERSTANDING INTERACTIVE FICTIONS AS A CONTINUUM: RECIPROCITY IN EXPERIMENTAL WRITING, HYPERTEXT FICTION, AND VIDEO GAMES. A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 ELIZABETH BURGESS SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES 2 LIST OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Declaration 4 Copyright Statement 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Chapter One: Materially Experimental Writing 30 1.1 Introduction.........................................................................................30 1.2 Context: metafiction, realism, telling the truth, and public opinion....36 1.3 Randomness, political implications, and potentiality..........................53 1.4 Instructions..........................................................................................69 1.41 Hopscotch...................................................................................69 1.42 The Unfortunates........................................................................83 1.43 Composition No. 1......................................................................87 1.5 Conclusion...........................................................................................94 Chapter Two: Hypertext Fiction 96 2.1 Introduction.........................................................................................96 2.2 Hypertexts: books that don’t end?......................................................102 2.3 Footnotes and telling the truth............................................................119 -

Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages, 2010, 336 Pages, Phyllis Rose, 0307761509, 9780307761507, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2010

Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages, 2010, 336 pages, Phyllis Rose, 0307761509, 9780307761507, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2010 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1Sld3Ps http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=Parallel+Lives%3A+Five+Victorian+Marriages In her study of the married couple as the smallest political unit, Phyllis Rose uses as examples the marriages of five Victorian writers who wrote about their own lives with unusual candor.From the Trade Paperback edition. DOWNLOAD http://is.gd/pT7NNZ http://bit.ly/1nY2Cwq Unwanted Wife A Defence of Mrs. Charles Dickens, Dorothy Phoebe Ansle, 1963, Novelists, English, 238 pages. Dickens and Education , Philip Collins, 1963, Education, 258 pages. Appendix contains chronological table of Dicken's main educational activities and writings.. Charles Dickens a literary life, Grahame Smith, 1996, Literary Criticism, 190 pages. George Eliot, the woman , Margaret Crompton, 1960, Women novelists, English, 214 pages. George Eliot's Originals and Contemporaries Essays in Victorian Literary History and Biography, Gordon Sherman Haight, 1992, Literary Criticism, 240 pages. Eminent Victorian scholar Gordon Haight's newly collected essays on George Eliot and her literary tradition.. The Dickens Circle A Narrative of the Novelist's Friendships, James William Thomas Ley, 1919, Literary Criticism, 424 pages. An intimate portrait of Charles Dickens, his family & friends. Interesting sidelights on an author who is now enjoying a great revival.. The selected letters of Charles Dickens , Charles Dickens, 1960, Biography & Autobiography, 293 pages. Arranged in six sections, with an introductory preface to each of these letters grouped to follow the main events of Dickens' life and career.. Reason Over Passion Harriet Martineau and the Victorian Novel, Valerie Sanders, 1986, Biography & Autobiography, 236 pages. -

PAPERS: the ASSOCIATED NEGRO PRESS, 1918-1967 Part Three Subject Files on Black Americans, 1918-1967

THE CLAUDE A. BARNETT PAPERS: THE ASSOCIATED NEGRO PRESS, 1918-1967 Part Three Subject Files on Black Americans, 1918-1967 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES: Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections August Meier and Elliott Rudwick General Editors THE CLAUDE A. BARNETT PAPERS: The Associated Negro Press, 1918-1967 Part Three Subject Files on Black Americans, 1918-1967 THE CLAUDE A. BARNETT PAPERS: The Associated Negro Press, 1918-1967 Part Three Subject Files on Black Americans, 1918-1967 Seri es A: Agriculture, 1923-1966 Seri es B: Colleges and Universities, 1918-1966 Seri es C: Economic Conditions, 1918-1966 Ser es D: Entertainers, Artists, and Authors, 1928-1965 Ser es E: Medicine, 1927-1965 Ser es F: Military, 1925-1965 Seri es G: Philanthropic and Social Organizations, 1925-1966 Seri es H: Politics and Law, 1920-1966 Seri es I: Race Relations, 1923-1965 Seri es J: Religion, 1924-1966 Seri es K: Claude A. Barnett, Personal and Financial, 1920-1967 Microfilmed from the holdings of the Chicago Historical Society Edited by August Meier and Elliott Rudwick A Microfilm Project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA, INC. 44 North Market Street • Frederick, Maryland 21701 NOTE ON SELECTIONS Portions of the Claude A. Barnett papers at the Archives and Manuscripts Depart- ment of the Chicago Historical Society do not appear in this microfilm edition. The editors chose not to include African and other foreign relations materials and to film only the American categories of the Barnett papers that hold the greatest potential research value. Materials of negligible or specialized research interest that were not microfilmed include some pamphlets, some categories composed entirely of news- clippings, partial sets of minutes of institutions which Barnett served as a board member, a small group of materials that are closed to researchers at present, and routine financial records. -

Spoleto Festival USA Announces Live Broadcast of Opera Porgy and Bess in Marion Square Monday, May 30 at 7:30Pm

SPOLETO FESTIVAL USA NEWS RELEASE Press Contacts: Jennifer Scott, Director of Marketing & Public Relations 843.720.1137 office | 702.510.4363 cell [email protected] Jessie Bagley, Marketing & Public Relations Manager 843.720.1136 office | 843.696.6012 cell [email protected] Spoleto Festival USA Announces Live Broadcast of Opera Porgy and Bess in Marion Square Monday, May 30 at 7:30pm Broadcast to be screened outdoors at West Ashley High School Tuesday, May 31 at 7:30pm Events free to attend and open to the public Presented in association with Piccolo Spoleto Festival May 4, 2016 (CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA)—Festival General Director Nigel Redden today announced a live broadcast of opera Porgy and Bess onto a jumbotron screen in Marion Square on Monday, May 30. Thanks to generous sponsorship by Wells Fargo, the simulcast will be open to the public and free to attend. The live broadcast of the performance taking place at the Charleston Gaillard Center will start at 7:30pm. The following night, Tuesday, May 31, the performance will be shown on a jumbotron screen at the West Ashley High School practice field at 7:30pm. This screening will also be free to attend. Presented in association with Piccolo Spoleto Festival and the City of Charleston Office of Cultural Affairs, these events will significantly expand the audience for the highly-anticipated production that is part of the Festival’s 40th season. Additional sponsorship for this event has been provided by the Charleston Area Convention and Visitors Bureau, BET Networks/Viacom, and LiftOne. “Last year, when I ran for mayor, I said that one of our goals should be to improve our citizens’ quality of life by making the arts more accessible to more residents in more areas of our city. -

CURRICULUM VITAE PAUL B. ARMSTRONG Department Of

CURRICULUM VITAE PAUL B. ARMSTRONG Department of English Brown University Providence, RI 02912 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION AND DEGREES Ph.D., Stanford University, Modern Thought and Literature, 1977 A.M., Stanford University, Modern Thought and Literature, 1974 A.B., summa cum laude, Harvard College, History and Literature, 1971 PUBLICATIONS Books: How Literature Plays with the Brain: The Neuroscience of Reading and Art (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2013), xv + 221 pp. A Norton Critical Edition of Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness, 4th Edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), xix + 516 pp. [electronic edition published 2012] Play and the Politics of Reading: The Social Uses of Modernist Form (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ. Press, 2005), xv + 207 pp. A Norton Critical Edition of E. M. Forster, Howards End (New York: W. W. Norton, 1998), xii + 473 pp. Conflicting Readings: Variety and Validity in Interpretation (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1990), xiv + 195 pp. [Spanish translation: Lecturas en Conflicto: Validez y Variedad en la Interpretación, trans. Marcela Pineda Camacho (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1992)] [Excerpt reprinted in the Norton Critical Edition of The Turn of the Screw, ed. Deborah Esch and Jonathan Warren, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999), 245-54] القراءات المتصارعة: التنوع والمصداقية :Arabic translation, with new preface and appendixes] trans. Falah R. Jassim (Beirut, Lebanon: Dar Al Kitab Al Jadid [New Book في التأويل Press], 2009)] The Challenge of Bewilderment: Understanding and Representation in James, Conrad, and Ford Paul B. Armstrong, Curriculum Vitae 2 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ.