COMMENTS on GNATHIID ISOPODS D. B. Cadien & L. Haney (CSDLAC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Diversity of Marine Isopods (Except Asellota and Crustacean Symbionts)

Collection Review Global Diversity of Marine Isopods (Except Asellota and Crustacean Symbionts) Gary C. B. Poore1*, Niel L. Bruce2,3 1 Museum Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2 Museum of Tropical Queensland and School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia, 3 Department of Zoology, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park, South Africa known from the supralittoral and intertidal to depths in excess of Abstract: The crustacean order Isopoda (excluding six kilometres. Isopods are a highly diverse group of crustaceans, Asellota, crustacean symbionts and freshwater taxa) with more than 10,300 species known to date, approximately comprise 3154 described marine species in 379 genera 6,250 of these being marine or estuarine. In the groups under in 37 families according to the WoRMS catalogue. The discussion here (about half the species) the vast majority of species history of taxonomic discovery over the last two centuries are known from depths of less than 1000 metres. is reviewed. Although a well defined order with the Peracarida, their relationship to other orders is not yet The Isopoda is one of the orders of peracarid crustaceans, that resolved but systematics of the major subordinal taxa is is, those that brood their young in a marsupium under the body. relatively well understood. Isopods range in size from less They are uniquely defined within Peracarida by the combination than 1 mm to Bathynomus giganteus at 365 mm long. of one pair of uropods attached to the pleotelson and pereopods of They inhabit all marine habitats down to 7280 m depth only one branch. Marine isopods are arguably the most but with few doubtful exceptions species have restricted morphologically diverse order of all the Crustacea. -

Redalyc.Isopods (Isopoda: Aegidae, Cymothoidae, Gnathiidae)

Revista de Biología Tropical ISSN: 0034-7744 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Bunkley-Williams, Lucy; Williams, Jr., Ernest H.; Bashirullah, Abul K.M. Isopods (Isopoda: Aegidae, Cymothoidae, Gnathiidae) associated with Venezuelan marine fishes (Elasmobranchii, Actinopterygii) Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 54, núm. 3, diciembre, 2006, pp. 175-188 Universidad de Costa Rica San Pedro de Montes de Oca, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44920193024 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Isopods (Isopoda: Aegidae, Cymothoidae, Gnathiidae) associated with Venezuelan marine fishes (Elasmobranchii, Actinopterygii) Lucy Bunkley-Williams,1 Ernest H. Williams, Jr.2 & Abul K.M. Bashirullah3 1 Caribbean Aquatic Animal Health Project, Department of Biology, University of Puerto Rico, P.O. Box 9012, Mayagüez, PR 00861, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Marine Sciences, University of Puerto Rico, P.O. Box 908, Lajas, Puerto Rico 00667, USA; ewil- [email protected] 3 Instituto Oceanografico de Venezuela, Universidad de Oriente, Cumaná, Venezuela. Author for Correspondence: LBW, address as above. Telephone: 1 (787) 832-4040 x 3900 or 265-3837 (Administrative Office), x 3936, 3937 (Research Labs), x 3929 (Office); Fax: 1-787-834-3673; [email protected] Received 01-VI-2006. Corrected 02-X-2006. Accepted 13-X-2006. Abstract: The parasitic isopod fauna of fishes in the southern Caribbean is poorly known. In examinations of 12 639 specimens of 187 species of Venezuelan fishes, the authors found 10 species in three families of isopods (Gnathiids, Gnathia spp. -

Host DNA Integrity Within Blood Meals of Hematophagous Larval Gnathiid Isopods (Crustacea, Isopoda, Gnathiidae) Gina C

Hendrick et al. Parasites Vectors (2019) 12:316 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3567-8 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Host DNA integrity within blood meals of hematophagous larval gnathiid isopods (Crustacea, Isopoda, Gnathiidae) Gina C. Hendrick1,2, Maureen C. Dolan1,2, Tanja McKay1 and Paul C. Sikkel1* Abstract Background: Juvenile gnathiid isopods are common ectoparasites of marine fshes. Each of the three juvenile stages briefy attach to a host to obtain a blood meal but spend most of their time living in the substrate, thus making it difcult to determine patterns of host exploitation. Sequencing of host blood meals from wild-caught specimens is a promising tool to determine host identity. Although established protocols for this approach exist, certain challenges must be overcome when samples are subjected to typical feld conditions that may contribute to DNA degradation. The goal of this study was to address a key methodological issue associated with molecular-based host identifcation from free-living, blood-engorged gnathiid isopods—the degradation of host DNA within blood meals. Here we have assessed the length of time host DNA within gnathiid blood meals can remain viable for positive host identifcation. Methods: Juvenile gnathiids were allowed to feed on fsh of known species and subsets were preserved at 4-h intervals over 24 h and then every 24 h up to 5 days post-feeding. Host DNA extracted from gnathiid blood meals was sequenced to validate the integrity of host DNA at each time interval. DNA was also extracted from blood meals of wild-fed gnathiids for comparison. -

A New Species of the Gnathiid Isopod, Gnathia Teruyukiae (Crustacea: Malacostraca), from Japan, Parasitizing Elasmobranch Fish

Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Ser. A, Suppl. 5, pp. 41–51, February 21, 2011 A New Species of the Gnathiid Isopod, Gnathia teruyukiae (Crustacea: Malacostraca), from Japan, Parasitizing Elasmobranch Fish Yuzo Ota Graduate School of Engineering and Science, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Okinawa, 903–0213 Japan. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of gnathiid isopod, Gnathia teruyukiae, is described on the basis of lab- oratory reared material moulted from larvae, which parasitized elasmobranch fish caught from off Okinawa Island, Ryukyu Islands. Praniza larvae are also described. It is morphologically most sim- ilar to G. meticola Holdich and Harrison, 1980, but differs in the body length, the mandible length, and the structure of the mouthparts. Key words : ectoparasite, gnathiids, Ryukyu Archipelago, larval morphology. The family Gnathiidae Leach, 1814, contains 2008; Coetzee et al., 2008, 2009; Ferreira et al., over 190 species belonging to 12 genera (Had- 2009). I also have studied gnathiid larvae ec- field et al., 2008). Members of the family are dis- toparasites of elasmobranchs caught by commer- tributed world-wide, and found in intertidal zone cial fisheries in waters around the Ryukyu Archi- to abyssal depths of 4000 m (Camp, 1988; Cohen pelago, southwestern Japan (Ota and Hirose, and Poore, 1994). From Japanese and adjacent 2009a, 2009b). In this paper, a new species, waters, about 30 species in six genera have been Gnathia teruyukiae, is described on the basis of recorded (Shimomura and Tanaka, 2008; Ota and these laboratory reared adult specimens. Hirose, 2009b). Gnathiid isopods exhibit great morphological Materials and Methods differences between the larva, adult male, and adult female (Mouchet, 1928), and undergo a Between April 2004 and September 2009, biphasic life cycle involving parasitic larvae and elasmobranch hosts caught in Nakagusuku Bay non-feeding adults. -

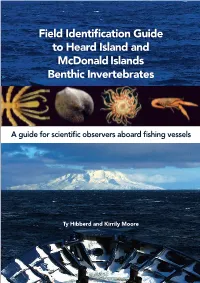

Benthic Field Guide 5.5.Indb

Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates Invertebrates Benthic Moore Islands Kirrily and McDonald and Hibberd Ty Island Heard to Guide cation Identifi Field Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates A guide for scientifi c observers aboard fi shing vessels Little is known about the deep sea benthic invertebrate diversity in the territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI). In an initiative to help further our understanding, invertebrate surveys over the past seven years have now revealed more than 500 species, many of which are endemic. This is an essential reference guide to these species. Illustrated with hundreds of representative photographs, it includes brief narratives on the biology and ecology of the major taxonomic groups and characteristic features of common species. It is primarily aimed at scientifi c observers, and is intended to be used as both a training tool prior to deployment at-sea, and for use in making accurate identifi cations of invertebrate by catch when operating in the HIMI region. Many of the featured organisms are also found throughout the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean, the guide therefore having national appeal. Ty Hibberd and Kirrily Moore Australian Antarctic Division Fisheries Research and Development Corporation covers2.indd 113 11/8/09 2:55:44 PM Author: Hibberd, Ty. Title: Field identification guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands benthic invertebrates : a guide for scientific observers aboard fishing vessels / Ty Hibberd, Kirrily Moore. Edition: 1st ed. ISBN: 9781876934156 (pbk.) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Benthic animals—Heard Island (Heard and McDonald Islands)--Identification. -

Angelika Brandt

PUBLICATION LIST: DR. ANGELIKA BRANDT Research papers (peer reviewed) Wägele, J. W. & Brandt, A. (1985): New West Atlantic localities for the stygobiont paranthurid Curassanthura (Crustacea, Isopoda, Anthuridea) with description of C. bermudensis n. sp. Bijdr. tot de Dierkd. 55 (2): 324- 330. Brandt, A. (1988):k Morphology and ultrastructure of the sensory spine, a presumed mechanoreceptor of the isopod Sphaeroma hookeri (Crustacea, Isopoda) and remarks on similar spines in other peracarids. J. Morphol. 198: 219-229. Brandt, A. & Wägele, J. W. (1988): Antarbbbcturus bovinus n. sp., a new Weddell Sea isopod of the family Arcturidae (Isopoda, Valvifera) Polar Biology 8: 411-419. Wägele, J. W. & Brandt, A. (1988): Protognathia n. gen. bathypelagica (Schultz, 1978) rediscovered in the Weddell Sea: A missing link between the Gnathiidae and the Cirolanidae (Crustacea, Isopoda). Polar Biology 8: 359-365. Brandt, A. & Wägele, J. W. (1989): Redescriptions of Cymodocella tubicauda Pfeffer, 1878 and Exosphaeroma gigas (Leach, 1818) (Crustacea, Isopoda, Sphaeromatidae). Antarctic Science 1(3): 205-214. Brandt, A. & Wägele, J. W. (1990): Redescription of Pseudidothea scutata (Stephensen, 1947) (Crustacea, Isopoda, Valvifera) and adaptations to a microphagous nutrition. Crustaceana 58 (1): 97-105. Brandt, A. & Wägele, J. W. (1990): Isopoda (Asseln). In: Sieg, J. & Wägele, J. W. (Hrsg.) Fauna der Antarktis. Verlag Paul Parey, Berlin und Hamburg, S. 152-160. Brandt, A. (1990): The Deep Sea Genus Echinozone Sars, 1897 and its Occurrence on the Continental shelf of Antarctica (Ilyarachnidae, Munnopsidae, Isopoda, Crustacea). Antarctic Science 2(3): 215-219. Brandt, A. (1991): Revision of the Acanthaspididae Menzies, 1962 (Asellota, Isopoda, Crustacea). Journal of the Linnean Society of London 102: 203-252. -

Cleaner Shrimp As Biocontrols in Aquaculture

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following work: Vaughan, David Brendan (2018) Cleaner shrimp as biocontrols in aquaculture. PhD Thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: https://doi.org/10.25903/5c3d4447d7836 Copyright © 2018 David Brendan Vaughan The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owners of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please email [email protected] Cleaner shrimp as biocontrols in aquaculture Thesis submitted by David Brendan Vaughan BSc (Hons.), MSc, Pr.Sci.Nat In fulfilment of the requirements for Doctorate of Philosophy (Science) College of Science and Engineering James Cook University, Australia [31 August, 2018] Original illustration of Pseudanthias squamipinnis being cleaned by Lysmata amboinensis by D. B. Vaughan, pen-and-ink Scholarship during candidature Peer reviewed publications during candidature: 1. Vaughan, D.B., Grutter, A.S., and Hutson, K.S. (2018, in press). Cleaner shrimp are a sustainable option to treat parasitic disease in farmed fish. Scientific Reports [IF = 4.122]. 2. Vaughan, D.B., Grutter, A.S., and Hutson, K.S. (2018, in press). Cleaner shrimp remove parasite eggs on fish cages. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, DOI:10.3354/aei00280 [IF = 2.900]. 3. Vaughan, D.B., Grutter, A.S., Ferguson, H.W., Jones, R., and Hutson, K.S. (2018). Cleaner shrimp are true cleaners of injured fish. Marine Biology 164: 118, DOI:10.1007/s00227-018-3379-y [IF = 2.391]. 4. Trujillo-González, A., Becker, J., Vaughan, D.B., and Hutson, K.S. -

Isopods (Isopoda: Aegidae, Cymothoidae, Gnathiidae) Associated with Venezuelan Marine Fishes (Elasmobranchii, Actinopterygii)

Isopods (Isopoda: Aegidae, Cymothoidae, Gnathiidae) associated with Venezuelan marine fishes (Elasmobranchii, Actinopterygii) Lucy Bunkley-Williams,1 Ernest H. Williams, Jr.2 & Abul K.M. Bashirullah3 1 Caribbean Aquatic Animal Health Project, Department of Biology, University of Puerto Rico, P.O. Box 9012, Mayagüez, PR 00861, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Marine Sciences, University of Puerto Rico, P.O. Box 908, Lajas, Puerto Rico 00667, USA; ewil- [email protected] 3 Instituto Oceanografico de Venezuela, Universidad de Oriente, Cumaná, Venezuela. Author for Correspondence: LBW, address as above. Telephone: 1 (787) 832-4040 x 3900 or 265-3837 (Administrative Office), x 3936, 3937 (Research Labs), x 3929 (Office); Fax: 1-787-834-3673; [email protected] Received 01-VI-2006. Corrected 02-X-2006. Accepted 13-X-2006. Abstract: The parasitic isopod fauna of fishes in the southern Caribbean is poorly known. In examinations of 12 639 specimens of 187 species of Venezuelan fishes, the authors found 10 species in three families of isopods (Gnathiids, Gnathia spp. from Diplectrum radiale*, Heteropriacanthus cruentatus*, Orthopristis ruber* and Trachinotus carolinus*; two aegids, Rocinela signata from Dasyatis guttata*, H. cruentatus*, Haemulon auro- lineatum*, H. steindachneri* and O. ruber; and Rocinela sp. from Epinephelus flavolimbatus*; five cymothoids: Anilocra haemuli from Haemulon boschmae*, H. flavolineatum* and H. steindachneri*; Anilocra cf haemuli from Heteropriacanthus cruentatus*; Haemulon bonariense*, O. ruber*, Cymothoa excisa in H. cruentatus*; Cymothoa oestrum in Chloroscombrus chrysurus, H. cruentatus* and Priacanthus arenatus; Cymothoa sp. in O. ruber; Livoneca sp. from H. cruentatus*; and Nerocila fluviatilis from H. cruentatus* and P. arenatus*). The Rocinela sp. and A. -

Ostrovsky Et 2016-Biological R

Matrotrophy and placentation in invertebrates: a new paradigm Andrew Ostrovsky, Scott Lidgard, Dennis Gordon, Thomas Schwaha, Grigory Genikhovich, Alexander Ereskovsky To cite this version: Andrew Ostrovsky, Scott Lidgard, Dennis Gordon, Thomas Schwaha, Grigory Genikhovich, et al.. Matrotrophy and placentation in invertebrates: a new paradigm. Biological Reviews, Wiley, 2016, 91 (3), pp.673-711. 10.1111/brv.12189. hal-01456323 HAL Id: hal-01456323 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01456323 Submitted on 4 Feb 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Biol. Rev. (2016), 91, pp. 673–711. 673 doi: 10.1111/brv.12189 Matrotrophy and placentation in invertebrates: a new paradigm Andrew N. Ostrovsky1,2,∗, Scott Lidgard3, Dennis P. Gordon4, Thomas Schwaha5, Grigory Genikhovich6 and Alexander V. Ereskovsky7,8 1Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Universitetskaja nab. 7/9, 199034, Saint Petersburg, Russia 2Department of Palaeontology, Faculty of Earth Sciences, Geography and Astronomy, Geozentrum, -

New Record of Two Cymothoid Isopods(Crustacea: Malacostraca: Isopoda) from South Korea

Journal of Species Research 5(3):313317, 2016 New record of two cymothoid isopods (Crustacea: Malacostraca: Isopoda) from South Korea JiHun Song and GiSik Min* Department of Biological Sciences, Inha University, Incheon 22212, Republic of Korea *Correspondent: [email protected] Two marine isopods, Elaphognathia sugashimaensis (Nunomura, 1981) and Metacirolana shijikiensis Nunomura, 2008, have been reported for the first time in South Korea. Specimens of E. sugashimaensis and M. shijikiensis were collected using light traps from Yeongdeokgun and Gageodo Island in South Korea, respectively. The genera Elaphognathia Monod, 1926 and Metacirolana Kussakin, 1979 are new to South Korea. In this paper, we provide descriptions of diagnostic characteristics and illustrations of their morphologies. Additionally, the partial sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) of two species are provided as molecular characteristics. Keywords: CO1, Elaphognathia sugashimaensis, Isopoda, Metacirolana shijikiensis, South Korea Ⓒ 2016 National Institute of Biological Resources DOI:10.12651/JSR.2016.5.3.313 INTRODUCTION Herein, we provide descriptions of the diagnostic characteristics and illustrations of morphologies of two Recently, the number of newly recorded isopod spe species. In addition, the partial sequences of CO1 of cies from South Korea has increased gradually: two these species are provided as molecular characteristics. new species and five unrecorded species (Song and Min, 2015a; 2015b; 2015c). In this paper, we reported two un recorded isopod species: Elaphognathia sugashimaensis MATERIALS AND METHODS (Nunomura, 1981) and Metacirolana shijikiensis Nuno mura, 2008. Sample collection The genus Elaphognathia Monod, 1926 (Isopoda: Specimens of E. sugashimaensis and M. shijikiensis Cymothoida: Gnathiidae), is one of 12 genera that be were collected using light traps from Yeongdeokgun long to the family Gnathiidae Leach, 1814. -

Global Diversity of Fish Parasitic Isopod Crustaceans of the Family

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Review Global diversity of fish parasitic isopod crustaceans of the family Cymothoidae ⇑ Nico J. Smit a, , Niel L. Bruce a,b, Kerry A. Hadfield a a Water Research Group (Ecology), Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North West University, Potchefstroom Campus, Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa b Museum of Tropical Queensland, Queensland Museum and School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, 70–102 Flinders Street, Townsville 4810, Australia article info abstract Article history: Of the 95 known families of Isopoda only a few are parasitic namely, Bopyridae, Cryptoniscidae, Received 7 February 2014 Cymothoidae, Dajidae, Entoniscidae, Gnathiidae and Tridentellidae. Representatives from the family Revised 19 March 2014 Cymothoidae are obligate parasites of both marine and freshwater fishes and there are currently 40 Accepted 20 March 2014 recognised cymothoid genera worldwide. These isopods are large (>6 mm) parasites, thus easy to observe Available online xxxx and collect, yet many aspects of their biodiversity and biology are still unknown. They are widely distributed around the world and occur in many different habitats, but mostly in shallow waters in Keywords: tropical or subtropical areas. A number of adaptations to an obligatory parasitic existence have been Isopoda observed, such as the body shape, which is influenced by the attachment site on the host. Cymothoids Biodiversity Parasites generally have a long, slender body tapering towards the ends and the efficient contour of the body offers Cymothoidae minimum resistance to the water flow and can withstand the forces of this particular habitat. -

Comparison of Sampling Methodologies and Estimation of Population Parameters for a Temporary fish Ectoparasite

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 5 (2016) 145e157 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Comparison of sampling methodologies and estimation of population parameters for a temporary fish ectoparasite * J.M. Artim a, P.C. Sikkel a, b, a Department of Biological Sciences and Environmental Sciences Program, Arkansas State University, State University, AR 72467, USA b Water Research Group, Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa article info abstract Article history: Characterizing spatio-temporal variation in the density of organisms in a community is a crucial part of Received 26 March 2016 ecological study. However, doing so for small, motile, cryptic species presents multiple challenges, Received in revised form especially where multiple life history stages are involved. Gnathiid isopods are ecologically important 19 May 2016 marine ectoparasites, micropredators that live in substrate for most of their lives, emerging only once Accepted 20 May 2016 during each juvenile stage to feed on fish blood. Many gnathiid species are nocturnal and most have distinct substrate preferences. Studies of gnathiid use of habitat, exploitation of hosts, and population Keywords: dynamics have used various trap designs to estimate rates of gnathiid emergence, study sensory ecology, Gnathiid Tick and identify host susceptibility. In the studies reported here, we compare and contrast the performance fi Mosquito of emergence, sh-baited and light trap designs, outline the key features of these traps, and determine Micropredator some life cycle parameters derived from trap counts for the Eastern Caribbean coral-reef gnathiid, Vector Gnathia marleyi.