Land Ownership: Caste and Economic Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

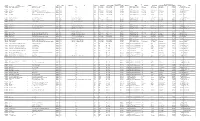

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

Castes and Caste Relationships

Chapter 4 Castes and Caste Relationships Introduction In order to understand the agrarian system in any Indian local community it is necessary to understand the workings of the caste system, since caste patterns much social and economic behaviour. The major responses to the uncertain environment of western Rajasthan involve utilising a wide variety of resources, either by spreading risks within the agro-pastoral economy, by moving into other physical regions (through nomadism) or by tapping in to the national economy, through civil service, military service or other employment. In this chapter I aim to show how tapping in to diverse resource levels can be facilitated by some aspects of caste organisation. To a certain extent members of different castes have different strategies consonant with their economic status and with organisational features of their caste. One aspect of this is that the higher castes, which constitute an upper class at the village level, are able to utilise alternative resources more easily than the lower castes, because the options are more restricted for those castes which own little land. This aspect will be raised in this chapter and developed later. I wish to emphasise that the use of the term 'class' in this context refers to a local level class structure defined in terms of economic criteria (essentially land ownership). All of the people in Hinganiya, and most of the people throughout the village cluster, would rank very low in a class system defined nationally or even on a district basis. While the differences loom large on a local level, they are relatively minor in the wider context. -

Haryana Government Gazette

Haryana Government Gazette EXTRAORDINARY Published by Authority © Govt. of Haryana No. 21-2021/Ext.] CHANDIGARH, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2021 (MAGHA 20, 1942 SAKA) HARYANA GOVERNMENT PERSONNEL DEPARTMENT Notification The 9th February, 2021 No. 42/1/2018-5SII – In pursuance of the Rule 11(1) of the Haryana Civil Services (Executive Branch) Rules, 2008 and in supersession of Notification No. 42/1/95-5SII, dated 6th November, 2008, the Governor of Haryana is pleased to order that the syllabi for the Preliminary Examination as well as Main Written Examination for the posts of Haryana Civil Service (Executive Branch) and Allied Services shall be as under:- SYLLABI FOR THE PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION 1. GENERAL STUDIES General Science. Current events of national and international importance. History of India and Indian National Movement. Indian and World Geography. Indian Culture, Indian Polity and Indian Economy. General Mental Ability. Haryana-Economy and people. Social, economic and culture institutions and language of Haryana. Questions on General Science will cover general appreciation and understanding of science including matters of everyday observation and experience, as may be expected of a well educated person who has not made a special study of any particular scientific discipline. In current events, knowledge of significant national and international events will be tested. In History of India, emphasis will be on broad general understanding of the subject in its social, economic and political aspects. Questions on the Indian National Movement will relate to the nature and character of the nineteenth century resurgence, growth of nationalism and attainment of Independence. In Geography, emphasis will be on Geography of India. -

Marking Scheme Geography

C. B. S. E. SAMPLE QUESTION PAPER (2020-21) MARKING SCHEME GEOGRAPHY (029) CLASS 12 Time: 3hours Max. Marks 70 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS- i. Question paper is divided into 3 Sections – A, B and C. ii. In Section A Question numbers 1 to15 are Objective type Multiple choice questions carrying 1 mark each. Attempt any 14 questions. Write the correct answer only in your answer sheets. iii. In Section B, Question numbers 16 and 17 are Short Source Based and Graph Based questions respectively carrying 3 marks each. Answer any three questions out of 4. Each of these sub-questions carry 1 mark . iv. In Section C, Question numbers 18 to 22 are short answer questions carrying 3 marks each. Answers to these questions should not exceed 60-80 words. v. In Section C, Question numbers 23 to 27 are long answer questions carrying 5 marks each. Answers to these questions should not exceed 120-150 words. vi. Question numbers 28 and 29 are related to location and labeling and Identification of geographical features on maps respectively, carrying 5 marks each. vii. Outline map of India and World provided to you must be attached with your answer book. viii. Use of template or stencils for drawing outline maps is allowed. SECTION A Q1 Fill in the blanks- 1 ________________ and _______________ densities should be found out, in order to get a better insight into the human-land ratio: ANSWER – c) Physiological and Agricultural 1 Q2 Arrange the following approaches in a correct order according to their 1 development 1. Spatial organization 2. -

Water Pressure

By Fen Montaigne Photographs by Peter Essick How can such a wet planet be so short on clean fresh water? The latest installment in the "Challenges for Humanity" series plumbs the problem. Rajendra Singh came to the village, bringing with him the promise of water. If ever a place needed moisture, this hamlet in the desiccated Indian state of Rajasthan was it. Always a dry spot, Rajasthan had suffered several years of drought, leaving remote villages like Goratalai with barely enough water to quench the thirst of their inhabitants. Farm plots had shriveled, and men had fled to the cities seeking work, leaving those behind to subsist on roti, corn, and chili paste. Desperate villagers appealed to a local aristocratic family, who in turn contacted Singh, a man renowned across western India for his ability to use traditional methods of capturing monsoon rains to supply water year-round. Singh arrived in Goratalai on a warm ankle bracelets jangling as they walked. February morning. The sky was robin's egg After a few minutes Singh—dressed in a blue, the same color it had been since light-golden blouse that fell to his knees and August when, everyone recalled, the last white pants—directed villagers to place rains had fallen. He was greeted by a group stones in a 75-yard (68- meter) line between of about 50 people waiting in a dirt square two hills. "This is an ideal site," he under a banyan tree. The men wore loose- announced. His organization, Tarun Bharat fitting cotton pantaloons and turbans of Sangh, would provide the engineering orange, maroon, and white. -

Class Notes Class: Xii Subject: Geography Date

CLASS NOTES CLASS: XII SUBJECT: GEOGRAPHY DATE TOPIC: CH.4 HUMAN SETTLEMEN 1. Discuss the social and functional difference between urban and rural centers. Rural areas Urban areas Much smaller in areas with lesser population. Much larger in areas with higher density of population Majority of the population are engaged in secondary and People are directly related with land and more tertiary activities. than 75% of population engaged in primary activity. Urban areas draw the raw materials from rural areas for Rural areas depend on urban areas for processing in industries. marketing their goods and availing necessary So, it functions as a nodal point. services. In urban areas people share a formal relation and could not It is a hinter land of urban areas. develop intimacy as a result of constant movement. In rural areas there is less social mobility. People share a close social bonding. 2. What factors and conditions influence the rural settlement? Discuss the types of rural found in India. There are various factors and conditions responsible for having different types of rural settlements in India. These include: i) physical features (ii) cultural and ethnic iii) security factors factors nature of terrain, altitude, social structure, caste and defence against thefts and climate and religion robberies availability of water Rural settlements in India can broadly be put into four types: Nucleated Fragmented The clustered rural settlement is a compact or Semi-clustered or fragmented settlements closely built up area of houses. result from clustering in a restricted area of dispersed In this type of village, the general living area is settlement. -

29 Human Settlement

Human Settlement MODULE - 9 Human resource development in India 29 HUMAN SETTLEMENT Notes In the previous lesson, we have discussed about population composition; total population; rural-urban population; population growth, etc. In this lesson, our focus will be on human settlements. Therefore, discussion will revolve around the concept of settlements meaning and nature, evolution and classification of rural and urban settlements in India. OBJECTIVES After reading this lesson, you will be able to: describe the meaning of settlement; identify various types of rural settlements; describe various house types in India; establish the relationship between house types with relief, climate and building materials; define an urban areas as given by census of India; analyse the distributional patterns of rural and urban settlements; and explain functional classification of urban settlements as given by census of India. 29.1 WHAT IS A SETTLEMENT Though we use this term very frequently, but when it comes for defining, it is very difficult to give a clear cut definition. In simpler term we can define settlement as any form of human habitation which ranges from a single dowelling to large city. The word settlement has another connotation as well as this is a process of opening up and settling of a previously uninhabited area by the people. In geography this process is also known as occupancy. Therefore, we can say settlement is a process GEOGRAPHY 301 MODULE - 9 Human Settlement Human resource development in India of grouping of people and acquiring of some territory to build houses as well as for their economic support. Settlements can broadly be divided into two types – rural and urban. -

International Journal of Ayurveda and Pharma Research

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Journal of Ayurveda and Pharma Research Int. J. Ayur. Pharma Research, 2014; 2(1): 40-45 ISSN : 2322 - 0910 International Journal of Ayurveda and Pharma Research Research Article ETHNO-VETERINARY HERBAL REMEDIES OF GUJJARS AND OTHER FOLKLORE COMMUNITIES OF ALWAR DISTRICT, RAJASTHAN, INDIA M. L. Sanyasi Rao1*, N. Ramakrishna2, Ch. Saidulu3 *1Ethno botanist at Anthra NGO, Secunderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India. 2Lecturer in Botany, Department of Botany SAP College, Vikarabad, R.R. District, Andhra Pradesh, India. 3Research scholar, Department of Botany, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India. Received on: 28/01/2014 Revised on: 10/02/2014 Accepted on: 20/02/2014 ABSTRACT The present study encompasses the in-depth investigation on Medicinal plants which were used on Ethno-veterinary medicine in the district of Alwar, Rajasthan India. The present ethno-botanical explorations conducted in the Alwar district of Rajasthan revealed that about 37 species of plants belonging to 32 genera under 24 families have been noticed which they use for veterinary health care. A total of 27 healers and herbal practitioners were interviewed during the study. Total of 47 remedies were recorded for 19 veterinary disease conditions of which 21 remedies were recorded under digestive disorders (9 remedies for bloat, 3 stomach pain and 5 for constipation, 3 food poison and 1 diarrhoea) 9 remedies under reproductive problems (3 for anoestrus, 2 for galactagogue, 3 for retained placenta, and 1 for prolapsed uterus). 5 remedies for diseases of sense organs (2 skin infection, 3 for wounds and maggot wounds). -

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Manager Mobile No

Mapped FLC Details Mapped Bank Branch Details ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Manager Mobile No. Of FLC Manager Landline of FLC Address Name of Bank Name of Branch Name of Branch Manager Mobile No. of Manager Landline No. Address PR08000005 T.P Pareek I.T.C Vidyanagar Ganeshpura Road Beawar P 9-Vidyanagar Ganeshpura Beawar Rajasthan Ajmer NULL Ajmer Bank Of Baroda A K Bos ( Since Resign) 9414007977 BOB Rly Camp St Road Ajmer HDFC HDFC,Beawar HARSH BAMBA 9828049697 01462-512010 Beawar PR08000121 Raghukul Industrial Training Center P Balupura road, Adarsh nagar Rajasthan Ajmer NULL Ajmer Bank Of Baroda A K Bos ( Since Resign) 9414007977 BOB Rly Camp St Road Ajmer Bank of Baroda BOB Adhersh Nager Rakesh Bhargva 8094015498 0145 3299898 Adresh nager Ajmer PR08000438 Raj Industrial Training Centre Sirfvikisan Chatavas P Sirvisan Chatravas Ganeshpura Road Beawar Rajasthan Ajmer NULL Ajmer Bank Of Baroda A K Bos ( Since Resign) 9414007977 BOB Rly Camp St Road Ajmer HDFC HDFC,Beawar HARSH BAMBA 9828049697 01462-512010 Beawar PR08000454 Shri Baba Ramdev Pvt. Industrial Training Institute, P Arjunpura (Jagir), Via Mangliwas Rajasthan Ajmer NULL Ajmer BRKGB S K Mittal 9461016730 BRKGB,Adresh Nager Ajmer UBI UBI Manlgliyawas Sh.Gulab Singh 9783301076 0145-2785226 Mangliyawas PR08000471 Shri Balaji ITC P V & P Bandanwara, P.S Bhinay Rajasthan Ajmer NULL Ajmer BRKGB S K Mittal 9461016730 BRKGB,Adresh Nager Ajmer BRKGB BRKGB,Bandenwara Mr S K Jain 7726854671 01466-272020 Bandenwara -

The Gujarati Lyrics of Kavi Dayarambhal

The Gujarati Lyrics of Kavi Dayarambhal Rachel Madeline Jackson Dwyer School of Oriental and African Studies Thesis presented to the University of London for the degree PhD July 1995 /f h. \ ProQuest Number: 10673087 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673087 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Kavi Dayarambhal or Dayaram (1777-1852), considered to be one of the three greatest poets of Gujarati, brought to an end not only the age of the great bhakta- poets, but also the age of Gujarati medieval literature. After Dayaram, a new age of Gujarati literature and language began, influenced by Western education and thinking. The three chapters of Part I of the thesis look at the ways of approaching North Indian devotional literature which have informed all subsequent readings of Dayaram in the hundred and fifty years since his death. Chapter 1 is concerned with the treatment by Indologists of the Krsnaite literature in Braj Bhasa, which forms a significant part of Dayaram's literary antecedents. -

The Commodification of Rajasthani Folk Performance at Chokhi Dhani

Preserving the Fine Village: Commodification In Imagined Spaces Preserving the “Fine Village”: The Commodification of Rajasthani Folk Performance at Chokhi Dhani Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in Theatre in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University By Leela Singh The Ohio State University April 2014 Project Advisor: Jennifer Schlueter, Department of Theatre 1 Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………3-4 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………..5 I. Welcome to Delhi…………………………………………………………….......6 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………...7-12 II. The Pink City……………………………………………………………………13 Section 1: Touring Chokhi Dhani………………………………………………………….14-20 III. Delhi Belly……………………………………………………………………..21 Section 2: The Dancers and Musicians…………………………………………………….22-30 Section 3: The Storytellers………………………………………………………………....31-38 IV. Monsoon Season……………………………………………………………….39 Section 4: The Present and Future Performer……………………………………………...40-43 V. The Pink City One More Time …………………………………………………44-45 The Subaltern Voice of the Folk Performer (Limitations) ………………………………...46-48 Recommendations …………………………………………………………………………49 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………..50-52 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………53-54 Footnotes…………………………………………………………………………….54-57 2 Acknowledgements This thesis would not be possible without the help of an enormous number of dedicated, kind individuals. I owe many thanks. I would first like to thank The Ohio State University Holbrook Research Abroad Fellowship for funding this research, as well as the Undergraduate Research Office—especially Helene Cweren and Jackie Lipphardt—for their guidance and support in the months leading up to my departure and during my time overseas. I would be disastrously remiss if I did not thank my tireless and fearless advisor, Jennifer Schlueter, who jumped right in on my thesis and has served throughout my time at OSU as the best mentor I could ever have hoped for. -

Arvari Basin Substate BSAP

ARVARI CATCHMENT A SUB-STATE SITE IN RAJASTHAN BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN Coordinated by Dr. Om Prakash Kulhari TARUN BHARAT SANGH Bheekampura – Kishori, Thanagazi, Alwar – 301022 (Rajasthan) Table of Contents Page No. (i) Preface and Acknowledgements I (ii) Abbreviations and acronyms II (iii) Glossary of local terms III (iv) Executive Summary IV (v) Map of Arvari catchment XVI Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.1. Background 1 1.2. Scope 4 1.3. Objectives 5 1.4. Contents 6 1.5. Methodology 7 1.5.1. Field Study 8 1.5.2. Public Participation 10 1.5.3. Consultation of Secondary Sources 11 Chapter 2: Profile of Arvari Catchment 12 2.1. Geographical Profile 12 2.2. Socio-economic Profile 14 2.3. Political Profile 15 2.4. Ecological Profile 15 2.4.1. Forest Eco-system 15 2.4.2. Agriculture System 18 2.4.3. Water Bodies 18 2.5. Brief History 20 Chapter 3: Current (Known) Range and Status of Biodiversity 25 3.1. State of Natural Eco-systems and Biodiversity 25 3.2. State of Agricultural Eco-systems and Domesticated Plant / Animal Species 29 3.2.1. Improved Crop Varieties 30 3.2.2. Vegetables and Fruits 31 3.2.3. Domesticated Animals 35 Chapter 4: Statement of Problems Related to Biodiversity 38 4.1. Domesticated Biodiversity 38 2 4.1.1. Loss of Traditional Crops 38 4.1.2. Domesticated Animals 39 4.2. Wild Biodiversity 40 4.2.1. Forests 40 4.2.2. Wild Animals 42 4.2.3. Mining 43 Chapter 5: Major Actors and Their Current Roles Relevant to Biodiversity 45 5.1.