Copyright © Michael Uhall 1 Not to Be Cited, Copied, Or Shared Without Permission. the World for Word Is Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorable Quotations I Have Found William James – the Greatest

Memorable Quotations I Have Found William James – The greatest discovery of my generation is that a human being can alter his life by altering his attitude. Mother Theresa – We cannot do great things on this earth. We can only do small things with great love. Mark Twain – I have been through some terrible things in my life, some of which actually happened. Blaise Pascal – All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone. Ben Franklin – Our limited perspective, our hopes and fears become our measure of life, and when circumstances don’t fit our ideas, they become our difficulties. Lyndon Baines Johnson – You ain’t learnin’ nothin’ when you’re talkin’! Booker T. Washington – Few things help an individual more than to place responsibility upon him, and to let him know you trust him. Saint Augustine – Hope has two beautiful cousins: anger and courage; anger at the way things are and the courage to change them. Hubert H. Humphrey – We welcome a world of diversity, a world all richer for the many different and distinctive strands of which it is woven. Eleanor Roosevelt – A mature person is one who does not think only in absolutes, who is able to be objective even when deeply stirred emotionally, who has learned that there is both good and bad in all people and in all things and who walks humbly and deals charitably with the circumstances of life knowing that in this world no one is all knowing and therefore all of us need both love and charity. -

Dante's Inferno

Dante’s Inferno: Critical Reception and Influence David Lummus Dante and the Divine Comedy have had a profound influence on the production of literature and the practice of literary criticism across the Western world since the moment the Comedy was first read. Al- though critics and commentators normally address the work as a whole, the first canticle, Inferno, is the part that has met with the most fervent critical response. The modern epoch has found in it both a mirror with which it might examine the many vices and perversions that define it and an obscure tapestry of almost fundamentalist pun- ishments that are entirely alien to it. From Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and Osip Mandelstam in the early twentieth century to Seamus Heaney, W. S. Merwin, and Robert Pinsky at century’s end, modern poets of every bent have been drawn to the Inferno and to the other two canti- cles of the Comedy as an example of poetry’s world-creating power and of a single poet’s transcendence of his own spiritual, existential, and political exile.1 To them Dante was and is an example of how a poet can engage with the world and reform it, not just represent it, through the power of the poetic imagination. In order to understand how Dante and his poem have been received by critics and poets in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, we must glance—however curso- rily—at the seven-hundred-year critical tradition that has formed the hallowed academic institution of Dante studies. In this way, we can come to see the networks of understanding that bind Dante criticism across its history. -

Around the Globe Stanford Humanities Center Stanford Humanities Center Annual Report 2008–09

STANFORD HUMANITIES CENTER Annual Report 2008-09 STANFORD HUMANITIES CENTER 424 Santa Teresa Street Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-4015 T 650.723.3052 HUMANITIES F 650.723.1895 http://shc.stanford.edu AROUND THE GLOBE STANFORD HUMANITIES CENTER Stanford Humanities Center Annual Report 2008–09 Founded in 1980, the Stanford Humanities Center is a multidisciplinary research institute at Stanford dedicated to advancing knowledge about culture, philosophy, history, and the arts. The Center’s fellowships, research workshops, and public events strengthen the intellectual and creative life of the university, foster innovative scholarship and teaching, and enrich our understanding of the human experience. 6 10 Geballe Research Workshops Events For more information on the The Center’s research work- The Humanities Center invites Stanford Humanities Center, shops bring together faculty and experts from around the world visit our new website at: graduate students to explore to Stanford to share the results http://shc.stanford.edu new areas of inquiry, sparking of their research into human “The Humanities Center is a sanctuary at the heart of the university. It has innovation in a broad spectrum values, creativity, and experience. the intellectual vigor and collegiality that make Stanford exceptional, while of established and emerging Recordings are available providing relief from administrative cares and making it possible for the disciplines. at http://shc.stanford.edu/ fellows to focus on research and writing.” intellectual-life/video- David Holloway, Donald Andrews Whittier Fellow, 2005–06 podcasts. 2 PHOTOS COVER AND THIS PAGE : Steve Castillo PHOTOS : TOP LEFT : Nicole Coleman. TOP CENTER AND RIGHT : Steve Castillo. BOTTOM : Helga Sigvaldadóttir. -

![Duncan, Ifor. 2021. Hydrology of the Powerless. Doctoral Thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5057/duncan-ifor-2021-hydrology-of-the-powerless-doctoral-thesis-goldsmiths-university-of-london-thesis-4405057.webp)

Duncan, Ifor. 2021. Hydrology of the Powerless. Doctoral Thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis]

Duncan, Ifor. 2021. Hydrology of the Powerless. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/29967/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] HYDROLOGY OF THE POWERLESS Ifor Duncan Submitted To Goldsmiths, University Of London As Required For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy Centre for Research Architecture Department of Visual Cultures Date: 30 September 2019 1 Declaration of Authorship I ____Ifor Duncan_______ hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented is largely my own but also contains research co-produced with colleague Stefanos Levidis, PhD Candidate (CRA). This is restricted to Part I: Fluvial Frontier. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ________ ______________ Date: 30/09/2019 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisors Susan Schuppli and Ayesha Hameed for their continued support and insight, and for the inspiration I take from their research and profound practices. I would also like to thank Astrid Schmetterling, with whom I started this process, for her generosity and kindness. I would also like to thank the staff of Visual Cultures and CRA for all of their help and guidance over the years, as well my upgrade examiners Shela Sheikh and Richard Crownshaw. -

Topographies of Memory and Amnesia in Poland and Spain

“WHERE FOOT KNOCKS AGAINST/THE UNBURIED BONES OF KIN”: TOPOGRAPHIES OF MEMORY AND AMNESIA IN POLAND AND SPAIN BY ALEXANDRA BROOKE VAN DOREN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2019 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Brett Kaplan, Chair Associate Professor Eric Calderwood Professor Elena Delgado Associate Professor George Gasyna ABSTRACT This dissertation identifies and refashions a critical point of convergence between Poland and Spain’s national histories under the umbrella of Holocaust and Memory Studies in its examination of selections from each country’s respective canon of film and literature pertaining to the Holocaust and Spanish Civil War. The resistance to literary and visual depictions of wartime memory in Poland and Spain poses a multitude of imperative questions that revolve around the denial of national guilt and the resulting government-sanctioned cultural amnesia. Two such illustrations of institutionalized practices of forgetting are Spain’s pacto de silencio (pact of silence), imposed after the death of Franco, and Poland’s recent law making it a criminal offense to discuss or imply Polish guilt in crimes of the Holocaust, which emerged as a product of a longstanding history of resisting any admission of collaboration or complicity. I will focus primarily on the intersections between the survivor testimony and stories of witness that began to surface both during and in the immediate wake of World War II in Poland and the Spanish Civil War in Spain and more recent depictions of the “black-listed” memory of the Holocaust and crimes of fascist dictatorships in twentieth and twenty first-century literature and film in both countries. -

TEST 2 Sepp's Program

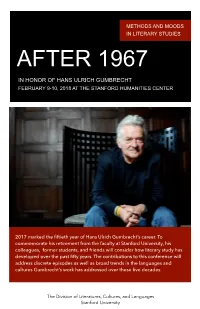

METHODS AND MOODS IN LITERARY STUDIES AFTER 1967 IN HONOR OF HANS ULRICH GUMBRECHT FEBRUARY 9-10, 2018 AT THE STANFORD HUMANITIES CENTER 2017 marked the fiftieth year of Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s career. To commemorate his retirement from the faculty at Stanford University, his colleagues, former students, and friends will consider how literary study has developed over the past fifty years. The contributions to this conference will address discrete episodes as well as broad trends in the languages and cultures Gumbrecht’s work has addressed over these five decades. The Division of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages Stanford University PROGRAM FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 9 8:30 a.m. Opening Remarks Richard Saller, Vernon R. and Lysbeth Warren Anderson Dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences, Stanford University Dan Edelstein, Chair of the Division of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages, Stanford University David Shaw, Bradford M. Freeman Director of Football, Stanford University 9:00 a.m. Keynote Lecture Chair: John Bender, Stanford University Karen Feldman, University of California, Berkeley "Afterlives of Structure: Begriffsgeschichte, Deconstruction, Reception" 10:15 a.m. Break 10:30 a.m. Literary Studies in 1967—and After Chair: Niklaus Largier, University of California, Berkeley William Egginton, The Johns Hopkins University "The Recuperation of Presence" Marci Shore, Yale University "What Is Heroic Thinking?" Rüdiger Campe, Yale University "Questions of Evidence: Gumbrecht's Contribution to Dramatic Theory" Horst Bredekamp, Humboldt University -

The Tapestry of Memory

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-28-2017 12:00 AM The Tapestry of Memory Kathryn M. Lawson The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Antonio Calcagno The University of Western Ontario Dr. Helen Fielding The University of Western Ontario Dr. Jan Plug The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kathryn M. Lawson 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Continental Philosophy Commons, Fine Arts Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, Illustration Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Painting Commons, and the Photography Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Kathryn M., "The Tapestry of Memory" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4866. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4866 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lawson ii Abstract Rationality points to the complete annihilation and end of a life when the body perishes, and yet when a loved one dies we continue to experience that person in a myriad of ways. The focus of this thesis will be a phenomenological exploration of the earthly afterlife of those we have loved and lost. By positing the subject as always inter-subjective and as temporal in nature, this thesis will investigate how we continue to create and interact with the deceased upon the earth. -

Full Dissertation

The Rise of Insider Iconography: Visions of Soviet Turkmenia in Russian-Language Literature and Film, 1921–1935 Katharine M. Holt To be submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Katharine M. Holt All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Rise of Insider Iconography: Visions of Soviet Turkmenia in Russian-Language Literature and Film, 1921–1935 Katharine M. Holt This study investigates how Turkestan generally and Turkmenia more specifically were represented in Russian-language film and literature in the early Soviet period. By analyzing the work of writers and filmmakers as well as the ideological and artistic constraints that they faced, I explore not only depictions of these spaces, but also the biographies of several of their key depicters, delving into the historical circumstances in which given texts were produced and the relationship between these texts and the larger artistic fields into which they were released. The study opens with a discussion of texts by “outsiders” who positioned Turkmenia as a space worthy of exploration between 1921 and 1927. Chapter One examines two essay collections by the Eurasianists—Iskhod k vostoku. Predchuvstviia i sversheniia. Utverzhdenie evraziitsev (Exit to the East: Forebodings and Events: An Affirmation of the Eurasians, 1921) and Na putiakh. Utverzhdenie evraziitsev (On the Way: An Affirmation of the Eurasians, 1922)— as well as Dziga Vertov’s documentary film Shestaia chast’ mira (One Sixth of the World, 1926) and two literary works by Nikolai Tikhonov, a “fellow traveler” who passed through Turkmenistan in the mid-1920s. -

Entitled Opinions (About Life and Literature) with Robert Harrison SC1089

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8v19s4b0 Online items available Guide to the Entitled Opinions (About Life and Literature) with Robert Harrison SC1089 Daniel Hartwig Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2010 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Entitled Opinions SC1089 1 (About Life and Literature) with Robert Harrison SC1089 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Entitled opinions (about life and literature) with Robert Harrison creator: Harrison, Robert Pogue. Identifier/Call Number: SC1089 Physical Description: 6615.04 megabyte(s)(220 computer files) Date (inclusive): 2005-2017 Abstract: The materials consist of program audiorecordings of Robert Harrison's show "Entitled opions (about life and literature)" broadcast on KZSU 90.1 Wednesdays from 2-3PM. Information about Access This collection is open for research. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/pubserv/permissions.html. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. -

Fall 2014 Contents

Recently Published Fall 2014 Contents General Interest 1 Special Interest 30 Paperbacks 91 Land and Wine The Oldest Living The French Terroir Thing in the World Distributed Books 120 Charles Frankel Rachel Sussman ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01469-2 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-05750-7 Cloth $27.50/£19.50 Cloth $45.00/£31.50 Author Index 200 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01472-2 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-05764-4 Title Index 202 Subject Index 204 Ordering Inside Information back cover The Trilobite Book Snakes, Sunrises, A Visual Journey and Shakespeare Riccardo Levi-Setti How Evolution Shapes ISBN-13: 978-0-226-12441-4 Our Loves and Fears Cloth $45.00/£31.50 Gordon H. Orians E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-12455-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00323-8 Cloth $30.00/£21.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00337-5 D-Day through Scientific Style and French Eyes Format Normandy 1944 The CSE Manual for Authors, Cover photograph by Terry Whittaker from Mary Louise Roberts Editors, and Publishers The Wild Cat Book by Fiona and Mel Sunquist. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-13699-8 Council of Science Editors Cloth $55.00/£17.50 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-11649-5 Cover design by Alice Reimann E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-13704-9 Cloth $70.00/£49.00 Catalog design by Alice Reimann and Mary Shanahan ROT BER POGUE HARRISON Juvenescence A Cultural History of Our Age ow old are you? The more thought you bring to bear on the question, the harder it is to answer.