Anemia in the Emergency Department: Evaluation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phenotypic and Molecular Genetic Analysis of Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency in a Tunisian Family

The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics (2016) 17, 265–270 HOSTED BY Ain Shams University The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics www.ejmhg.eg.net www.sciencedirect.com ORIGINAL ARTICLE Phenotypic and molecular genetic analysis of Pyruvate Kinase deficiency in a Tunisian family Jaouani Mouna a,1,*, Hamdi Nadia a,1, Chaouch Leila a, Kalai Miniar a, Mellouli Fethi b, Darragi Imen a, Boudriga Imen a, Chaouachi Dorra a, Bejaoui Mohamed b, Abbes Salem a a Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Hematology, Pasteur Institute, Tunis, Tunisia b Service d’Immuno-He´matologie Pe´diatrique, Centre National de Greffe de Moelle Osseuse, Tunis, Tunisia Received 9 July 2015; accepted 6 September 2015 Available online 26 September 2015 KEYWORDS Abstract Pyruvate Kinase (PK) deficiency is the most frequent red cell enzymatic defect responsi- Pyruvate Kinase deficiency; ble for hereditary non-spherocytic hemolytic anemia. The disease has been studied in several ethnic Phenotypic and molecular groups. However, it is yet an unknown pathology in Tunisia. We report here, the phenotypic and investigation; molecular investigation of PK deficiency in a Tunisian family. Hemolytic anemia; This study was carried out on two Tunisian brothers and members of their family. Hematolog- Hydrops fetalis; ical, biochemical analysis and erythrocyte PK activity were performed. The molecular characteriza- PKLR mutation tion was carried out by gene sequencing technique. The first patient died few hours after birth by hydrops fetalis, the second one presented with neonatal jaundice and severe anemia necessitating urgent blood transfusion. This severe clinical pic- ture is the result of a homozygous mutation of PKLR gene at exon 8 (c.1079G>A; p.Cys360Tyr). -

Non-Commercial Use Only

only use Non-commercial 14th International Conference on Thalassaemia and Other Haemoglobinopathies 16th TIF Conference for Patients and Parents 17-19 November 2017 • Grand Hotel Palace, Thessaloniki, Greece only use For thalassemia patients with chronic transfusional iron overload... Make a lasting impression with EXJADENon-commercial film-coated tablets The efficacy of deferasirox in a convenient once-daily film-coated tablet Please see your local Novartis representative for Full Product Information Reference: EXJADE® film-coated tablets [EU Summary of Product Characteristics]. Novartis; August 2017. Important note: Before prescribing, consult full prescribing information. iron after having achieved a satisfactory body iron level and therefore retreatment cannot be recommended. ♦ Maximum daily dose is 14 mg/kg body weight. ♦ In pediatric patients the Presentation: Dispersible tablets containing 125 mg, 250 mg or 500 mg of deferasirox. dosing should not exceed 7 mg/kg; closer monitoring of LIC and serum ferritin is essential Film-coated tablets containing 90 mg, 180 mg or 360 mg of deferasirox. to avoid overchelation; in addition to monthly serum ferritin assessments, LIC should be Indications: For the treatment of chronic iron overload due to frequent blood transfusions monitored every 3 months when serum ferritin is ≤800 micrograms/l. (≥7 ml/kg/month of packed red blood cells) in patients with beta-thalassemia major aged Dosage: Special population ♦ In moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh B) dose should 6 years and older. ♦ Also indicated for the treatment of chronic iron overload due to blood not exceed 50% of the normal dose. Should not be used in severe hepatic impairment transfusions when deferoxamine therapy is contraindicated or inadequate in the following (Child-Pugh C). -

Section 8: Hematology CHAPTER 47: ANEMIA

Section 8: Hematology CHAPTER 47: ANEMIA Q.1. A 56-year-old man presents with symptoms of severe dyspnea on exertion and fatigue. His laboratory values are as follows: Hemoglobin 6.0 g/dL (normal: 12–15 g/dL) Hematocrit 18% (normal: 36%–46%) RBC count 2 million/L (normal: 4–5.2 million/L) Reticulocyte count 3% (normal: 0.5%–1.5%) Which of the following caused this man’s anemia? A. Decreased red cell production B. Increased red cell destruction C. Acute blood loss (hemorrhage) D. There is insufficient information to make a determination Answer: A. This man presents with anemia and an elevated reticulocyte count which seems to suggest a hemolytic process. His reticulocyte count, however, has not been corrected for the degree of anemia he displays. This can be done by calculating his corrected reticulocyte count ([3% × (18%/45%)] = 1.2%), which is less than 2 and thus suggestive of a hypoproliferative process (decreased red cell production). Q.2. A 25-year-old man with pancytopenia undergoes bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, which reveals profound hypocellularity and virtual absence of hematopoietic cells. Cytogenetic analysis of the bone marrow does not reveal any abnormalities. Despite red blood cell and platelet transfusions, his pancytopenia worsens. Histocompatibility testing of his only sister fails to reveal a match. What would be the most appropriate course of therapy? A. Antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine, and prednisone B. Prednisone alone C. Supportive therapy with chronic blood and platelet transfusions only D. Methotrexate and prednisone E. Bone marrow transplant Answer: A. Although supportive care with transfusions is necessary for treating this patient with aplastic anemia, most cases are not self-limited. -

Tareq Al-Adaily Ibrahim Elhaj Ayah Fraihat Dana Alnasra Sheet

Anemia of decreased production II Sheet 3 – + Hemolytic anemia Dana Alnasra Ayah Fraihat Ibrahim Elhaj Tareq Al-adaily 0 **Flashback to previous lectures: − Anemia is the reduction of oxygen carrying capacity of blood secondary to a decrease in red cell mass. − We classified anemia according to cause into: 1. Anemia of blood loss (chronic and acute) 2. Anemia of decreased production 3. Hemolytic anemia − Then, we mentioned general causes for the anemia of decreased production, which are: nutritional deficiency, chronic inflammation, and bone marrow failure. We’ve already discussed the first two and now we will proceed to the last one. Anemias resulting from bone marrow failure: 1. Aplastic anemia 2. Pure red cell aplasia 3. Myelophthisic anemia 4. Myelodysplastic syndrome Other anemias of decreased production: 1. Anemia of renal failure 2. Anemia of liver disease 3. Anemia of hypothyroidism 00:00 1. Aplastic anemia Is a condition where the multipotent myeloid stem cells produced by the bone marrow are damaged. Remember: the bone marrow has stem cells called myeloid stem cells which eventually differentiate into erythrocytes, megakaryocytes (platelets), and myeloblasts (white blood cells). Notice that lymphocytes are not produced from the myeloid progenitor, therefore, they are not affected. depleted normal 1 | P a g e As a result, the bone marrow becomes depleted of hematopoietic cells. And this is reflected as peripheral blood pancytopenia (all blood cells -including reticulocytes- are decreased, with the exception of lymphocytes). Pathogenesis There are two forms of aplastic anemia according to pathogenesis: a. Acquired aplastic anemia It happens because of an extrinsic factor e.g. -

Hb S/Beta-Thalassemia

rev bras hematol hemoter. 2 0 1 5;3 7(3):150–152 Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia Brazilian Journal of Hematology and Hemotherapy www.rbhh.org Scientific Comment ଝ The compound state: Hb S/beta-thalassemia ∗ Maria Stella Figueiredo Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil Sickle cell disease (SCD) results from a single amino acid small increase in Hb concentration and in packed cell volume. substitution in the gene encoding the -globin subunit However, these effects are not accompanied by any reduction  ( 6Glu > Val) that produces the abnormal hemoglobin (Hb) in vaso-occlusive events, probably due to the great number of named Hb S. SCD has different genotypes with substantial Hb S-containing red blood cells resulting in increased blood 1,2 4,5 variations in presentation and clinical course (Table 1). The viscosity. combination of the sickle cell mutation and beta-thalassemia A confusing diagnostic problem is the differentiation 0  (-Thal) mutation gives rise to a compound heterozygous con- of Hb S/ -Thal from sickle cell anemia associated with ␣ dition known as Hb S/ thalassemia (Hb S/-Thal), which was -thalassemia. Table 2 shows that hematologic and elec- 3 first described in 1944 by Silvestroni and Bianco. trophoretic studies are unable to distinguish between the two The polymerization of deoxygenated Hb S (sickling) is the conditions and so family studies and DNA analysis are needed 5 primary event in the molecular pathogenesis of SCD. How- to confirm the diagnosis. +  ever, this event is highly dependent on the intracellular Hb In Hb S/ -Thal, variable amounts of Hb A dilute Hb S and composition; in other words, it is dependent on the concen- consequently inhibit polymerization-induced cellular dam- tration of Hb S, and type and concentration of the other types age. -

Severe Aplastic Anemia

Severe AlAplas tic AiAnemia Monica S. Thakar, MD Pediatric BMT Medical College of Wisconsin Outline of Talk 1. Clinical description of aplastic anemia 2. Data collection forms And a couple of quizzes in between… CLINICAL DESCRIPTIONS What is aplastic anemia? • More than just anemia – Involves low counts in 2 of 3 cell lines: red blood cells (RBC), white blood cells (WBC), pltltlatelets • Should NOT involve dysplasia – EiException: RBC can sometimes be dlidysplastic • Should have NORMAL cytogenetics • If dysplasia (beyond RBCs) or abnormal cytogenetics seen, think myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) What is “severe” aplastic anemia? • Marrow cellularity ≤25% AND • Two of the following peripheral blood features: – Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) < 0.5 x 109/L – Platelet count <20 x 109/L – Absolute reticulocyte count < 40 x 109/L • “Very” severe aplastic anemia – Same as above except ANC <0.2 x 109/L NORMAL BttBottom Li ne: Severely Reduced HtitiHematopoietic Stem Cell Precursors SEVERE APLASTIC ANEMIA IBIn Bone M arrow Epidemiology • Half of cases seen in first 3 decades of life • Incidence: – 2 cases/m illion in WtWestern countitries – 2‐3 fold higher in Asia • Ethnic predisposition: – Asian • Genetics vs different environmental exposures? • Sex predisposition: M:F is 1:1 Pathoppyhysiology : 3 Main Mechanisms Proposed 1. Immune‐mediated – HthiHypothesis: RdRevved‐up T cells dtdestroy stem cells – Observation: Immunosuppression improves blood counts 2. Stem‐cell “depletion” or “defect” – Hypothesis: Drugs or viruses directly destroy stem cells -

ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine Nitrate/Nitrite Toxicity

ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine Nitrate/Nitrite Toxicity Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Case Studies in Environmental Medicine (CSEM) Nitrate/Nitrite Toxicity Course: WB2342 CE Original Date: December 5, 2013 CE Expiration Date: December 5, 2015 Key • Nitrate toxicity is a preventable cause of Concepts methemoglobinemia. • Infants younger than 4 months of age are at particular risk of nitrate toxicity from contaminated well water. • The widespread use of nitrate fertilizers increases the risk of well-water contamination in rural areas. About This This educational case study document is one in a series of and Other self-instructional modules designed to increase the primary Case Studies care provider’s knowledge of hazardous substances in the in environment and to promote the adoption of medical Environmen- practices that aid in the evaluation and care of potentially tal Medicine exposed patients. The complete series of Case Studies in Environmental Medicine is located on the ATSDR Web site at URL: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.html In addition, the downloadable PDF version of this educational series and other environmental medicine materials provides content in an electronic, printable format. Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the work of the medical writers, editors, and reviewers in producing this educational resource. Contributors to this version of the Case Study in Environmental Medicine are listed below. Please Note: Each content expert for this case study has indicated that there is no conflict of interest that would bias the case study content. CDC/ATSDR Author(s): Kim Gehle MD, MPH CDC/ATSDR Planners: Charlton Coles, Ph.D.; Kimberly Gehle, MD; Sharon L. -

Newborn Screening Result for Bart's Hemoglobin

NEWBORN SCREENING RESULT FOR BART’S HEMOGLOBIN Physician’s information sheet developed by the Nebraska Newborn Screening Program with review by James Harper, MD, Pediatric Hematologist with UNMC Follow-up program, and member of the Nebraska Newborn Screening Advisory Committee. BACKGROUND The alpha thalassemias result from the loss of alpha globin genes. There are normally four genes for alpha globin production so that the loss of one to four genes is possible. The lack of one gene causes alpha thalassemia 2 (silent carrier) with no clinically detectable problems but may cause small amounts of hemoglobin Barts to be present in newborn blood samples. Alpha thalassemia trait (Alpha thalassemia 1) results from loss of two genes and causes a mild microcytic anemia which may resemble iron deficiency anemia. The loss of three genes causes hemoglobin H diseases which is a moderately severe form of thalassemia. The lack of all four genes causes hydrops fetalis and is usually fatal in utero. In general, only the loss of one or two genes is seen in African Americans. Individuals from Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean may have all four types of alpha thalassemia. The percentage of hemoglobin Barts in the blood sample may indicate the number of alpha genes that have been lost. However, the percentage of hemoglobin Barts is not directly measurable with the current methodology used by the newborn screening laboratory. Only the presence of Barts hemoglobin in relation to fetal and adult hemoglobin, and variants S, C, D and E can be detected. RECOMMENDED WORK UP In addition to the standard newborn hemoglobinopathy confirmation (hemoglobin electrophoresis), to separate those patients with alpha thalassemia silent carrier from the patients with alpha thalassemia trait, we recommend that these babies have the following labs drawn at their 6 month well baby check: CBC with retic count, ferritin, and a hemoglobin electropheresis. -

The Hematological Complications of Alcoholism

The Hematological Complications of Alcoholism HAROLD S. BALLARD, M.D. Alcohol has numerous adverse effects on the various types of blood cells and their functions. For example, heavy alcohol consumption can cause generalized suppression of blood cell production and the production of structurally abnormal blood cell precursors that cannot mature into functional cells. Alcoholics frequently have defective red blood cells that are destroyed prematurely, possibly resulting in anemia. Alcohol also interferes with the production and function of white blood cells, especially those that defend the body against invading bacteria. Consequently, alcoholics frequently suffer from bacterial infections. Finally, alcohol adversely affects the platelets and other components of the blood-clotting system. Heavy alcohol consumption thus may increase the drinker’s risk of suffering a stroke. KEY WORDS: adverse drug effect; AODE (alcohol and other drug effects); blood function; cell growth and differentiation; erythrocytes; leukocytes; platelets; plasma proteins; bone marrow; anemia; blood coagulation; thrombocytopenia; fibrinolysis; macrophage; monocyte; stroke; bacterial disease; literature review eople who abuse alcohol1 are at both direct and indirect. The direct in the number and function of WBC’s risk for numerous alcohol-related consequences of excessive alcohol increases the drinker’s risk of serious Pmedical complications, includ- consumption include toxic effects on infection, and impaired platelet produc- ing those affecting the blood (i.e., the the bone marrow; the blood cell pre- tion and function interfere with blood cursors; and the mature red blood blood cells as well as proteins present clotting, leading to symptoms ranging in the blood plasma) and the bone cells (RBC’s), white blood cells from a simple nosebleed to bleeding in marrow, where the blood cells are (WBC’s), and platelets. -

December Is National Aplastic Anemia Awareness Month

December Is National Aplastic Anemia Awareness Month What Is Aplastic Anemia? Aplastic anemia is a non-cancerous disease that occurs when the bone marrow stops making enough blood cells. The body makes three types of blood cells: red blood cells, which contain hemoglobin and deliver oxygen to all parts of the body white blood cells, which help fight infection platelets, which help blood clot when you bleed These blood cells are made in the bone marrow, which is the soft, sponge-like material found inside bones. The bone marrow contains immature cells called stem cells that produce blood cells. Stem cells grow into red cells, white cells, and platelets or they can make more stem cells. In patients who have aplastic anemia, there are not enough stem cells in the bone marrow to make enough blood cells. Picture of blood cells maturing from stem cells. Experts believe that aplastic anemia is an autoimmune disorder. This means that the patient’s immune system (which helps fight infection) reacts against the bone marrow and the bone marrow is not able to make blood cells. Stem cells are no longer being replaced and the left over stem cells are not working well. Therefore, the amount of red cells, white cells, and platelets begin to drop. If blood levels drop too low, a person can feel very tired (from low red cells), have bleeding or bruising (from low platelets), and/or have many or severe infections (from low white cells). What Are the Key Statistics About Aplastic Anemia? Aplastic anemia can occur in anyone of any age, race, or gender. -

A Case of Hemolysis and Methemoglobinemia Following Amyl Nitrite Use in an Individual with G6PD Deficiency

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Journal of Acute Medicine 3 (2013) 23e25 www.e-jacme.com Case Report A case of hemolysis and methemoglobinemia following amyl nitrite use in an individual with G6PD deficiency Anselm Wong*, Zeff Koutsogiannis, Shaun Greene, Shona McIntyre Victorian Poisons Information Centre, Austin Hospital, Heidelberg 3084, Victoria, Australia Received 28 August 2012; accepted 26 December 2012 Available online 5 March 2013 Abstract A 34-year-old man presented feeling generally unwell with dark urine 3 days after inhaling amyl nitrite. His initial heart rate was 118/min, blood pressure 130/85 mmHg, O2 saturation 85% on 15 L/min oxygen, and Glasgow coma score 15. He was pale, with clear chest sounds on auscultation. His hemoglobin was 60 g/L, bilirubin 112 mM, and methemoglobin concentration 6.9% on an arterial blood gas. Amyl nitrite- induced hemolysis and methemoglobinemia were diagnosed. Methylene blue was not administered because of the relatively low methemo- globin concentration and the possibility of inducing further hemolysis. He was subsequently confirmed as having glucose-6-phosphate dehy- drogenase deficiency, which had originally been diagnosed in childhood. Amyl nitrite toxicity may include concurrent methemoglobinemia and hemolysis. Administration of methylene blue for clinically significant methemoglobinemia can induce further hemolysis. Copyright Ó 2013, Taiwan Society of Emergency Medicine. Published by Elsevier Taiwan LLC. All rights reserved. Keywords: Amyl nitrite; Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency; Hematology; Toxicology 1. Introduction dark urine for 3 days following his return from Vanuatu 4 weeks earlier. He had drunk 100 half-coconut shells of kava Amyl nitrite is one of a number of alkyl nitrites otherwise while there. -

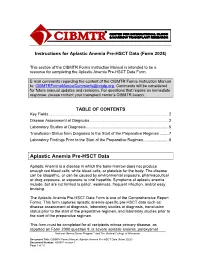

Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data (Form 2028)

Instructions for Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data (Form 2028) This section of the CIBMTR Forms Instruction Manual is intended to be a resource for completing the Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data Form. E-mail comments regarding the content of the CIBMTR Forms Instruction Manual to: [email protected]. Comments will be considered for future manual updates and revisions. For questions that require an immediate response, please contact your transplant center’s CIBMTR liaison. TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Fields ............................................................................................................. 2 Disease Assessment at Diagnosis ........................................................................ 2 Laboratory Studies at Diagnosis ........................................................................... 5 Transfusion Status from Diagnosis to the Start of the Preparative Regimen ........ 7 Laboratory Findings Prior to the Start of the Preparative Regimen ....................... 8 Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data Aplastic Anemia is a disease in which the bone marrow does not produce enough red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets for the body. The disease can be idiopathic, or can be caused by environmental exposure, pharmaceutical or drug exposure, or exposure to viral hepatitis. Symptoms of aplastic anemia include, but are not limited to pallor, weakness, frequent infection, and/or easy bruising. The Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data Form is one of the Comprehensive Report Forms. This form captures aplastic