Railways in WW2?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 " Sears Eldredge Macalester College

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Book Chapters Captive Audiences/Captive Performers 2014 Chapter 6a. "Chungkai Showcase": Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 " Sears Eldredge Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks Recommended Citation Eldredge, Sears, "Chapter 6a. "Chungkai Showcase": Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 "" (2014). Book Chapters. Book 16. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks/16 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Captive Audiences/Captive Performers at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 184 Chapter 6: “Chungkai Showcase” Chungkai Hospital Camp Part One: Mid-October 1942 to to Mid-May 1944 FIGURE 6.1. CHUNGKAI THEATRE LOGO. HUIB VAN LAAR. IMAGE COPYRIGHT MUSEON, THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS. Though POWs in other camps in Thailand produced amazing musical and theatrical offerings for their audiences, it was the performers in Chungkai who, arguably, produced the most diverse, elaborate, and astonishing entertainment on the Thailand-Burma railway. Between Christmas 1943 and May 1945 they presented over sixty-five musical or theatrical productions. As there is more detailed information about the administration, production, and reception of the entertainment at Chungkai than at any other camp on the railway, the focus in this chapter will be on those productions and personalities that stand out in some significant way artistically, technically, or politically. To cover this material adequately, the chapter will be divided into two parts: Part One will cover the period from mid-October 1942 to mid-May 1944; Part Two, from mid-May 1944 to July 1945. -

The Northern Corridor of the Trans-Asian Railway

ERINA REPORT Vol. 58 2004 JULY The Northern Corridor of the Trans-Asian Railway Pierre Chartier Economic Affairs Officer, UNESCAP Background formulation of rail and road networks with an emphasis on The 1980s and early 1990s witnessed some dramatic minimizing the number of routes to be included in the changes in the political and economic environment of networks and making maximum use of existing countries in the UNESCAP region. Peace returned to infrastructure; (iii) a focus on the facilitation of land Southeast Asia, countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia transport at border crossings through the promotion of became independent and a number of countries adopted relevant international conventions and agreements as an more market-oriented economic principles. These changes, important basis for the development of trade and tourism; which resulted in more outward-looking policies, led to and (iv) the promotion of close international cooperation unprecedented growth in trade to and from the UNESCAP with other United Nations agencies, including UNECE and region, at a rate that was twice the global figure. In UNCTAD2, as well as other governmental and non- addition, a salient feature of the region's trade growth was governmental organizations such as the International Union the increasing significance of trade within the region itself. of Railways (UIC), the Organization for Railway Concomitantly, the number of journeys by people within Cooperation (OSJD), the International Road Union (IRU) the region to neighboring countries for both tourism and and the International Road Federation (IRF). business purposes also soared. Each of these developments increased demands on the region's transport and The Trans-Asian Railway component of ALTID. -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

Members Newsletter

Castlemaine and Maldon Railway Preservation Members Society Newsletter January 2013 Fire Danger Reaches High Level - Diesel Power Now In Use Following a recent lineside fire near Muckleford, and with the current extended dry period, after a wet winter, the risk of fire from operating a steam locomotive has now risen to an unacceptable point and as such, we are now running all services with diesel-electric locomotive Y133, which is on long -term loan from our good friends at the Seymour Rail Heritage Centre. This will continue until the risk of fire has decreased to an acceptable level. Thank You Neville Many members will be saddened to know that at the last meeting of the Board of Management, the resignation of long time member and Responsible Officer, Neville Elliott, was accepted. Neville has worked tirelessly for the past 10 or 11 years in the position of responsible officer which involved a great deal of work around the time of the introduction of the Rail Safety Act and regulations, and he has done this work cheerfully and in a way that made the task of dealing with the new Act and regulations much more straightforward. Neville has decided that with some health issues becoming more evident that the time is right for him to step aside and he will now look towards involvement in other areas of the Railway, while assisting with the transition to a new Responsible Officer. The Board acknowledges Neville's contribution over the years and many will recall that he was awarded Honorary Life Membership of the Society at last year's Annual General Meeting. -

Safety Management Manual

SAFETY MANAGEMENT MANUAL Issue 6 Issue date: 15/5/2016 Implementation Date: 15/5/2016 Issued by the Responsible Officer on behalf of the Council, Geelong Steam Preservation Society (ACN 004 819 130), operator of The Bellarine Railway Controlled Document SAFETY MANAGEMENT MANUAL DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET Issued to: ________________________________ No:___________ Distribution of this document is controlled. It is issued to specific people and re-issues and revisions are controlled. Amendments can be recognised by revision numbers, and the date of issue printed on each page. Issue 6 Record of revisions: Revision Date Brief description No 1 1/10/03 P 18 Refers to standards of vegetation clearance P 23 New procedures for fatigue management Issue 4 1/10/05 Full re-issue Issue 5 1/11/2007 Full re-issue and re-format to take into account Schedule 2 of the Rail Safety Regulations (2006). 5/ Rev 01 9/4/2009 Minor changes reflecting establishment of Depot/workshops at Laker’s Siding. 5/ Rev 02 22/5/2010 6.2 Rail Safety Records 11 Management of Change 18 Competence training 26.3 Investigation format 5/ Rev 03 5/10/2013 6.2 Rail Safety Records 16.2 Revised risk matrix 26.3 Requirement to submit investigation reports to TSV Issue 6 15/5/2016 Full re-issue to format of Rail Safety National Law (Regulations Schedule 1 requirements) Persons receiving this document are responsible for: becoming and remaining familiar with its contents maintaining an up to date copy by following revision procedures following relevant procedures specified in the document -

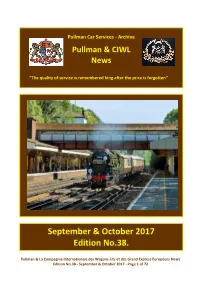

Pullman Car Services - Archive

Pullman Car Services - Archive Pullman & CIWL News “The quality of service is remembered long after the price is forgotten” September & October 2017 Edition No.38. Pullman & La Compagnie Internationale des Wagons -Lits et des Grand Express Européens News Edition No.38 - September & October 2017 - Page 1 of 72 COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Paul Blowfield - Communications & Marketing Officer, MNLPS - www.clan-line.org July 5th, 2017, marking 50 years to the day that the last steam hauled ‘Bournemouth Belle’ ran. The Merchant Navy Locomotive Preservation Society No.35028 Clan Line with ‘The Bournemouth Belle’ (Belmond British Pullman Cars) passing through Weybridge Station on the ‘Down’ main line. From the Coupé. Welcome aboard your bi-monthly newsletter. I take this opportunity to thank those readers who have kindly taken time to forward contributions in the form of articles and photographs for this edition. I remain dependent on contributions of news, articles (Word) and photographs (jpg) formats in all aspects of Pullman and CIWL operations both past, present, future and related aspects within model railways. All I ask of you for the time I spend in producing your newsletter, is for you to forward on by either E-mail or printing a copy, to any one you believe would be interested in reading your newsletter. Publication of the newsletter being scheduled on or about the 1st of January, March, May, July, September and November. The next edition editorial deadline date of Saturday October 28th, with the scheduled publication date of Wednesday November 1st, 2017. The views and articles within this publication are not necessarily those of the editor. -

The First Train Drivers from D to DR Light Rail 2019 North Tassie

April 2019 TM Remember when: The irst train drivers From D to DR Light Rail 2019 North Tassie trampings South East Queensland standard gauge The Great South Paciic Express goes west New loops, signalling & platform in the Central West Published monthly by the Australian Railway Historical Society (NSW Division) Editor Bruce Belbin April 2019 • $10.00 TM Assistant Editor Shane O’Neil April 2019 National Affairs Lawrance Ryan Volume 57, Number 4 Editorial Assistant Darren Tulk International Ken Date Remember when: General Manager Paul Scells The irst train drivers Subscriptions: Ph: 02 9699 4595 Fax: 02 9699 1714 Editorial Office: Ph: 02 8394 9016 Fax: 02 9699 1714 ARHS Bookshop: Ph: 02 9699 4595 Fax: 02 9699 1714 Mail: 67 Renwick Street, Redfern NSW 2016 Publisher: Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division, ACN 000 538 803 From D to DR Light Rail 2019 Print Post 100009942 North Tassie trampings South East Queensland standard gauge Publication No. The Great South Paciic Express goes west New loops, signalling & platform in the Central West Newsagent Ovato Retail Distribution Pty Ltd Published monthly by the Australian Railway Historical Society (NSW Division) Distribution Mailing & Distribution Ligare Pty Limited and Australia Post Printing Ligare Pty Limited Features Website www.railwaydigest.com.au Central West NSW: New loops, signalling and platform 30 Facebook www.facebook.com/railwaydigest In recent years a resurgence in intrastate freight business, especially Contributor Guidelines port-related container services and additional passenger services, has Articles and illustrations remain the copyright of the author and publisher. led to an increase in rail activity on the NSW Western Line. -

The Myth of the Standard Gauge

The Myth of the Standard Guage: Rail Guage Choice in Australia, 1850-1901 Author Mills, John Ayres Published 2007 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/426 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366364 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au THE MYTH OF THE STANDARD GAUGE: RAIL GAUGE CHOICE IN AUSTRALIA, 1850 – 1901 JOHN AYRES MILLS B.A.(Syd.), M.Prof.Econ. (U.Qld.) DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING, FINANCE & ECONOMICS GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2006 ii ABSTRACT This thesis describes the rail gauge decision-making processes of the Australian colonies in the period 1850 – 1901. Federation in 1901 delivered a national system of railways to Australia but not a national railway system. Thus the so-called “standard” gauge of 4ft. 8½in. had not become the standard in Australia at Federation in 1901, and has still not. It was found that previous studies did not examine cause and effect in the making of rail gauge choices. This study has done so, and found that rail gauge choice decisions in the period 1850 to 1901 were not merely one-off events. Rather, those choices were part of a search over fifty years by government representatives seeking colonial identity/autonomy and/or platforms for election/re-election. Consistent with this interpretation of the history of rail gauge choice in the Australian colonies, no case was found where rail gauge choice was a function of the disciplined search for the best value-for-money option. -

The Chinese Railway System

ASIA THE CHINESE RAILWAY SYSTEM By H. STRINGER CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THE WASON COLLECTION THIS BOOK IS THE GIFT OF Mrs. James McHugh Cornell University Library TF 101.S91 The Chinese railway system / 3 1924 023 644 143 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023644143 THE CHINESE RAILWAY SYSTEM THE CHINESE RAILWAY SYSTEM By H. STRINGER, b.a., cantab., a.m.lc.e. Resident Engineer, Peking-Mukden Railway. SHANGHAI KELLY AND WALSH, LIMITED. HONGKONG-SINGAPORE-YOKOHAMA-HANKOW. 1922. .. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. Railway History 1 II. Growth of the Railway Administration 27 III. The Government Railway System . 37 IV. Railways in Detail—Year 1918 . 74 V. The Economics of the Chinese Railways 107 VI. Pioneer Railway Location . 143 VII. The Case for Machinery on Railway Construction in China . 161 VIII. The Use of Reinforced Concrete on the Chinese Railways 177 IX. Construction Memoranda Peculiar to China 186 — ;; PREFACE This book is printed by order of the Board of Communications of the Chinese Government. I am greatly indebted to Mr. Tang Wen Kao, Director of the Peking-Mukden Railway and to Mr. L. J. Newmarch, Acting Engineer-in-Chief of the same line for making the necessary arrangements with the Board. The chapter on Pioneer Railway Location may perhaps be criticised as an irrelevancy. It is introduced to direct attention to a question of vast importance to a country which has practically all its railway future still before it, and also because location along pioneer lines is believed to be suited to existing financial conditions. -

Belt and Road Transport Corridors: Barriers and Investments

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Belt and Road Transport Corridors: Barriers and Investments Lobyrev, Vitaly and Tikhomirov, Andrey and Tsukarev, Taras and Vinokurov, Evgeny Eurasian Development Bank, Institute of Economy and Transport Development 10 May 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/86705/ MPRA Paper No. 86705, posted 18 May 2018 16:33 UTC BELT AND ROAD TRANSPORT CORRIDORS: BARRIERS AND INVESTMENTS Authors: Vitaly Lobyrev; Andrey Tikhomirov (Institute of Economy and Transport Development); Taras Tsukarev, PhD (Econ); Evgeny Vinokurov, PhD (Econ) (EDB Centre for Integration Studies). This report presents the results of an analysis of the impact that international freight traffic barriers have on logistics, transit potential, and development of transport corridors traversing EAEU member states. The authors of EDB Centre for Integration Studies Report No. 49 maintain that, if current railway freight rates and Chinese railway subsidies remain in place, by 2020 container traffic along the China-EAEU-EU axis may reach 250,000 FEU. At the same time, long-term freight traffic growth is restricted by a number of internal and external factors. The question is: What can be done to fully realise the existing trans-Eurasian transit potential? Removal of non-tariff and technical barriers is one of the key target areas. Restrictions discussed in this report include infrastructural (transport and logistical infrastructure), border/customs-related, and administrative/legal restrictions. The findings of a survey conducted among European consignors is a valuable source of information on these subjects. The authors present their recommendations regarding what can be done to remove the barriers that hamper international freight traffic along the China-EAEU-EU axis. -

By Train, Coach & Private Paddle Steamer

ictoria VBy Train, Coach & Private Paddle Steamer WITH SCOTT MCGREGOR 14 – 22 NOVEMBER 2020 • MELBOURNE • ECHUCA • BENDIGO • BALLARAT • HALLS GAP • • THE MURRAY RIVER • DAYLESFORD • MALDON • CASTEMAINE • MARYBOROUGH • • GEELONG AND THE BELLERAINE PENNINSULAR • THE GRAMPIAN’S NATIONAL PARK • INTRODUCTION The dawn of the railway age in Victoria was perfectly HIGHLIGHTS timed, coming hot on the heels of the greatest gold rush in • Enjoy a special trip by steam train on the Victorian Goldfields Australia’s history. The windfall from mining royalties was Railway, and the quaint Daylesford Spa Country Railway crucial in funding the construction of the country’s first • Sail, dine and sleep on the iconic PS Emmylou paddle main line railways. These branched out in the 1850s and steamer on the Murray River ‘60s to reach the ‘Pot of Gold’, the Murray River, at Echuca • Visit historic gold-rush towns, including Ballarat, Bendigo in 1864. Here, the riverboat trade was also booming and and Maldon the coming of the railway added another spoke to this • Stay in the historic former Railway Administration Office, already busy hub. Our special short adventure celebrates now the Quest Grand Hotel, in the heart of Melbourne this golden age of rail and river transport in the colony • Enjoy a sumptuous welcome dinner in Melbourne and of Victoria. It culminates in a kind of re-enactment of the farewell dinner at Ballarat’s historic Craig’s Hotel famous ‘meeting of the whistles’ at the Port of Echuca, • Explore Bendigo and Ballarat museums and townscapes where steam train and steam boat connected in a hail of on privately chartered vintage trams whistles echoing over the town and river – the sound that • Visit the gold rush open-air museum of Sovereign Hill in Ballarat and experience the newly re-launched light and once reminded one and all of the prosperity and enterprise sound show of their great state.