Machias Seal Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorbill: Species Information for Marine Special Protection Area Consultations

Natural England Technical Information Note TIN124 Razorbill: species information for marine Special Protection Area consultations The UK government has committed to identifying a network of Special Protection Areas (SPAs) in the marine environment by 2015. Natural England is responsible for recommending potential SPAs in English waters to Defra for classification. This and other related information notes have been written to provide further information to coastal and marine stakeholders about the bird species we are seeking to protect through Marine SPAs. For more information about the process for establishing marine SPAs see TIN120 Establishing Marine Special Protection Areas. Background The Birds Directive (EC Directive on the conservation of wild birds (79/409/EEC)) requires member states to identify SPAs for: rare or vulnerable bird species (as listed in Annex I of the Directive); and regularly occurring migratory bird species. Razorbills Alca torda are a regularly occurring migratory bird species in Europe. They are 37– 39 cm long with a wingspan of 63-68 cm1. Their typical lifespan is 13 years and the oldest Razorbill by Andy Brown reported individual was over 41 years old2. The majority of UK birds nest in the north and west of Scotland. In England, razorbills breed on Conservation Status coasts and islands in the north and south-west. UK amber-listed bird of conservation concern3. The largest English colony is at Flamborough Distribution and population Head and Bempton Cliffs in Yorkshire. Razorbills only breed along North Atlantic coasts, including the UK. Migration/movements Adults and dependent young disperse offshore The Seabird 2000 census lists the UK breeding from colonies in July – August, with adults population at 187,100 individuals, 20% of global becoming flightless during this period due to 4 population with 11,144 individuals breeding in moult. -

Norway Pout, Sandeel and North Sea Sprat

FINAL REPORT Initial assessment of the Norway sandeel, pout and North Sea sprat fishery Norges Fiskarlag Report No.: 2017-008, Rev 3 Date: January 2nd 2018 Certificate code: 251453-2017-AQ-NOR-ASI Report type: Final Report DNV GL – Business Assurance Report title: Initial assessment of the Norway sandeel, pout and North Sea sprat fishery DNV GL Business Assurance Customer: Norges Fiskarlag, Pirsenteret, Norway AS 7462 TRONDHEIM Veritasveien 1 Contact person: Tor Bjørklund Larsen 1322 HØVIK, Norway Date of issue: January 2nd 2018 Tel: +47 67 57 99 00 Project No.: PRJC -557210 -2016 -MSC -NOR http://www.dnvgl.com Organisation unit: ZNONO418 Report No.: 2017-008, Rev 3 Certificate No.: 251453-2017-AQ-NOR-ASI Objective: Assessment of the Norway sandeel, pout and North Sea sprat fishery against MSC Fisheries Standards v2.0. Prepared by: Verified by: Lucia Revenga Sigrun Bekkevold Team Leader and P2 Expert Principle Consultant Hans Lassen P1 Expert Geir Hønneland P3 Expert Stefan Midteide Project Manager Copyright © DNV GL 2014. All rights reserved. This publication or parts thereof may not be copied, reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, whether digitally or otherwise without the prior written consent of DNV GL. DNV GL and the Horizon Graphic are trademarks of DNV GL AS. The content of this publication shall be kept confidential by the customer, unless otherwise agreed in writing. Reference to part of this publication which may lead to misinterpretation is prohibited. DNV GL Distribution: ☒ Unrestricted distribution (internal and external) ☐ Unrestricted distribution within DNV GL ☐ Limited distribution within DNV GL after 3 years ☐ No distribution (confidential) ☐ Secret Rev. -

Population Status, Reproductive Ecology, and Trophic Relationships of Seabirds in Northwestern Alaska

POPULATION STATUS, REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY, AND TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS OF SEABIRDS IN NORTHWESTERN ALASKA by Alan M. Springer, Edward C. Murphy, David G. Roseneau, and Martha 1. Springer LGL Alaska Research Associates, Inc. P. O. BOX 80607 Fairbanks, Alaska 99708 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 460 April 1982 127 TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ I. SUMMARY OF OBJECTIVES, CONCLUSIONS, AND IMPLICATIONS WITH RESPECT TO OCS OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT. 131 II. INTRODUCTION. 131 III. CURRENT STATEOFKNOWLEDGE . 133 IV. STUDY AREAS. 133 Va. MURRE NUMBERS - METHODS. 135 VIa. MURRE NUMBERS-RESULTS.. 140 VIIa. MURRE NUMBERS-DISCUSSION . 145 VIIb. FOOD HABITS-METHODS. 162 VIIb . FOOD HABITS-RESULTS. 163 VIIb . FOOD HABITS -DISCUSSION. , . 168 VIIc . KITTIWAKES -METHODS. 203 VIIc . KITTIWAKES -RESULTS. 204 VIIC . KITTIWAKES -DISCUSSION. 206 VIId . OTHER SPECIES-METHODS.. 209 VId & VIId. OTHER SPECIES - RESULTS AND DISCUSSION . 209 VIII. CONCLUSIONS. 231 IX. NEEDS FORFUTURESTUDY . 232 x. LITEMITURECITED. 233 129 I. SUMMARY OF OBJECTIVES, CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS WITH REGARD TO OCS OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT A. Objectives The objective of RU 460 is to describe important components of the biology of seabirds in northern Alaska, including relationships among seabirds, their supporting food webs and the physical environment. To accomplish this objective we have concentrated on studies of thick-billed murres (Uris lomvia), common murres (U. aazge) and black-legged kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyZa), the most wide-spread, and among the most numerous, of all seabird species in the region. Moreover, murres and kittiwakes are easily studied compared to other species, and are sensitive indicators of environmental change. B: Conclusions Our principal conclusions are that numbers of murres at two major breeding colonies in northern Alaska are declining and that annual vari- ability is high in a variety of elements of murre and kittiwake breeding biology. -

Population Estimates and Temporal Trends of Pribilof Island Seabirds

POPULATION ESTIMATES AND TEMPORAL TRENDS OF PRIBILOF ISLAND SEABIRDS by F. Lance Craighead and Jill Oppenheim Alaska Biological Research P.O. BOX 81934 Fairbanks, Alaska 99708 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 628 November 1982 307 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dan Roby and Karen Brink, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, were especially helpful to us during our stay on St. George and shared their observations with us. Bob Day, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, also provided comparative data from his findings on St. George in 1981. We would like to thank the Aleut communities of St. George and St. Paul and Roger Gentry and other NMFS biologists on St. George for their hospitality and friendship. Bob Ritchie and Jim Curatolo edited an earlier version of this report. Mary Moran drafted the figures. Nancy Murphy and Patty Dwyer-Smith typed drafts of this report. Amy Reges assisted with final report preparation. Finally, we’d like to thank Dr. J.J. Hickey for initiating seabird surveys on the Pribi of Islands, which were the basis for this study. This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management through interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administra- tion, as part of the Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program. 308 TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. ● . ● . ● . ● . 308 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . ✎ . ● ✎ . ● . ● ● . ✎ . ● ● . 311 INTRODUCTION. ✎ . ● ✎ . ✎ . ✎ ✎ . ● ✎ ● . ● ✎ . 313 STUDY AREA. ● . ✎ ✎ . ✎ . ✎ ✎ . ✎ ✎ ✎ . , . ● ✎ . ● . 315 METHODS . ● . ✎ -

Grand Manan Channel – Southern Part NOAA Chart 13392

BookletChart™ Grand Manan Channel – Southern Part NOAA Chart 13392 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the 33-foot unmarked rocky patch known as Flowers Rock, 3.9 miles west- northwestward of Machias Seal Island, the channel is free and has a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration good depth of water. The tidal current velocity is about 2.5 knots and National Ocean Service follows the general direction of the channel. Daily predictions are given Office of Coast Survey in the Tidal Current Tables under Bay of Fundy Entrance. Off West Quoddy Head, the currents set in and out of Quoddy Narrows, forming www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov strong rips. Sailing vessels should not approach West Quoddy Head too 888-990-NOAA closely with a light wind. North Atlantic Right Whales.–The Bay of Fundy is a feeding and nursery What are Nautical Charts? area for endangered North Atlantic right whales (peak season: July through October) and includes the Grand Manan Basin, a whale Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show conservation area designated by the Government of Canada. (See North water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Atlantic Right Whales, chapter 3, for more information on right whales more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and and recommended measures to avoid collisions with whales.) efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial Southwest Head, the southern extremity of Grand Manan Island, is a ships that carry America’s commerce. -

Razorbill Alca Torda in North Norway

THE EFFECT OF PHYSICAL AND BIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS ON THE BREEDING SUCCESS OF RAZORBILLS (ALCA TORDA L. 1758) ON MACHIAS SEAL ISLAND, NB IN 2000 AND 2001 by Virgil D. Grecian Bachelor of Science (Hon), Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1996 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Graduate Academic Unit of Biology Supervisors: A.W. Diamond, Ph.D., Biology and Forestry & Environmental Management, J.W. Chardine, Ph.D., Canadian Wildlife Service Supervisory Committee: D.J. Hamilton, Ph.D., Mt Allison University Examining Board: This thesis is accepted. ………………………………………… Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada December, 2004 ABSTRACT The influence of various physical and biological parameters on the breeding biology of Razorbills (Alca torda) on Machias Seal Island (MSI) was studied in 2000 and 2001. The major predators (gulls) on seabird eggs and chicks on MSI are controlled, providing an unusual opportunity to study breeding biology in the virtual absence of predation. The timing of egg-laying was right skewed in both years. A complete survey 10-14 June 2000 of all Razorbill breeding habitat on MSI was combined with radio telemetry to estimate the total number of inaccessible breeding sites that may not have been counted. A corrected breeding pair estimate for MSI is 592 ± 17 pairs. Overall breeding success was 55% in 2000 and 59% in 2001. Most chicks that hatched also departed the island, so differences in breeding success were due chiefly to differences in hatching success. Adults breeding in burrows were more successful than adults in crevice and open nest sites. -

Comparative Breeding Biology of Guillemots Uria Spp. and Razorbills Alca Torda at a Colony in the Northwest Atlantic

Breeding biology ofGuillemots and Razorbills 121 121 Comparative breeding biology of Guillemots Uria spp. and Razorbills Alca torda at a colony in the Northwest Atlantic Vergelijkende broedbiologie van Zeekoeten en Alken op een kolonie in het Noorwestelijke Atlantische gebied J. Mark+Hipfner&Rachel Bryant Biopsychology Programme. Memorial University ofNewfoundland St. John's. NF. Canada AIB 3X9e-mail:[email protected] the Common Guillemots, We compared various aspectsof breedingbiology ofRazorbills, ” and Brünnich’s Guillemots (the “intermediate auks) at the Gannet Islands, Labrador. Canada, in 1997. In all three species, layingfollowed a strongly right-skewedpattern, In with median laying dates falling within a narrow window between 27-29 June. and comparison topreviousyears, laying was late, relatively synchronous among species. 2 in Razorbills 35 than in either Incubation periods were days longer (median days) guillemot species (33 days), whereas Common Guillemots had longer nestling periods (mean 24 days) than Razorbills (19 days) or Brünnich’s Guillemots (20 days). In all species, there was a tendency for late-laying pairs to contract their breeding periods, in mainly by reducing the duration of the nestling period. Breeding success was high Razorbills (73%) and Common Guillemots (85%), but low in Brünnich’s Guillemots Brünnich Guillemots (51%), largely due to low hatching success. Late-breeding ’s were little this in the other more likely tofail than were earlypairs, but there was indication of two species. Seasonal patterns of colony attendance suggested that there were many young, pre-breeding Brünnich’s Guillemots and Razorbills present; populations of these in since species appear to be faring well at this colony. -

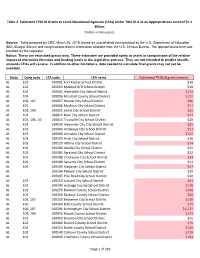

Page 1 of 283 State Cong Code LEA Code LEA Name Estimated FY2018

Table 2. Estimated FY2018 Grants to Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) Under Title IV-A at an Appropriations Level of $1.1 Billion Dollars in thousands Source: Table prepared by CRS, March 26, 2018, based on unpublished data provided by the U.S. Department of Education (ED), Budget Service and congressional district information available from the U.S. Census Bureau. The appropriations level was provided by the requester. Notice: These are estimated grants only. These estimates are provided solely to assist in comparisons of the relative impact of alternative formulas and funding levels in the legislative process. They are not intended to predict specific amounts LEAs will receive. In addition to other limitations, data needed to calculate final grants may not yet be available. State Cong code LEA code LEA name Estimated FY2018 grant amount AL 102 100001 Fort Rucker School District $10 AL 102 100003 Maxwell AFB School District $10 AL 104 100005 Albertville City School District $153 AL 104 100006 Marshall County School District $192 AL 106, 107 100007 Hoover City School District $86 AL 105 100008 Madison City School District $57 AL 103, 106 100011 Leeds City School District $32 AL 104 100012 Boaz City School District $41 AL 103, 106, 107 100013 Trussville City School District $20 AL 103 100030 Alexander City City School District $83 AL 102 100060 Andalusia City School District $51 AL 103 100090 Anniston City School District $122 AL 104 100100 Arab City School District $26 AL 105 100120 Athens City School District $54 AL 104 100180 Attalla -

Common Murre •.• Thick-Billed Murre

j. Field Ornithol., 54(3):266-274 THE FLEDGING OF COMMON AND THICK-BILLED MURRES ON MIDDLETON ISLAND, ALASKA BY SCOTT A. HATCH Three speciesof alcids,Common and Thick-billed murres (Uria aalge and U. lornvia)and the Razorbill (Alca torda),have post-hatchingdevel- opmental patterns intermediate to precocialand semi-precocialmodes (Sealy1973). The youngleave their cliff nestsites at aboutone quarter of adult weight and completetheir growth at sea.At departure, an event here looselyreferred to as "fledging," neither primary nor secondary flight feathersare grown, but well-developedwing covertsenable lim- ited, descendingflight. The adaptivesignificance of thispattern maybe that leadingthe young to distantfeeding areasis more efficientthan lengthy foraging flights by adultsonce the chicks'energetic requirements exceed some critical level (Sealy 1973, Birkhead 1977). The risk to predation is probably greater in exposednest sitesthan at sea, contributing further to the selectiveadvantage of earlyfledging (Cody 1971, Birkhead1977). Given these constraints,however, larger chickswould be expected to better survivethe rigorsof fledging,increased activity at sea,and the vagaries of weather. Hedgren (1981) analyzed278 recoveriesof CommonMurres banded as fledglingsand found no significantrelationship between fledging weight and subsequentsurvival. This result is paradoxicalin view of a strong expectationto the contrary and evidencethat such an effect occursin other speciesof birds (Perrins 1965, Perrinset al. 1973, O'Con- ner 1976). Hedgren suggestedthe nestlingperiod of murres,averaging about3 weeks,is determinednot by a thresholdin bodysize, but by the relativelyconstant time requiredto completefeather growth.Birkhead (1977) alsoemphasized the need for chicksto attain a critical weight: wing-arearatio prior to fledging. Clearly, however,body weight and feather developmentare not mutuallyexclusive factors affecting fledg- ling survival. -

Alcid Identification in Massachusetts

ALCID IDENTIFICATION IN MASSACHUSETTS by Richard R. Veit, Tuckernuck The alcldae, a northern circvimpolar family of sesbirds, are memhers of the order Charadrilformes and thus most closely related to the gulls, skuas, and shorehirds. All alcids have approximately elliptical bodies and much reduced appendages, adaptations for insulation as well as a streamlined trajectory under water. Their narrow flipperlike wings are modified to reduce drag durlng underwater propulsión, and are, therefore, comparatively inefficient for flight. Razorbills, murres, and puffins feed predominately on fish, such as the sand launce, capelin, Arctic cod, herring, and mackerel. The Dovekie, by far the smallest Atlantic alcid, eats zooplankton exclusively, such as the superabundant "krill." The Black Guillemot, unique.in its con- finement to the shallow littoral zone, feeds largely on rock eels or gunnel. As with many pelagic birds, the alcids' dependence on abundant marine food restricts them to the productive vaters of the high latitudes. Bio- logical productivity of the oceans increases markedly towards the poles, largely because the low surface temperaturas there maintain convection currents which serve to raise large quantities of dissolved mineral nu triente to the siirface. The resultant high concentration of nutriente near the surface of polar seas supports enormous populations of plankton and, ultimately, the fish upon which the largar alcids feed. Alcids are comparatively weak flyers and are not regularly migratory, but rather disperse from their breeding ranga only when forced to do so by freezing waters or food scarcity. Massachusetts lies at the periphery of the ranges of these birds, with the exception of the Razorbill. It i& only under exceptional circumstances, such as southward irruptions coupled with strong northeasterly storms that substantial numbers of alcids are observad along the Massachusetts coastline. -

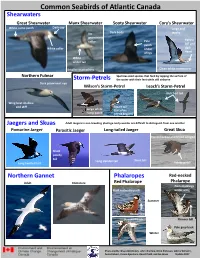

Common Seabirds of Atlantic Canada

Common Seabirds of Atlantic Canada Shearwaters Great Shearwater Manx Shearwater Sooty Shearwater Cory’s Shearwater White rump patch dark Dark cap Large and cap Dark body stocky No dark prominent head Yellow collar Pale patch bill and dark dark White collar under yellowhead belly wings bill White broad under tail wings Smaller than others Clean white underparts Northern Fulmar Sparrow-sized species that feed by tapping the surface of Storm-Petrels the water with their feet while still airborne Dark prominent eye Wilson’s Storm-Petrel Leach’s Storm-Petrel Notched tail Wing beat shallow and stiff Square tail Large white (feet often rump patch extend beyond) Jaegers and Skuas Adult Jaegers in non-breeding plumage and juveniles are difficult to distinguish from one another Pomarine Jaeger Parasitic Jaeger Long-tailed Jaeger Great Skua Hunchbacked and broad winged Short pointy tail Long slender tail Short bill Long twisted tail White patch Northern Gannet Phalaropes Red-necked Adult Immature Red Phalarope Phalarope Dark markings Bold red underparts under wing Summer Thicker bill White chin Streaked back Thinner bill Pale grey back Winter Photo credits: Bruce Mactavish, John Chardine, Brian Patteson, Sabina Wilhelm, Anna Calvert, Carina Gjerdrum, Dave Fifield, and Ian Jones. Update 2017 Common Seabirds of Atlantic Canada Black wing-tipped Gulls Herring Gull Great Black-backed Gull Black-legged Kittiwake Adult Adult Has brownish Breeding adult Winter adult head in winter Dark patch Marbled More uniform behind underwing brown than eye coverts -

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas Summary of a Conference Held January 12–13, 2016 Volume Editors: Rafiq Dossani, Scott Warren Harold Contributing Authors: Michael S. Chase, Chun-i Chen, Tetsuo Kotani, Cheng-yi Lin, Chunhao Lou, Mira Rapp-Hooper, Yann-huei Song, Joanna Yu Taylor C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF358 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: Detailed look at Eastern China and Taiwan (Anton Balazh/Fotolia). Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Disputes over land features and maritime zones in the East China Sea and South China Sea have been growing in prominence over the past decade and could lead to serious conflict among the claimant countries.