Brazil's Parliament and Other Political Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haiti: Real Progress, Real Fragility a Special Report by the Inter-American Dialogue and the Canadian Foundation for the Americas

November 2007 Haiti: Real Progress, Real Fragility A Special Report by the Inter-American Dialogue and the Canadian Foundation for the Americas Haitian President René Préval says that working with the United Nations and other his country no longer deserves its “failed international partners – including a core state” stigma, and he is right. Haiti’s recent group of Latin American countries, the progress is real and profound, but it is United States and Canada – has achieved jeopardized by continued institutional modest but discernible progress in improv- dysfunction, including the government’s ing security and establishing, at least mini- inexperience in working with Parliament. mally, a democratic governing structure. There is an urgent need to create jobs, But institutions, both public and private, attract investment, overhaul and expand are woefully weak, and there has not been Haiti access to basic social services, and achieve significant economic advancement. Unem- tangible signs of economic recovery. Now ployment remains dangerously high and a that the United Nations has extended its majority of the population lives in extreme peacekeeping mandate until October 2008, poverty. Still, Haiti should be viewed today the international community must seek with guarded optimism. There is a real pos- ways to expand the Haitian state’s capacity sibility for the country to build towards a to absorb development aid and improve the better future. welfare of the population. The alternative could be dangerous backsliding. The Good News President René Préval was inaugurated in Haiti is beginning to emerge from the May 2006 following presidential and parlia- chaos that engulfed it in recent years. -

Congressional Record—Senate S8015

January 1, 2021 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S8015 Whereas, in February 2019, the Department (B) guarantee unfettered humanitarian ac- (C) support credible efforts to address the of State announced that it would withhold cess and assistance to the Northwest and root causes of the conflict and to achieve some security assistance to Cameroon, in- Southwest regions; sustainable peace and reconciliation, pos- cluding equipment and training, citing cred- (C) exercise restraint and ensure that po- sibly involving an independent mediator, and ible allegations of human rights violations litical protests are peaceful; and efforts to aid the economic recovery of and by state security forces and a lack of inves- (D) establish a credible process for an in- fight coronavirus in the Northwest and tigation, accountability, and transparency clusive dialogue that includes all relevant Southwest regions; by the Government of Cameroon in response; stakeholders, including from civil society, to (D) support humanitarian and development Whereas, on December 26, 2019, the United achieve a sustainable political solution that programming, including to meet immediate States terminated the designation of Cam- respects the rights and freedoms of all of the needs, advance nonviolent conflict resolu- eroon as a beneficiary under the African people of Cameroon; tion and reconciliation, promote economic Growth and Opportunity Act (19 U.S.C. 3701 (3) affirms that the United States Govern- recovery and development, support primary et seq.) because ‘‘the Government of -

Toolkit: Citizen Participation in the Legislative Process

This publication was made possible with financial support from the Government of Canada. About ParlAmericas ParlAmericas is the institution that promotes PARLIAMENTARY DIPLOMACY in the INTER-AMERICAN system ParlAmericas is composed of the 35 NATIONAL LEGISLATURES from North, Central and South America and the Caribbean ParlAmericas facilitates the exchange of parliamentary BEST PRACTICES and promotes COOPERATIVE POLITICAL DIALOGUE ParlAmericas mainstreams GENDER EQUALITY by advocating for women’s political empowerment and the application of a gender lens in legislative work ParlAmericas fosters OPEN PARLIAMENTS by advancing the principles of transparency, accountability, citizen participation, ethics and probity ParlAmericas promotes policies and legislative measures to mitigate and adapt to the effects ofCLIMATE CHANGE ParlAmericas works towards strengthening democracy and governance by accompanying ELECTORAL PROCESSES ParlAmericas is headquartered in OTTAWA, CANADA Table of Contents Toolkit Co-creation Plan 6 Contributors 8 Introduction 9 Objective 9 Using this Toolkit 9 Defining Citizen Participation 10 Importance of Citizen Participation 10 Participation Ladder 11 Overview of Citizen Participation in the Legislative Process 12 Developing a Citizen Participation Strategy 15 Principles of Citizen Participation 16 Resources to Support Citizen Participation 17 Educating Citizens and Promoting Participation 18 Awareness Raising Programs and Campaigns 18 Citizen Participation Offices and Communications Departments 19 Parliamentary Websites -

M.JJ WORKING PAPERS in ECONOMIC HISTORY

IIa1 London School of Economics & Political Science m.JJ WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY LATE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN A REGIONAL CONCEPT Domingos Giroletti, Max-Stephen Schulze, Caries Sudria Number: 24/94 December 1994 r Working Paper No. 24/94 Late Economic Development in a Regional Context Domingos GiroIetti, Max-Stephan Schulze, CarIes Sudri3 ct>Domingos Giroletti, Max-Stephan Schulze December 1994 Caries Sudria Economic History Department, London School of Economics. Dorningos Giroletti, Max-Stephan Schulze, Caries Sudriii clo Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE United Kingdom Phone: + 44 (0) 171 955 7084 Fax: +44 (0)1719557730 Additional copies of this working paper are available at a cost of £2.50. Cheques should be made payable to 'Department of Economic History, LSE' and sent to the Departmental Secretary at the address above. Entrepreneurship in a Later Industrialising Economy: the case of Bernardo Mascarenhas and the Textile Industry in Minas Gerais, Brazil 1 Domingos Giroletti, Federal University of Minas Gerais and Visiting Fellow, Business History Unit, London School of Economics Introduction The modernization of Brazil began in the second half of the last century. Many factors contributed to this development: the transfer of the Portuguese Court to Rio de Janeiro and the opening of ports to trade with all friendly countries in 1808; Independence in 1822; the development of coffee production; tariff reform in 1845; and the suppression of the trans-Atlantic slave trade around 1850, which freed capital for investments in other activities. Directly and indirectly these factors promoted industrial expansion which began with the introduction of modern textile mills. -

Brazil Ahead of the 2018 Elections

BRIEFING Brazil ahead of the 2018 elections SUMMARY On 7 October 2018, about 147 million Brazilians will go to the polls to choose a new president, new governors and new members of the bicameral National Congress and state legislatures. If, as expected, none of the presidential candidates gains over 50 % of votes, a run-off between the two best-performing presidential candidates is scheduled to take place on 28 October 2018. Brazil's severe and protracted political, economic, social and public-security crisis has created a complex and polarised political climate that makes the election outcome highly unpredictable. Pollsters show that voters have lost faith in a discredited political elite and that only anti- establishment outsiders not embroiled in large-scale corruption scandals and entrenched clientelism would truly match voters' preferences. However, there is a huge gap between voters' strong demand for a radical political renewal based on new faces, and the dramatic shortage of political newcomers among the candidates. Voters' disillusionment with conventional politics and political institutions has fuelled nostalgic preferences and is likely to prompt part of the electorate to shift away from centrist candidates associated with policy continuity to candidates at the opposite sides of the party spectrum. Many less well-off voters would have welcomed a return to office of former left-wing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010), who due to a then booming economy, could run social programmes that lifted millions out of extreme poverty and who, barred by Brazil's judiciary from running in 2018, has tried to transfer his high popularity to his much less-known replacement. -

Corporate Dependence in Brazil's 2010 Elections for Federal Deputy*

Corporate Dependence in Brazil's 2010 Elections for Federal Deputy* Wagner Pralon Mancuso Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil Dalson Britto Figueiredo Filho Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Brazil Bruno Wilhelm Speck Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil Lucas Emanuel Oliveira Silva Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Brazil Enivaldo Carvalho da Rocha Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Brazil What is the profile of candidates whose electoral campaigns are the most dependent on corporate donations? Our main objective is to identify factors that help explaining the level of corporate dependence among them. We answer this question in relation to the 2010 elections for federal deputy in Brazil. We test five hypotheses: 01. right-wing party candidates are more dependent than their counterparts on the left; 02. government coalition candidates are more dependent than candidates from the opposition; 03. incumbents are more dependent on corporate donations than challengers; 04. businesspeople running as candidates receive more corporate donations than other candidates; and 05. male candidates are more dependent than female candidates. Methodologically, the research design combines both descriptive and multivariate statistics. We use OLS regression, cluster analysis and the Tobit model. The results show support for hypotheses 01, 03 and 04. There is no empirical support for hypothesis 05. Finally, hypothesis 02 was not only rejected, but we find evidence that candidates from the opposition receive more contributions from the corporate sector. Keywords: Corporate dependence; elections; campaign finance; federal deputies. * http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1981-38212016000300004 For data replication, see bpsr.org.br/files/archives/Dataset_Mancuso et al We thank the editors for their careful work and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. -

Haiti: Concerns After the Presidential Assassination

INSIGHTi Haiti: Concerns After the Presidential Assassination Updated July 19, 2021 Armed assailants assassinated Haitian President Jovenel Moïse in his private home in the capital, Port-au- Prince, early on July 7, 2021 (see Figure 1). Many details of the attack remain under investigation. Haitian police have arrested more than 20 people, including former Colombian soldiers, two Haitian Americans, and a Haitian with long-standing ties to Florida. A Pentagon spokesperson said the U.S. military helped train a “small number” of the Colombian suspects in the past. Protesters and opposition groups had been calling for Moïse to resign since 2019. The assassination’s aftermath, on top of several preexisting crises in Haiti, likely points to a period of major instability, presenting challenges for U.S. policymakers and for congressional oversight of the U.S. response and assistance. The Biden Administration requested $188 million in U.S. assistance for Haiti in FY2022. Congress has previously held hearings, and the cochair of the House Haiti Caucus made a statement on July 7 suggesting reexaminations of U.S. policy options on Haiti. Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov IN11699 CRS INSIGHT Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Congressional Research Service 2 Figure 1. Haiti Source: CRS. Succession. Who will succeed Moïse is unclear, as is the leadership of the Haitian government. In the assassination’s immediate aftermath, interim Prime Minister Claude Joseph was in charge, recognized by U.S. and U.N. officials, and said the police and military were in control of Haitian security. Joseph became interim prime minister in April 2021. -

The November 2011 Elections in Nicaragua: a Study Mission Report of the Carter Center

The November 2011 Elections in Nicaragua Study Mission Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. The November 2011 Elections in Nicaragua: A Study Mission Report of the Carter Center THE NOVEMBER 2011 ELECTIONS IN NICARAGUA: A STUDY MISSION REPORT OF THE CARTER CENTER OVERVIEW On November 6, 2011 Nicaragua held general elections for president and vice president, national and departmental deputies to the National Assembly, and members of the Central American Parliament. Fraudulent local elections in 2008, a questionable Supreme Court decision in October 2009 to permit the candidacy of incumbent President Daniel Ortega, and a presidential decree in January 2010 extending the Supreme Electoral Council (CSE) magistrates in office after their terms expired provided the context for a deeply flawed election process. Partisan election preparations were followed by a non-transparent election day and count. The conditions for international and domestic election observation, and for party oversight, were insufficient to permit verification of compliance with election procedures and Nicaraguan electoral law, and numerous anomalies cast doubt on the quality of the process and honesty of the vote count. The most important opposition party rejected the election as fraudulent but took its seats in the legislature. Nicaragua’s Supreme Electoral Council dismissed opposition complaints and announced that President Daniel Ortega had been re-elected to a third term. In addition, the official results showed that Ortega’s Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) party had won enough legislative seats both to reform articles of the constitution (requires a 60% majority) and to call a constituent assembly to write a new constitution (requires 66%). -

Responsabilidade Civil E Solidariedade Social: Potencialidades De Um Diálogo 393

Responsabilidade civil e solidariedade social: potencialidades de um diálogo 393 Responsabilidade civil e solidariedade social: potencialidades de um diálogo Nelson Rosenvald1 Procurador de Justiça do Ministério Público de Minas Gerais Felipe Braga Netto2 Procurador da República Sumário: 1. Uma palavra introdutória: olhando para trás. 1.1. O individualismo jurídico e as liberdades clássicas do direito civil. 1.2. A tradição patrimonialista que historicamente permeou os institutos civis. 2. A revitalização do direito civil em múltiplas dimensões: o es- pectro normativo da dignidade e da solidariedade social. 3. Os ciclos evolutivos da responsabilidade civil: entre velhas estruturas e novas funções. 3.1. Os degraus da responsabilidade civil: um olhar através dos ciclos históricos. 4. Proposições conclusivas. 1. Uma palavra introdutória: olhando para trás Para bem compreendermos o novo, é essencial conhecer o que havia antes. Seja para evitar o apego anacrônico a modelos teóricos que já não nos servem, seja para evitar que nos deixemos seduzir ir- refletidamente pela (leviana) novidade. O novo não é necessariamente sinônimo de qualidade. O autenticamente novo é um fiel depositário 1 Pós-Doutor em Direito Civil na Universidade de Roma Tre (Itália). Professor Visitante na Oxford Uni- versity (Inglaterra). Professor Pesquisador na Universidade de Coimbra (Portugal). Doutor e Mestre em Direito Civil pela PUC-SP. Bacharel em Direito pela Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Membro do European Law Institute (ELI). Membro da Society of Legal Scholars (Inglaterra). Membro do Comitê Científico da Revista Actualidad Juridica Iberoamericana (Espanha). Coautor do Curso de Direito Civil, do Novo Tratado de Responsabilidade Civil, e do Volume Único de Direito Civil. -

Brazilian Images of the United States, 1861-1898: a Working Version of Modernity?

Brazilian images of the United States, 1861-1898: A working version of modernity? Natalia Bas University College London PhD thesis I, Natalia Bas, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Abstract For most of the nineteenth-century, the Brazilian liberal elites found in the ‘modernity’ of the European Enlightenment all that they considered best at the time. Britain and France, in particular, provided them with the paradigms of a modern civilisation. This thesis, however, challenges and complements this view by demonstrating that as early as the 1860s the United States began to emerge as a new model of civilisation in the Brazilian debate about modernisation. The general picture portrayed by the historiography of nineteenth-century Brazil is still today inclined to overlook the meaningful place that U.S. society had from as early as the 1860s in the Brazilian imagination regarding the concept of a modern society. This thesis shows how the images of the United States were a pivotal source of political and cultural inspiration for the political and intellectual elites of the second half of the nineteenth century concerned with the modernisation of Brazil. Drawing primarily on parliamentary debates, newspaper articles, diplomatic correspondence, books, student journals and textual and pictorial advertisements in newspapers, this dissertation analyses four different dimensions of the Brazilian representations of the United States. They are: the abolition of slavery, political and civil freedoms, democratic access to scientific and applied education, and democratic access to goods of consumption. -

Nicaragua: in Brief

Nicaragua: In Brief Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs September 14, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44560 Nicaragua: In Brief Summary This report discusses Nicaragua’s current politics, economic development and relations with the United States and provides context for Nicaragua’s controversial November 6, 2016, elections. After its civil war ended, Nicaragua began to establish a democratic government in the early 1990s. Its institutions remained weak, however, and they have become increasingly politicized since the late 1990s. Current President Daniel Ortega was a Sandinista (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional, FSLN) leader when the Sandinistas overthrew the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza in 1979. Ortega was elected president in 1984. An electorate weary of war between the government and U.S.-backed contras denied him reelection in 1990. After three failed attempts, he won reelection in 2006, and again in 2011. He is expected to win a third term in November 2016 presidential elections. As in local, municipal, and national elections in recent years, the legitimacy of this election process is in question, especially after Ortega declared that no domestic or international observers would be allowed to monitor the elections and an opposition coalition was effectively barred from running in the 2016 elections. As a leader of the opposition in the legislature from 1990 to 2006, and as president since then, Ortega slowly consolidated Sandinista—and personal—control over Nicaraguan institutions. As Ortega has gained power, he reputedly has become one of the country’s wealthiest men. His family’s wealth and influence have grown as well, inviting comparisons to the Somoza family dictatorship. -

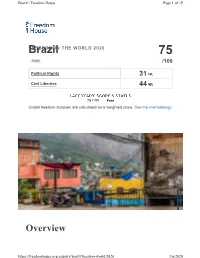

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process.