Subordination and Resistance on a Global Arts Stage Nancy M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stay Local in Venice 2-Night Pre-Voyage Land Journey Program Begins In: Venice Program Concludes In: Venice

Stay Local in Venice 2-Night Pre-voyage Land Journey Program Begins in: Venice Program Concludes in: Venice Available on these Sailings: Journey 09-Apr-2022 Pursuit 16-Apr-2022 Journey 07-May-2022 Onward 13-May-2022 Onward 21-May-2022 Onward 11-Jun-2022 Onward 18-Jun-2022 Journey 18-Jul-2022 Journey 17-Aug-2022 Onward 27-Aug-2022 Journey 06-Oct-2022 Quest 07-Oct-2022 Pursuit 10-Oct-2022 Onward 10-Oct-2022 Pursuit 17-Oct-2022 Journey 15-Apr-2023 Journey 22-Apr-2023 Onward 06-May-202 Onward 13-May-2023 Onward 10-Jun-2023 Onward 17-Jun-2023 Onward 20-Jul-2023 Quest 26-Jul-2023 Quest 04-Aug-2023 Onward 22-Aug-2023 Onward 10-Sep-2023 Onward 04-Oct-2023 Quest 04-Oct-2023 Pursuit 07-Oct-2023 Journey 07-Oct-2023 Quest 12-Oct-2023 Pursuit 14-Oct-2023 Call 1-855-AZAMARA to reserve your Land Journey Venice is—without question—one of the most beautiful and unique cities in the world. Its iconic canals infuse the city with an air of antiquity, reinforced by the presence of ornate palazzos that go back centuries. Your stay includes a walking tour of the city that showcases the great Doge’s Palace and the Bridge of Sighs, so coined because it once led unfortunate souls to their fate in the prison. You’ll also enjoy skip-the-line entrance to Venice’s most famous site, St. Mark’s Basilica. Later, when the sun sets, enjoy a quintessential gondola ride. All Passport details should be confirmed at the time of booking. -

Suspension Bridges

Types of Bridges What are bridges used for? What bridges have you seen in real life? Where were they? Were they designed for people to walk over? Do you know the name and location of any famous bridges? Did you know that there is more than one type of design for bridges? Let’s take a look at some of them. Suspension Bridges A suspension bridge uses ropes, chains or cables to hold the bridge in place. Vertical cables are spaced out along the bridge to secure the deck area (the part that you walk or drive over to get from one side of the bridge to the other). Suspension bridges can cover large distances. Large pillars at either end of the waterways are connected with cables and the cables are secured, usually to the ground. Due to the variety of materials and the complicated design, suspension bridges are very expensive to build. Suspension Bridges The structure of suspension bridges has changed throughout the years. Jacob’s Creek Bridge in Pennsylvania was built in 1801. It was the first suspension bridge to be built using wrought iron chain suspensions. It was 21 metres long. If one single link in a chain is damaged, it weakens the whole chain which could lead to the collapse of the bridge. For this reason, wire or cable is used in the design of suspension bridges today. Even though engineer James Finlay promised that the bridge would stay standing for 50 years, it was damaged in 1825 and replaced in 1833. Suspension Bridges Akashi Kaiko Bridge, Japan The world’s longest suspension bridge is the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge in Japan. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal)

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal) Night shot of the Canal Grande or Grand Canal of Venice, Italy The Canal Grande and the Canale della Giudecca are the two most important waterways in Venice. They undoubtedly fall into the category of one of the premier tourist attractions in Venice. The Canal Grande separates Venice into two distinct parts, which were once popularly referred to as 'de citra' and 'de ultra' from the point of view of Saint Mark's Basilica, and these two parts of Venice are linked by the Rialto bridge. The Rialto Bridge is the most ancient bridge in Venice.; it is completely made of stone and its construction dates back to the 16th century. The Canal Grande or the Grand Canal forms one of the major water-traffic corridors in the beautiful city of Venice. The most popular mode of public transportation is traveling by the water bus and by private water taxis. This canal crisscrosses the entire city of Venice, and it begins its journey from the lagoon near the train station and resembles a large S-shape through the central districts of the "sestiere" in Venice, and then comes to an end at the Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute near the Piazza San Marco. The major portion of the traffic of the city of Venice goes along the Canal Grande, and thus to avoid congestion of traffic there are already three bridges – the Ponte dei Scalzi, the Ponte dell'Accademia, and the Rialto Bridge, while another bridge is being constructed. The new bridge is designed by Santiago Calatrava, and it will link the train station to the Piazzale Roma. -

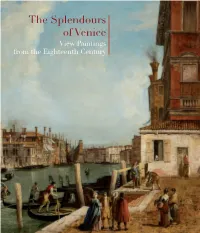

The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century the Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century

The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century Valentina Rossi and Amanda Hilliam DE LUCA EDITORI D’ARTE The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century Lampronti Gallery 1-24 December 2014 9.30 - 6 pm Exhibition curated by Acknowledgements Amanda Hilliam Marcella di Martino, Emanuela Tarizzo, Barbara De Nipoti, the staff of Valentina Rossi Itaca Transport, the staff of Simon Jones Superfreight. Catalogue edited by Amanda Hilliam Valentina Rossi Photography Mauro Coen Matthew Hollow LAMPRONTI GALLERY 44 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6DD Via di San Giacomo 22 00187 Roma [email protected] [email protected] p. 2: Francesco Guardi, The lagoon with the Forte di S. Andrea, cat. 20, www.cesarelampronti.com detail his exhibition and catalogue commemorates the one-hundred-year anniversary of Lampronti Gallery, founded in 1914 by my Grandfather and now one of the foremost galleries specialising in Italian Old TMaster paintings in the United Kingdom. We have, over the years, developed considerable knowledge and expertise in the field of vedute, or view paintings, and it therefore seemed fitting that this centenary ex- hibition be dedicated to our best examples of this great tradition, many of which derive from important pri- vate collections and are published here for the first time. More precisely, the exhibition brings together a fine selection of views of Venice, a city whose romantic canals and quality of light were never represented with greater sensitivity or technical brilliance than during the eigh- teenth century. -

Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011

Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM Last updated Friday, February 11, 2011 Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. File Name: 2866-103.jpg Title Title Section Raw File Name: 2866-103.jpg Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 Display Order Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper 148.5 x 264.2 -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

Popsicle Stick Bridge Lesson Plan – Unit V ARCH BRIDGE

PENSACOLA BAY BRIDGE REPLACEMENT PROJECT Popsicle Stick Bridge Lesson Plan – Unit V ARCH BRIDGE Objective: “Arch Bridges.” After this lesson, students should be able to do the following: • discuss different types of arch bridge designs; • understand how the arch bridge supports load (dead and live) and how the forces are applied; and • determine the elements of an arch bridge. Summary: Through a PowerPoint presentation, students will learn about arch bridges and how they manage the natural forces of compression and tension. They will also find out about the elements important to arch bridge construction. Materials: PowerPoint presentation, 2 2” x 12” strips of cardboard per student, and a stack of books (to test bridge strength). Page 1 Pensacola Bay Bridge Popsicle Stick Bridge Lesson Plan MIDDLE SCHOOL ACADEMIC STANDARDS Objectives: SC.6.P.13.1 SC.8.N.1.1 Investigate and describe types of forces Define a problem from the eighth grade including contact forces and forces acting curriculum using appropriate reference at a distance, such as electrical, magnet- materials to support scientific understanding, ic, and gravitational. plan and carry out scientific investigations of various types, such as systematic observations or experiments, identify SC.6.P.13.2 variables, collect and organize data, interpret data in charts, tables, and graphics, analyze Explore the Law of Gravity by recognizing information, make predictions, and defend that every object exerts gravitational force conclusions. on every other object and that the force depends on how much mass the objects have and how far apart they are. SC.8.N.1.5 Analyze the methods used to develop a SC.7.P.11.2 scientific explanation as seen in different fields of science. -

Introducing Venice

INTRODUCING VENICE A fleet of gondoliers, among others, navigates the riches of the Grand Canal (p125) From the look of it, you'd think Venice spent all its time primping. Bask in the glory of Grand Canal pal- aces, but make no mistake: this city's a powerhouse. You may have heard that Venice is an engineering marvel, with marble cathedrals built atop ancient posts driven deep into the barene (mud banks) – but the truth is that this city is built on sheer nerve. Reasonable people might blanch at water approaching their doorsteps and flee at the first sign of acqua alta (high tide). But reason can’t compare to Venetian resolve. Instead of bailing out, Venetians have flooded the world with voluptuous Venetian-red paintings and wines, music, Marco Polo spice-route flavours, and bohemian-chic fashion. And they’re not done yet. VENICE LIFE With the world’s most artistic masterpieces per square kilometre, you’d think the city would take it easy, maybe rest on its laurels. But Venice refuses to retire from the inspiration business. In narrow calli (alleyways), you’ll glimpse artisans hammering out shoes crested like lagoon birds, cooks whipping up four-star dishes on single-burner hotplates, and musicians lugging 18th-century cellos to riveting baroque concerts played with punk-rock bravado. As you can see, all those 19th-century Romantics got it wrong. Venice is not destined for genteel decay. Billion- aire benefactors and cutting-edge biennales are filling up those ancient palazzi (palaces) with restored masterpieces and eyebrow-raising contemporary art and architecture, and back-alley galleries and artisan showrooms are springing up in their shadows. -

Venice in a Day Walking Tour

SHORE EXCURSION BROCHURE FROM THE PORT OF VENICE DURATION 10 hr Venice in a Day TOUR DIFFICULTY Walking Tour EASY MEDIUM HARD our enchanting tour of Venice will begin with a boat tour of the Grand YCanal that will take you from your cruise ship to St. Mark’s Square. Learn about the many prestigious palaces, churches and gardens that line the banks of this most unique street of the world. You will visit the Cathedral of Venice, St. Mark’s Basilica, with the richness of its marbles and mosaics; the Doge’s palace, the fourteenth century building from where the ancient Venetian republic exerted the control over the city. Passing through the famous Bridge of Sighs you will reach the Prisons Palace. On your way to lunch, you will experience a private gondola serenade with live musicians on board through the enchanting maze of canals. Your tour will continue with a walk through the narrow streets (calli) and small squares (campi) to see the famed La Fenice Theatre. The tour continues with a visit to the gothic church of Frari (Franciscan friars) with paintings of Bellini, Tiziano and sculptures of Canova. The Rialto bridge and its market will give a perfect farewell to the clients for the end of the tour. BUTIQUE TOURS OTHER INFORMATION Highlights Of Your Excursion • This Venice Port shore excursion to Venice departs from and returns to your cruise ship. • Private boat and Captain • This is a Private Tour • Licensed Expert English-speaking guide • At times St. Mark’s Basilica is closed due to high • Private motor-launch for tour of the Grand Canal water or religious ceremonies. -

Venice Italy Venice

21026 Venice Italy Venice Built on over 100 islands in a marshy lagoon at the edge of the Today the city is facing major challenges including gradual Adriatic Sea, Venice has a skyline that rises from the water to subsidence, flooding, and problems caused by its popularity as create a unique architectural experience. There are no roadways a tourist destination. More than 60,000 people visit Venice each or cars in the historic city; instead 177 canals crossed by over day—more than the population of the city itself—putting pressure 400 bridges give access to innumerable narrow, mazelike alleys on the city to accommodate these guests while maintaining its and squares. unique nature and identity. While the origin of the city dates back over 1500 years, the golden age of Venice occurred during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance periods when it became one of the most powerful republics in the eastern Mediterranean. Rialto Bridge The Rialto Bridge (Ponte di Rialto) spans the Grand Canal at the heart of the historic city. Built between 1588 and 1591, it replaced earlier wooden bridges that had linked the districts of San Marco and San Polo since the 12th century. When the last wooden bridge collapsed in 1524, several projects were considered before the city authorities requested plans for a stone bridge in 1551. The architect Antonio da Ponte competed with illustrious competitors such as Michelangelo and Palladio Rialto Bridge before winning the contract. His single span design with a 24 ft. (7.5 m) arch included three [ “To build a city where it is walkways: two along the outer edges and a wider central walkway between two rows of small shops. -

Points-West 1995.09.Pdf

CaruxoAR oF Evrxrs September - Open 8 am to 8 pm October - Open 8 am to 5 pm November - Open 10 am to 3 pm SEPTEMBER Native American Day school program. Buffalo Bill Art Show public program. Artist Donald "Putt" Putman will speak on "What Motivates the Artist?" 3 pm. Historical Center Coe Auditorium. Cody Country Chamber of Commerce's Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale. 5 pm. Cody Country Art League, across Sheridan Avenue from the Historical Center. OCTOBER 19th Annual Patrons Ball. Museum closes to the public at 4 pm. Museum Tiaining Workshop. Western Design Conference seminar sessions. Patrons' Children s Wild West Halloween Party. 3-5 pm. Buffalo Bill Celebrity Shootout, Cody Shooting A western costume party with special activities and Complex. Three days of shooting competitions, treats for our younger members. including trap, skeet, sporting clays and silhouette shooting events. NOVEMBER One of One Thousand Societv Members Shootout events. Public program: Seasons of the Buffalo.2 pm. Historical Center Coe Auditorium. 19th Annual Plains Indian Seminar: Art of the Plains - Voices of the Present. Public program: Seasons of the Buffalo.2 pm. Historical Center Coe Auditorium. Public program'. Seasons of the Buffalo.2 pm. Historical I€I{5 is putrlished quiutsly # a ben€{it of membershlp in lhe Bufialo Eiil lfistorical Crnter Fu informatron Center Coe Auditorium. about mmberghip contact Jme Sanderu, Director o{ Membership, Bulfalo Bill'l{istorical Centet 7?0 Shdidan Avenuo, Cody, IAI{ 82414 o1 catl (30fl 58Va77l' *t 255 Buffalo Bill Historical Center closes for the season. Requst Bsmjssion to cqpy, xepdni or disftibuie dticles in ary ftedium ox fomat.