Journal of Studies in Language, Culture and Society (JSLCS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEMA Regular Lecture Series, 2011-2012

Volume 2 November 2012 CEMA Centre d’Études Maghrébines en Algérie Newsletter Letter from the Director, Dr. CEMA Special Lecture Series: CEMA Activities at a Glance Robert P. Parks, and Letter The Saharan Lectures & The Pages 5-9 from Associate Director, Dr. CEMA Public Health Lecture Karim Ouaras Series Outreach, AIMS 2013 CFP, Page 2-3 Page 4 Scholars, Recent Publications Pages 10-14 ; Volume Volume 22 2 NovemberNovember 20122012 Letter from CEMA Director, Dr. Robert P. Parks 2011-2012 has been an exciting year at CEMA. Between November 2011 and October 2012, more than 90 researchers spoke at CEMA activities – at fifteen lectures, two thematic round-table activities, two symposia, one six-week fellowship, and one three-day conference. CEMA assisted the research of 47 American and international scholars. And we received nearly 6,500 walk-in visits to the center. Activity is booming and as CEMA grows, so does its audience. We hope to be able to expand our activities to Algiers and the universities and research institutes of the Center of the country this year. Programmatically, we have been active. This year CEMA organized twelve lectures as part of its regular lecture series, which primarily highlights new or on-going research in history, politics, and sociology. CEMA also organizes three special lecture series: ‘the Oran Lecture,’ ‘the Saharan Lectures,’ and a new series on Public Health. ‘The Oran Lecture,’ which we hope to recommence this year, highlights the research of non-Orani Maghrebi scholars in the social sciences and the humanities. Co- organized with the National Research Center for Social and Cultural Anthropology (CRASC), ‘The Saharan Lectures’ builds from the AIMS-West African Research Association (WARA) Saharan Crossroads Initiative, which seeks to underscore the cultural, economic, and social links between the Maghreb and Sahel region. -

The Journal of Studies in Language, Culture and Society (JSLCS)

Volume 1/N°1 December, 2018 The Journal of Studies in Language, Culture and Society (JSLCS) Editor in chief: Dr. Nadia Idri UNIVERSITÉ ABDERRAHMANE MIRA BEJAIA FACULTÉ DES LETTRES ET DES LANGUES www.univ-bejaia/JSLCS ISSN : 1750-2676 © All rights reserved Journal of Studies in Language, Culture and Society (JSLCS) is an academic multidisciplinary open access and peer-reviewed journal that publishes original research that turns around phenomena related to language, culture and society. JSLCS welcomes papers that reflect sound methodologies, updated theoretical analyses and original empirical and practical findings related to various disciplines like linguistics and languages, civilisation and literature, sociology, psychology, translation, anthropology, education, pedagogy, ICT, communication, cultural/inter-cultural studies, philosophy, history, religion, and the like. Editor in Chief Dr Nadia Idri, Faculty of Arts and Languages, University of Bejaia, Algeria Editorial Board Abdelhak Elaggoune, University 8 Mai 1945, Guelma, Algeria Ahmed Chaouki Hoadjli, University of Biskra, Algeria Amar Guendouzi, University Mouloud Mammeri, Tizi Ouzou, Algeria Amine Belmekki, University of tlemcen, Algeria Anita Welch, Institute of Education, USA Christian Ludwig, Essen/NRW, Germany Christophe Ippolito Chris, School of Modern Languages at Georgia Tech’s Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, USA Farouk Bouhadiba, University of Oran, Algeria Fodil Sadek, University Mouloud Mammeri, Tizi Ouzou, Algeria Fouad Mami, University of Adrar, Algeria Ghania Ouahmiche, University of Oran, Algeria Hacène Hamada, Ens Constantine, Algeria Hanane Sarnou, University of Mostaganem, Algeria Judit Papp, Hungarian Language and Literature, University of Naples "L'Orientale" Leyla Bellour, Mila University Center, Algeria Limame Barbouchi, Faculty of Chariaa in Smara, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco Manisha Anand Patil, Head, Yashavantrao Chavan Institute of Science, India Mimouna Zitouni, University of Mohamed Ben Ahmed, Oran 2, Algeria Mohammad H. -

Second General Meeting

Tuning Middle East and North Africa T-MEDA Second General Meeting MINUTES Bilbao, 28 September - 02 October 2014 Second General Meeting Bilbao, 28 September - 02 October 2014 Second General Meeting Participants N Given Name Family Name University 1 Somaya Abou Abdou Suez Canal University 2 Hashem Abu Snieneh Palestine Ahliyeh University College / Bethlehem Abu-Orabi 3 Sultan Association of Arab Universities Aladwan Ahmad Abidrabbu 4 Alhusban Hashemite University Al-Sa'ed Ahmed 5 Ahmed Suez Canal University Mohamed Amin 6 Tamer Al Hajeh Arab International University 7 Nijmeh AL-Atiyyat Hashemite University 8 Mutasim Alqudah Hashemite University 9 Sami Basha Palestine Ahliyeh University College / Bethlehem 10 Mohammad Bashayreh Yarmouk University 11 Monther Bataineh Association of Arab Universities 12 Pablo Beneitone University of Deusto 13 Gerold Beyer University of Angers 14 Jenneke Bosch-Boesjes University of Groningen 15 Abderrahime Bouali University Mohammed First 16 Rashad Brydan University of Omar Almukhtar 17 Karem Dassi University of Tunis 18 Alvaro de la Rica University of Deusto 19 Ivan Dyukarev University of Deusto 20 Hamid El Debs University of Balamand 21 Ahmad El Zein Modern University for Business and Science 22 Hesham Elarnaouty Beirut Arab Universtity 23 Islam Elgammal Suez Canal University 24 Hana El-Ghali Directorate General Of Higher Education 25 Abeer Saad Eswi Cairo University 26 Andrea Gattini University of Padova 27 Ana Goytia Prat University of Deusto International University for Science and 28 Rafee Hakky Technology -

Inside Leaflet

www inside-project org Including Students with Impairments in Distance Education Project No: 598763-EPP-1-2018-1-EL-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP (Including Students with Impairments in InSIDE:Distance Education) is a Capacity Building in Higher Education (Erasmus+) project that aims at developing accessible, inclusive and educationally effective Distance Education (DE) programmes for individuals with Visual, Hearing and Mobility (ViHeMo) impairments through a user-centred design DE programmes will be structured on 3 axes: a) educational material, b) DE delivery system, and c) educational effectiveness / pedagogical approaches Eleven universities from Maghreb – 4 from Morocco, 4 from Algeria and 3 from Tunisia – will be trained by University of Macedonia (leading institution - Greece), National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (Greece) and Johannes Kepler University (Austria), and will implement the DE programmes at hand These programmes will deliver key competences for vocational rehabilitation, and will provide opportunities for lifelong learning, skills enhancement, and personal fulfillment with the ultimate aim of suggesting an intelligent solution against the problems of limited access or high percentage of dropouts of individuals with impairments in Higher Education Overall objectives Develop and pilot new and innovative, accessible, and inclusive DE programmes aiming to improve the quality in Higher Education for individuals with ViHeMo impairments and offering flexible learning and virtual mobility Reform the operation of Accessibility Units -

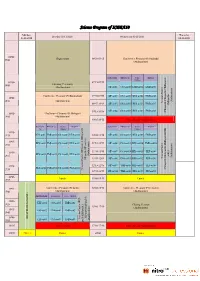

Science Program of ICEEA10

Science Program of ICEEA10 Monday Thursday Tuesday 02-11-2010 Wednesday 03-11-2010 01-11-2010 04-11-2010 08h00- Registration 08h30-09h15 Conference Pleanary (Pr Ouahabi) 09h00 (Auditaurium) Auditaurium Bibliothéque Centre Amph22 - Culturel h h h 09 00- 09 15-09 35 po01 - 10h00 Opening Ceremony (Auditaurium) SIP-or01 CSA-or08 EMD-or04 EMD-or05 po012 TMS po012 Conference Pleanary (Pr Boumahrat) 09h35-09h55 SIP-or02 CSA-or09 RES-or06 EMD-or06 - h 10 00- po06 - PES h - 10 35 (Auditaurium) (Auditaurium) h h Poster Session 09 55-10 15 SIP-or03 CSA-or010 RES-or07 EMD-or07 TMS po01 - h h SIP-or04 CSA-or011 RES-or08 EMD-or08 10 15-10 35 (PEA 10h35- Conference Pleanary (Pr Matagne) 11h10 (Auditaurium) 10h35-10h55 Cofee Breack (Auditaurium) Auditauriu Bibliothéque Centre Amph22 Auditaurium Bibliothéque Centre Amph22 m Culturel Culturel - h 11 15- EMD - po023 11h35 RES-or01 TMS-or01 CSA-or01 PEA-or 01 - 10h55-11h15 SIP-or05 CSA-or012 RES-or09 EMD-or09 po01 - RES h - 11 35- 11h15-11h35 h RES-or02 TMS-or02 CSA-or02 PEA-or02 SIP-or06 CSA-or013 RES-or010 EMD-or010 po016), 11 55 - po012 - SIP - h h 11 35-11 55 SIP-or07 CSA-or014 RES-or011 EEF-or04 EMD po018, 11h55- - RES-or03 TMS-or03 CSA-or03 PEA-or03 po01 (Auditaurium) h - 12 15 po022 (Auditaurium) CSA Session Poster Session h h - SIP 11 55-12 15 SIP-or08 CSA-or015 RES-or012 EEF-or05 po01 h h - 12h20- 12 15-12 35 SIP-or09 TMS-or05 RES-or013 EEF-or06 RES-or04 TMS-or04 CSA-or04 PEA-or04 Session Poster (RES Poster Session 12h35 (CSA 12h35-12h55 SIP-or010 TMS-or06 RES-or05 PEA-or05 12h45- Lunch 13h00-14h30 -

« Ecosystems, Biodiversity and Eco-Development »

University of Sciences & Technology Houari Boumediene, Algiers- Algeria Faculty of Biological Sciences Laboratory of Dynamic & Biodiversity « Ecosystems, Biodiversity and Eco-development » 03-05 NOVEMBER, 2017 - TAMANRASSET - ALGERIA Publisher : Publications Direction. Chlef University (Algeria) ii COPYRIGHT NOTICE Copyright © 2020 by the Laboratory of Dynamic & Biodiversity (USTHB, Algiers, Algeria). Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than Laboratory of Dynamic & Biodiversity must be honored. Patrons University of Sciences and Technologies Faculty of Biological Sciences Houari Boumedienne of Algiers, Algeria Sponsors Supporting Publisher Edition Hassiba Benbouali University of Chlef (Algeria) “Revue Nature et Technologie” NATEC iii COMMITTEES Organizing committee: ❖ President: Pr. Abdeslem ARAB (Houari Boumedienne University of Sciences and Tehnology USTHB, Algiers ❖ Honorary president: Pr. Mohamed SAIDI (Rector of USTHB) Advisors: ❖ Badis BAKOUCHE (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Amine CHAFAI (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Amina BELAIFA BOUAMRA (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Ilham Yasmine ARAB (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Ahlem RAYANE (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Ghiles SMAOUNE (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Hanane BOUMERDASSI (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) Scientific advisory committee ❖ Pr. ABI AYAD S.M.A. (Univ. Oran- Algeria) ❖ Pr. ABI SAID M. (Univ. Beirut- Lebanon) ❖ Pr. ADIB S. (Univ. Lattakia- Syria) ❖ Pr. CHAKALI G. (ENSSA, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Pr. CHOUIKHI A. (INOC, Izmir- Turkey) ❖ Pr. HACENE H. (USTHB, Algiers- Algeria) ❖ Pr. HEDAYATI S.A. (Univ. Gorgan- Iran) ❖ Pr. KARA M.H. (Univ. Annaba- Algeria) ❖ Pr. -

General Introduction

Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Es-Senia- Oran Faculty of Letters, Languages and Arts Department of Anglo-Saxon Languages English Section Magister Dissertation in Sociolinguistics Language Contact and Language Management in Algeria A Sociolinguistic Study of Language Policy in Algeria Submitted by: Miss. Sarra GHOUL Members of the Jury: President: MOULFI Leila MCA- University of Oran Supervisor: BENHATTAB Abdelkader Lotfi MCA- University of Oran Examiner: LAKHDAR BARKA Ferida MCA- University of Oran Examiner: ABDELHAY Bakhta MCA- University of Mostaganem 2012-2013 DEDICATION To my beloved mother, This dissertation is lovingly dedicated to you mama Your support, encouragement, and constant love have sustained me throughout my life. ―Mom you are the sun that brightens my life‖. I am at this stage and all the merit returns to you mom. I love you … THANK YOU for everything. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It gives me great pleasure to express my gratitude to all those people who supported me and contributed in making this thesis possible. First and above all, I praise ALLAH, the Almighty for blessing, protecting, and guiding me to proceed successfully. I could never have accomplished this work without the faith I have in the Almighty. This thesis appears in its current form due to the assistance and guidance of several people. I would therefore like to offer my sincere thanks to all of them. Dr. Benhattab Abdelkader Lotfi, my esteemed supervisor, my cordial thanks for accepting me as a magister student, your encouragement, thoughtful guidance, and patience. Dr. Boukereris Louafia, I greatly appreciate your excellent assistance and guidance. -

Derecho ENGL Tuning MEDA Color.Indd 1 16/2/17 08:32:02

DDerechoerecho ENGLENGL TuningTuning MEDAMEDA color.inddcolor.indd 1 116/2/176/2/17 008:32:028:32:02 DDerechoerecho ENGLENGL TuningTuning MEDAMEDA color.inddcolor.indd 2 116/2/176/2/17 008:32:038:32:03 Reference Points for the Design and Delivery of Degree Programmes in Law DDerechoerecho ENGLENGL TuningTuning MEDAMEDA color.inddcolor.indd 3 116/2/176/2/17 008:32:038:32:03 DDerechoerecho ENGLENGL TuningTuning MEDAMEDA color.inddcolor.indd 4 116/2/176/2/17 008:32:038:32:03 Tuning Middle East and North Africa Reference Points for the Design and Delivery of Degree Programmes in Law Mohammad Hussein Bashayreh (editor) Authors: Mohammad Hussein Bashayreh, Darina Saliba Abi Chedid, Abdullah Abdulkarim Abdullah, Maher Kabakibi, Noureddine Kridis, Sana Totah, Mutasim Alqudah, Houria Yessad, Yahya Haloui, Madjid Kaci, Esam F. Husain Alhain, Ahmed Weshahi, Basem S. M. Boshnaq, Mohamed Benjelloun, Anas Lamchichi, Khaled Chiat, Mohamed Rafat Mahmoud, Jenneke Bosh-Boesjes, Maria Luisa Sanchez Barrueco, Andrea Gattini, Andrey Kuvshunov 2016 University of Deusto Bilbao DDerechoerecho ENGLENGL TuningTuning MEDAMEDA color.inddcolor.indd 5 116/2/176/2/17 008:32:038:32:03 Reference Points for the Design and Delivery of Degree Pro- grammes in Law Reference Points are non-prescriptive indicators and general rec- ommendations that aim to support the design, delivery and articu- lation of degree programmes in Law. Subject area group including experts from Middle East, North Africa and Europe has developed this document in consultation with different stakeholders (aca- demics, employers, students and graduates). This publication has been prepared within Tuning Middle East and North Africa project 543948-TEMPUS-1-2013-1-ES-TEMPUS-JPCR. -

Procceding ICEECA 2014

The Second International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Control Applications ICEECA’1 4 Constantine 18 -20 November, Algeria The Second International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Control Applications ICEECA’2014 Organized by Faculty of Sciences and Technology, University Constantine 1 Technically Sponsored by Springer IEEE Computational Intelligence Society Czech&Slovak Chapter CSC Chapter IEEE France Section CSC Chapter IEEE Norway Section ITA4Innovations Centrum excelence MIR Labs Innovation First 1 The Second International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Control Applications ICEECA’1 4 Constantine 18 -20 November, Algeria General Chairs Salim Filali University Constantine1, Algeria Mohammed Chadli University of Picardie Jules Verne Amiens, France Steering Committee Sofiane Bououden University of Khenchela, Algeria Mohammed Chadli University of Picardie Jules Verne Amiens, France Hamid reza Karimi University of Agder, Norway Peng Shi Victoria University, Australia Program Chairs Sofiane Bououden University of Khenchela, Algeria Ivan Zelinka Technical University of Ostrava, Czech Republic International Advisory Committee Khaled Belarbi University Constantine1, Algeria Vincent Wertz Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgique Peng Shi Victoria University, Australia Abedlhamid Tayebi Lakehead University, Canada Hamid Reza Karimi University of Agder, Norway L.X. Zhang Zhejiang University, China Abdelfatah Charef University Constantine1, Algeria Pierre Borne Ecole Centrale de Lille, France N. B. Braiek L'Ecole -

498004 1 En Bookfrontmatter 1..15

Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems Volume 156 Series Editor Janusz Kacprzyk, Systems Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Advisory Editors Fernando Gomide, Department of Computer Engineering and Automation—DCA, School of Electrical and Computer Engineering—FEEC, University of Campinas— UNICAMP, São Paulo, Brazil Okyay Kaynak, Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Bogazici University, Istanbul, Turkey Derong Liu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, USA; Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Witold Pedrycz, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Alberta, Alberta, Canada; Systems Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Marios M. Polycarpou, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, KIOS Research Center for Intelligent Systems and Networks, University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus Imre J. Rudas, Óbuda University, Budapest, Hungary Jun Wang, Department of Computer Science, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong The series “Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems” publishes the latest developments in Networks and Systems—quickly, informally and with high quality. Original research reported in proceedings and post-proceedings represents the core of LNNS. Volumes published in LNNS embrace all aspects and subfields of, as well as new challenges in, Networks and Systems. The series contains proceedings and edited volumes in systems and networks, spanning -

Transports, Logistics and Multi Modality

UNIMED Mediterranean Universities Union The European experience in logistic education and possible actions to satisfy the needs of the Mediterranean partner countries (MPC) LECCE RAILMED 11-12 OCTOBER 2012 MARCELLO SCALISI UNIMED Executive Director UNIMED Foundation 1991: Foundation with 24 associated Universities of the Mediterranean basin Today: Network of 79 Universities from 21 countries of the two shores of the Mediterranean UNIMED Member States Associated Universities ALBANIA University of Tirana – Tirana – American University of Tirana ALGERIA University of Algiers; EPAU - Ecole Polytechnique d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme – Algiers; University “Badji Mokhtar” – Annaba; University of Béjaia; University of Blida; University of Constantine; University of Mostaganem; University “Es Senia” – Oran; ENSET - Ecole Nationale Supérieure de l’EnseignementTechnique – Oran; University of Tizi Ouzou; University “Abou Bekr Belkeid” - Tlemcen CYPRUS Cyprus University of Technology – Lemesos; University of Cyprus - Nicosia EGYPT University of Alexandria; Arab Academy for Science and Technology and Maritime Transport – Alexandria; University of Cairo FINLANDIA University of Tampere FRANCE University of Paris 8 JORDAN University“Al al-Bayt” – Amman; University of Jordan – Amman; Hashemite University - Zarqa GREECE University of Athens; University of Panteion - Athens ISRAEL Hebrew University – Jerusalem; University Ben Gurion – Negev; University of Tel Aviv Associated Universities ITALY Università di Bari; Università di Bologna; Università oi Cagliari; -

The Media Consumption Patterns of the Arab Spring Revolutions

The Media Consumption Patterns of the Arab Spring revolutions A Field Study for the students' Perceptions in the faculty of Journalism and Press at Alyarmouk University By prof. Tahseen Mohammad Anis Sharadga Assisstant Professor Al-Zarqa'a University Faculty of Journalism Jordan 2015 1 1 Abstract The study aimed to identify the media consumption patterns of the Arab Spring revolutions from the viewpoint of Yarmouk University students. In addition to detect whether there is a statistically significant differences at the level of significance (α = 0.05) with respect to the views of respondents regarding employing the study dimensions related to political, military and human dimension due to the variables of the study (sex, educational qualification). The study sample consisted of Yarmouk University students (200) students. The descriptive analytical method was used, through which the following results were concluded: 1. Identifying the media consumption patterns on the Arab Spring. 2. No statistically significant differences at the level of significance (α = 0.05) with respect to the views of respondents about media consumption patterns of the Arab Spring due to the variable of sex. 3. There are no statistically significant differences at the level of significance (α = 0.05) with respect to the views of respondents about media consumption patterns around of Arab Spring due to the educational qualification variable. Based on the results of the theoretical and empirical study, the researcher suggests the following: Identify the mechanisms through which media networks broadcast the political propaganda related to the political, military and human dimensions, and the procedures used to do so. Also studying the methods by which the propaganda messages are being broadcast and analyzed, and employing them for the public interest.