Life in a Carousel Is What Most Impressed Colin Bent Phillip in 1905, and It Is This Same Simplicity That Continues to Make His Work So Impressive and Enduring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Pickles (Presidenl 1976-1978) the FELL and ROCK JOURNAL

Charles Pickles (Presidenl 1976-1978) THE FELL AND ROCK JOURNAL Edited by TERRY SULLIVAN No. 66 VOLUME XXIII (No. I) Published by THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT 1978 CONTENTS PAGE Cat Among the Pigeons ... ... ... Ivan Waller 1 The Attempt on Latok II ... ... ... Pal Fearneough 1 The Engadine Marathon ... ... ... Gordon Dyke 12 Woubits - A Case History ... ... ... Ian Roper 19 More Shambles in the Alps Bob Allen 23 Annual Dinner Meet, 1976 Bill Comstive 28 Annual Dinner Meet, 1977 ... ... Maureen Linton 29 The London Section ... ... ... Margaret Darvall 31 High Level Walking in the Pennine Alps John Waddams 32 New Climbs and Notes ... ... ... Ed Grindley 44 In Memoriam... ... ... ... ... ... ... 60 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 76 Reviews ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 82 Officers of the Club 117 Meets 119 © FELL AND ROCK CLIMBINO CLUB PRINTED BY HILL & TYLER LTD., NOTTINGHAM Editor T. SULLIVAN B BLOCK UNIVERSITY PARK NOTTINGHAM Librarian IReviews MRS. J. FARRINGTON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BAILRIGG LANCASTER New Climbs D. MILLER 31 BOSBURN DRIVE MELLOR BROOK BLACKBURN LANCASHIRE Obituary Notices R. BROTHERTON SILVER BIRCH FELL LANE PENRITH CUMBRIA Exchange Journals Please send these to the Librarian GAT AMONG THE PIGEONS Ivan Waller Memory is a strange thing. I once re-visited the Dolomites where I had climbed as a young man and thought I could remember in fair detail everywhere I had been. To my surprise I found all that remained in my mind were a few of the spect• acular peaks, and huge areas in between, I might never have seen before. I have no doubt my memory of events behaves in just the same way, and imagination tries to fill the gaps. -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

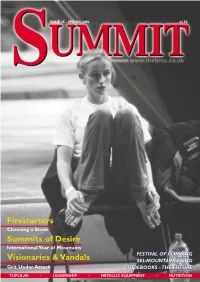

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest. -

Alpine Club Notes

Alpine Club Notes OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 2001 PRESIDENT. .. D KScottCBE VICE PRESIDENTS .. PF Fagan BMWragg HONORARY SECRETARy . GD Hughes HONORARY TREASURER AL Robinson HONORARY LIBRARIAN DJ Lovatt HONORARY EDITOR OF THE ALPINE JOURNAL E Douglas HONORARY GUIDEBOOKS COMMISSIONING EDITOR . LN Griffin COMMITTEE ELECTIVE MEMBERS . E RAllen JC Evans W ACNewson W JE Norton CJ Radcliffe RM Scott RL Stephens R Turnbull PWickens OFFICE BEARERS LIBRARIAN EMERITUS . RLawford HONORARY ARCHIVIST . PT Berg HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S PICTURES P Mallalieu HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S ARTEFACTS .. RLawford HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S MONUMENTS. D JLovatt CHAIRMAN OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE .... RFMorgan CHAIRMAN OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE MH Johnston CHAIRMAN OF THE LIBRARY COUNCIL ..... GC Band CHAIRMAN OF THE MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE RM Scott CHAIRMAN OF THE GUIDEBOOKS EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION BOARD LN Griffin GUIDEBOOKS PRODUCTION MANAGER JN Slee-Smith ASSISTANT EDITORS OF THE Alpine Journal .. JL Bermudez GW Templeman PRODUCTION EDITOR OF THE Alpine Journal Mrs JMerz 347 348 THE ALPINE JOURNAL 2001 ASSISTANT HONORARY SECRETARIES: ANNUAL WINTER DINNER MH Johnston LECTURES . MWHDay MEETS.. .. JC Evans MEMBERSHIP . RM Scott TRUSTEES . MFBaker JG RHarding S N Beare HONORARY SOLICITOR . PG C Sanders AUDITORS .. Pannell Kerr Forster ASSISTANT SECRETARY (ADMINISTRATION) .. Sheila Harrison ALPINE CLIMBING GROUP PRESIDENT. D Wilkinson HONORARY SECRETARY RARuddle GENERAL, INFORMAL, AND CLIMBING MEETINGS 2000 11 January General Meeting: Mick Fowler and Steve -

Alpine Club Notes

Alpine Club Notes OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1997 PRESIDENT . Sir Christian Bonington CBE VICE PRESIDENTS . J GRHarding LN Griffin HONORARY SECRETARy . DJ Lovatt HONORARY TREASURER . AL Robinson HONORARY LIBRARIAN .. DJ Lovatt HONORARY EDITOR . Mrs J Merz COMMITTEE ELECTIVE MEMBERS E Douglas Col MH Kefford PJ Knott WH O'Connor K Phillips DD Clark-Lowes BJ Murphy WJ Powell DW Walker EXTRA COMMITTEE MEMBERS M JEsten GC Holden OFFICE BEARERS LIBRARIAN EMERITUS '" . R Lawford HONORARY ARCHIVIST . Miss L Gollancz HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S PICTURES P Mallalieu HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S ARTEFACTS .. R Lawford CHAIRMAN OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE RFMorgan CHAIRMAN OF THE GUIDEBOOKS EDITORIAL & PRODUCTION BOARD .. LN Griffin CHAIRMAN OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE .. MH Johnston CHAIRMAN OF THE LIBRARY COUNCIL . GC Band CHAIRMAN OF THE MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE MWFletcher ASSISTANT EDITORS OF THE Alpine Journal .. JL Bermudez GW Templeman 364 ALPINE CLUB NOTES 365 ASSISTANT HONORARY SECRETARIES: ANNUAL WINTER DINNER MH Johnston BMC LIAISON . P Wickens LECTURES. E Douglas MEETS . PJ Knott MEMBERSHIP . MW Fletcher TRUSTEES ... MF Baker JGR Harding S N Beare HONORARY SOLICITOR .. PG C Sanders AUDITORS AM Dowler Russell New ALPINE CLIMBING GROUP PRESIDENT D Wilkinson HONORARY SECRETARy .. RA Ruddle AC GENERAL AND INFORMAL MEETINGS 1996 16 January General Meeting: Mick Fowler, The North-East Pillar of Taweche 23 January Val d'Aosta evening: Mont Blanc 30 January Informal Meeting: Mike Binnie, Two Years in the Hindu Kush 13 February General Meeting: David Hamilton, -

3Rd Press Release Chamonix, 12 March the 17 Piolets D’Or : the 6 Nominees from 22Nd to 25Th April 2009 Chamonix-Mont-Blanc – Courmayeur

3rd Press Release Chamonix, 12 March The 17 Piolets d’Or : the 6 nominees From 22nd to 25th April 2009 Chamonix-Mont-Blanc – Courmayeur The International jury of the 17th Piolets d’Or have chosen the six ascents to be nominated from among the 57 first ascents and linked routes achieved in mountains throughout the world during the course of 2008. Most of the protagonists of these six notable achievements will be present in Chamonix and Courmayeur from 22nd to 25th April. With them will be climbers from all over the world: they will be gathering to celebrate their great passion in a real festival atmosphere. Presentations, debates, films, meetings and other cultural activities will be shared between Courmayeur and Chamonix-Mont-Blanc, from 22nd to 25th April. For all information: www.pioletdor.org. 1) THE NOMINEES FOR THE 17TH PIOLETS D’OR THE ASCENTS First ascent of the South-West face of Kamet (7756m, India). A mixed Japanese team composed of Kazuya Hiraide and Kei Taniguchi opened up the unclimbed South-west face of Kamet in alpine style, between 26th September and 7th October 2008. Name of Route : Samurai Direct. Height of Climb: 1800m. Difficulties declared: mixed M5+, ice 5+. New Route on the South face of Nuptse I (7861m, Nepal). Frenchmen Stéphane Benoist and Patrice Glairon Rappaz achieved a route on the south face of Nuptse I in alpine style between the 27 and 30 October 2008. Name of Route: Are you experienced ? Height of climb: 2000m. Difficulties declared: mixed M5, ice 90°. First complete ascent of the East face of Cerro Escudo (2450m, Chili). -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B. -

Journal of Alpine Research | Revue De Géographie Alpine

Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine 101-1 | 2013 Lever le voile : les montagnes au masculin-féminin Gender relations in French and British mountaineering The lens of autobiographies of female mountaineers, from d’Angeville (1794-1871) to Destivelle (1960- ) Delphine Moraldo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rga/2027 DOI: 10.4000/rga.2027 ISSN: 1760-7426 Publisher Association pour la diffusion de la recherche alpine Electronic reference Delphine Moraldo, « Gender relations in French and British mountaineering », Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine [Online], 101-1 | 2013, Online since 03 September 2013, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rga/2027 ; DOI : 10.4000/rga.2027 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. La Revue de Géographie Alpine est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Gender relations in French and British mountaineering 1 Gender relations in French and British mountaineering The lens of autobiographies of female mountaineers, from d’Angeville (1794-1871) to Destivelle (1960- ) Delphine Moraldo EDITOR'S NOTE Translation: Delphine Moraldo 1 Since alpine clubs first appeared in Europe in the mid 19th century, mountaineering has been one of the most strongly masculinised practices. Not only are mountaineers mostly men, but mountaineering involves manly and heroic social dispositions that establish male domination (Louveau, 2009). 2 Because mountain activities are a feminine-masculine construction, I chose here to look at the practice of mountaineering through the lens of autobiographies of female mountaineers. In these accounts, women never fail to mention male mountaineers, thus giving us an insight into men’s perception of them. -

Alpine Club Notes

Alpine Club Notes OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1999 PRESIDENT .. DK Scott CBE VICE PRESIDENTS DrM J Esten P Braithwaite HONORARY SECRETARY.. .. .. GD Hughes HONORARY TREASURER .. .. AL Robinson HONORARY LIBRARIAN .. DJ Lovatt HONORARY EDITOR OF THE ALPINE JOURNAL E Douglas HONORARY GUIDEBOOKS COMMISSIONING EDITOR .. LN Griffin COMMITTEE ELECTIVE MEMBERS .. DD Clark-Lowes JFC Fotheringham JMO'B Gore WJ Powell A Vila DWWalker E RAllen GCHolden B MWragg OFFICE BEARERS LIBRARIAN EMERITUS . RLawford HONORARY ARCHIVIST .. Miss L Gollancz HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S PICTURES. P Mallalieu HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S ARTEFACTS .. RLawfo;rd HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S MONUMENTS. DJ Lovatt CHAIRMAN OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE .. RFMorgan CHAIRMAN OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE . MH Johnston CHAIRMAN OF THE LIBRARY COUNCIL GC Band CHAIRMAN OF THE MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE MWFletcher ASSISTANT EDITORS OF THE Alpine Journal .. JL Bermudez GW Templeman PRODUCTION EDITOR OF THE Alpine Journal Mrs J Merz 347 348 THE ALPINE J OURN AL 1999 AsSISTANT HONORARY SECRETARIES: ANNuAL WINTER DINNER .. MH Johnston BMC LIAISON .. .. GCHolden LECTURES . D 0 Wynne-Jones NORTHERN LECTURE .. E Douglas MEETS . A Vila MEMBERSHIP .. MW Fletcher TRUSTEES . MFBaker JG RHarding S NBeare HONORARY SOLICITOR . PG C Sanders AUDITORS HRLloyd Pannell Kerr Forster ALPINE CLIMBING GROUP PRESIDENT. D Wilkinson HONORARY SECRETARY RA Ruddle GENERAL, INFORMAL, AND CLIMBING MEETINGS 1998 13 January General Meeting: David Hamilton, Pakistan 27 January Informal Meeting: Roger Smith Arolla Alps 10 February -

MONTAGNERE PASSY 9 -10 -11 AOUT 2013 23Ème SALON INTERNATIONAL DU LIVRE DE MONTAGNE Imp

Pascal Tournaire AR CHI TEC TU en MONTAGNERE PASSY 9 -10 -11 AOUT 2013 23ème SALON rnaire INTERNATIONAL DU LIVRE DE MONTAGNE Imp. PLANCHER - Tél. 04 50 97 46 00 Crédit photo : Pascal Tou salonLivrePassyVz.indd 1 En partenariat avec LE JARDIN DES CIMES 09/04/13 07:43 HAUTE-SAVOIE-FRANCE - Tél. / Fax 04 50 58 81 73 - www.salon-livre-montagne.com - [email protected] 1 TRANSACTIONS - LOCATIONS SYNDIC D’IMMEUBLES les contamines immobilier Jean-Marc PEILLEX, MAÎTRE EN DROIT Cl 639 route de Notre Dame de la Gorge 74170 LES CONTAMINES-MONTJOIE Tél. 04 50 47 01 82 - Fax 04 50 47 08 54 [email protected] Retrouvez notre rubrique Librairie-Cartothèque en ligne sur notre site www.auvieuxcampeur.fr Un large choix de guides, topos et cartes ainsi qu’une sélection de livres vous y attendent ! SALLANCHES - 925 route du Fayet - 74700 - Tél. : 04 50 91 26 62 Et aussi à : Lyon - Thonon-Les-Bains - Sallanches - Toulouse-labège - Strasbourg - Albertville - Marseille - Grenoble - Chambéry (Eté 2013) Montagne de Livres… …Livres de Montagne 23ème Salon International du Livre de Montagne de Passy 9 - 10 - 11 août 2013 "ARCHITECTURE EN MONTAGNE" Président d’Honneur Jean-François LYON-CAEN Architecte, Maître-assistant, Responsable du Master et de l’Equipe de recherche « architecture-paysage-montagne » à l’Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Grenoble Achetez votre entrée au Salon du Livre de Montagne directement à l’Offi ce du Tourisme de Passy Contactez le 04 50 58 80 52 Téléphone du salon pour les 3 jours : 06 86 76 69 04 Siège