Landscape Without Nature: Ecological Reflections in Contemporary Chinese Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian

Macalester International Volume 18 Chinese Worlds: Multiple Temporalities Article 12 and Transformations Spring 2007 Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian Desheng Fang Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Qian, Zhuzhong and Fang, Desheng (2007) "Towards Chinese Calligraphy," Macalester International: Vol. 18, Article 12. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Chinese Calligraphy Qian Zhuzhong and Fang Desheng I. History of Chinese Calligraphy: A Brief Overview Chinese calligraphy, like script itself, began with hieroglyphs and, over time, has developed various styles and schools, constituting an important part of the national cultural heritage. Chinese scripts are generally divided into five categories: Seal script, Clerical (or Official) script, Regular script, Running script, and Cursive script. What follows is a brief introduction of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy. A. From Prehistory to Xia Dynasty (ca. 16 century B.C.) The art of calligraphy began with the creation of Chinese characters. Without modern technology in ancient times, “Sound couldn’t travel to another place and couldn’t remain, so writings came into being to act as the track of meaning and sound.”1 However, instead of characters, the first calligraphy works were picture-like symbols. These symbols first appeared on ceramic vessels and only showed ambiguous con- cepts without clear meanings. -

Cultured New Yorkers Explore the Culture and History of Suzhou

Cultured New Yorkers Explore the Culture and History of Suzhou-style Classical Gardens at Opening Ceremony for “Breaking Ground: Twenty Years of the New York Chinese Scholar’s Garden” at Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden in Staten Island The exhibition, sponsored in part by the Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Culture, Radio, Television and Tourism Administration, celebrates the exquisite beauty of Suzhou’s classical gardens through December 29, 2019 NEW YORK, NY – OCTOBER 28, 2019 – The Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Culture, Radio, Television and Tourism Administration (Suzhou Tourism) showcased Suzhou’s rich culture to attendees at the opening ceremony of the visual art exhibition “Breaking Ground: Twenty Years of the New York Chinese Scholar’s Garden,” on Saturday, October 19 at Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden in Staten Island, New York City. As a sponsor of the exhibition, Suzhou Tourism branding will be present throughout its run which concludes on December 29, 2019. “Breaking Ground” explores the cultural impact of the New York Chinese Scholar’s Garden (NYCSG), the first authentic classical scholar’s garden erected in the United States. All of the NYCSG’s architectural components were fabricated in Suzhou including roof and floor tiles, columns and beams, doors and windows, bridges and paving materials, and experts from Suzhou were on- site in Staten Island to oversee the garden’s construction in 1999. “Breaking Ground” brings the fascinating story of this unique space to life through artifacts, photographs, and artwork, featuring work from Robert Bunkin, Michael Falco, Annemarie Trombetta, and Andrea Phillips. Modeled after traditional Ming Dynasty gardens (1368-1644), the garden features a bamboo forest path, waterfalls, a Koi-filled pond, Chinese calligraphy, and a variety of Ghongshi scholar’s rocks. -

Art of the Mountain

Wang Wusheng, Disciples of Buddha and Fairy Maiden Peak, taken at Peak Lying on the Clouds June 2004, 8 A.M. ART OF THE MOUNTAIN THROUGH THE CHINESE PHOTOGRAPHER’S LENS Organized by China Institute Gallery Curated by Willow Weilan Hai, Jerome Silbergeld, and Rong Jiang A traveling exhibition available through summer 2023 ART OF THE MOUNTAIN: THROUGH THE CHINESE PHOTOGRAPHER’S LENS Organized by China Institute Gallery Curated by Willow Weilan Hai, Jerome Silbergeld, and Rong Jiang A traveling exhibition available through summer 2023 In Chinese legend, mountains are the pillars that hold up the sky. Mountains were seen as places that nurture life. Their veneration took the form of rituals, retreat from social society, and aesthetic appreciation with a defining role in Chinese art and culture. Art of the Mountain will consist of three sections: Revered Mountains of China will introduce the geography, history, legends, and culture that are associated with Chinese mountains and will include photographs by Hou Heliang, Kang Songbai and Kang Liang, Li Daguang, Lin Maozhao, Li Xueliang, Lu Hao, Zhang Anlu, Xiao Chao, Yan Shi, Wang Jing, Zhang Jiaxuan, Zhang Huajie, and Zheng Congli. Landscape Aesthetics in Photography will present Wang Wusheng’s photography of Mount Huangshan, also known as Yellow Mountain, to reflect the renowned Chinese landscape painting aesthetic and its influence. New Landscape Photography includes the works of Hong Lei, Lin Ran, Lu Yanpeng, Shao Wenhuan, Taca Sui, Xiao Xuan’an, Yan Changjiang, Yang Yongliang, Yao Lu, Zeng Han, Gao Hui, and Feng Yan, who express their thoughts on the role of mountains in society. -

PDF Download Art and Technique of Sumi-E Japanese Ink-Painting

ART AND TECHNIQUE OF SUMI-E JAPANESE INK- PAINTING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kay Morrissey Thompson | 72 pages | 15 Sep 2008 | Tuttle Publishing | 9780804839846 | English | Boston, United States Art and Technique of Sumi-e Japanese Ink-painting PDF Book Sat, Oct 31, pm - pm Eastern Time Next start dates 2. Know someone who would like this class but not sure of their schedule? Animals is one category of traditional East Asian brush painting. Dow strived for harmonic compositions through three elements: line, shading, and color. I think I'll give it a try! Kay Morrissey Thompson. When the big cloud brush rains down upon the paper, it delivers a graded swath of ink encompassing myriad shades of gray to black. He is regarded as the last major artist in the Bunjinga tradition and one of the first major artists of the Nihonga style. Landscape - There are many styles of painting landscape. Art Collectors Expand the sub menu. See private group classes. Get it first. Modern sumi-e includes a wide range of colors and hues alongside the shades of blackand the canvas for the paintings were done on rice paper. Ready to take this class? Depending on how much water is used, the artist could grind for five minutes or half an hour. Japanese Spirit No. First, it was Chinese art in the 16th Century and Chinese painting and Chinese arts tradition which was especially influential at a number of points. Want to Read saving…. Nancy Beals rated it liked it Aug 17, Different brushes have different qualities. PJ Ebbrell rated it really liked it Mar 29, Raymond Rickels rated it really liked it Oct 18, Submit the form below and we'll get back to you within 2 business hours with pricing and availability. -

Yang Yongliang Artworks

GALERIE PARIS-BEIJING YANG YONGLIANG ARTWORKS Travelers Among Mountains and steams, 2014 Lightbox Size A: 130 x 150 cm Size B: 200 x 100 cm From the New World, 2014 Photography Size A: 400 x 800 cm Size B: 300 x 600 cm Size C: 200 x 400 cm Crocodile and Shotgun, 2012 Lightbox Size A: 100 x 179 cm Size B: 66 x 118 cm Scorpion and Missile, 2012 Lightbox Size A: 100 x 179 cm Size B: 66 x 118 cm Snake and Grenade, 2012 Lightbox Size A: 100 x 179 cm Size B: 66 x 118 cm Enjoyment of the Moonlight, 2011 Size A: 82 x 225 cm Size B: 55 x 170 cm Size C: 41 x 127 cm An Elegant Assembly of Literati, 2011 Size A: 95 x 321 cm Size B: 64 x 219 cm Size C: 43 x 146 cm Broken Bridge, 2011 Size A: 90 x 260 cm Size B: 60 x 173 cm Size C: 40 x 115 cm Horse-Herder, 2011 Size A: 160 x 300 cm Size B: 70 x 200 cm Size C: 47 x 133 cm Lonely Anglerm, 2011 Size A: 80 x 245 cm Size B: 53 x 163 cm Size C: 40 x 122 cm YANG YONGLIANG I GALERIE PARIS-BEIJING Born in Shanghai in 1980, China Currently lives and works in Shanghai, China SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 «Yang Yongliang Solo Exhibition», Galerie Paris-Beijing, Brussels, Belgium 2014 «Yang Yongliang Solo Exhibition», Art Basel Hong Kong, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Hong Kong «Yang Yongliang Solo Exhibition», Sophie Maree Gallery, Den Haag, The Netherland 2013 «The Silent Valley», Galerie Paris-Beijing, Paris, France «Silent Valley», MC2 Gallery, Milan, Italy «Moonlight Metropolis», Schoeni Art Gallery, Hong Kong 2012 «The Peach Blossom Colony», Galerie Paris-Beijing, Paris, France «The Peach Blossom Colony», LIMN Art -

Download the Lesson Plan

ANCHORAGE MUSEUM GRADES K-6 DIANA TILLION GRANDFATHER HEMLOCK, 1971 Octopus ink, paper 1971.205.001 Education Department • 625 C St. Anchorage, AK 99501 • anchoragemuseum.org ACTIVITY AT A GLANCE In this activity, students will learn about color values such as tone, tint, and shade. Students will make careful observations to create a piece using variations of a single hue. GRANDFATHER HEMLOCK Begin by looking closely at the painting Grandfather Hemlock. If you are investigating the artwork with another person, use the questions below to guide your discussions. If you are working alone, consider recording your thoughts on paper: CLOSE-LOOKING Look closely, quietly at the artwork for a few minutes. OBSERVE Share your observations about the artwork or record your initial thoughts ASK • What do I notice about the artwork • What colors and materials does the artist use? • What moods do the artworks create? • What does it remind you of? • What more do you see? • What more can you find? DISCUSS USE 20 Questions Deck for more group discussion questions about the artwork. LEARN MORE ARTIST BIOGRAPHY Diana Tillion (1928-2010) moved to Alaska with her family in the Matanuska Valley in 1939. Three years later, her family would move again to Homer, where Tillion graduated high school. Tillion’s talent for art was noticed in her youth, in which she earned one hundred dollars to paint a mural, a sum equivalent to over a thousand dollars today. After graduating, Tillion began studying art in 1950 through correspondence as the road system did not yet reach the lower half of the Kenai Peninsula. -

Chipgan: a Generative Adversarial Network for Chinese Ink Wash Painting Style Transfer

ChipGAN: A Generative Adversarial Network for Chinese Ink Wash Painting Style Transfer Bin He1, Feng Gao2, Daiqian Ma1;3, Boxin Shi1, Ling-Yu Duan1∗ National Engineering Lab for Video Technology, Peking University, Beijing, China1 The Future Lab, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China2 SECE of Shenzhen Graduate School, Peking University, Shenzhen, China3 [email protected],[email protected],{madaiqian,shiboxin,lingyu}@pku.edu.cn ABSTRACT Style transfer has been successfully applied on photos to gener- Gatys et al. ate realistic western paintings. However, because of the inherently Oli different painting techniques adopted by Chinese and western paint- C h ings, directly applying existing methods cannot generate satisfac- input photo I ip Generated Western Painting Real Western Painting nk G W A a N tory results for Chinese ink wash painting style transfer. This paper Gatys et al. Ink Wash sh proposes ChipGAN, an end-to-end Generative Adversarial Network based architecture for photo to Chinese ink wash painting style transfer. The core modules of ChipGAN enforce three constraints – voids, brush strokes, and ink wash tone and diffusion – to address three key techniques commonly adopted in Chinese ink wash paint- ing. We conduct stylization perceptual study to score the similarity Generated Ink Wash Painting Generated Ink Wash Painting Real Chinese Painting of generated paintings to real paintings by consulting with pro- Figure 1: Given an input photo, existing style transfer tech- fessional artists based on the newly built Chinese ink wash photo nique (Gatys et al. [11]) is able to generate western paint- and image dataset. The advantages in visual quality compared with ing with visually close style to the real painting (top row), state-of-the-art networks and high stylization perceptual study but not for the Chinese ink wash painting (bottom left). -

Xue Susu (1573-Ca.1650) Was a Courtesan Who Lived in the Final Years of the Ming Dynasty

ESTEEMED LINK: AN ARGUMENT FOR XUE SUSU AS LITERATI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2011 By Cordes McMahan Hoffman Thesis Committee: Kate Lingley, Chairperson John Szostak Paul Lavy Xue Susu (1573-ca.1650) was a courtesan who lived in the final years of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). She was a multi-faceted artist, known for her painting, poetry and heroic personal- ity. An active participant in literati culture for most of her life, Xue’s body of work contains sev- eral outstanding paintings which demonstrate her grasp of the artistic concerns of literati painting practice at that time. Modern scholarship of Chinese women artists is a growing field, and it is now unthinkable to exclude women in the broad category of Chinese painting. However, examinations of individual artists, have been limited. For example, Xue Susu has been the subject of articles by Tseng Yu- ho (Betty Ecke); she was featured in an encyclopedic exhibition of Chinese women painters titled Views from Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists 1300-1912, and she is listed in several survey texts of Chinese art history.1 These considerations of Xue Susu demonstrate that modern scholarship acknowledges her as a talented painter. However, Xue is usually only considered in aggregate with other women painters with the grouping, gender being the primary identifier for artistic identity. The problem at hand then becomes that the majority of Xue Susu’s surviving work is dissimilar in stylistic choice to the general group of female painters of her era. -

Edward Burtynsky, Jiang Zhi, Shyu Ruey-Shiann, Gao Brothers, Cai Guo-Qiang “Nice Painting” in Hong Kong Et Al

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2012 V OLUME 11, NUMBER 6 INSI DE Artist Features: Edward Burtynsky, Jiang Zhi, Shyu Ruey-Shiann, Gao Brothers, Cai Guo-Qiang “Nice Painting” in Hong Kong et al. Contemporary Art Spaces in Xi’an Vitamin: A Conversation with Zhang Wei and Hu Fang Possibilities for the Page: Artist’s Books US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRI NTED IN TA I WAN 6 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 6, NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2012 CONTENTS Editor’s Note 34 Contributors 6 Displaced Cultural Landscape and Manufactured Landscapes: The Three Gorges Project in Art Zhou Yan 15 "Nice painting" et al. – Different Kinds of Painting and Related Practices in Hong Kong Frank Vigneron 41 34 Jiang Zhi’s Faulty Display Mathieu Borysevicz 41 Gleaned Memories: The Art of Shyu Ruey- Shiann Gilles Guillot 48 The Gao Brothers and The Execution of Christ: A Conversation Voon Pow Bartlett, Le Guo, Carrie Scott, Sheng Qi, and Haili Sun 61 61 Leaving Chang’an: Establishing Contemporary Art Spaces in the Ancient Capital Yang Wang 70 The Institution of Forgetting? Contemporary Chinese Art, Crititque, and the Academy Julian Scarff 83 Nutrition Spaces: Vitamin, Guangzhou, and Beijing 83 Edward Sanderson 92 Possibilites for the Page: 88BOOKS and Artists' Books in China Joni Low 103 Cai Guo-Qiang: Sky Ladder Orianna Cacchione 110 Chinese Name Index Cover: Cai Guo-Qiang, Crop Circles, (detail), 2012, reeds, 103 plywood, approximately 800 x 3600 cm. Photo: Joshua White/ JWPictures.com. Courtesy of the artist and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Canadian Foundation of Asian Art, Mr. -

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill Note: The image numbers in these lecture notes do not exactly coincide with the images onscreen but are meant to be reference points in the lectures’ progression. Lecture 10A: Bird and Flower Painting: The Early Centuries This will be the first of two lectures on Chinese bird‐and‐flower painting through the Song dynasty—this one taking us up to around the time of the Emperor Huizong in the late Northern Song; the next one, 10B, will be on Huizong‐period and Southern Song bird‐and‐flower painting. In one respect, these lectures have been inconsistent—well, more than one, but one I want to speak about briefly. I announced near the beginning that they would be heavily visual, without trying to deal seriously with questions of meaning and function, what the paintings meant to the people who made and used them, how they functioned in different times and different contexts. Well, Iʹve followed that generally; but Iʹve also spent quite a lot of time talking about the philosophical system that I take to underlie Chinese landscape painting in the different periods. I believe I have things to say about that topic that arenʹt general knowledge, and landscape painting is the principal theme of this series. But I wonʹt try anything of the kind for bird‐and‐flower painting. There are rich textual sources, in Chinese and in modern scholarship, about the symbolism of these subjects, and how pictures of them could carry symbolic significance. But that isnʹt a matter on which I feel I have original things to say, so I leave it alone. -

Zen As a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries

Zen as a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries by Meng Ying Fan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Meng Ying Fan 2020 Zen as a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries Meng Ying Fan Master of Arts Department of East Asia Studies University of Toronto 2020 Abstract This essay explores the impact of Chan/Zen on the art of landscape painting in China and Japan via literary/visual materials from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. By rethinking the aesthetic significance of “Zen painting” beyond the art and literary genres, this essay investigates how the Chan/Zen culture transformed the aesthetic attitudes and technical manifestations of picturing the landscapes, which are related to the philosophical thinking in mind. Furthermore, this essay emphasizes the problems of the “pattern” in Muromachi landscape painting to criticize the arguments made by D.T. Suzuki and his colleagues in the field of Zen and Japanese art culture. Finally, this essay studies the cultural interaction of Zen painting between China and Japan, taking the traveling landscape images of Eight Views of Xiaoxiang by Muqi and Yujian from China to Japan as a case. By comparing the different opinions about the artists in the two regions, this essay decodes the universality and localizations of the images of Chan/Zen. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratefulness to Professor Johanna Liu, my supervisor and mentor, whose expertise in Chinese aesthetics and art theories has led me to pursue my MA in East Asian studies. -

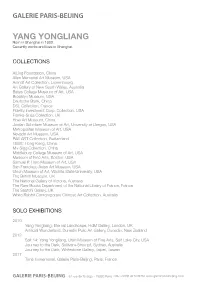

YANG YONGLIANG Born in Shanghai in 1980

GALERIE PARIS-BEIJING YANG YONGLIANG Born in Shanghai in 1980. Currently works and lives in Shanghai. COLLECTIONS AiLing Foundation, China Allen Memorial Art Museum, USA Arendt Art Collection, Luxembourg Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia Bates College Museum of Art, USA Brooklyn Museum, USA Deutsche Bank, China DSL Collection, France Fidelity Investment Corp. Collection, USA Franks-Suss Collection, UK How Art Museum, China Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, USA Metropolitan Museum of Art, USA Nevada Art Museum, USA PAE ART Collection, Switzerland HSBC Hong Kong, China M+ Sigg Collection, China Middlebury College Museum of Art, USA Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, USA San Francisco Asian Art Museum, USA Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University, USA The British Museum, UK The National Gallery of Victoria, Australia The Rare Books Department of the National Library of France, France The Saatchi Gallery, UK White Rabbit Contemporary Chinese Art Collection, Australia SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Yang Yongliang: Eternal Landscape, HdM Gallery, London, UK Artificial Wonderland, Dunedin Pulic Art Gallery, Dunedin, New Zealand 2018 Salt 14: Yang Yongliang, Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City, USA Journey to the Dark, Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney, Australia Journey to the Dark, Whitestone Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan 2017 Time Immemorial, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Paris, France GALERIE PARIS-BEIJING 62 rue de Turbigo - 75003 Paris ITEL: +33 (0)1 42 74 32 36 I www.galerieparisbeijing.com Time Immemorial,