Arxiv:0904.3349V1 [Math.HO] 21 Apr 2009 an Audience of One, and He Would Interrupt Whenever There Was a Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josiah Willard Gibbs

GENERAL ARTICLE Josiah Willard Gibbs V Kumaran The foundations of classical thermodynamics, as taught in V Kumaran is a professor textbooks today, were laid down in nearly complete form by of chemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Josiah Willard Gibbs more than a century ago. This article Science, Bangalore. His presentsaportraitofGibbs,aquietandmodestmanwhowas research interests include responsible for some of the most important advances in the statistical mechanics and history of science. fluid mechanics. Thermodynamics, the science of the interconversion of heat and work, originated from the necessity of designing efficient engines in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Engines are machines that convert heat energy obtained by combustion of coal, wood or other types of fuel into useful work for running trains, ships, etc. The efficiency of an engine is determined by the amount of useful work obtained for a given amount of heat input. There are two laws related to the efficiency of an engine. The first law of thermodynamics states that heat and work are inter-convertible, and it is not possible to obtain more work than the amount of heat input into the machine. The formulation of this law can be traced back to the work of Leibniz, Dalton, Joule, Clausius, and a host of other scientists in the late 17th and early 18th century. The more subtle second law of thermodynamics states that it is not possible to convert all heat into work; all engines have to ‘waste’ some of the heat input by transferring it to a heat sink. The second law also established the minimum amount of heat that has to be wasted based on the absolute temperatures of the heat source and the heat sink. -

The Tragedy of Grassmann Séminaire De Philosophie Et Mathématiques, 1979, Fascicule 2 « the Tragedy of Grassmann », , P

Séminaire de philosophie et mathématiques J. DIEUDONNÉ The Tragedy of Grassmann Séminaire de Philosophie et Mathématiques, 1979, fascicule 2 « The Tragedy of Grassmann », , p. 1-14 <http://www.numdam.org/item?id=SPHM_1979___2_A1_0> © École normale supérieure – IREM Paris Nord – École centrale des arts et manufactures, 1979, tous droits réservés. L’accès aux archives de la série « Séminaire de philosophie et mathématiques » implique l’accord avec les conditions générales d’utilisation (http://www.numdam.org/conditions). Toute utilisation commerciale ou impression systématique est constitutive d’une infraction pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit contenir la présente mention de copyright. Article numérisé dans le cadre du programme Numérisation de documents anciens mathématiques http://www.numdam.org/ - 1 - The Tragedy of Grassmann I. GRASSMANN'S LIFE In Ihc whole gallery of prominent mathematicians who, since the time of the Greeks, have left their mark on science, Hermann Grassmann certainly stands out as the most exceptional in many respects. When compared with other mathematicians, his career is an uninterrupted succession of oddities: unusual were his studies; unusual his mathematical style; highly unusual his own belated realization of his powers as a mathematician; unusual and unfortunate the total lack of understanding of his ideas, not only during his lifetime but long after his death; deplorable the neglect which compelled him to remain all his life professor in a high-school ("Gymnasiallehrer") when far lesser men occupied University positions; and the shroud of ignorance and uncertainty still surrounds his life and works in the minds of most mathematicians of our time, even when they put his original ideas to daily use. -

Grassmann's Vision

In: Hermann Gunther Grasmann (1809-1877): Visionary Mathematician, Scientist and Neohumanist Scholar, 1996 (Gert Schubring, Ed.), Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht/Boston 191–201. GRASSMANN’S VISION David Hestenes Abstract. Hermann Grassmann is cast as a pivotal gure in the historical development of a universal geometric calculus for mathematics and physics which continues to this day. He formulated most of the basic ideas and, to a remarkable extent, anticipates later developments. His inuence is far more potent and pervasive than generally recognized. After nearly a century on the brink of obscurity, Hermann Grassmann is widely recognized as the originator of Grassmann algebra, an indispensable tool in modern mathematics. Still, in conception and applications, conventional renditions of his exterior algebra fall far short of Grassmann’s original vision. A fuller realization of his vision is found in other mathematical developments to which his name is not ordinarily attached. This Sesquicen- tennial Celebration of Grassmann’s great book, Die Lineale Ausdehnungslehre [1], provides the opportunity for a renewed articulation and assessment of Grassmann’s vision. Grassmann is a pivotal gure in the historical evolution of a mathematical language to characterize human understanding of the physical world. Since quantitative concepts of space and time are fundamental to that understanding, the language is fundamentally geometrical and can best be described as a geometric calculus. For the most part the evo- lution of geometric calculus has been tacit and piecemeal, with many individuals achieving isolated results in response to isolated problems. Grassmann is pivotal in this historical process because he made it explicit and programmatic. In no uncertain terms, he declared the goal of his research on extension theory [1] as no less than the creation of a universal instrument for geometric research. -

The Exterior Algebra and Central Notions in Mathematics

The Exterior Algebra and Central Notions in Mathematics Gunnar Fløystad Dedicated to Stein Arild Strømme (1951–2014) The neglect of the exterior algebra is the mathematical tragedy of our century. —Gian-Carlo Rota, Indiscrete Thoughts (1997) his note surveys how the exterior algebra the somewhat lesser-known regressive product on and deformations or quotients of it the exterior algebra, which intuitively corresponds capture essences of five domains in to intersection of linear spaces. It relates this to mathematics: geometry and it also shows how analysis may T be extended to functions of extensive quantities. • Combinatorics •Mathematical physics Only in the last two decades of the 1800s did • Topology •Algebraic geometry publications inspired by Grassmann’s work achieve • Lie theory a certain mass. It may have been with some regret The exterior algebra originated in the work that Grassmann in his second version had an of Hermann Grassmann (1809–1877) in his book exclusively mathematical form, since he in the Ausdehnungslehre from 1844, and the thoroughly foreword says “[extension theory] is not simply one revised 1862 version, which now exists in an English among the other branches of mathematics, such translation [20] from 2000. Grassmann worked as algebra, combination theory or function theory, as a professor at the gymnasium in Stettin, then bur rather surpasses them, in that all fundamental Germany. Partly because Grassmann was an original elements are unified under this branch, which thinker and maybe partly because his education thus as it were forms the keystone of the entire had not focused much on mathematics, the first structure of mathematics.” edition of his book had a more philosophical The present note indicates that he was not quite than mathematical form and therefore gained little off the mark here. -

Whitney Algebras and Grassmann's Regressive Products

Whitney algebras and Grassmann’s regressive products Andrea Brini and Francesco Regonati Dipartimento di Matematica “Alma Mater Studiorum” Universit`adegli Studi di Bologna October 18, 2018 Abstract Geometric products on tensor powers Λ(V )⊗m of an exterior algebra and on Whitney algebras [13] provide a rigorous version of Grassmann’s regressive products of 1844 [17]. We study geometric products and their relations with other classical operators on exterior algebras, such as the Hodge ∗−operators and the join and meet products in Cayley-Grassmann algebras [2, 30]. We establish encodings of tensor powers Λ(V )⊗m and of Whitney algebras W m(M) in terms of letterplace algebras and of their geometric products in terms of divided powers of polarization operators. We use these encodings to provide simple proofs of the Crapo and Schmitt exchange relations in Whitney algebras and of two typical classes of identities in Cayley-Grassmann algebras . arXiv:1010.2964v1 [math.CO] 14 Oct 2010 We thank Henry Crapo and William Schmitt for their advice, encouragement, and invaluable suggestions Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 The algebras: generalities 5 3 The algebras: basic constructions 6 3.1 Cayley-Grassmannalgebras . .. .. 6 3.2 Tensorpowersofexterioralgebras. 7 3.3 Whitneyalgebras .............................. 11 1 4 Relations among the algebras 12 4.1 From tensor powers of exterior algebras to CG-Algebras . .... 12 4.2 From Whitney algebras to tensor powers of exterior algebras. .... 12 5 The Hodge operators 13 5.1 The Hodge ∗−operators .......................... 13 5.2 ThegeneralizedHodgeoperators . 15 6 Letterplace algebras and polarization operators 17 6.1 Skew-symmetric Letterplace algebras and place polarization operators. -

Functions of Multivector Variables Plos One, 2015; 10(3): E0116943-1-E0116943-21

PUBLISHED VERSION James M. Chappell, Azhar Iqbal, Lachlan J. Gunn, Derek Abbott Functions of multivector variables PLoS One, 2015; 10(3): e0116943-1-e0116943-21 © 2015 Chappell et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited PERMISSIONS http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ http://hdl.handle.net/2440/95069 RESEARCH ARTICLE Functions of Multivector Variables James M. Chappell*, Azhar Iqbal, Lachlan J. Gunn, Derek Abbott School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia * [email protected] Abstract As is well known, the common elementary functions defined over the real numbers can be generalized to act not only over the complex number field but also over the skew (non-com- muting) field of the quaternions. In this paper, we detail a number of elementary functions extended to act over the skew field of Clifford multivectors, in both two and three dimen- sions. Complex numbers, quaternions and Cartesian vectors can be described by the vari- ous components within a Clifford multivector and from our results we are able to demonstrate new inter-relationships between these algebraic systems. One key relation- ship that we discover is that a complex number raised to a vector power produces a quater- nion thus combining these systems within a single equation. We also find a single formula that produces the square root, amplitude and inverse of a multivector over one, two and three dimensions. -

Introduction to Geometric Algebra

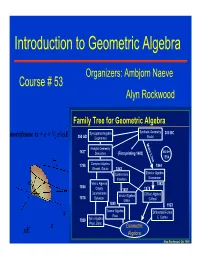

Introduction to Geometric Algebra Organizers: Ambjorn Naeve Course # 53 Alyn Rockwood Family Tree for Geometric Algebra 1 2 Syncopated Algebra Synthetic Geometry 300 BC metriframe (x + e + /2 x e)E 250 AD Diophantes Euclid Main Line Analytic Geometry 1637 Descartes (First printing 1482) Boole 1854 1798 Complex Algebra 1844 Wessel, Gauss 1843 Quaternions Exterior Algebra Hamilton Grassmann e Matrix Algebra 1862 * 1854 Cayley 1881 1878 Determinants Vector Algebra Clifford Algebra 1878 Sylvester Gibbs Clifford 1890 1923 x Tensor Algebra Differential Forms Ricci E. Cartan 1928 Spin Algebra e Pauli, Dirac Geometric xE Algebra Alyn Rockwood, Oct 1999 Course Speakers Alyn Rockwood (Colorado School of Mines) David Hestenes (Arizona State University) Leo Dorst (University of Amsterdam) Stephen Mann (University of Waterloo) Joan Lasenby (Cambridge University) Chris Doran (Cambridge University) Ambjørn Naeve (Royal Technical Institute of Stockholm) [a] mathematician is a Platonist on weekdays and a Formalist on Sundays. That is, when doing mathematics he is convinced that he is dealing with objective reality … when challenged to give a philosophical account of this reality, he finds it easiest to pretend that he does not believe in it after all. ~P. Davis Mathematics is Language Primitive Nouns Verbs scalar, vector scalar, dot & cross products, Vector Algebra scalar & vector addition gradient, curl, … real, imaginary addition, multiplication, Complex Analysis conjugation, … points, line, circles … intersection, union, … Synthetic Geometry A Redundant -

Geometric Algebra and Its Application to Mathematical Physics

Geometric Algebra and its Application to Mathematical Physics Chris J. L. Doran Sidney Sussex College A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Cambridge. February 1994 Preface This dissertation is the result of work carried out in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics between October 1990 and October 1993. Sections of the dissertation have appeared in a series of collaborative papers [1] —[10]. Except where explicit reference is made to the work of others, the work contained in this dissertation is my own. Acknowledgements Many people have given help and support over the last three years and I am grateful to them all. I owe a great debt to my supervisor, Nick Manton, for allowing me the freedom to pursue my own interests, and to my two principle collaborators, Anthony Lasenby and Stephen Gull, whose ideas and inspiration were essential in shaping my research. I also thank David Hestenes for his encouragement and his company on an arduous journey to Poland. Above all, I thank Julie Cooke for the love and encouragement that sustained me through to the completion of this work. Finally, I thank Stuart Rankin and Margaret James for many happy hours in the Mill, Mike and Rachael, Tim and Imogen, Paul, Alan and my other colleagues in DAMTP and MRAO. I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the SERC, DAMTP and Sidney Sussex College. To my parents Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Some History and Recent Developments . 4 1.2 Axioms and Definitions . 9 1.2.1 The Geometric Product . -

From Grassmann's Vision to Geometric Algebra Computing

From Grassmann's vision to Geometric Algebra Computing Dietmar Hildenbrand 1. Introduction What mathematicians often call Cli®ord algebra is called geometric algebra if the focus is on the geometric meaning of the algebraic expressions and opera- tors. Geometric algebra is a mathematical framework to easily describe geomet- ric concepts and operations. It allows us to develop algorithms fast and in an intuitive way. Geometric algebra is based on the work of Hermann Grassmann Figure 1. Two trends towards what we call geometric algebra computing. [Grassmann, 1862] and his vision of a general mathematical language for geometry. William Cli®ord combined Grassmann's exterior algebra and Hamilton's quater- nions [Cli®ord, 1882a], [Cli®ord, 1882b]. Pioneering work has been done by David Hestenes, who ¯rst applied geometric algebra to problems in mechanics and physics [Hestenes and Sobczyk, 1984] [Hestenes, 1986]. His work was culminating some years ago in the invention of conformal geometric algebra [Hestenes, 2001]. Grass- mann's outer product leads to high dimensional multivectors. Currently, we can 2 Dietmar Hildenbrand recognize a shift from single processor platforms to parallel computing platforms which are able to treat these multivectors in an e±cient way. During the past decades, especially from 1986 until 2002, processor performance doubled every 18 months. Currently, this improvement law is no longer valid because of technical limitations. The new trend to parallel systems will most likely dominate the future. Thanks to multi-core architectures or powerful graphics boards for instance based on the CUDA technology from NVIDIA, the ATI stream technology of AMD or on the future Larrabee technology of INTEL, one can expect impressive results using the powerful language of geometric algebra. -

HERMANN GRASSMANN (April 4, 1809 – September 26, 1877) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany

HERMANN GRASSMANN (April 4, 1809 – September 26, 1877) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany Today he is regarded as one of the most important mathematicians of the 19th century; during his lifetime, essentially only his contributions to the study of Sanskrit, the ancient Indian language, were recognised. HERMANN GÜNTHER GRASSMANN was born in Stettin, the third of twelve children of a grammar school teacher of mathematics and physics. During his schooling he did not stand out for his exceptional achievements and at times his father even considered letting him learn a trade. Towards the end of his school years, however, the young man blossomed. As the second best pupil in his year, HERMANN left school to study theology in Berlin (influenced by his maternal grandfather, who was a Protestant pastor). He also attended lectures in philosophy and the ancient languages – mathematics and physics played no part. In the autumn of 1830 he returned home and he did not pursue possible thoughts of working as a pastor at first. Instead, he decided to pursue a profession as a teacher of mathematics and physics at the Gymnasium. For a year he prepared for the exams in Berlin – without ever having heard lectures in the subjects before. His level of knowledge did not seem to have satisfied the examination board – he only received a teaching permit for the lower classes and the option to repeat the examination. From spring 1832 onwards, he worked as an assistant teacher at the Gymnasium in Stettin. In 1834 he passed the first stage of theology examinations for prospective pastors at the Council of the Lutheran Church in Stettin, but then decided to take up a post in Berlin as a mathematics teacher at the Gewerbeschule (a kind of secondary school) previously held by JACOB STEINER. -

Lecture 17: Color

Matthew Schwartz Lecture 17: Color 1 History of Color You already know that wavelengths of light have different colors. For example, red light has λ ≈ 650nm, blue light has λ ≈ 480nm and purple light has λ ≈ 420nm. But there is much more to color than pure monochromatic light. For example, why does mixing red paint and blue paint make purple paint? Surely monochromatic plane waves can’t suddenly change wavelength, so what is going on when we mix colors? Also, there are colors (like cyan or brown) which do not appear in the rainbow. What wavelengths do they have? As we will see, the wavelength of monochromatic light is only the starting point for thinking about color. What we think of as a color depends on the way our brains and our visual system processes the light coming into our eyes. The earliest studies of color were done by Newton. He understood that white light was a combination of lots of wavelengths. He performed some ingenious experiments to show this, described in his book Optiks (1704). For example, even though prisms turned white light into a rainbow, people thought that maybe the prism was producing the rainbow colors. Newton showed that this wasn’t true. He could use lenses and mirrors to shine only red light into a prism, then only red light came out. He also separated white light into different colors, then used lenses and mirrors to put them into another prism which made white light again In his classic Optiks, Newton compared the colors going in a circle to the cycle of 5ths in music. -

The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann Von Helmholtz Peter Skiff Bard College

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Faculty Books & Manuscripts Bard Faculty Publications 2016 The hP ysicist - Philosophers: The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann von Helmholtz Peter Skiff Bard College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.bard.edu/facbooks Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Skiff, Peter, "The hP ysicist - Philosophers: The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann von Helmholtz" (2016). Faculty Books & Manuscripts. 1. http://digitalcommons.bard.edu/facbooks/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Bard Faculty Publications at Bard Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books & Manuscripts by an authorized administrator of Bard Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHYSICIST - PHILOSOPHERS The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann von Helmholtz Peter Skiff Bard College, 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was begun 25 years into a 50 year career at Bard College. This position gave me access to an extraordinary range of exceptional faculty, distinguished visiting scholars, and brilliant student researchers, all of whom inspired and informed im investigating academic fields I pursued: mathematical physics and the history and philosophy of science. In addition the editors of the American Library Association’s Choice magazine provided literally hundreds of books for review for college libraries. It is from this trove of ideas and information I have been assembling this book. I am particularly grateful to particular advice and information from Hannah Arendt, Heinrich Bluecher, Irma Brandeis, and A.