The Challenge of the Changing Same: the Jazz Avant-Garde of the 1960S, the Black Aesthetic, and the Black Arts Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

Here I Played with Various Rhythm Sections in Festivals, Concerts, Clubs, Film Scores, on Record Dates and So on - the List Is Too Long

MICHAEL MANTLER RECORDINGS COMMUNICATION FONTANA 881 011 THE JAZZ COMPOSER'S ORCHESTRA Steve Lacy (soprano saxophone) Jimmy Lyons (alto saxophone) Robin Kenyatta (alto saxophone) Ken Mcintyre (alto saxophone) Bob Carducci (tenor saxophone) Fred Pirtle (baritone saxophone) Mike Mantler (trumpet) Ray Codrington (trumpet) Roswell Rudd (trombone) Paul Bley (piano) Steve Swallow (bass) Kent Carter (bass) Barry Altschul (drums) recorded live, April 10, 1965, New York TITLES Day (Communications No.4) / Communications No.5 (album also includes Roast by Carla Bley) FROM THE ALBUM LINER NOTES The Jazz Composer's Orchestra was formed in the fall of 1964 in New York City as one of the eight groups of the Jazz Composer's Guild. Mike Mantler and Carla Bley, being the only two non-leader members of the Guild, had decided to organize an orchestra made up of musicians both inside and outside the Guild. This group, then known as the Jazz Composer's Guild Orchestra and consisting of eleven musicians, began rehearsals in the downtown loft of painter Mike Snow for its premiere performance at the Guild's Judson Hall series of concerts in December 1964. The orchestra, set up in a large circle in the center of the hall, played "Communications no.3" by Mike Mantler and "Roast" by Carla Bley. The concert was so successful musically that the leaders decided to continue to write for the group and to give performances at the Guild's new headquarters, a triangular studio on top of the Village Vanguard, called the Contemporary Center. In early March 1965 at the first of these concerts, which were presented in a workshop style, the group had been enlarged to fifteen musicians and the pieces played were "Radio" by Carla Bley and "Communications no.4" (subtitled "Day") by Mike Mantler. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

QUASIMODE: Ike QUEBEC

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ QUASIMODE: "Oneself-Likeness" Yusuke Hirado -p,el p; Kazuhiro Sunaga -b; Takashi Okutsu -d; Takahiro Matsuoka -perc; Mamoru Yonemura -ts; Mitshuharu Fukuyama -tp; Yoshio Iwamoto -ts; Tomoyoshi Nakamura -ss; Yoshiyuki Takuma -vib; recorded 2005 to 2006 in Japan 99555 DOWN IN THE VILLAGE 6.30 99556 GIANT BLACK SHADOW 5.39 99557 1000 DAY SPIRIT 7.02 99558 LUCKY LUCIANO 7.15 99559 IPE AMARELO 6.46 99560 SKELETON COAST 6.34 99561 FEELIN' GREEN 5.33 99562 ONESELF-LIKENESS 5.58 99563 GET THE FACT - OUTRO 1.48 ------------------------------------------ Ike QUEBEC: "The Complete Blue Note Forties Recordings (Mosaic 107)" Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded July 18, 1944 in New York 34147 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.35 Blue Note 6507 37805 BLUE HARLEM 4.33 Blue Note 37 37806 INDIANA 3.55 Blue Note 38 39479 SHE'S FUNNY THAT WAY 4.22 --- 39480 INDIANA 3.53 Blue Note 6507 39481 BLUE HARLEM 4.42 Blue Note 544 40053 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.36 Blue Note 37 Jonah Jones -tp; Tyree Glenn -tb; Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Oscar Pettiford -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded September 25, 1944 in New York 37810 IF I HAD YOU 3.21 Blue Note 510 37812 MAD ABOUT YOU 4.11 Blue Note 42 39482 HARD TACK 3.00 Blue Note 510 39483 --- 3.00 prev. unissued 39484 FACIN' THE FACE 3.48 --- 39485 --- 4.08 Blue Note 42 Ike Quebec -ts; Napoleon Allen -g; Dave Rivera -p; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. -

4823C7a9d589da82e72837249d

RETURN TO THE EAST BROOKLYN RECLRIMS THE BLRCK RRT FORM KNOWN RS JRZZ I' IIlII£I SCIIII£I • B9 BllSIl MCHBII 'What you're about to hear is not jazz, or some other irrelevant term we allow others 10 use in defining our creation, but the sounds thai are about to saturate your being and serlsitize your soul is the continuing process of nationalist consciousness manifesting its message within the conlext of one of our strongest natural resources: Black music. What is represented on these jams is the crystallization of the role of Black music as a functional organ in the struggle for national liberation.. AJkebu-lan is the unfolding of this progress as mu!>ic-meaoing. It is sound-feeling." KwmbI. >PUI<Irc .... -_. on SUN-Uol his lpOkrn.word innoduuion amounl$ 10 :l m:o.ni- Kwasi Konadu'l r«mt book, Trulh Cru.sJKJ It> tIN &nh rrd:o.iming tlK Black nl form known u WiU RiM Api.., is the delining tome on lhe Ezsr.. h details T for uS/: ali :o.libn:aling. II2l1"P"rti..., vdlic:k. '1M do- lhecompln worIrinV ofhow the organiulion flourished for qurnl <kKript ion ofil :oJ :l -funuion,,1 organ- ckserillQ 1M o>'n adead... 1hc wt and iu primary k>c:o.tion at ,00aver mk of$('lUnd wilhin m.- Ezsr. organiu.ion wdl. MllSic Plac:c in Brooklyn WU n(K just a norefrom or musk hall, bul the blood pumping, mako i. as;"r m dig"". and a w::o.yoflifc.lhc Uhunf Food asan or. -

Hermann NAEHRING: Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: NAIMA: Mari

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Hermann NAEHRING: "Großstadtkinder" Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; Henry Osterloh -tymp; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24817 SCHLAGZEILEN 6.37 Amiga 856138 Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24818 SOUJA 7.02 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Volker Schlott -fl; recorded 1985 in Berlin A) Orangenflip B) Pink-Punk Frosch ist krank C) Crash 24819 GROSSSTADTKINDER ((Orangenflip / Pink-Punk, Frosch ist krank / Crash)) 11.34 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24820 PHRYGIA 7.35 --- 24821 RIMBANA 4.05 --- 24822 CLIFFORD 2.53 --- ------------------------------------------ Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: "Heart" Wlodzimierz Nahorny -as,p; Jacek Ostaszewski -b; Sergiusz Perkowski -d; recorded November 1967 in Warsaw 34847 BALLAD OF TWO HEARTS 2.45 Muza XL-0452 34848 A MONTH OF GOODWILL 7.03 --- 34849 MUNIAK'S HEART 5.48 --- 34850 LEAKS 4.30 --- 34851 AT THE CASHIER 4.55 --- 34852 IT DEPENDS FOR WHOM 4.57 --- 34853 A PEDANT'S LETTER 5.00 --- 34854 ON A HIGH PEAK -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

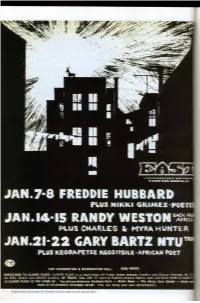

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

Dave Burrell, Pianist Composer Arranger Recordings As Leader from 1966 to Present Compiled by Monika Larsson

Dave Burrell, Pianist Composer Arranger Recordings as Leader From 1966 to present Compiled by Monika Larsson. All Rights Reserved (2017) Please Note: Duplication of this document is not permitted without authorization. HIGH Dave Burrell, leader, piano Norris Jones, bass Bobby Kapp, drums, side 1 and 2: b Sunny Murray, drums, side 2: a Pharoah Sanders, tambourine, side . Recording dates: February 6, 1968 and September 6, 1968, New York City, New York. Produced By: Alan Douglas. Douglas, USA #SD798, 1968-LP Side 1:West Side Story (L. Bernstein) 19:35 Side 2: a. East Side Colors (D. Burrell) 15:15 b. Margy Pargy (D. Burrell 2:58 HIGH TWO Dave Burrell, leader, arranger, piano Norris Jones, bass Sunny Murray, drums, side 1 Bobby Kapp, drums side 2. Recording Dates: February 6 and September 9, 1968, New York City, New York. Produced By: Alan Douglas. Additional production: Michael Cuscuna. Trio Freedom, Japan #PA6077 1969-LP. Side: 1: East Side Colors (D. Burrell) 15:15 Side: 2: Theme Stream Medley (D.Burrell) 15:23 a.Dave Blue b.Bittersweet Reminiscence c.Bobby and Si d.Margie Pargie (A.M. Rag) e.Oozi Oozi f.Inside Ouch Re-issues: High Two - Freedom, Japan TKCB-70327 CD Lions Abroad - Black Lion, UK Vol. 2: Piano Trios. # BLCD 7621-2 2-1996CD HIGH WON HIGH TWO Dave Burrell, leader, arranger, piano Sirone (Norris Jones) bass Bobby Kapp, drums, side 1, 2 and 4 Sunny Murray, drums, side 3 Pharoah Sanders, tambourine, side 1, 2, 4. Recording dates: February 6, 1968 and September 6, 1968, New York City, New York. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

French Stewardship of Jazz: the Case of France Musique and France Culture

ABSTRACT Title: FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE Roscoe Seldon Suddarth, Master of Arts, 2008 Directed By: Richard G. King, Associate Professor, Musicology, School of Music The French treat jazz as “high art,” as their state radio stations France Musique and France Culture demonstrate. Jazz came to France in World War I with the US army, and became fashionable in the 1920s—treated as exotic African- American folklore. However, when France developed its own jazz players, notably Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, jazz became accepted as a universal art. Two well-born Frenchmen, Hugues Panassié and Charles Delaunay, embraced jazz and propagated it through the Hot Club de France. After World War II, several highly educated commentators insured that jazz was taken seriously. French radio jazz gradually acquired the support of the French government. This thesis describes the major jazz programs of France Musique and France Culture, particularly the daily programs of Alain Gerber and Arnaud Merlin, and demonstrates how these programs display connoisseurship, erudition, thoroughness, critical insight, and dedication. France takes its “stewardship” of jazz seriously. FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE By Roscoe Seldon Suddarth Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2008 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard King, Musicology Division, Chair Professor Robert Gibson, Director of the School of Music Professor Christopher Vadala, Director, Jazz Studies Program © Copyright by Roscoe Seldon Suddarth 2008 Foreword This thesis is the result of many years of listening to the jazz broadcasts of France Musique, the French national classical music station, and, to a lesser extent, France Culture, the national station for literary, historical, and artistic programs. -

Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 "The planet is the way it is because of the scheme of words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1086 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] "THE PLANET IS THE WAY IT IS BECAUSE OF THE SCHEME OF WORDS": SUN RA AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RECKONING BY MARYAM IVETTE PARHIZKAR A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York. 2015 i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Thesis Adviser: ________________________________________ Ammiel Alcalay Date: ________________________________________ Executive Officer: _______________________________________ Matthew K. Gold Date: ________________________________________ THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract "The Planet is the Way it is Because of the Scheme of Words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning By Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Adviser: Ammiel Alcalay This constellatory essay is a study of the African American sound experimentalist, thinker and self-proclaimed extraterrestrial Sun Ra (1914-1993) through samplings of his wide, interdisciplinary archive: photographs, film excerpts, selected recordings, and various interviews and anecdotes.