Jeremy Collier the Younger: Life and Works, 1650-1726

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMES USSHER Copyright Material: Irish Manuscripts Commission

U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page i The Correspondence of JAMES USSHER Copyright material: Irish Manuscripts Commission Commission Manuscripts Irish material: Copyright U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page iii The Correspondence of JAMES USSHER 1600–1656 V O L U M E I I I 1640–1656 Commission Letters no. 475–680 editedManuscripts by Elizabethanne Boran Irish with Latin and Greek translations by David Money material: Copyright IRISH MANUSCRIPTS COMMISSION 2015 U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page iv For Gertie, Orla and Rosemary — one each. Published by Irish Manuscripts Commission 45 Merrion Square Dublin 2 Ireland www.irishmanuscripts.ie Commission Copyright © Irish Manuscripts Commission 2015 Elizabethanne Boran has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000, Section 107. Manuscripts ISBN 978-1-874280-89-7 (3 volume set) Irish No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. The index was completed with the support of the Arts andmaterial: Social Sciences Benefaction Fund, Trinity College, Dublin. Copyright Typeset by December Publications in Adobe Garamond and Times New Roman Printed by Brunswick Press Index prepared by Steve Flanders U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page v S E R I E S C O N T E N T S V O L U M E I Abbreviations xxv Acknowledgements xxix Introduction xxxi Correspondence of James Ussher: Letters no. -

John Durie (1596–1680): Defragmenter of the Reformation

7. Jahrgang MBS TEXTE 148 2010 George M. Ella John Durie (1596–1680): Defragmenter of the Reformation BUCER IN S T E M R A I N M A R 2 1 : E P 4 H ReformedReformiertes Forum Forum TableInhaltsverzeichnis of Contents Part One: Europe and Britain Working Together ..................... 3 Part Two: Ideas of Union Grow ................................................ 8 Part Three: Working for Cromwell ......................................... 14 Annotation ............................................................................. 20 The Author ............................................................................. 21 Impressum ............................................................................. 22 1. Aufl. 2010 John Durie (1596–1680): Defragmenter of the Reformation John Durie (1596–1680): Defragmenter of the Reformation George M. Ella Part One: Europe and is the modern man of God today who Britain Working Together is world-renowned as a great preacher, pastor, diplomat, educator, scientist, lin- Who on earth is John Durie? guist, translator, man of letters, ambas- Most computer users have experi- sador, library reformer, mediator and enced hard disks full of jumbled, frag- politician? Who today produces best- mented files which block spaces causing sellers on a monthly basis, writing in memory and retrieval problems. What half a dozen different languages? In all a relief it is to switch on a defragmenter these fields John Durie has been called and have everything made ship-shape ‘great’ or ‘the greatest’, yet he is forgot- again. The Reformation in mid-seven- ten by his mother country whom he teenth century Britain had reached such served so long and well. This is perhaps a fragmentation and a defragmenter was because it is beyond human imagination called for. The man for the job was cer- that such a man could have existed and tainly John Durie who was possibly the his ‘type’ today is not called for. -

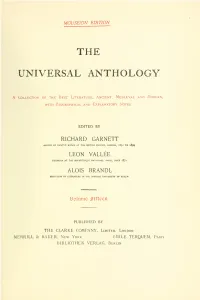

The Universal Anthology

MOUSEION EDITION THE UNIVERSAL ANTHOLOGY A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient, Medieval and Modern, WITH Biographical and Explanatory Notes EDITED BY RICHARD GARNETT KEEPER OF PRINTED BOOKS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, 185I TO 1899 LEON VALLEE LIBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQJJE NATIONALE, PARIS, SINCE I87I ALOIS BRANDL PKOFESSOR OF LITERATURE IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OP BERLIN IDoluine ififteen PUBLISHED BY THE CLARKE COMPANY, Limited, London MERRILL & BAKER. New York EMILE TERQUEM. Paris BIBLIOTHEK VERLAG, Berlin Entered at Stationers' Hall London, 1899 Droits de reproduction et da traduction reserve Paris, 1899 Alle rechte, insbesondere das der Ubersetzung, vorbehalten Berlin, 1899 Proprieta Letieraria, Riservate tutti i divitti Rome, 1899 Copyright 1899 by Richard Garnett IMMORALITY OF THE ENGLISH STAGE. 347 Young Fashion — Hell and Furies, is this to be borne ? Lory — Faith, sir, I cou'd almost have given him a knock o' th' pate myself. A Shoet View of the IMMORALITY AND PROFANENESS OF THE ENG- LISH STAGE. By JEREMY COLLIER. [Jeremy Collier, reformer, was bom in Cambridgeshire, England, in 1650. He was educated at Cambridge, became a clergyman, and was a " nonjuror" after the Revolution ; not only refusing the oath, but twice imprisoned, once for a pamphlet denying that James had abdicated, and once for treasonable corre- spondence. In 1696 he was outlawed for absolving on the scaffold two conspira- tors hanged for attempting William's life ; and though he returned later and lived unmolested in London, the sentence was never rescinded. Besides polemics and moral essays, he wrote a cyclopedia and an " Ecclesiastical IILstory of Great Britain," and translated Moreri's Dictionary. -

Title Page R.J. Pederson

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/22159 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Pederson, Randall James Title: Unity in diversity : English puritans and the puritan reformation, 1603-1689 Issue Date: 2013-11-07 Chapter 3 John Downame (1571-1652) 3.1 Introduction John Downame (or Downham) was one of the greatest exponents of the precisianist strain within Puritanism during the pre-revolutionary years of the seventeenth century, a prominent member of London Puritanism, and renowned casuist.1 His fame rests chiefly in his nineteen published works, most of which were works of practical divinity, such as his four-part magnum opus, The Christian Warfare (1604-18), and his A Guide to Godlynesse (1622), a shorter, though still copious, manual for Christian living. Downame was also known for his role in publishing two of the most popular theological manuals: Sir Henry Finch’s The Summe of Sacred Divinitie (1620), which consisted of a much more expanded version of Finch’s earlier Sacred Doctrine (1613), and Archbishop James Ussher’s A Body of Divinitie (1645), which was published from rough manuscripts and without Ussher’s consent, having been intended for private use.2 Downame also had a role in codifying the Westminster annotations on the Bible, being one of a few city ministers to work on the project, though he never sat at the Westminster Assembly.3 Downame’s older brother, 1 Various historians from the seventeenth century to the present have spelled Downame’s name differently (either Downame or Downham). The majority of seventeenth century printed works, however, use “Downame.” I here follow that practice. -

Old Ipswichian Journal

The journal of the Old Ipswichian Club Old Ipswichian Journal The Journal of the Old Ipswichian Club | Issue 8 2017 In this issue Club news • Features • Members’ news • Births, marriages, deaths and obituaries OI Club events • School news • From the archives • Programme of events Page Content 01 Member Leavers 2016 Life Members Year 13 Friar Emily Victoria Murray Dylan James Goldthorpe Oliver Pardoe Maximillian Thomas Ablett Emily Louise Goodwin Adam Robert Patel Elisha Yogeshkumar Adams Georgina Baddeley Gorham Emily Louise Patten Arthur George Alexander Hannah Gravell Oscar James Robert Phillips Tobias Edward Oliver Alfs Benjamin Ward Hamilton Michael Pickering Jack Frederick Ayre Scarlett Victoria Hardwick Eleanor Maisie Price Indigo Celeste Imogen Barlow Natasha Alice Harris Leo William Patrick Prickett James Robert Bartleet Henry Oliver Hills Matilda Kate Proud Faye Madeleine Blackmore Livia Constance Houston Caitlin Siobhan Putman Sebastian Joseph Boyle India Howard Ruby Eliza Rackham Isabelle Eve Broadway Charles Hudson Tobias James Riley James Mark Brown Isobel Poppy Hyam Brittany Lily-Ray Robson Tallulah Inger Mary Bryanton Alexander James Jiang Wenyuan Robson Eben Harry Campbell Oliver Thomas Jones William James Cresswell Rowbotham Emily Charlotte Cappabianca Mia Isabella Kemp Nathanael Jefferson Royle Emily Florence Carless-Frost Tabitha Kemp-Smith Teja Kim Rule Charlotte Elizabeth Chan Yat Hei Knight Jonathan Anthony Rush Tobias Charles Chen Yuepeng Christopher Shaikly Anna Cheng Pun Hong Knights William John Sharma Sasha -

I the POLITICS of DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS

THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 by Loring Pfeiffer B. A., Swarthmore College, 2002 M. A., University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Loring Pfeiffer It was defended on May 1, 2015 and approved by Kristina Straub, Professor, English, Carnegie Mellon University John Twyning, Professor, English, and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, Courtney Weikle-Mills, Associate Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, English ii Copyright © by Loring Pfeiffer 2015 iii THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 Loring Pfeiffer, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 The Politics of Desire argues that late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women playwrights make key interventions into period politics through comedic representations of sexualized female characters. During the Restoration and the early eighteenth century in England, partisan goings-on were repeatedly refracted through the prism of female sexuality. Charles II asserted his right to the throne by hanging portraits of his courtesans at Whitehall, while Whigs avoided blame for the volatility of the early eighteenth-century stock market by foisting fault for financial instability onto female gamblers. The discourses of sexuality and politics were imbricated in the texts of this period; however, scholars have not fully appreciated how female dramatists’ treatment of desiring female characters reflects their partisan investments. -

Seventeenth-Century Scribal Culture and “A Dialogue Between King James and King William”

76 THE JOURNAL OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY SCRIBAL CULTURE AND “A DIALOGUE BETWEEN KING JAMES AND KING WILLIAM” BY ERIN KELLY The latter portion of the seventeenth century saw the emergence of a number of institutions and practices whose existence we may take for granted in the modern era: the two-party parliamentary system pitted Whigs against Tories, the Royal Society formalized many aspects of empirical science, and the Stationers’ Company lost their monopoly over publication rights, effectively paving the way for modern copyright law. These changes emerged out of a tumultuous political context: England had been plunged into civil war in the middle of the century, and even the restoration of the monarchy did not entirely stifle those in parliament who opposed the monarch’s absolute power. The power struggle between the king and Parliament had a direct impact on England’s book industry: the first Cavalier Parliament of 1662 – only two years after the Restoration – revived the Licensing Act in an attempt to exercise power over what material was allowed to be printed. Through the act, the king could appoint a licenser to oversee the publication of books who could deny a license to any books thought to be objectionable.1 Roger L’Estrange, an arch-royalist, became Surveyor of the Presses, and later Licenser of the Press, and zealously exercised the power of these positions by hunting out unauthorized printing presses, suppressing seditious works, and censoring anti-monarchical texts.2 This was a dramatic change from the state of affairs prior to the Restoration, which had seen an explosion in the printing trade, when Parliament ostensibly exercised control over licensing, but did so through inconsistent laws and lax enforcement.3 The struggle between Parliament and the monarchy thus played itself out in part through a struggle for control over the censorship of the press. -

Preface Introduction: the Seven Bishops and the Glorious Revolution

Notes Preface 1. M. Barone, Our First Revolution, the Remarkable British Upheaval That Inspired America’s Founding Fathers, New York, 2007; G. S. de Krey, Restoration and Revolution in Britain: A Political History of the Era of Charles II and the Glorious Revolution, London, 2007; P. Dillon, The Last Revolution: 1688 and the Creation of the Modern World, London, 2006; T. Harris, Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685–1720, London, 2006; S. Pincus, England’s Glorious Revolution, Boston MA, 2006; E. Vallance, The Glorious Revolution: 1688 – Britain’s Fight for Liberty, London, 2007. 2. G. M. Trevelyan, The English Revolution, 1688–1689, Oxford, 1950, p. 90. 3. W. A. Speck, Reluctant Revolutionaries, Englishmen and the Revolution of 1688, Oxford, 1988, p. 72. Speck himself wrote the petition ‘set off a sequence of events which were to precipitate the Revolution’. – Speck, p. 199. 4. Trevelyan, The English Revolution, 1688–1689, p. 87. 5. J. R. Jones, Monarchy and Revolution, London, 1972, p. 233. Introduction: The Seven Bishops and the Glorious Revolution 1. A. Rumble, D. Dimmer et al. (compilers), edited by C. S. Knighton, Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series, of the Reign of Anne Preserved in the Public Record Office, vol. iv, 1705–6, Woodbridge: Boydell Press/The National Archives, 2006, p. 1455. 2. Great and Good News to the Church of England, London, 1705. The lectionary reading on the day of their imprisonment was from Two Corinthians and on their release was Acts chapter 12 vv 1–12. 3. The History of King James’s Ecclesiastical Commission: Containing all the Proceedings against The Lord Bishop of London; Dr Sharp, Now Archbishop of York; Magdalen-College in Oxford; The University of Cambridge; The Charter- House at London and The Seven Bishops, London, 1711, pp. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

English Literature 1590 – 1798

UGC MHRD ePGPathshala Subject: English Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Paper 02: English Literature 1590 – 1798 Paper Coordinator: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad Module No 31: William Wycherley: The Country Wife Content writer: Ms.Maria RajanThaliath; St. Claret College; Bangalore Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad William Wycherley’s The Country Wife Introduction This lesson deals with one of the most famous examples of Restoration theatre: William Wycherley’s The Country Wife, which gained a reputation in its time for being both bawdy and witty. We will begin with an introduction to the dramatist and the form and then proceed to a discussion of the play and its elements and conclude with a survey of the criticism it has garnered over the years. Section One: William Wycherley and the Comedy of Manners William Wycherley (b.1640- d.1716) is considered one of the major Restoration playwrights. He wrote at a time when the monarchy in England had just been re-established with the crowning of Charles II in 1660. The newly crowned king effected a cultural restoration by reopening the theatres which had been shut since 1642. There was a proliferation of theatres and theatre-goers. A main reason for the last was the introduction of women actors. Puritan solemnity was replaced with general levity, a characteristic of the Caroline court. Restoration Comedy exemplifies an aristocratic albeit chauvinistic lifestyle of relentless sexual intrigue and conquest. The Comedy of Manners in particular, satirizes the pretentious morality and wit of the upper classes. -

John Milton's Pedagogical Philosophy As It Applies to His Prose and Poetry

JOHN MILTON'S PEDAGOGICAL PHILOSOPHY AS IT APPLIES TO HIS PROSE AND POETRY by JOOLY MARY VARGHESE, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved May, 1999 Copyright 1999 Jooly Mary Varghese, B.A., M.A ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work could not have been completed without the help of many dear friends and family members, and while unable to name all of them individually here, I am thankful to each one of them. I am immensely grateful to my committee chairperson, Dr. Thomas Langford, who initially gave me the idea for this work. I feel somewhat inept in my attempt to express my gratitude, for he has not only served as a chairperson, but as a mentor, an advisor, and an example of the kind of teacher I aspire to be like. I am also thankful to Dr. James Whitlark for his interest in my work and for his timely and helpful responses, and to Dr. Don Rude for his guidance and support. There are several friends in the department to whom I am grateful for their advice and friendship. Special thanks to Pat and especially to Robin for the many hours in the computer lab working on formatting and other such exciting matters. Robin, I think I still owe you a "fizzy drink." Thank you. 11 My greatest thanks are for my family, especially my parents, whose love and prayers, I am certain, are the reason for my success in this endeavor. -

The Universal Character, Cave Beck

Fiat Lingua! ! Title: The Universal Character ! Author: Cave Beck ! MS Date: 04-15-2012! ! FL Date: 05-01-2012 ! FL Number: FL-000008-00 ! Citation: Beck, Cave. 1657.The Universal Character (Andy Drummond, Transcription).FL-000008-00, Fiat Lingua, <http://fiatlingua.org>. Web. 01 May. 2012.! ! Copyright: PD 1657 Cave Beck. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ! NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.! ! " ! http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/ Transcription of the 1657 edition of Cave Beck’s “The Universal Character”. What’s this all about then? The idea of a “universal language”, a language that can be understood by all peoples of the Earth, has been with us for several centuries. There were two periods when the idea flourished – firstly, at the start of the European Enlightenment era, in the 17th century; and again towards the second half of the 19th century, when the Socialist and pacifist movements began to take root. The very first published attempt at producing a universal language was made by Francis Lodwick in 1652, when he published his “The Ground-work or Foundation Laid (or so intended) For the Framing of a New Perfect Language: and an Universall or Common Writing”. This was a very brief description of a universal language scheme, running to no more than 19 pages. But it heralded the beginning of a golden era of similar schemes, which culminated in – and arguably was finished off by – John Wilkins’ “Essay Towards a Universal Character” of 1668.