Technical Note No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental Use of a Weather Buoy in Wind

Reprint 893 Wind Data Collected by a Fixed-wing Aircraft in the Vicinity of a Typhoon over the South China Coastal Waters P.W. Chan & K.K. Hon The 29 th Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology, 10-14 May 2010, Tucson, Arizona, USA Wind data collected by a fixed-wing aircraft in the vicinity of a typhoon over the south China coastal waters P.W. Chan * and K.K. Hon Hong Kong Observatory, Hong Kong, China Abstract: east of Hong Kong, GFS conducted a SAR operation near the typhoon. The J41 aircraft equipped with The fixed-wing aircraft of Government Flying Service AIMMS-20 flied within 100 km from the centre of of the Hong Kong Government has recently equipped Molave. At that time, the horizontal wind and with an upgraded meteorological measuring system. pressure measurements from AIMMS20 were Besides search and rescue (SAR) missions, this checked to be normal. This SAR operation provided aircraft is also used for windshear and turbulence valuable observations about the typhoon that could investigation flights at the Hong Kong International not be achieved with the conventional meteorological Airport. In a SAR operation in July 2009, the aircraft measurements (including both in situ and remote flew close to the eye of Typhoon Molave, when it was sensing measurements) available in the region. In located at about 200 km to the east of Hong Kong particular, the 20-Hz wind data could be used to over the south China coastal waters. The aircraft calculate the wind spectrum and turbulence intensity provided valuable information about the winds in such as eddy dissipation rate (EDR) at various association with Molave. -

New HKETO Director to Promote Hong Kong in ASEAN Countries

HONG KONG ECONOMIC & TRADE OFFICE • SINGAPORE FilesFiles FEBRUARY 2002 ISSUE • MITA (P) 297/09/2001 New HKETO Director to promote Hong Kong in ASEAN countries THE Hong Kong Economic and Trade rule of law, a clean and accountable Office (HKETO) would strive to its administration, the free flow of captial, uttermost to maintain and foster the close information and ideas, a level playing tie between Hong Kong and ASEAN field would continue to provide the countries in trade, business and culture, basis of Hong Kong’s success in the Mr Rex Chang, Director of HKETO in future. While Hong Kong’s strategic Singapore, said at a welcoming reception location with China as its hinterland, in January. low and simple taxes, world- class Mr Chang said, “ ASEAN, taken as a transport and communication group, is Hong Kong’s third largest infrastructure, concentration of top market for domestic exports, re-exports flight financial and business service and source of imports. It is also the Mr Rex Chang, Director of Hong Kong Economic providers had all worked out to make fourth largest trading partner of Hong and Trade Office, addressing at the reception. Hong Kong the Asia’s World City. Kong. Five of the ASEAN countries, Over 200 guests including diplomats, namely Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, enhance the understanding of Hong government officials, senior business the Philippines and Indonesia, are Kong in the region. Mr Chang added that executives and representatives from the among the top 20 trading partners of Hong Kong welcomed more investment media and community organisations Hong Kong.” from the region. -

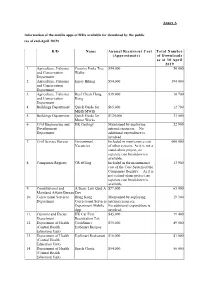

Information of the Mobile Apps of B/Ds Available for Download by the Public (As of End-April 2019)

Annex A Information of the mobile apps of B/Ds available for download by the public (as of end-April 2019) B/D Name Annual Recurrent Cost Total Number (Approximate) of Downloads as at 30 April 2019 1. Agriculture, Fisheries Country Parks Tree $54,000 50 000 and Conservation Walks Department 2. Agriculture, Fisheries Enjoy Hiking $54,000 394 000 and Conservation Department 3. Agriculture, Fisheries Reef Check Hong $39,000 10 700 and Conservation Kong Department 4. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $65,000 12 700 MBIS/MWIS 5. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $120,000 33 000 Minor Works 6. Civil Engineering and HK Geology Maintained by deploying 22 900 Development internal resources. No Department additional expenditure is involved. 7. Civil Service Bureau Government Included in maintenance cost 600 000 Vacancies of other systems. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 8. Companies Registry CR eFiling Included in the maintenance 13 900 cost of the Core System of the Companies Registry. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 9. Constitutional and A Basic Law Quiz A $77,000 65 000 Mainland Affairs Bureau Day 10. Correctional Services Hong Kong Maintained by deploying 19 300 Department Correctional Services internal resources. Department Mobile No additional expenditure is App involved. 11. Customs and Excise HK Car First $45,000 19 400 Department Registration Tax 12. Department of Health CookSmart: $35,000 49 000 (Central Health EatSmart Recipes Education Unit) 13. Department of Health EatSmart Restaurant $16,000 41 000 (Central Health Education Unit) 14. -

Astronomy Education in China, Hong Kong Or on This Document Please Contact the Office of Astronomy for Education ([email protected])

Astronomy Education in China, Hong Kong This overview is part of the project "Astronomy Education Worldwide" of the International Astronomical Union's Office of Astronomy for Education. More information: https://astro4edu.org/worldwide Structure of education: Usually, children start their learning in kindergartens from 3 to 6 years old. It is followed by 6-year formal education in mainstream primary education (taught in Chinese, English and Mandarin). Secondary school is compulsory for 6 years, studying all subjects for the first 3 years and registering their interested subjects (from Liberal Arts, Science and Business) as electives for the remaining 3 years. There would be Territory-wide System Assessments for P.3, P.6 and F.3 students every year for evaluating the overall learning standard of students. All twelve years of education at public schools are free of charge if studying at government and aided schools. In the final year of secondary studies, Form 6 Students need to prepare for the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education (HKDSE) Examination to fulfill requirements for higher-level studies. As for Post-secondary Education, there are multiple study pathways, such as 4-year bachelor’s degree programs and 2-year sub-degree programs. For non-Chinese speaking students and foreign nationals, there are also some international schools and private schools in primary and secondary education. They will continue their further studies to overseas universities or high-level educational colleges after another public examination, such as GCE A-Level and IB Diploma (different curriculum comparing to the mainstream education). Education facilities: Hong Kong schools have typical class sizes of around 25 to 30 students, students usually would have the same timetables from primary to secondary (P.1-P.6 and F.1-F.3). -

Windshear and Turbulence in Hong Kong

WWiinnddsshheeaarr aanndd TTuurrbbuulleennccee iinn HHoonngg KKoonngg - information for pilots Published by the Hong Kong Observatory, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. 1st edition ©2002 2nd edition ©2005 3rd edition ©2010 Copyright reserved 2010. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the Director of the Hong Kong Observatory. Disclaimer The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (including its servants and agents), the International Federation of Air Line Pilots’ Associations and The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators make no warranty, statement or representation, express or implied, with respect to the accuracy, availability, completeness or usefulness of the information, contained herein, and in so far as permitted by law, shall not have any legal liability or responsibility (including liability for negligence) for any loss or damage, which may result, whether directly or indirectly, from the supply or use of such information or in reliance thereon. Foreword The Hong Kong Observatory (HKO) provides windshear and turbulence alerting service for aircraft using the Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA). This booklet aims at providing pilots and air navigators with the basic information on windshear and turbulence, their causes, and the windshear and turbulence alerting service in Hong Kong. Compared with the last edition, the present edition has incorporated in particular the latest knowledge and experience with Published by the Hong Kong Observatory, Hong Kong Special the operation of LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging), a powerful Administrative Region Government. tool in warning windshear and turbulence under clear-air conditions. Other updated items include: aircraft flight data and 1st edition ©2002 some analyses in connection with “gentle windshear”. -

Harrow Hong Kong's Severe Weather Policy

Harrow International School Hong Kong: Severe Weather Procedures The rainy season in Hong Kong usually runs from April to September and in severe weather conditions, the School adheres to official public announcements from the Hong Kong Observatory and the Education Bureau. Broadcasts are usually announced on both radio and television by 6.15am and are repeated at regular and frequent intervals throughout the day. Parents are advised to take note of the following arrangements, which apply in all cases except when pupils are taking external examinations (see External Examinations below). Procedures when a signal is raised before School starts: Typhoon 1 All Early Years to Y13 classes will operate as usual. Typhoon 3 Early Years will close. Y1 to Y13 classes operate as usual unless otherwise instructed Pre-Typhoon 8 Lessons will be stopped for the entire day for all pupils and boarders will be /Typhoon 8 or supervised by onsite staff. above # Amber Rainstorm All Early Years to Y13 classes will operate as usual. Red Rainstorm # Lessons will be stopped for the entire day for all pupils and boarders will be supervised by onsite staff Black Rainstorm # Lessons will be stopped for the entire day for all pupils and boarders will be supervised by onsite staff # If a signal is raised while pupils are travelling to School, the School will be responsible for their supervision until it is safe for them to return home or until a parent or carer collects them from School. Pupils who have not left for School should stay at home. Please note that formal lessons will not be conducted, even if some pupils do come to School. -

Hong Kong 2007

100 Chapter 5 Commerce and Industry As a place for doing business, Hong Kong is hard to beat. It has all the advantages for trade to flourish: low tax rates, modern infrastructure, rule of law, free flow of capital and information and, equally important, it is the world’s freest economy and gateway to today’s most sought-after market — the mainland of China. Hong Kong is a leading international trading and services hub as well as a high value-added manufacturing base. It is widely recognised as one of the freest economies in the world, and the gateway to the Mainland market. Hong Kong’s continuing economic success owes much to a simple tax structure and low tax rates, a versatile and industrious workforce, excellent infrastructure, free flow of capital and information, the rule of law, and the Government’s firm commitment to free trade and free enterprise. The Government sees its task as facilitating commerce and industry within the framework of a free market. It does not impose tariffs. Regulatory measures on international trade are kept to a minimum. Hong Kong also adopts an open and liberal investment policy and actively encourages inward investment. The Government’s industrial policy is designed to promote industrial development by creating a business-friendly environment and providing adequate support services and infrastructure. It promotes innovation and technological improvement to match Hong Kong industry’s shift towards knowledge-based and high value-added activities. It aims to strengthen support for technology development and application, promote the wider use of design, develop a critical mass of fine scientists, engineers and designers, skilled technicians and venture capitalists, and encourage the development of a significant cluster of innovation and technology- based businesses. -

Hong Kong Observatory 2018

` Hong Kong Observatory 2018 INTRODUCTION The highest temperature recorded at the Observatory in the year was 35.4 degrees on 30 May, the eleventh highest since records began in 1884. The three main objectives of the Hong Kong There were 26 Hot Nights and 36 Very Hot Days in Observatory (the Observatory) are: Hong Kong in 2018, ranking the eighth highest and the third highest on record respectively. For low (1) to provide weather forecasts and warnings temperatures, the number of Cold Days in the year to meet the public’s demand for weather was 21 days, which is 3.9 days more than the 1981- services, and to provide weather services 2010 normal. The lowest temperature recorded at for aviation and shipping in accordance the Observatory in the year was 6.8 degrees on 1 with international standards; February. (2) to monitor local environmental radiation levels and impacts, and to advise the Government on counter-measures that may be necessary during nuclear emergencies; (3) to maintain the Hong Kong time standard and to provide geophysical, oceanographic, astronomical and climatological information and consultative services to the public and business sectors. During the financial year 2018-19, the department’s total expenditure was $338.2 million Monthly mean temperature anomalies in Hong Kong in 2018 and the total revenue was $123.2 million. By the end of the financial year, there were altogether 311 civil Six tropical cyclones affected Hong Kong in the servants, 20 non-civil service contract staff and 28 T- year. Among them, Tropical Cyclone Mangkhut contract staff working in the department. -

Chi Ming Shun, Hong Kong Observatory

8.3 IMPLEMENTATION OF A DOPPLER LIGHT DETECTION AND RANGING (LIDAR) SYSTEM FOR THE HONG KONG INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Chi Ming Shun* and S.Y. Lau Hong Kong Observatory, Hong Kong 1. INTRODUCTION corridors relative to this terrain. The ENE-WSW oriented island has a width of about 5 km and length Hong Kong is implementing a Doppler LIght of about 20 km. In the middle of Lantau, a U-shape Detection And Ranging (LIDAR) System at the Hong ridge with peaks rising to between 750 and 950 m Kong International Airport (HKIA) to supplement the above mean sea level (amsl) and mountain passes Terminal Doppler Weather Radar (TDWR) in the as low as 350 to 450 m amsl separating these peaks. detection and warning of low-level wind shear under To the southwest of this U-shape ridge, an clear-air conditions. ENE-WSW oriented ridge rises to between 400 and 500 m amsl at many locations along the ridgeline. Installed in 1996, the TDWR has proved to be effective in the detection and warning of low-level A TDWR was installed at Tai Lam Chung at wind shear in rainy weather. However, reports of about 12 km northeast of the airport (see Figure 1 wind shear received from aircraft pilots landing at or for location of the TDWR) for detecting microburst taking off from the new HKIA since its opening in and wind shear associated with convective storms 1998 indicate that it is possible for low-level wind (Shun and Johnson 1995). A network of shear to also occur in clear-air conditions, under ground-based anemometers over and in the vicinity of which TDWR return signals are not always available. -

Hong Kong Weather Services for Shipping

HONG KONG WEATHER SERVICES FOR SHIPPING 16th EDITION 2007 Hong Kong © Copyright reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the Director of the Hong Kong Observatory. NOTES: The Hong Kong Observatory is located at latitude 22°18’N and longitude 114°10’E. Since 1 January 1972, the Hong Kong Time Service has been based on Co-ordinated Universal Time (UTC). The Hong Kong Time (HKT) is 8 hours ahead of UTC and for most practical purposes, UTC can be taken to be the same as Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Since 1 January 1986, the Hong Kong Observatory has adopted metric units in the provision of weather services to the public. This includes the use of ‘kilometres’ (km) for measurement of horizontal distance and ‘kilometres per hour’ (km/h) for measurement of wind speed and speed of movement of weather systems. However, the units ‘knots’ and ‘nautical miles’ remain to be used in weather bulletins and warnings for international shipping. For ease of reference, wind speeds in knots and metric units corresponding to each category of the Beaufort scale of wind force adopted by the Hong Kong Observatory are given in Appendix I. The information given in this publication is also available on the Hong Kong Observatory website: http://www.hko.gov.hk/wservice/tsheet/pms/index_e.htm CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 WEATHER SERVICES FOR SHIPS IN THE CHINA SEAS AND THE WESTERN NORTH PACIFIC 5 2.1 Meteorological Messages for the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System 5 2.2 Marine Weather Forecasts 6 2.3 Weather Information -

Speech by Dr CHENG Cho-Ming, Director of the Hong Kong Observatory 23 March 2021

Speech by Dr CHENG Cho-ming, Director of the Hong Kong Observatory 23 March 2021 Very happy to meet all of you again at this annual press briefing. Before reporting on the latest developments in the Hong Kong Observatory, let me first introduce my fellow Assistant Directors. They are: 1. Miss LAU Sum-yee, responsible for aviation weather services, 2. Mr CHAN Pak-wai, responsible for public weather services, 3. Mr LEE Lap-shun, responsible for radiation monitoring and instruments, and 4. Ms SONG Man-kuen, Acting Assistant Director responsible for climate and geophysical services. Today, 23 March, is not only the day of the Observatory’s annual press briefing, but also the World Meteorological Day, with the theme “The Ocean, our climate and weather”. It aims to remind us that climate and weather are closely related to the ocean apart from the atmosphere. Talking about the ocean, one may think of the La Nina phenomenon. With the development of La Niña in the latter part of 2020, intense cold surges advanced southwards in late 2020, bringing cold weather to southern China. However, the World Meteorological Organization's preliminary assessment indicated that year 2020 was still one of the three warmest years on record globally. The decade 2011-2020 was also the warmest on record. In 2020, various extreme weather events continued to affect different parts of the world, including the record high temperature of 38°C in the Arctic Siberian town of Verkhoyansk; severe flooding triggered by extreme rainfall in South Asia, China, Korean Peninsula, Viet Nam and parts of western Japan; and destructive wildfires exacerbated by high temperatures in California and Colorado of the United States, northern Siberia, eastern Australia, and western Brazil. -

3. Conduct of Performance Review of the Windshear and 3 Turbulence Alerting Service

HONG KONG OBSERVATORY Technical Note No. 102 WINDSHEAR AND TURBULENCE ALERTING SERVICE AT THE HONG KONG INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT − A REVIEW by S.Y. Lau, C.M. Shun and B.Y. Lee © Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government Published March 2002 Prepared by Hong Kong Observatory 134A Nathan Road Kowloon Hong Kong This publication is prepared and disseminated in the interest of promoting information exchange. The findings, conclusions and views contained herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Hong Kong Observatory or the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (including its servants and agents) makes no warranty, statement or representation, express or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the information contained herein, and in so far as permitted by law, shall not have any legal liability or responsibility (including liability for negligence) for any loss, damage, or injury (including death) which may result, whether directly or indirectly, from the supply or use of such information. Mention of product of manufacturer does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement or recommendation. Permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be obtained through the Hong Kong Observatory. 551.557.4:551.551(512.317) CONTENTS Page Abstract iii Figures iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Background 2 3. Conduct of performance review of the windshear and 3 turbulence alerting service 4. Findings of the review 4 5. Common weather patterns for windshear and turbulence at the 6 Hong Kong International Airport 6. Improvement work and achievements 9 7.